What every programmer should know about memory, Part 1

SourceThis article brought to you by LWN subscribers

Subscribers to LWN.net made this article — and everything that surrounds it — possible. If you appreciate our content, please buy a subscription and make the next set of articles possible.

[Editor's introduction: Ulrich Drepper recently approached us asking if

we would be interested in publishing a lengthy document he had written on

how memory and software interact. We did not have to look at the text for

long to realize that it would be of interest to many LWN readers. Memory

usage is often the determining factor in how software performs, but good

information on how to avoid memory bottlenecks is hard to find. This

series of articles should change that situation.

The original document prints out at over 100 pages. We will be splitting

it into about seven segments, each run 1-2 weeks after its predecessor.

Once the entire series is out, Ulrich will be releasing the full text.

Reformatting the text from the original LaTeX has been a bit of a

challenge, but the results, hopefully, will be good. For ease of online

reading, Ulrich's footnotes have been placed {inline in the text}.

Hyperlinked cross-references (and [bibliography references]) will not be

possible until the full series is published.

Many thanks to Ulrich for allowing LWN to publish this material; we hope

that it will lead to more memory-efficient software across our systems in

the near future.

1 Introduction

In the early days computers were much simpler. The various components

of a system, such as the CPU, memory, mass storage, and network

interfaces, were developed together and, as a result, were quite

balanced in their performance. For example, the memory and network

interfaces were not (much) faster than the CPU at providing data.

This situation changed once the basic structure of computers

stabilized and hardware developers concentrated on optimizing

individual subsystems. Suddenly the performance of some components of

the computer fell significantly behind and bottlenecks developed.

This was especially true for mass storage and memory subsystems which,

for cost reasons, improved more slowly relative to other components.

The slowness of mass storage has mostly been dealt with using software

techniques: operating systems keep most often used (and most likely to

be used) data in main memory, which can be accessed at a rate orders of

magnitude faster than the hard disk. Cache storage was added to the

storage devices themselves, which requires no changes in the operating system to

increase performance. {Changes are needed, however, to

guarantee data integrity when using storage device caches.} For the

purposes of this paper, we will not go into more details of software

optimizations for the mass storage access.

Unlike storage subsystems, removing the main memory as a bottleneck

has proven much more difficult and almost all solutions require changes to

the hardware. Today these changes mainly come in the following forms:

- RAM hardware design (speed and parallelism).

- Memory controller designs.

- CPU caches.

- Direct memory access (DMA) for devices.

For the most part, this document will deal with CPU caches and some

effects of memory controller design. In the process of exploring

these topics, we will explore DMA and bring it into the larger

picture. However, we will start with an overview of the design for

today's commodity hardware. This is a prerequisite to understanding

the problems and the limitations of efficiently using memory

subsystems. We will also learn about, in some detail, the different types

of RAM and illustrate why these differences still exist.

This document is in no way all inclusive and final. It is limited to

commodity hardware and further limited to a subset of that hardware.

Also, many topics will be discussed in just enough detail

for the goals of this paper. For such topics, readers are recommended to

find more detailed documentation.

When it comes to operating-system-specific details and solutions,

the text exclusively

describes Linux. At no time will it contain any information about

other OSes. The author has no interest in discussing the implications

for other OSes. If the reader thinks s/he has to use a different OS

they have to go to their vendors and demand they write documents

similar to this one.

One last comment before the start. The text contains a number of

occurrences of the term “usually” and other, similar qualifiers.

The technology discussed here exists in many, many

variations in the real world and this paper only addresses the most

common, mainstream versions. It is rare that absolute statements can be

made about this technology, thus the qualifiers.

1.1 Document Structure

This document is mostly for software developers. It does not go into

enough technical details of the hardware to be useful for

hardware-oriented readers. But before we can go into the practical

information for developers a lot of groundwork must be laid.

