Courts-martial of the United States 🇺🇸

૯ᑯɪ੮૦ʀɪɑʟ ઽ੮ɑ⨍⨍United States military courts are trials conducted by the U.S. military or state military. Military field courts are most often convened to try U.S. military personnel for criminal violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), which is the criminal code of the U.S. armed forces. However, they may also be convened for other purposes, including military tribunals and the observance of martial law in the occupied territory. Federal military field courts are governed by the rules of procedure and evidence set out in the Manual for Military Field Courts, which contains the Rules for Military Field Courts, the Military Rules of Evidence, and other instructions. The state military field courts shall be governed by the laws of the state concerned. The American Bar Association has issued a model of the State Code of Military Justice, which has influenced relevant laws and procedures in some states. Military field courts are adversarial trials, as are all criminal courts in the United States. That is, lawyers representing the Government and the accused present the facts, legal aspects and arguments most favorable to each party; a military judge decides questions of law, and members of the collegium (or a military judge in the case of a sole judge) decide on the fact. The State National Guard (Air Force and Army) may convene summary and special military courts to hear peacetime war crimes committed by non-federalized Guards pilots and soldiers, as well as federal military courts. The State National Guard's right to convene military tribunals is under Title 32 of the U.S. Code. In states where there is an armed force (state guard) that is not part of the National Guard, regulated by the federal government, military courts are convened on the basis of state laws. From the earliest days of the United States, military command played a central role in the administration of military justice. The American military justice system, inherited from its British predecessor, predates the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution. While military justice in the United States has undergone significant changes over the years, the convening body remains a tool for selecting a panel for military field courts. Tribunals for the trial of war criminals coexisted with the early history of armies. Modern military field courts are deeply rooted in systems that preceded written military codes and were designed to bring order and discipline to the armed, and sometimes barbaric, warring forces. Both the ancient Greeks and Romans had codes of military justice, although their written versions have not survived. Moreover, almost every form of military tribunal involved a trial before a group or members of one type or another .U.S.

The concept of an American military tribunal was derived from the Court of Knights in England and the military code of the Swedish king Gustav Adolf. Both of these courts sought to strike a balance between the requirements of due process and discipline and the concept of due process. This, in turn, laid the groundwork for modern military justice systems that seek the same. The Knight's Court had a direct impact on British articles about the war. Early British articles on the war reflected concerns about due process and the composition of the commission's members. When war broke out between the American colonists and the British in 1775, the British acted in accordance with the 1765 edition of the Articles of War. This version will serve as a model for military justice in the Continental Army. When the United States declared independence and fought the War of Independence, "it had a ready-made military justice system." Despite the colonists' dissatisfaction with the British, they still recognized the intrinsic value of the British military justice system in ensuring good order and discipline in their own armed forces.

