What every programmer should know about memory, Part 1

Source

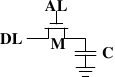

Figure 2.4 shows the structure of a 6 transistor SRAM cell.

The core of this cell is formed by the four transistors M1

to M4 which form two cross-coupled inverters. They have

two stable states, representing 0 and 1 respectively. The state is

stable as long as power on Vdd is available.

If access to the state of the cell is needed the word access line

WL is raised. This makes the state of the cell immediately

available for reading on BL and

BL. If the cell state must be

overwritten the BL and BL

lines are first set to the desired values and then WL is

raised. Since the outside drivers are stronger than the four

transistors (M1 through M4) this

allows the old state to be overwritten.

See [sramwiki] for a more detailed description of the way the cell works.

For the following discussion it is important to note that

- one cell requires six transistors. There are variants with four transistors but they have disadvantages.

- maintaining the state of the cell requires constant power.

- the cell state is available for reading almost immediately once the word access line WL is raised. The signal is as rectangular (changing quickly between the two binary states) as other transistor-controlled signals.

- the cell state is stable, no refresh cycles are needed.

There are other, slower and less power-hungry, SRAM forms available, but

those are not of interest here since we are looking at fast RAM.

These slow variants are mainly interesting because they can be more

easily used in a system than dynamic RAM because of their

simpler interface.

2.1.2 Dynamic RAM

Dynamic RAM is, in its structure, much simpler than static RAM.

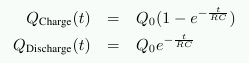

Figure 2.5 shows the structure of a usual DRAM cell design.

All it consists of is one transistor and one capacitor. This huge

difference in complexity of course means that it functions very differently

than static RAM.

Figure 2.5: 1-T Dynamic RAM

A dynamic RAM cell keeps its state in the capacitor C. The

transistor M is used to guard the access to the state. To

read the state of the cell the access line AL is raised;

this either causes a current to flow on the data line DL or

not, depending on the charge in the capacitor. To write to the cell the

data line DL is appropriately set and then AL is raised for a time long enough to charge or

drain the capacitor.

There are a number of complications with the design of dynamic RAM.

The use of a capacitor means that reading the cell discharges the

capacitor. The procedure cannot be repeated indefinitely, the

capacitor must be recharged at some point. Even worse, to accommodate

the huge number of cells (chips with 109 or more cells are now

common) the capacity to the capacitor must be low (in the femto-farad range

or lower). A fully charged capacitor holds a few 10's of thousands of

electrons. Even though the resistance of the capacitor is high (a

couple of tera-ohms) it only takes a short time for the capacity to

dissipate. This problem is called “leakage”.

This leakage is why a DRAM cell must be constantly refreshed. For most DRAM

chips these days this refresh must happen every 64ms. During the refresh cycle no access to

the memory is possible. For some workloads this overhead might stall

up to 50% of the memory accesses (see [highperfdram]).

A second problem resulting from the tiny charge is that the

information read from the cell is not directly usable. The data line

must be connected to a sense amplifier which can distinguish between

a stored 0 or 1 over the whole range of charges which still have to

count as 1.

A third problem is that charging and draining a capacitor is not

instantaneous. The signals received by the sense amplifier are not

rectangular, so a conservative estimate as to when the output of the

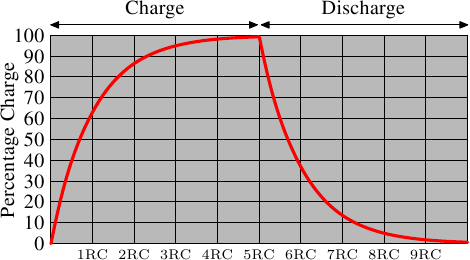

cell is usable has to be used. The formulas for charging and

discharging a capacitor are

This means it takes some time (determined by the capacity C and

resistance R) for the capacitor to be charged and discharged. It also

means that the current which can be detected by the sense amplifiers

is not immediately available. Figure 2.6 shows the charge and

discharge curves. The X—axis is measured in units of RC (resistance

multiplied by capacitance) which is a unit of time.

Figure 2.6: Capacitor Charge and Discharge Timing

Unlike the static RAM case where the output is immediately available when

the word access line is raised, it will always take a bit of time until the

capacitor discharges sufficiently. This delay severely limits how fast

DRAM can be.

The simple approach has its advantages, too. The main advantage is

size. The chip real estate needed for one DRAM cell is many times

smaller than that of an SRAM cell. The SRAM cells also need

individual power for the transistors maintaining the state. The

structure of the DRAM cell is also simpler and more regular which

means packing many of them close together on a die is simpler.