To that end, the second section describes random-access memory (RAM) in

technical detail. This

section's content is nice to know but not absolutely critical to be able to

understand the later sections. Appropriate back references to the

section are added in places where the content is required so that the

anxious reader could skip most of this section at first.

The third section goes into a lot of details of CPU cache behavior.

Graphs have been used to keep the text from being as dry as it would otherwise

be. This content is essential for an understanding of the rest of the document.

Section 4 describes briefly how virtual memory is implemented. This

is also required groundwork for the rest.

Section 5 goes into a lot of detail about Non Uniform Memory

Access (NUMA) systems.

Section 6 is the central section of this paper. It brings together

all the previous sections' information and gives programmers advice on

how to write code which performs well in the various situations. The

very impatient reader could start with this section and, if necessary, go

back to the earlier sections to freshen up the knowledge of the

underlying technology.

Section 7 introduces tools which can help the programmer do a

better job. Even with a complete understanding of the technology it

is far from obvious where in a non-trivial software project the

problems are. Some tools are necessary.

In section 8 we finally give an outlook of technology which can be

expected in the near future or which might just simply be good to have.

1.2 Reporting Problems

The author intends to update this document for some time. This

includes updates made necessary by advances in technology but also to

correct mistakes. Readers willing to report problems are encouraged

to send email.

1.3 Thanks

I would like to thank Johnray Fuller and especially Jonathan Corbet for taking on part of the

daunting task of transforming the author's form of English into something

more traditional. Markus Armbruster provided a lot of valuable input

on problems and omissions in the text.

1.4 About this Document

The title of this paper is an homage to David Goldberg's classic paper

“What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point

Arithmetic” [goldberg]. Goldberg's paper is still not widely

known, although it should be a prerequisite for anybody daring to

touch a keyboard for serious programming.

Understanding commodity hardware is important because specialized

hardware is in retreat. Scaling these days is most often achieved

horizontally instead of vertically, meaning today it is more cost-effective

to use many smaller, connected commodity computers

instead of a few really large and exceptionally fast (and expensive)

systems. This is the case because fast and inexpensive network

hardware is widely available. There are still situations where the

large specialized systems have their place and these systems still

provide a business opportunity, but the overall market is dwarfed by

the commodity hardware market. Red Hat, as of 2007, expects that for

future products, the “standard building blocks” for most data

centers will be a computer with up to four sockets, each filled with a

quad core CPU that, in the case of Intel CPUs, will be

hyper-threaded. {Hyper-threading enables a single processor core to be used for two or more concurrent executions with just a little extra hardware.} This means the standard system in the data

center will have up to 64 virtual processors. Bigger machines will be

supported, but the quad socket, quad CPU core case is currently

thought to be the sweet spot and most optimizations are targeted for

such machines.

Large differences exist in the structure of commodity computers. That

said, we will cover more than 90% of such hardware by concentrating

on the most important differences. Note that these technical details

tend to change rapidly, so the reader is advised to take the date

of this writing into account.

Over the years the personal computers and smaller servers standardized

on a chipset with two parts: the Northbridge and Southbridge.

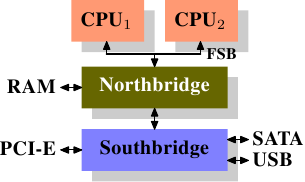

Figure 2.1 shows this structure.

Figure 2.1: Structure with Northbridge and Southbridge

All CPUs (two in the previous example, but there can be more) are

connected via a common bus (the Front Side Bus, FSB) to the

Northbridge. The Northbridge contains, among other things, the memory

controller, and its implementation determines the type of RAM chips

used for the computer. Different types of RAM, such as DRAM, Rambus,

and SDRAM, require different memory controllers.

To reach all other system devices, the Northbridge must communicate with

the Southbridge. The Southbridge, often referred to as the I/O

bridge, handles communication with devices through a variety of

different buses. Today the PCI, PCI Express, SATA, and USB buses are

of most importance, but PATA, IEEE 1394, serial, and parallel ports

are also supported by the Southbridge. Older systems had AGP slots

which were attached to the Northbridge. This was done for performance

reasons related to insufficiently fast connections between the

Northbridge and Southbridge. However, today the PCI-E slots are all

connected to the Southbridge.

