Nobel Prizes in Physics 2024

Truth about VaccinesIn our 2024 Nobel series: Physics, Physiology or Medicine, Chemistry, Peace Prize

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to John Hopfield of Princeton University and Geoffrey Hinton of the University of Toronto. Their groundbreaking research has transformed our understanding of neural networks and artificial intelligence, while also deepening our insight into how the human brain works.

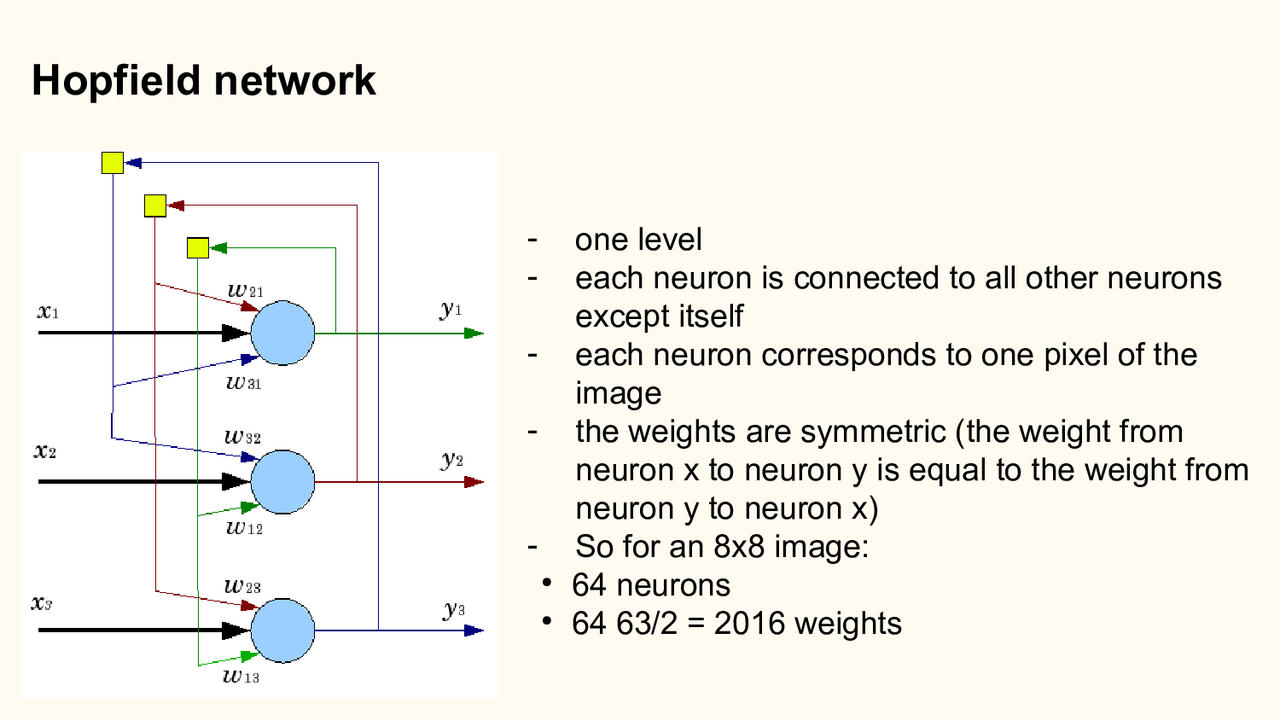

John Hopfield gained recognition for his 1982 work introducing a new model of neural networks – now known as the Hopfield network. This model revolutionized the way scientists think about associative memory. The Hopfield network is remarkably effective at storing and recalling information.