- William Sids Military Court, 1778

British articles on the War of 1765 were a model for the American military justice system. Accordingly, the general panel of the military tribunal consisted of thirteen officers selected by the convening body, with a field-level officer as president. The regimental tribunal consisted of five officers selected by the regimental commander; however, unlike the British equivalent, the regimental commander could not sit as president. In addition, the Continental Congress broke away from the British system in an even more significant way: the American articles on war were created by a legislative decree, not an executive order. Thus, in the American system, the legislature took over the management of the armed forces from the very beginning - military justice was not to be transferred to the executive. Second, Congress has demonstrated its flexibility and willingness to modify articles as needed. Chief military lawyer Colonel William Tudor told Congress that the articles needed improvement. Congress will continue to revise articles several times to reflect the realities of small armed forces. Nevertheless, the commander retained his role in the administration of justice. Until 1916, a soldier accused in a general military tribunal had no right to a lawyer. However, a soldier may request a lawyer or pay for it. Prior to 1916, a judge-lawyer had a triple duty. To prosecute the case, to ensure the protection of the rights of the accused soldier or sailor, including to ensure the presence of witnesses favorable to the accused, and to inform the military tribunal according to the law. Until 1969, there was no military judge to protect the rights of the accused to due process. According to University of New Mexico Law School professor Joshua E. Castenberg, there were aspects of the military tribunal that outperformed the state's criminal courts in terms of proper legal protection, but there were widespread violations of due process that forced Congress to review military field courts in 1920 and 1945-50, respectively. After World War II, concerns among veteran organizations and bar associations about the military justice system in general, and in particular the problems of the illegal command influence of military field courts, led to substantial congressional reform. The Eighty-first Congress (1949–51) decided to create a unified military justice system for all federal military services and appointed a committee chaired by Harvard Law University professor Edmund Morgan to study military justice and draft related legislation. According to Professor Morgan, the task was to draft a law that would ensure the full protection of human rights without violating military discipline or military functions. This would mean "a complete rejection of the military justice system, conceived only as a management tool," but would also negate "a system designed to be applied, since criminal law is exercised in a civilian criminal court." The result was the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), a code that ensured due process for military personnel while maintaining command control over the appointment of members of a military tribunal.

Congressional Follow-up on UCMJ The next time Congress held a formal hearing on the UCMJ was when it passed the Military Justice Act of 1983. In 1999, Congress required the Secretary of Defense to examine the selection of members of the commission by the command. Congress took no action when the Joint Services Committee (AO) concluded that "the current system is likely to get better members within the operational constraints of the military justice system." In 2001, the Commission for the Celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Uniform Code of Military Justice disagreed with the 1999 report of the CJSC, noting that "there is no aspect of military criminal proceedings that differs from civilian practice or gives a greater impression of improper influence than the outdated panel selection process." Loading... Constitutional basis for military-federal courts The drafters of the Constitution were aware of the power struggle between Parliament and the King regarding the powers of the armed forces. Many of the Founders were combat veterans from the Continental Army and understood the demands of military life and the need for a well-disciplined fighting force. The decision of the government of the armed forces was a classic balance of constitutional interests and powers. They assured that Congress – with its responsiveness to the population, its fact-finding ability and its collective deliberation processes – would ensure the management of the armed forces. The drafting of the Constitution had great respect for the separation of powers. One of the main purposes of the Constitutional Convention in correcting the shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation was to create a government in which the individual branches of government served to restrain and balance each other. The principles of separation of powers also apply to the military. The founders gave power to the executive and legislative branches of government, but left the judiciary with only a secondary role in the management of the armed forces. By distributing power over the armed forces between the legislative and executive branches of government, the founders "avoided much of the military-political power struggle that is so characteristic of the early history of the British system of military field courts." Moreover, the developers explained that, although the command of the armed forces is in the hands of the executive branch, the management and regulation of the armed forces will be carried out in accordance with the law adopted by the legislature. Consequently, the government of the armed forces will always reflect the will of the people, expressed through its representatives in Congress. After ratifying the Constitution in 1789, the First Congress enacted legislative measures to ensure government and regulate the armed forces of the United States. On September 29, 1789, Congress explicitly passed the Articles of War currently in force for the Continental Army. Thus, it can be said that Congress continued the work of the military tribunal, as it was established earlier, and "the military tribunal is in fact considered to be older than the Constitution and therefore older than any court of the United States established or authorized by this document. " The First Congress and the founders were also aware of the age and history of the military tribunal involving the commander, as well as the customs and traditions associated with it. In 1969, the Supreme Court in O'Callahan v. Parker stripped the military of much of the jurisdiction that Congress had granted to the UCMJ. By 1987, however, the Supreme Court had changed course and recognized that prior to 1950, federal courts operated on the basis of a strict habeas test, where the court often considered a single question: whether the military had personal jurisdiction over a soldier or sailor under investigation. That is, the courts did not check whether the military complied with due process. Beginning in the 1950s, federal courts gradually accepted appeals based on claims for denial of due process.

