Nobel Peace Prize 2024

Truth about VaccinesIn our 2024 Nobel series: Physics, Physiology or Medicine, Chemistry, Peace Prize

Last but certainly not least among the 2024 Nobel Prizes is the Peace Prize. It was awarded to the Japanese organization Nihon Hidankyo (日本被団協) for its tireless fight for nuclear disarmament and its efforts to preserve the memory of the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Nihon Hidankyo is an association of people who survived the atomic bombings – known in Japan as hibakusha.

In this context, hibakusha (被爆者) literally means “a person affected by the explosion.” Nihon Hidankyo is a national organization of hibakusha that has existed since 1956. Its main goal is to achieve a world free of nuclear weapons and to educate the global public about the consequences of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

From the very beginning, the organization has sought to convey the full horror experienced by the hibakusha, so that no future generation will face the threat of nuclear weapons. They actively participate in international conferences, speak at venues including the United Nations, and engage in dialogue with governments around the world.

Eighty years ago – on August 6 and 9, 1945 – the United States dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The attacks killed over 200,000 people, most of them civilians, in the blasts and in the months and years that followed due to burns, radiation sickness, and related illnesses. Entire families were wiped out in seconds, and survivors faced a lifetime of health problems and social stigma.

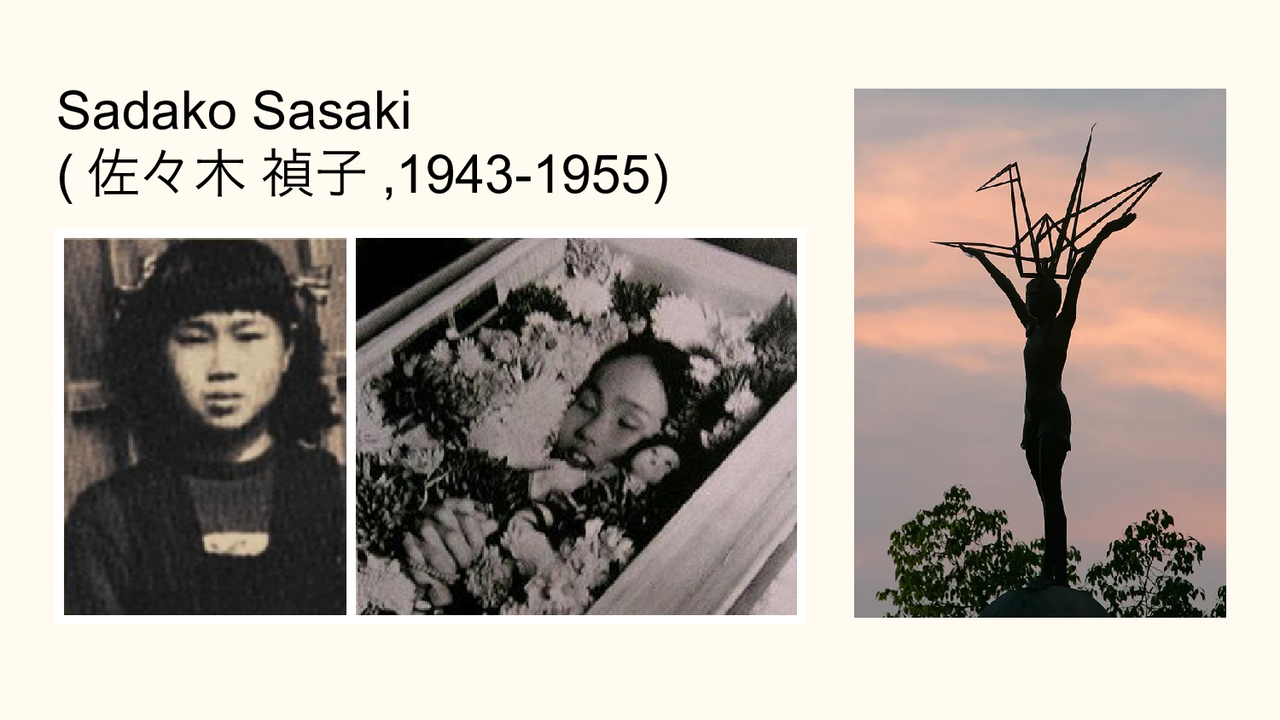

The origami crane featured in the organization’s logo is a reference to the story of Sadako Sasaki, a girl from Hiroshima. Sadako’s home was located about a kilometer and a half from the hypocenter of the explosion. She was just two years old at the time of the atomic attack. In 1954, she was diagnosed with leukemia – a disease that became known in Japan as “the atomic bomb disease.” Her friend told her about a legend: if you fold one thousand origami cranes, the gods will grant your wish.

Sadako folded hundreds of cranes, but her illness worsened. She died in October 1955 at the age of 12. Her funeral became a symbol of the suffering of Hiroshima’s children, and photographs of her coffin remain one of the most haunting reminders of the human cost of nuclear war. Today, if a memorial to the victims of the atomic bombings depicts a child, it is often Sadako Sasaki.

Another example is Reiji Okazaki, who was also caught in the Hiroshima blast. Together with Tsuneko Okazaki, he discovered the so-called Okazaki fragments – short DNA sequences formed during replication on the lagging strand. When Reiji Okazaki presented his discovery, he was already terminally ill. The cause was believed to be radiation exposure from 1945. Despite two decades of medical progress since Sadako’s death, doctors were still powerless to save him. He died in 1975 at the age of 44.