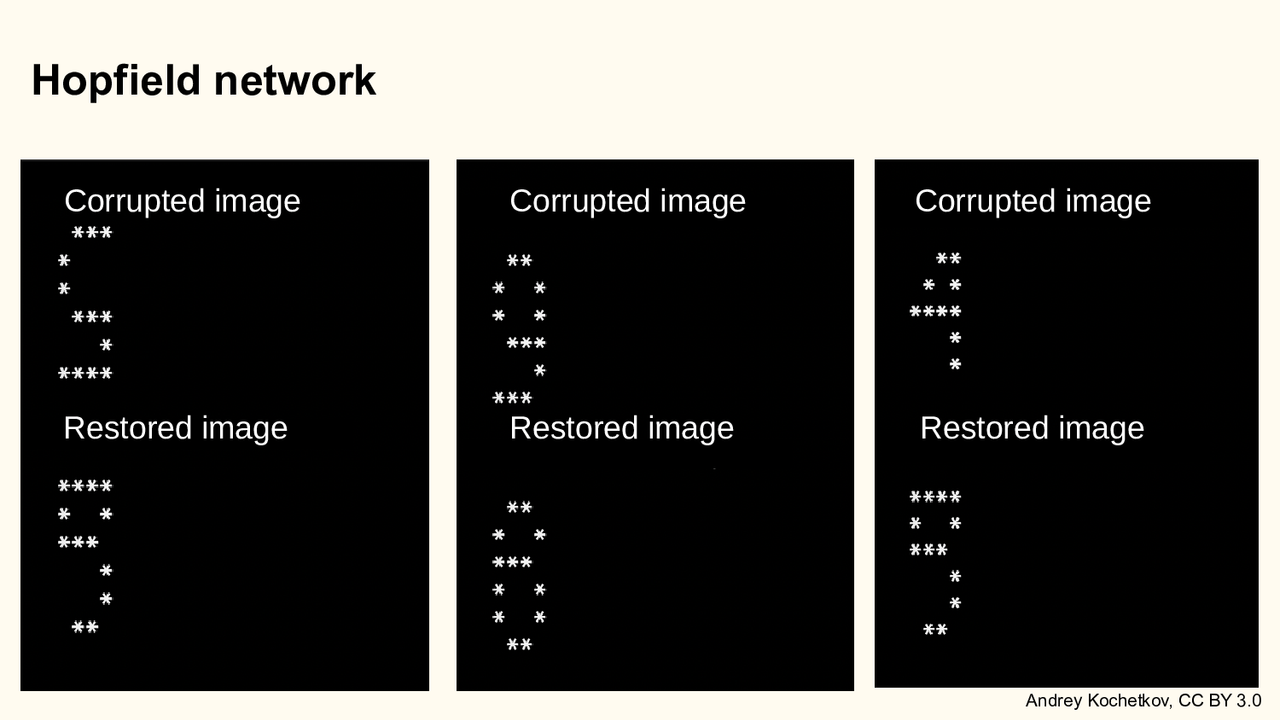

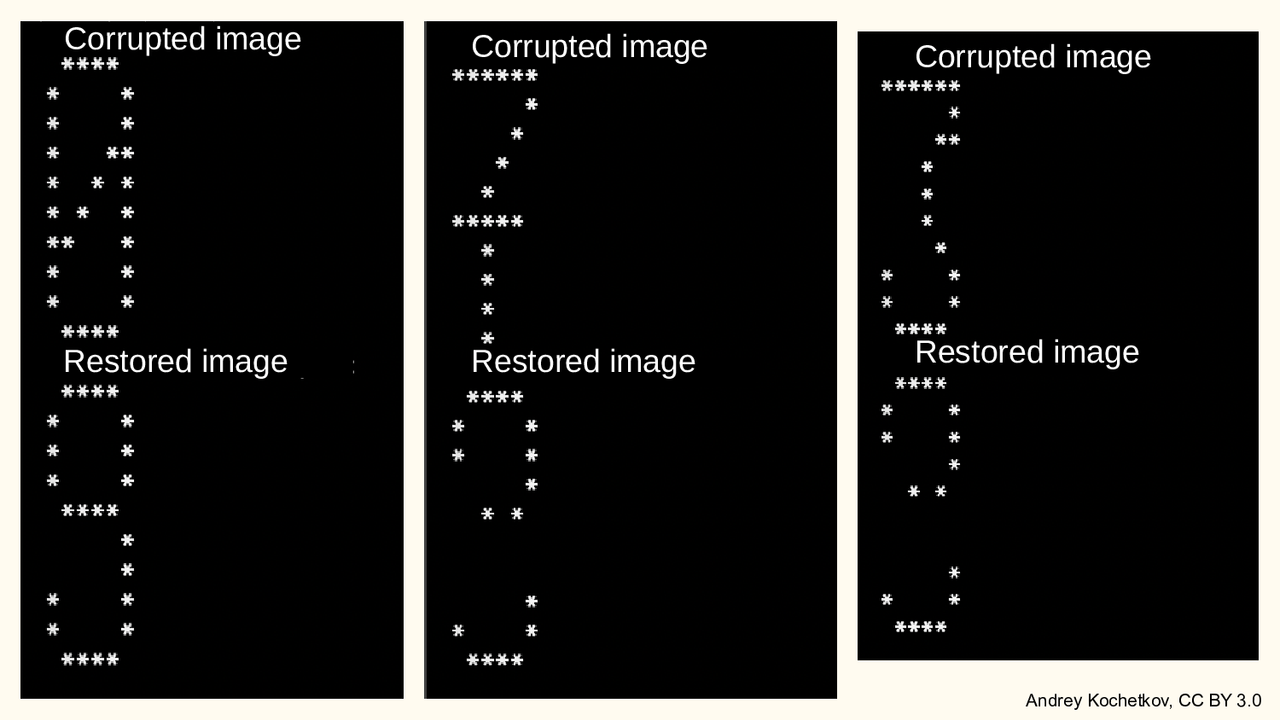

Think of it as a simplified, mathematical version of how the brain works: when we see part of an image or a fragment of a phrase, our mind instinctively fills in the missing details. The Hopfield network works in much the same way – it can “remember” an entire pattern even when it receives only a small fragment of it. Imagine you have just part of the digit “3” in an image; the network can reconstruct the rest. In training, the network builds connections between pixels: if one pixel is present, there’s a calculated likelihood that another related pixel will also be present.

A key property of the Hopfield network is that it has stable equilibrium states. For example, imagine it has been trained on images of the digits 0-9. Even if you feed it a noisy, partially corrupted “5”, it will converge to the correct stored image. In general, such a network can store a number of patterns equal to about 15% of its neuron count. Interestingly, it can also settle into equilibrium states it was never trained on – these are called chimeras.

Hopfield’s idea captured the attention of physicists, neuroscientists, and computer scientists alike, building a bridge between physics and computational models of the brain.

The second laureate, Geoffrey Hinton – often called the “Godfather of Deep Learning” – made equally transformative contributions. In the 1980s, he proposed Boltzmann machines, capable of modeling probabilistic processes and helping neural networks learn. His key breakthrough was showing that networks could be trained via backpropagation – the process of adjusting internal weights by propagating error signals backward through the layers. This was a decisive leap forward, enabling much greater accuracy and laying the groundwork for modern deep learning – technology now used everywhere, from voice assistants to self-driving cars.