Types of military field courts

Colonel Billy Mitchell during his military tribunal in 1925.

Federal Military Tribunal of the Civil War era after the Battle of Gettysburg.

There are three types of federal military courts: total, special, and general. A conviction in a general military tribunal is equivalent to a conviction for a civil criminal offense in federal district or state criminal court. Special military field courts are considered "federal misdemeanors" akin to the misdemeanor of state courts, since they cannot impose a lien for more than one year. Military field courts of general jurisdiction have no civilian equivalent, except perhaps not in criminal proceedings, since the U.S. Supreme Court has declared them administrative in nature, since there is no right to a lawyer; although, as a benefit, the Air Force provides such pilots with such a charge. Military personnel must consent to a trial by a military tribunal, and military personnel cannot be tried in such proceedings. A summary conviction of a court is equivalent by law to proceedings under article 15. The Military Field Court Trial by a Military Summary Tribunal provides a simple procedure for dealing with allegations of relatively minor misconduct committed by members of the armed forces. Officers cannot be brought before a military summary court. The listed accused must consent to be tried by a military summary tribunal, and if consent is not granted, the command may set aside the charge by other means, including an indication that the case be tried before a special or general military tribunal. The Military Summary Tribunal consists of one person who is not a military prosecutor, but still serves as a judge and single-handedly establishes the facts. The maximum penalty in a summary military tribunal depends on the salary level of the accused. If the accused has an E-4 salary level or lower, he may be sentenced to 30 days in prison, demotion to E-1 or a limit of 60 days. Penalties for servicemen with salary grades E-5 and above (e.g., Sergeant in the Army or Marine Corps, Petty Officer 2nd Class in the Navy or Coast Guard) are similar, except that they can be reduced by only one category of salary and cannot be limited. The accused before the military tribunal of summary proceedings shall not have the right to legal representation of the military defence counsel. However, while not required by law, some services, such as the U.S. Air Force, provide defendants at trial with free military attorneys for a simplified military tribunal in accordance with policy. If the Government decides not to provide the accused with a free military lawyer, that person may hire a civilian lawyer to represent him at his own expense.

The Special Military Court is a court of intermediate instance. It consists of a military judge, a defence counsel (prosecutor), a defence counsel and at least three officers sitting on the court(s). A military judge may appoint a military magistrate to conduct the trial. An ordinary accused may apply for the establishment of a court composed of at least one third of the rank-and-file. Instead, the ad hoc military tribunal may consist of one judge if so required by the accused or the convening body so decides. An accused in a special military tribunal has the right to free legal representation of a military lawyer and may also hire a civilian lawyer at his own expense. Regardless of the offences in question, the special sentence of a military tribunal is limited to deprivation of more than two thirds of the basic salary per month for one year and for ordinary personnel to one year of imprisonment (or a smaller amount if the offences are punishable by deprivation of liberty). lower maximum), and / or the category of unfair behavior; if the trial is conducted only by a military judge, the sentence shall be reduced to a maximum term of imprisonment of six months and/or deprivation of wages for more than six months, and dismissal from office shall not be permitted. General Military Field Court Military Tribunal is the highest court. It is composed of a military judge, a defence counsel (prosecutor), a defence counsel and at least five officers sitting on a panel of a military tribunal. An ordinary accused may apply for the establishment of a court composed of at least one third of the rank-and-file. The accused may also request a trial only by a judge. In the General Military Tribunal, the maximum penalty is set for each offence in accordance with the Guidelines for Military Field Courts (MCM) and may include death for certain offences, imprisonment, dismissal for dishonest or bad conduct for military personnel, dismissal for officers or a number of other forms of punishment. The Military Tribunal is the only court that can pass the death penalty. Before the case is referred to the General Military Court, a pre-trial investigation must be conducted in accordance with article 32 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, unless the accused relinquies from it; it's the equivalent of a grand jury civil trial. The accused in the general military tribunal has the right to free legal representation of a military lawyer, and can also hire a civilian lawyer at his own expense.