Such a system structure has a number of noteworthy consequences:

- All data communication from one CPU to another must travel over the same bus used to communicate with the Northbridge.

- All communication with RAM must pass through the Northbridge.

- The RAM has only a single port.

{We will not discuss multi-port RAM in this document as this

type of RAM is not found in commodity hardware, at least not in places

where the programmer has access to it. It can be found in specialized

hardware such as network routers which depend on utmost speed.} - Communication between a CPU and a device attached to the Southbridge is routed through the Northbridge.

A couple of bottlenecks are immediately apparent in this design. One

such bottleneck involves access to RAM for devices. In the earliest

days of the PC, all communication with devices on either bridge had to

pass through the CPU, negatively impacting overall system performance.

To work around this problem some devices became capable of direct

memory access (DMA). DMA allows devices, with the help of the

Northbridge, to store and receive data in RAM directly without the

intervention of the CPU (and its inherent performance cost). Today all

high-performance devices attached to any of the buses can utilize DMA.

While this greatly reduces the workload on the CPU, it also creates

contention for the bandwidth of the Northbridge as DMA requests

compete with RAM access from the CPUs. This problem, therefore, must

to be taken into account.

A second bottleneck involves the bus from the Northbridge to the RAM.

The exact details of the bus depend on the memory types deployed.

On older systems there is only one bus to all the RAM chips, so

parallel access is not possible. Recent RAM types require

two separate buses (or channels as they are called for DDR2,

see Figure 2.8) which doubles the available bandwidth. The

Northbridge interleaves memory access across the channels. More

recent memory technologies (FB-DRAM, for instance) add more channels.

With limited bandwidth available, it is important to schedule memory

access in ways that minimize delays. As we will see, processors are much faster and

must wait to access memory, despite the use of CPU caches. If multiple

hyper-threads, cores, or processors access memory at the same time,

the wait times for memory access are even longer. This is also true

for DMA operations.

There is more to accessing memory than

concurrency, however. Access patterns themselves also greatly

influence the performance of the memory subsystem, especially with

multiple memory channels. Refer to Section 2.2 for more

details of RAM access patterns.

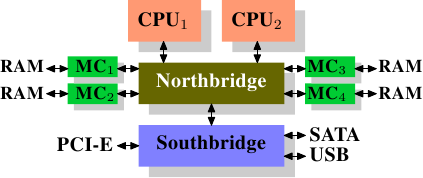

On some more expensive systems, the Northbridge does not actually

contain the memory controller. Instead the Northbridge can be

connected to a number of external memory controllers (in the following

example, four of them).

Figure 2.2: Northbridge with External Controllers

The advantage of this architecture is that more than one memory bus

exists and therefore total bandwidth increases. This design also

supports more memory. Concurrent memory access patterns reduce delays

by simultaneously accessing different memory banks. This is

especially true when multiple processors are directly connected to

the Northbridge, as in Figure 2.2. For such a design, the

primary limitation is the internal bandwidth of the Northbridge, which

is phenomenal for this architecture (from Intel). {For

completeness it should be mentioned that such a memory controller

arrangement can be used for other purposes such as “memory RAID”

which is useful in combination with hotplug memory.}

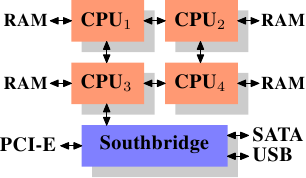

Using multiple external memory controllers is not the only way to

increase memory bandwidth. One other increasingly popular way is to integrate

memory controllers into the CPUs and attach memory to each CPU. This

architecture is made popular by SMP systems based on AMD's Opteron

processor. Figure 2.3 shows such a system. Intel will have

support for the Common System Interface (CSI) starting with the

Nehalem processors; this is basically the same approach: an integrated

memory controller with the possibility of local memory for each

processor.