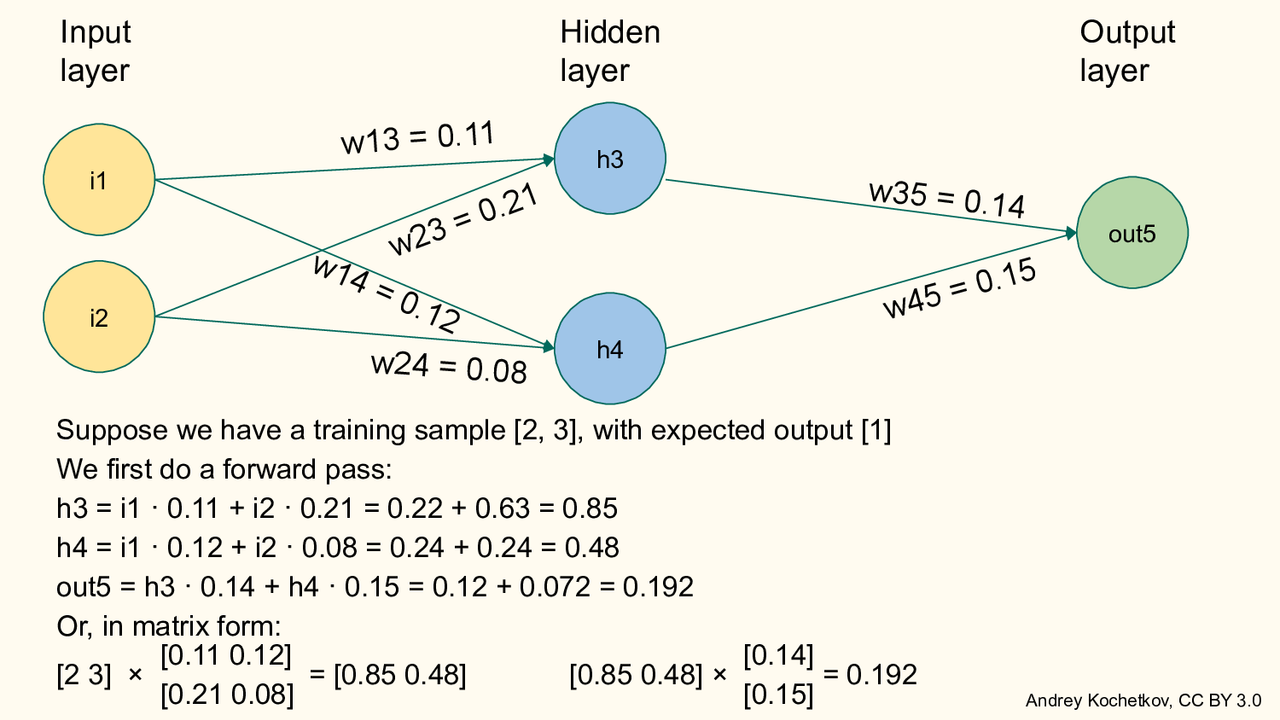

During neural network training, we start with a set of input data and the corresponding correct answers. First comes the forward pass: the data flows through the network, producing a prediction.