Military Court Pre-trial Detention Under Article 10 of the UCMJ, "immediate steps" must be taken to bring the accused to trial. Although there is currently no ceiling on pre-trial detention, Rule 707 of the Military Field Court Manual prescribes a total maximum of 120 days for "expedited trial". According to article 13, punishment other than arrest or imprisonment is prohibited until trial, and imprisonment shall not be more severe than is required to ensure the presence of the accused in court. In UCMJ language, "arrest" refers to the physical limitation of certain geographic boundaries. "Detention" in U.S. military law is what is commonly referred to as arrest in most legal systems. Composition of courts According to Article 25 of the UCMJ, the members of the court are elected from among the military by the convening body. Although the founding fathers of the United States guaranteed American citizens the right to a jury trial in both the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, they decided that Congress would establish rules for disciplinary action against the armed forces. From the outset, Congress has maintained the long-standing practice that, contrary to the principle of random jury selection, the convening body personally selects the members of the military tribunal panel. Whether such practices contribute to a fair process is the subject of critical investigation. The Military Tribunal has always been a special tribunal established and appointed by order of the Commander as the convening body. The Tribunal was set up specifically to deal with a number of allegations that the commander has referred to the court. The convening body reviews the legislative prescriptions of the United States Congress, which are "most qualified," when choosing a "panel" or jury for a military tribunal. In turn, the members of the military tribunal, who are normally under the command of the convening body, take an oath "to judge in good faith and impartially, in accordance with the evidence, their conscience and the laws applicable to the court by a military tribunal". , the case of the accused. " By their oath, the members of the commission expressly agree to renounce any influence on the part of the commander who appointed them. In cases where the accused is an enlisted member, the accused may request that enlisted military personnel be appointed to the commission. A defence counsel appointed or hired may challenge both the military judge and the members of the panel for a good reason. However, a military judge shall determine the relevance and validity of any objection. The prosecution and the defence initially have one peremptory challenge to the members of the military tribunal. The accused may also challenge a member of the panel in the case "at any other time during the trial when it becomes apparent that there are grounds for recusal". The UCMJ prohibits the convening body from exerting unlawful influence on the court. A lawyer may file a motion challenging the legality of a military tribunal if it appears that the convening body has unlawfully influenced the members of the military tribunal. Burden of proof At the trial of a military tribunal, the accused soldier is considered innocent. Meanwhile, the Government bears the burden of proving the guilt of the accused with lawful and competent evidence in the absence of reasonable doubt. Reasonable doubt as to the guilt of the accused must be resolved in favour of the accused. In other words, the accused soldier must be "without doubt"; or, more simply, there should be no reasonable chance or probability - according to the evidence and trials - of the innocence of the accused. If the accused is accused of an offence punishable by death, the conviction on this allegation requires all members of the military tribunal to vote for the "guilty". Otherwise, all other offences require a two-thirds majority of the members of the military tribunal to vote "guilty" for sentencing. If an accused soldier chooses to be tried by a military judge sitting alone rather than in a panel of a military tribunal, then a military judge will determine the guilt. Sentencing in court proceedings is carried out by the same court that found guilty. In other words, if an accused soldier decides that members of a military tribunal determine his or her guilt, those same members of the military tribunal shall render the sentence after the conviction is pronounced. If the accused soldier decides that he will be tried by one military judge, that military judge (alone) will sentence the accused (if the verdict is handed down as a result of such a trial). The death penalty requires a military tribunal; and, further, all members must unanimously agree to the proposal. A sentence of imprisonment for more than ten years may be imposed by a military judge sitting alone or, if the accused decides to be tried by members, with the consent of three-fourths of the members of the military tribunal. Any lesser sentence may be pronounced at trial by a military judge sitting alone or, if the accused decides to be tried by members, with the consent of two thirds of the members of the military tribunal.