Figure 2.3: Integrated Memory Controller

With an architecture like this there are as many memory banks

available as there are processors. On a quad-CPU machine the memory

bandwidth is quadrupled without the need for a complicated Northbridge with

enormous bandwidth. Having a memory controller integrated into the

CPU has some additional advantages; we will not dig deeper into this

technology here.

There are disadvantages to this architecture, too. First of all,

because the machine still has to make all the memory of the system

accessible to all processors, the memory is not uniform anymore (hence

the name NUMA - Non-Uniform Memory Architecture - for such an architecture).

Local memory (memory attached to a processor)

can be accessed with the usual speed. The situation is different when

memory attached to another processor is accessed. In this case

the interconnects between the processors have to be used. To access

memory attached to CPU2 from CPU1 requires communication across one

interconnect. When the same CPU accesses memory attached to

CPU4 two interconnects have to be crossed.

Each such communication has an associated cost. We talk about “NUMA

factors” when we describe the extra time needed to access remote

memory. The example architecture in Figure 2.3 has two

levels for each CPU: immediately adjacent CPUs and one CPU

which is two interconnects away. With more

complicated machines the number of levels can grow significantly. There are

also machine architectures (for instance IBM's x445 and SGI's

Altix series) where there is more than one type of connection. CPUs

are organized into nodes; within a node the time to access the

memory might be uniform or have only small NUMA factors. The

connection between nodes can be very expensive, though, and the NUMA

factor can be quite high.

Commodity NUMA machines exist today and will likely play an even greater

role in the future. It is expected that, from late 2008 on, every SMP

machine will use NUMA. The costs associated with NUMA make it important to

recognize when a program is running on a NUMA machine. In

Section 5 we will discuss more machine architectures and some

technologies the Linux kernel provides for these programs.

Beyond the technical details described in the remainder of this

section, there are several additional factors which influence the

performance of RAM. They are not controllable by software, which is

why they are not covered in this section. The interested reader can

learn about some of these factors in Section 2.1. They are really

only needed to get a more complete picture of RAM technology and

possibly to make better decisions when purchasing computers.

The following two sections discuss hardware details at the gate level

and the access protocol between the memory controller and the DRAM

chips. Programmers will likely find this information enlightening since these

details explain why RAM access works the way it does. It is optional

knowledge, though, and the reader anxious to get to topics with more

immediate relevance for everyday life can jump ahead to

Section 2.2.5.

2.1 RAM Types

There have been many types of RAM over the years and each type

varies, sometimes significantly, from the other. The older types are

today really only interesting to the historians. We will not explore

the details of those. Instead we will concentrate on modern RAM types;

we will only scrape the surface, exploring some details which are

visible to the kernel or application developer through their

performance characteristics.

The first interesting details are centered around the question why

there are different types of RAM in the same machine. More

specifically, why there are both static RAM (SRAM {In other contexts

SRAM might mean “synchronous RAM”.}) and dynamic RAM (DRAM). The

former is much faster and provides the same functionality. Why is not

all RAM in a machine SRAM? The answer is, as one might expect, cost.

SRAM is much more expensive to produce and to use than DRAM. Both

these cost factors are important, the second one increasing in

importance more and more. To understand these difference we look at

the implementation of a bit of storage for both SRAM and DRAM.

In the remainder of this section we will discuss some low-level

details of the implementation of RAM. We will keep the level of detail as

low as possible. To that end, we will discuss the signals at a “logic level” and not at

a level a hardware designer would have to use. That level of detail

is unnecessary for our purpose here.

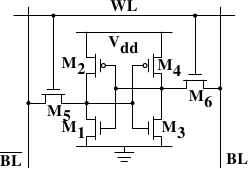

2.1.1 Static RAM

Figure 2.4: 6-T Static RAM

Read Next page