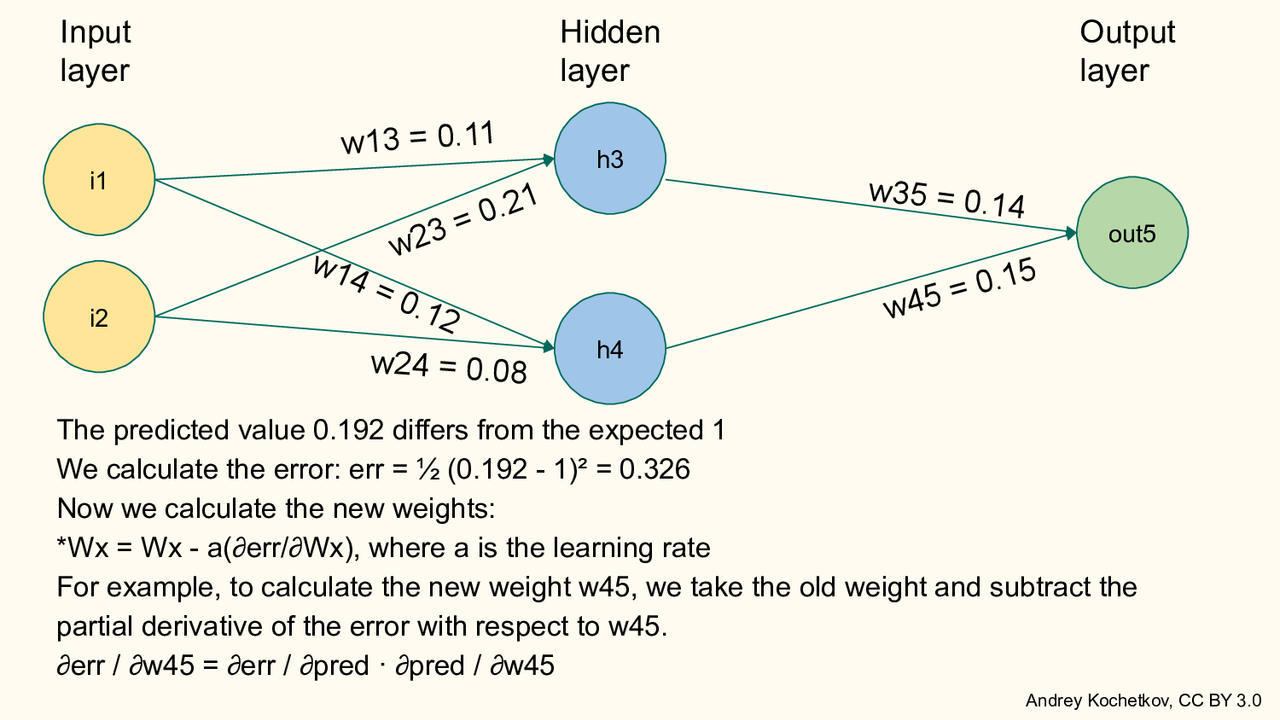

This prediction is then compared with the correct answer,

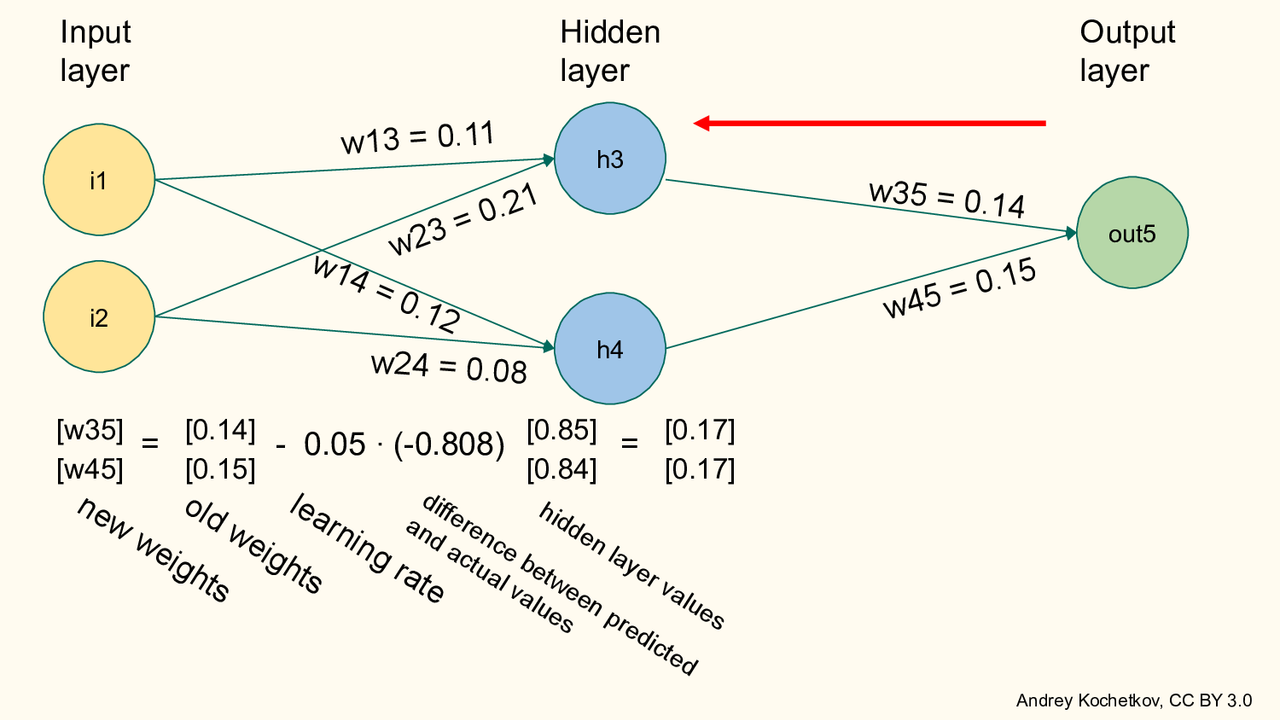

and the resulting error is propagated backward from the output layer through the hidden layers. In the process, the weights of the connections between neurons are adjusted – a procedure known as backpropagation.

The learning rate controls how quickly the network adapts. If it’s too high – say, set to 1 – each new training example would overwrite the network’s previous knowledge. If it’s zero, the network wouldn’t learn at all. In our example, a learning rate of 0.05 means that in a single step, the network moves 1/20 of the way toward the state where it predicts perfectly. But it never actually reaches that state, because the next update is 1/20 of the remaining distance, and so on. After 20 steps, it covers not 100% but only about 65% of the gap.

It was Geoffrey Hinton, together with his students Alex Krizhevsky and Ilya Sutskever, who sparked a revolution in image recognition in 2012. Sutskever is now well known as one of the lead developers of ChatGPT.

GPUs and Neural Networks

Since we’re talking about neural networks, it’s worth touching on why graphics processing units (GPUs) became critical to their development. Originally designed for computer games to handle real-time graphics, GPUs excel at parallel processing –handling many small calculations at once.

In games, GPUs perform vector and matrix operations to compute object movement, lighting, and textures. For example, a game object is described by a set of points with absolute coordinates – a large array of vectors. To determine its position relative to a player’s viewpoint, you multiply each vector by a transformation matrix that can include rotation, translation, and scaling.

Here’s the connection to neural networks: training them also involves massive amounts of vector and matrix operations. Each layer of a network processes huge arrays of numbers, and GPUs – capable of running thousands of these operations simultaneously – are a perfect fit. This hardware-software synergy is what enabled the rapid breakthroughs in AI over the last decade.