Appeals In each case, there are procedures for consideration after trial, although the scope of these rights of appeal depends on the punishment imposed by the court and approved by the convening body. Cases involving punitive release, dismissal, imprisonment for a term of one year or more or death will be automatically tried by the relevant military criminal appeal court. Further consideration is possible in the Court of Appeal of the Armed Forces. Review of the powers of convocation In each case resulting in a conviction, the convening body (usually the same commander who ordered the trial to proceed and selected the members of the military tribunal) must review the case and decide whether the findings and sentence should be approved. Until June 24, 2014, the federal law provided that the right of the convening body to change the decision or sentence in favor of the convicted soldier was the prerogative of the command and was final. After June 24, 2014, the right of the convening body to release the convicted serviceman was significantly limited. After 24 June 2014, convocation bodies may not reject or reduce a conviction to one for a less serious offence, unless the maximum possible penalty of deprivation of liberty specified for the offence in the Manual for Military Field Courts is two years or less, and the sentence actually imposed has not been justified. not include dismissal, early dismissal, dismissal for bad behavior or imprisonment for more than six months. In addition, the convening body may not reject or reduce a conviction for rape, sexual violence, rape or sexual abuse of a child or forced sodomy, regardless of the sentence actually handed down in court. In addition, after June 24, 2014, the convening bodies may not reject, commush or suspend the sentence imposed, in whole or in part, the sentence imposed, which must be overturned, unjustifiably executed, dismissed for bad behavior or serve a sentence of more than six years. months of imprisonment. Exceptions to this limitation on the right to mitigate these types of punishment exist in cases where the convicted soldier enters into a pre-trial plea agreement in exchange for the reduction of any person found to be dishonest dismissal before dismissal for bad conduct, or where the convicted soldier provides "substantial assistance" to the investigation or prosecution of another person.

Criminal Appeal Courts After the conviction has been reviewed by the convening body, if the sentence includes death, dismissal, dismissal for lack of dignity, dismissal for misconduct or imprisonment for a year or more, the case is heard by the criminal appeal court of the relevant service. In cases where the sentence is not severe enough, there is no right to appeal the review. Four Serving Criminal Appeals Courts: Army Criminal Court of Appeal Marine Corps Criminal Court of Appeal U.S. Air Force Criminal Court of Appeal Criminal Court Coast Guard Criminal Appeals Courts criminal courts have the power to overturn convictions that are legally or factually inadequate and commut sentences they deem unreasonably harsh. The right to determine factual sufficiency is a unique right enjoyed by the Court of Appeal, and in exercising this power, criminal appeals courts can separately weigh evidence, assess the credibility of witnesses and decide disputed questions of fact, even if only the Court of First Instance has seen and heard witnesses. The accused will be assigned a defence counsel on appeal, who will represent him free of charge on appeal. A civil lawyer may be hired at the expense of the accused. In the Court of Criminal Appeals, a soldier sentenced to death, dismissal, dishonest dismissal, dismissal for misconduct or imprisonment for more than a year may also petition the United States' highest military court, the Court of Appeal for the Armed Forces (CAAF). This court consists of 5 civil judges appointed for fifteen-year terms, and it can correct any legal error it may find. The appellate counsel will also be available for free assistance to the accused. Again, the accused may also be represented by a civil lawyer, but at his or her own expense. The CAAF audit is discretionary and a limited number of cases are handled each year. For the fiscal year beginning October 1, 2012 and ending September 30, 2013, CAAF received a total of 964 applications and reviewed 900 cases. Of these 900 cases, 39 were closed on the basis of signed or individual opinions and 861 on the basis of memorandums or orders. As a last resort, a convicted soldier may also apply to the President of the United States for a stay or pardon under constitutional authority.

Military field and appellate courts as legislative.