Overall, the (quite dramatic) difference in cost wins. Except in

specialized hardware — network routers, for example — we have to live with main memory

which is based on DRAM. This has huge implications on the programmer

which we will discuss in the remainder of this paper. But first we need

to look into a few more details of the actual use of DRAM cells.

2.1.3 DRAM Access

A program selects a memory location using a virtual address. The

processor translates this into a physical address and finally the

memory controller selects the RAM chip corresponding to that address. To

select the individual memory cell on the RAM chip, parts of the

physical address are passed on in the form of a number of address

lines.

It would be completely impractical to address memory locations

individually from the memory controller: 4GB of RAM would require

232 address lines.

Instead the address is passed encoded as a binary number using a

smaller set of address lines. The address passed to the DRAM chip

this way must be demultiplexed first. A demultiplexer with N

address lines will have 2N output lines. These output lines can be

used to select the memory cell. Using this direct approach is no big

problem for chips with small capacities.

But if the number of cells grows this approach is not suitable

anymore. A chip with 1Gbit

{I hate those SI prefixes. For me

a giga-bit will always be 230 and not 109 bits.} capacity

would need 30 address lines and 230 select lines. The size of a

demultiplexer increases exponentially with the number of input lines

when speed is not to be sacrificed. A demultiplexer for 30 address

lines needs a whole lot of chip real estate in addition to the

complexity (size and time) of the demultiplexer. Even more

importantly, transmitting 30 impulses on the address lines

synchronously is much harder than transmitting “only” 15 impulses.

Fewer lines have to be laid out at exactly the same length or timed

appropriately. {Modern DRAM types like DDR3 can automatically

adjust the timing but there is a limit as to what can be tolerated.}

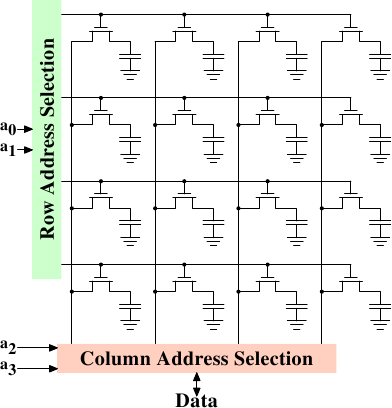

Figure 2.7: Dynamic RAM Schematic

Figure 2.7 shows a DRAM chip at a very high level. The DRAM

cells are organized in rows and columns. They could all be aligned in

one row but then the DRAM chip would need a huge demultiplexer. With

the array approach the design can get by with one demultiplexer and

one multiplexer of half the size. {Multiplexers and

demultiplexers are equivalent and the multiplexer here needs to work

as a demultiplexer when writing. So we will drop the differentiation

from now on.} This is a huge saving on all fronts. In the example

the address lines a0 and

a1 through the row address

selection (RAS)

demultiplexer select the address lines of a whole row of cells. When

reading, the content of all cells is thusly made available to the

column address selection (CAS)

{The line over the name

indicates that the signal is negated} multiplexer. Based on the

address lines a2 and

a3 the content of one column is

then made available to the data pin of the DRAM chip. This happens

many times in parallel on a number of DRAM chips to produce a total

number of bits corresponding to the width of the data bus.

For writing, the new cell value is put on the data bus and, when the

cell is selected using the RAS and CAS, it is stored in the cell.

A pretty straightforward design. There are in reality — obviously — many

more complications. There need to be specifications for how much delay there

is after the signal before the data will be available on the data bus for

reading. The capacitors do not unload instantaneously, as described

in the previous section. The signal from the cells is so weak that

it needs to be amplified. For writing it must be specified how long

the data must be available on the bus after the RAS and CAS is

done to successfully store the new value in the cell (again, capacitors

do not fill or drain instantaneously). These timing constants are

crucial for the performance of the DRAM chip. We will talk about this

in the next section.

A secondary scalability problem is that having 30 address lines

connected to every RAM chip is not feasible either. Pins of a chip

are a precious resources. It is “bad” enough that the data must be

transferred as much as possible in parallel (e.g., in 64 bit batches).

The memory controller must be able to address each RAM module

(collection of RAM chips). If parallel access to multiple RAM modules

is required for performance reasons and each RAM module requires its own

set of 30 or more address lines, then the memory controller needs to

have, for 8 RAM modules, a whopping 240+ pins only for the address

handling.

To counter these secondary scalability problems DRAM chips have, for a long

time, multiplexed the address itself. That means the address is

transferred in two parts. The first part consisting of address bits

a0 and

a1 in the example in

Figure 2.7) select the row. This selection remains active

until revoked. Then the second part, address bits

a2 and

a3, select the column. The

crucial difference is that only two external address lines are needed.