The very same kinds of vector and matrix operations also appear in special relativity, neutrino oscillations, and quark interactions. In principle, physicists could have had an extremely powerful tool in GPUs as well – but in practice, the numerical precision of consumer-grade graphics cards is usually insufficient for high-accuracy physics calculations, though it is more than enough for neural networks.

The Hinton Family

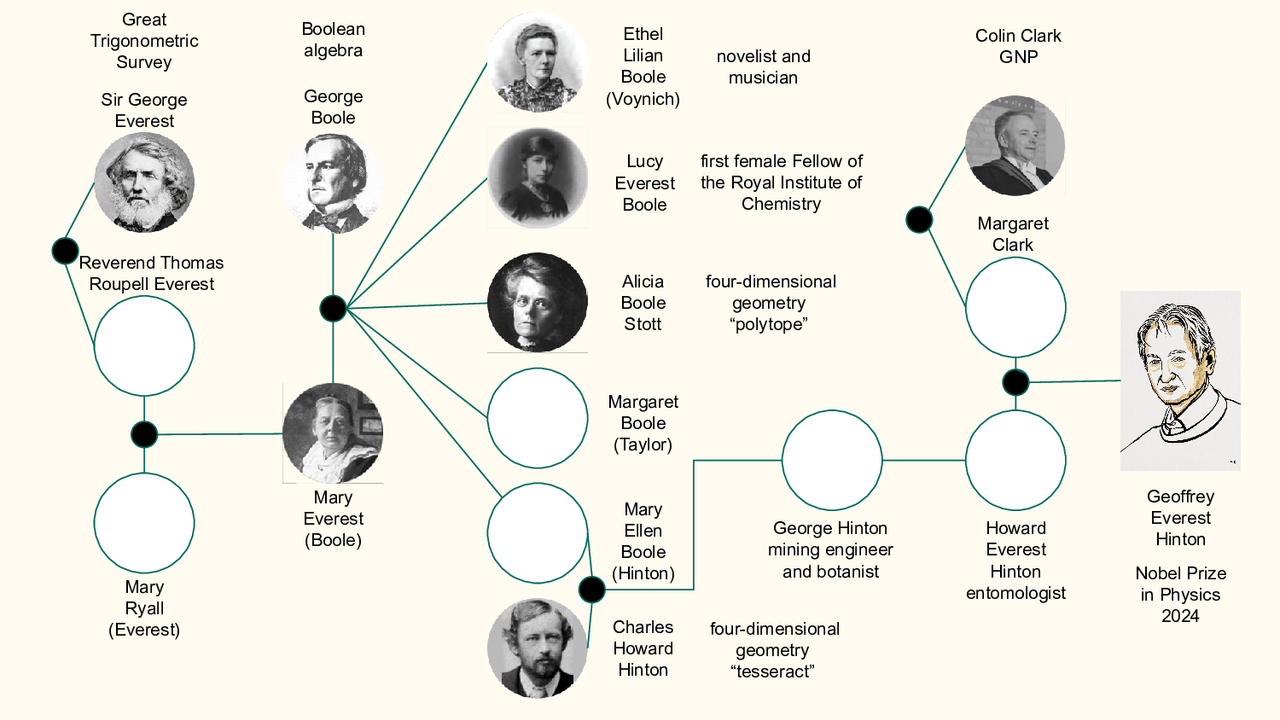

And finally, a few words about Geoffrey Hinton’s remarkable family tree. Many names here may already be familiar to you.

His great-great-grandmother’s uncle was George Everest, the leader of the Great Trigonometrical Survey that first measured Earth’s circumference along the meridians (through the poles) and determined the vertical deflection of a plumb line caused by the uneven distribution of Earth’s mass – in other words, how much mountains can “pull” on an object. The world’s highest mountain was named after him, though Everest himself never actually saw it.

Hinton’s great-great-grandfather was George Boole, creator of Boolean algebra – yes, the very same “bool” or “boolean” type used in programming. His great-great-aunt Ethel Lilian Voynich was the author of The Gadfly, and her husband gave his name to the mysterious Voynich manuscript. Another Hinton’s great-great-aunt was Alicia Stott, who coined the term polytope for a multidimensional generalization of polyhedra, and this great-grandfather was George Hinton, who introduced the term tesseract for a four-dimensional hypercube.

Alicia Stott’s son, Leonard Stott, invented the mobile X-ray unit, and Hinton’s maternal uncle Colin Clark was the economist who introduced the concept of Gross National Product (GNP).