Federal courts have historically been reluctant to grant appeals to military field courts. In dynes v. Hoover, the 1857 decision, the Supreme Court held that the criterion for determining whether an Article III court had constitutional power to hear a military tribunal's appeal on the merits was based on the sole question of whether the court had military jurisdiction over the person prosecuted in it. As a result, the Army or Navy could deviate from its war crimes to the detriment of the soldier. Thus, unless the Army, Navy, or President decides that a military tribunal was held by mistake, the soldier has received no assistance. Castenberg pointed out that the court issued Dynes' judgment almost simultaneously with Dred Scott v. Sanford, and there is a correlation between the two decisions. The court apparently agreed with the arguments of United States attorney Ransom Hooker Gillette that the discipline of the army in Kansas was in question because several officers found it terrible that they might have to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. (Gillet later became a bear cub during the Civil War and accused President Abraham Lincoln of being a tyrant.) While one of the goals of the government's argument at Dynes was voiced by the Civil War, it remained the Law on Military Field Courts until 1940. It is important to consider the appeal of the military tribunal in the Federal Court as a legislative court (article I). Article III courts do not deal with all court cases in the United States. Congress used its powers enumerated in the Constitution, combined with a necessary and appropriate article, to establish specialized tribunals, including military field courts. Section 8 of Article I of the Constitution states that Congress has the power to "set rules for government and the regulation of land and naval forces." Even when life and liberty are at stake, the legislative courts are not obliged to grant all the rights inherent in the courts under Article III. Of all the legislative courts established by Congress, military field courts received the most respect from Article III courts. Article III courts will not annul the balance reached by Congress with respect to the administration of military justice, unless the "fundamental right" concerned is "extremely important." Today's system of military field courts, including command selection of juries, lack of unanimity in verdicts, and admission to a panel of 3 or 5 members, still stands under scrutiny. This may be due to the fact that the accused in a trial before a general or special military tribunal enjoys significant legal rights to due process:

1. assistance of a lawyer;

2. information about the charges, including the possibility of obtaining detailed information;

3. Quick test;

4. mandatory process of interrogation of witnesses and evidence;

5. the right not to testify against oneself;

6. appeal in cases where the sentence is sufficiently severe.

Given these legitimate rights, the balance reached by Congress in the administration of justice would not be slightly disturbed by the Article III court.

Access to the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal Additional information:

Equal Justice Legislation for U.S. Military Personnel Under certain limited circumstances, military personnel are heard in the Supreme Court. Since 2005, various bills have been introduced in Congress to allow military personnel to appeal their cases to the U.S. Supreme Court. None of these bills have been passed, and as of 2010 it has not yet been passed.

See also Non-Judicial Punishment Recommendations Manual for Military Field Courts (MCM), USA (2008 edition) Further Reading Macomb, Alexander, Major General of the United States Army, Practice of Military Courts, (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1841) 154 pages. Macomb, Alexander, Treatise on Martial Law and Military Field Courts.

(Charleston: J. Hoff, 1809), reprinted (New York: Lawbook Exchange, June 2007), ISBN 1-58477-709-5, ISBN 978-1-58477-709-0 Oregon Model State Code of Military Justice Salzburg, Stephen; Schinasi, Lee D; And Schluster, David A., Guide to Military Rules of Evidence.

(Newark: LexisNexis, January 2003). ISBN 0-87215-969-8 ; ISBN 978-0-327-16329-9

U.S. Naval Courts 🇺🇸

https://telegra.ph/Preparation-for-the-International-Tribunal-07-13

Editorial recommendations for reading below ⬇️

https://telegra.ph/Preparation-for-the-International-Tribunal-07-13

https://telegra.ph/Secrets-of-the-failed-Emperor--of-the-World-07-17

https://telegra.ph/PATENT-A-PERSON-07-18

https://telegra.ph/A-monstrous-plan-in-the-final-stage-of-the-special-operation-07-18