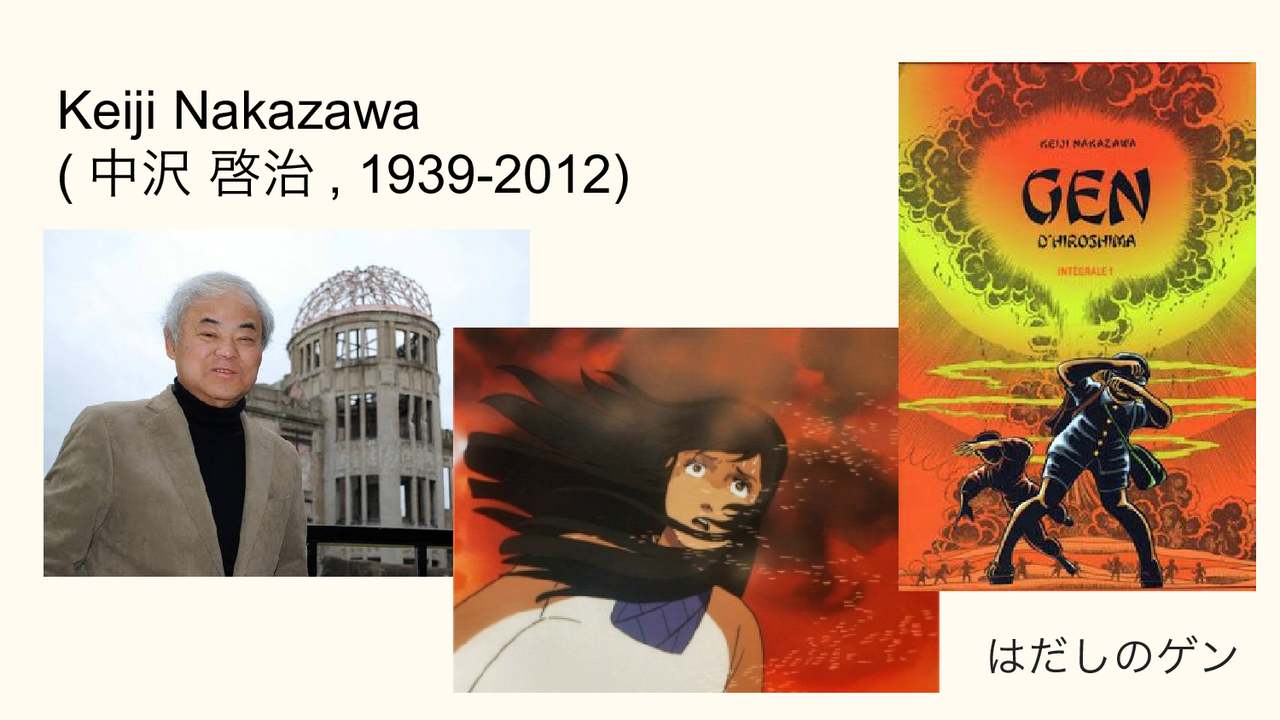

The suffering of hibakusha has also been reflected in Japanese culture. Among the most famous works is I Saw It (おれは見た, Ore wa Mita) by manga artist Keiji Nakazawa, an autobiographical account of the Hiroshima bombing. Later, at the suggestion of his editor, Nakazawa expanded it into Barefoot Gen (はだしのゲン, Hadashi no Gen), which was also adapted into an anime film. Like his protagonist Gen, Nakazawa lost almost his entire family in the bombing.

Alongside Studio Ghibli’s Grave of the Fireflies (火垂るの墓, Hotaru no Haka), created by Isao Takahata and based on a partially autobiographical story, Barefoot Gen is one of the most important works depicting the horrors of the era. These works are not just art – they are historical testimony in illustrated form, ensuring the memories of those events reach audiences who might never open a history book.

The bombings were not the only nuclear disasters in Japan’s history. In 1954, during the Castle Bravo test at Bikini Atoll, a major incident occurred. Due to a misunderstanding of the physics of the lithium-7 isotope, an explosion originally calculated at 6 megatons turned out to have a yield of 15 megatons. The radioactive fallout reached the Japanese fishing vessel Lucky Dragon No. 5 (第五福龍丸, Daigo Fukuryū Maru). While being treated for radiation sickness, the crew contracted hepatitis C; the ship’s radio operator, Aikichi Kuboyama, died seven months later. In Japan, his death became another symbol of how nuclear weapons harm not only those directly targeted, but also people far beyond the battlefield.

Nihon Hidankyo is deeply involved in international campaigns promoting the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, adopted in 2017. The organization advocates for the complete elimination of all nuclear arsenals worldwide and for every country to join the treaty.

It is worth recalling the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons – ICAN – which received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017. The voice of ICAN at the award ceremony was Setsuko Thurlow, née Nakamura, who was 13 years old when she found herself at the epicenter of the Hiroshima blast. In her speech, she recounted surviving under the rubble and watching friends perish in the flames.

Nihon Hidankyo works tirelessly to preserve the testimonies of those who survived the atomic bombings. In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, museums and archives hold artifacts and documents from those days. Survivors continue to speak to students, journalists, and diplomats, repeating their stories again and again – not for themselves, but in the hope that future generations will never need to add new names to the list of nuclear victims.