A few more lines are needed to indicate when the RAS and CAS signals

are available but this is a small price to pay for cutting the number

of address lines in half. This address multiplexing brings its own

set of problems, though. We will discuss them in Section 2.2.

2.1.4 Conclusions

Do not worry if the details in this section are a bit overwhelming.

The important things to take away from this section are:

- there are reasons why not all memory is SRAM

- memory cells need to be individually selected to be used

- the number of address lines is directly responsible for the cost of the memory controller, motherboards, DRAM module, and DRAM chip

- it takes a while before the results of the read or write operation are available

The following section will go into more details about the actual

process of accessing DRAM memory. We are not going into more details

of accessing SRAM, which is usually directly addressed. This happens

for speed and because the SRAM memory is limited in size. SRAM is

currently used in CPU caches and on-die where the connections are small

and fully under control of the CPU designer. CPU caches are a topic

which we discuss later but all we need to know is that SRAM cells have

a certain maximum speed which depends on the effort spent on the

SRAM. The speed can vary from only slightly slower than the CPU core

to one or two orders of magnitude slower.

2.2 DRAM Access Technical Details

In the section introducing DRAM we saw that DRAM chips multiplex the

addresses in order to save resources. We also saw that accessing DRAM

cells takes time since the capacitors in those cells do not discharge instantaneously

to produce a stable signal; we also saw that DRAM cells must be

refreshed. Now it is time to put this all together and see how all

these factors determine how the DRAM access has to happen.

We will concentrate on current technology; we will not discuss

asynchronous DRAM and its variants as they are simply not relevant

anymore. Readers interested in this topic are referred to

[highperfdram] and [arstechtwo]. We will also not talk about

Rambus DRAM (RDRAM) even though the technology is not obsolete. It is just not widely used for system

memory. We will concentrate exclusively

on Synchronous DRAM (SDRAM) and its successors Double Data Rate DRAM

(DDR).

Synchronous DRAM, as the name suggests, works relative to a time

source. The memory controller provides a clock, the frequency of

which determines the speed of the Front Side Bus (FSB) —

the memory controller interface used by the DRAM chips. As of this writing,

frequencies of 800MHz, 1,066MHz, or even 1,333MHz are available with

higher frequencies (1,600MHz) being announced for the next generation. This

does not mean the frequency used on the bus is actually this high.

Instead, today's buses are double- or quad-pumped, meaning that data is

transported two or four times per cycle. Higher numbers sell so the

manufacturers like to advertise a quad-pumped 200MHz bus as an

“effective” 800MHz bus.

For SDRAM today each data transfer consists of 64 bits — 8 bytes. The

transfer rate of the FSB is therefore 8 bytes multiplied by the effective

bus frequency (6.4GB/s for the quad-pumped 200MHz bus). That sounds like a

lot but it is the burst speed, the maximum speed which will never be

surpassed. As we will see now the protocol for talking

to the RAM modules has a lot of downtime when no data can be transmitted.

It is exactly this downtime which we must understand and minimize to

achieve the best performance.

2.2.1 Read Access Protocol

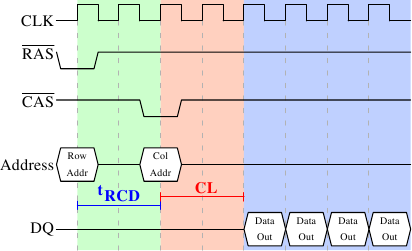

Figure 2.8: SDRAM Read Access Timing

Figure 2.8 shows the activity on some of the connectors of

a DRAM module which happens in three differently colored phases. As

usual, time flows from left to right. A lot of details are left out.

Here we only talk about the bus clock, RAS and CAS signals, and

the address and data buses. A read cycle begins with the memory

controller making the row address available on the address bus and

lowering the RAS signal. All signals are read on the rising edge

of the clock (CLK) so it does not matter if the signal is not

completely square as long as it is stable at the time it is read.

Setting the row address causes the RAM chip to start latching the

addressed row.

The CAS signal can be sent after tRCD (RAS-to-CAS Delay)

clock cycles. The column address is then transmitted by making it

available on the address bus and lowering the CAS line. Here we

can see how the two parts of the address (more or less halves, nothing

else makes sense) can be transmitted over the same address bus.

Now the addressing is complete and the data can be transmitted. The

RAM chip needs some time to prepare for this. The delay is usually

called CAS Latency (CL). In Figure 2.8 the CAS

latency is 2. It can be higher or lower, depending on the quality of

the memory controller, motherboard, and DRAM module. The latency can

also have half values. With CL=2.5 the first data would be available

at the first falling flank in the blue area.

With all this preparation to get to the data it would be wasteful to

only transfer one data word. This is why DRAM modules allow the

memory controller to specify how much data is to be transmitted.