https://telegra.ph/The-Lockstep-plan-and-the-artificial-disruption-of-supply-chains-07-07

https://telegra.ph/Hour-Y-07-19

https://telegra.ph/Red-Brown-fa%C3%A7ade-and-criminal-roof-of-the-house-07-20

https://telegra.ph/WEF-Private-property-and-privacy-will-disappear-by-2030-07-21

https://telegra.ph/Vaccinations-as-a-means-of-breeding-submissive-breeds-of-people-07-22

https://telegra.ph/DEMOCRACY-WITH-A-SOUL-OF-MAFIA-07-22

https://telegra.ph/Special-Operation-Pandemic-19-07-23

https://telegra.ph/MASS-MURDER-07-23

https://telegra.ph/Vaccination-2021-and-the-Nuremberg-Code-of-1947-07-23

https://telegra.ph/Battle-of-Ideas-07-24

https://telegra.ph/The-Rockefellers-outplayed-the-Rothschilds-on-the-Soviet-07-25

https://telegra.ph/AGENTS-OF-THE-NEW-COMMUNIST-CRIMINAL-ORDER-2021-07-27

https://telegra.ph/OPERATION-CORONATION-AND-OTHER-ADVENTURES-OF-MONICA-07-29

https://telegra.ph/FAILED-WORLD-CRIMINAL-COMMUNIST---FASCIST-REVOLUTION-07-30

https://telegra.ph/Terrorism-and-Communism-class-mathematics-and-the-voice-of-the-proletariat-07-30

https://telegra.ph/Operation-Paper-clip-08-01

https://telegra.ph/Agenda-21---a-plan-to-build-a-planetary-dystopia-08-01

https://telegra.ph/FIND-AND-NEUTRALIZE-IMMEDIATELY-082021-08-03

https://telegra.ph/GOATS--19-08-04

https://telegra.ph/FREEMASONS-SIGNS-SYMBOLS-LODGES-LAWS-FACES-08-05

https://telegra.ph/American-Lenin-is-not-Ulyanov-Forensic-examination-USA--USSR20-08-06

https://telegra.ph/INTERNATIONAL-CRIMINAL-GROUP-OF-STATE-BIOLOGICAL-TERRORISTS-2021-08-06

https://telegra.ph/The-Rockefeller-Plan-Lock-Step-and-the-Crown-of-08-07

https://telegra.ph/IN-THE-FOOTSTEPS-of--STATE-BIOLOGICAL-TERRORISTS-08-08

https://telegra.ph/GLOBAL-ISOLATION-IS-PROJECTED-FOR-2008-08-08

https://telegra.ph/STATE-BIOTERRORISM-CROWN-08-09

https://telegra.ph/STATE-BIOTERRORISM-CROWN-08-09

https://telegra.ph/PRODUCER--BORYA-08-09

🏴 BBC headquarter today (Twitter)

https://t.me/Tribulelouis/7222

Article in English and German

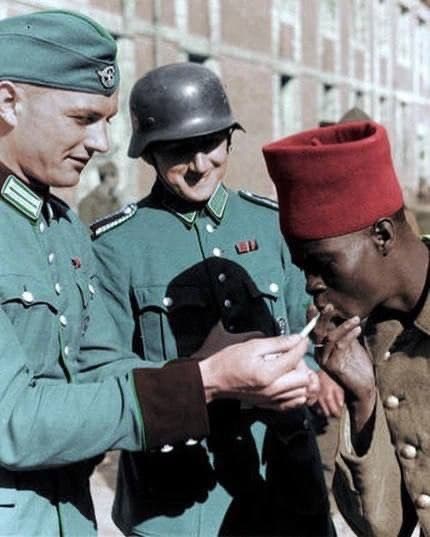

Two police officers (Ordnungspolizei) light a soldier of the French colonial troops, 1940

Ϻɾ. 𑀝ʝɠαɾ Χ