Often the choice is between 2, 4, or 8 words. This allows filling

entire lines in the caches without a new RAS/CAS sequence. It is also

possible for the memory controller to send a new CAS signal without

resetting the row selection. In this way, consecutive memory addresses

can be read from or written to significantly faster because the RAS signal does not have to be sent and the row does

not have to be deactivated (see below). Keeping the row “open” is

something the memory controller has to decide. Speculatively leaving

it open all the time has disadvantages with real-world applications

(see [highperfdram]). Sending new CAS signals is only subject

to the Command Rate of the RAM module (usually specified as Tx,

where x is a value like 1 or 2; it will be 1 for high-performance DRAM

modules which accept new commands every cycle).

In this example the SDRAM spits out one word per cycle. This is what

the first generation does. DDR is able to transmit two words per

cycle. This cuts down on the transfer time but does not change the

latency. In principle, DDR2 works the same although in practice it

looks different. There is no need to go into the details here. It is

sufficient to note that DDR2 can be made faster, cheaper, more

reliable, and is more energy efficient (see [ddrtwo] for more

information).

2.2.2 Precharge and Activation

Figure 2.8 does not cover the whole cycle. It only shows

parts of the full cycle of accessing DRAM. Before a new RAS signal

can be sent the currently latched row must be deactivated and the new

row must be precharged. We can concentrate here on the case where

this is done with an explicit command. There are improvements to the

protocol which, in some situations, allows this extra step to be avoided. The

delays introduced by precharging still affect the operation, though.

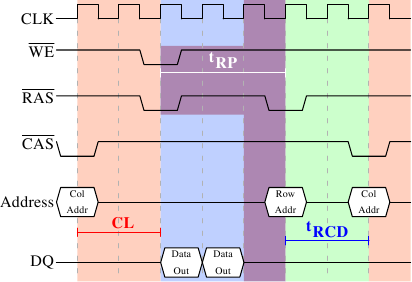

Figure 2.9: SDRAM Precharge and Activation

Figure 2.9 shows the activity starting from one CAS

signal to the CAS signal for another row. The data requested with

the first CAS signal is available as before, after CL cycles. In the

example two words are requested which, on a simple SDRAM, takes two

cycles to transmit. Alternatively, imagine four words on a DDR chip.

Even on DRAM modules with a command rate of one the precharge command

cannot be issued right away. It is necessary to wait as long as it

takes to transmit the data. In this case it takes two cycles. This

happens to be the same as CL but that is just a coincidence. The

precharge signal has no dedicated line; instead, some implementations

issue it by

lowering the Write Enable (WE) and RAS line simultaneously. This

combination has no useful meaning by itself (see [micronddr] for

encoding details).

Once the precharge command is issued it takes tRP (Row Precharge

time) cycles until the row can be selected. In Figure 2.9

much of the time (indicated by the purplish color) overlaps with the

memory transfer (light blue). This is good! But tRP is larger than

the transfer time and so the next RAS signal is stalled for one

cycle.

If we were to continue the timeline in the diagram we would find that

the next data transfer happens 5 cycles after the previous one stops.

This means the data bus is only in use two cycles out of seven.

Multiply this with the FSB speed and the theoretical 6.4GB/s for a

800MHz bus become 1.8GB/s. That is bad and must be avoided. The

techniques described in Section 6 help to raise this number.

But the programmer usually has to do her share.

There is one more timing value for a SDRAM module which we have not

discussed. In Figure 2.9 the precharge command was only

limited by the data transfer time. Another constraint is that an

SDRAM module needs time after a RAS signal before it can precharge

another row (denoted as tRAS). This number is usually pretty high,

in the order of two or three times the tRP value. This is a

problem if, after a RAS signal, only one CAS signal follows

and the data transfer is finished in a few cycles. Assume that in

Figure 2.9 the initial CAS signal was preceded directly

by a RAS signal and that tRAS is 8 cycles. Then the precharge

command would have to be delayed by one additional cycle since the sum of

tRCD, CL, and tRP (since it is larger than the data transfer time)

is only 7 cycles.

DDR modules are often described using a special notation: w-x-y-z-T.

For instance: 2-3-2-8-T1. This means:

w 2 CAS Latency (CL) x 3 RAS-to-CAS delay (tRCD) y 2 RAS

Precharge (tRP) z 8 Active to Precharge delay (tRAS) T T1 Command Rate

There are numerous other timing constants which affect the way

commands can be issued and are handled. Those five constants are in

practice sufficient to determine the performance of the module, though.

It is sometimes useful to know this information for the computers in

use to be able to interpret certain measurements. It is

definitely useful to know these details when buying computers since

they, along with the FSB and SDRAM module speed, are

among the most important factors determining a computer's speed.

Read Next page