What every programmer should know about memory, Part 1

Source

The very adventurous reader could also try to tweak a system.

Sometimes the BIOS allows changing some or all these values. SDRAM

modules have programmable registers where these values can be set.

Usually the BIOS picks the best default value. If the quality of the

RAM module is high it might be possible to reduce the one or the other

latency without affecting the stability of the computer. Numerous

overclocking websites all around the Internet provide ample of

documentation for doing this. Do it at your own risk, though and do not say

you have not been warned.

2.2.3 Recharging

A mostly-overlooked topic when it comes to DRAM access is recharging.

As explained in Section 2.1.2, DRAM cells must constantly be refreshed.

This does not happen completely transparently for the rest of the

system. At times when a row {Rows are the granularity this

happens with despite what [highperfdram] and other literature

says (see [micronddr]).} is recharged no access is possible. The

study in [highperfdram] found that “[s]urprisingly, DRAM

refresh organization can affect performance dramatically”.

Each DRAM cell must be refreshed every 64ms according to the JEDEC

specification. If a DRAM array has 8,192 rows this means the memory

controller has to issue a refresh command on average every

7.8125µs (refresh commands can be queued so in practice the

maximum interval between two requests can be higher). It is the

memory controller's responsibility to schedule the refresh commands.

The DRAM module keeps track of the address of the last refreshed row

and automatically increases the address counter for each new request.

There is really not much the programmer can do about the refresh and

the points in time when the commands are issued. But it is important

to keep this part to the DRAM life cycle in mind when interpreting

measurements. If a critical word has to be retrieved from a row which

currently is being refreshed the processor could be stalled for quite a long

time. How long each refresh takes depends on the DRAM module.

2.2.4 Memory Types

It is worth spending some time on the current and soon-to-be current

memory types in use. We will start with SDR (Single Data Rate) SDRAMs

since they are the basis of the DDR (Double Data Rate) SDRAMs. SDRs

were pretty simple. The memory cells and the data transfer rate were

identical.

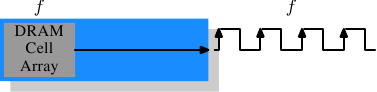

Figure 2.10: SDR SDRAM Operation

In Figure 2.10 the DRAM cell array can output the memory content at

the same rate it can be transported over the memory bus. If the DRAM

cell array can operate at 100MHz, the data transfer rate of the bus is thus

100Mb/s. The frequency f for all components is the same.

Increasing the throughput of the DRAM chip is expensive since the

energy consumption rises with the frequency. With a huge number of

array cells this is prohibitively expensive. {Power = Dynamic

Capacity × Voltage2 × Frequency.} In reality it is

even more of a problem since increasing the frequency usually also

requires increasing the voltage to maintain stability of the system.

DDR SDRAM (called DDR1

retroactively) manages to improve the throughput without increasing

any of the involved frequencies.

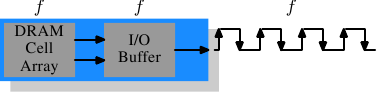

Figure 2.11: DDR1 SDRAM Operation

The difference between SDR and DDR1 is, as can be seen in

Figure 2.11 and guessed from the name, that twice the amount of

data is transported per cycle. I.e., the DDR1 chip transports data on

the rising and falling edge. This is sometimes called a

“double-pumped” bus. To make this possible without increasing the

frequency of the cell array a buffer has to be introduced. This

buffer holds two bits per data line. This in turn requires that, in

the cell array in Figure 2.7, the data bus consists of two

lines. Implementing this is trivial: one only has the use the same

column address for two DRAM cells and access them in parallel. The

changes to the cell array to implement this are also minimal.

The SDR

DRAMs were known simply by their frequency (e.g., PC100 for 100MHz

SDR). To make DDR1 DRAM sound better the marketers had to come up

with a new scheme since the frequency did not change. They came with

a name which contains the transfer rate in bytes a DDR module (they

have 64-bit busses) can sustain:

100MHz × 64bit × 2 = 1,600MB/s

Hence a DDR module with 100MHz frequency is called PC1600. With 1600

> 100 all marketing requirements are fulfilled; it sounds much

better although the improvement is really only a factor of

two. {I will take the factor of two but I do not have to like the inflated numbers.}

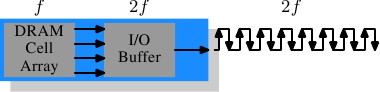

Figure 2.12: DDR2 SDRAM Operation

To get even more out of the memory technology DDR2 includes a bit more

innovation. The most obvious change that can be seen in

Figure 2.12 is the doubling of the frequency of the bus.

Doubling the frequency means doubling the bandwidth. Since this

doubling of the frequency is not economical for the cell array it is

now required that the I/O buffer gets four bits in each clock cycle

which it then can send on the bus. This means the changes to the DDR2

modules consist of making only the I/O buffer component of the DIMM

capable of running at higher speeds. This is certainly possible and

will not require measurably more energy, it is just one tiny component and

not the whole module. The names the marketers came up with for DDR2

are similar to the DDR1 names only in the computation of the value the

factor of two is replaced by four (we now have a quad-pumped bus).

Figure 2.13 shows the names of the modules in use today.

Array

Freq.

Bus

Freq.

Data

Rate

Name

(Rate)

Name

(FSB) 133MHz 266MHz 4,256MB/s PC2-4200 DDR2-533

166MHz 333MHz 5,312MB/s PC2-5300 DDR2-667

200MHz 400MHz 6,400MB/s PC2-6400 DDR2-800

250MHz 500MHz 8,000MB/s PC2-8000 DDR2-1000

266MHz 533MHz 8,512MB/s PC2-8500 DDR2-1066Figure 2.13: DDR2 Module Names

There is one more twist to the naming. The FSB speed used by CPU,

motherboard, and DRAM module is specified by using the

effective frequency. I.e., it factors in the transmission on both flanks of the clock cycle and thereby inflates

the number. So, a 133MHz module with a 266MHz bus has an FSB

“frequency” of 533MHz.

The specification for DDR3 (the real one, not the fake GDDR3 used in

graphics cards) calls for more changes along the lines of the

transition to DDR2. The voltage will be reduced from 1.8V

for DDR2 to 1.5V for DDR3. Since the power consumption equation is

calculated using the square of the voltage this alone brings a

30% improvement. Add to this a reduction in die size plus other

electrical advances and DDR3 can manage, at the same frequency, to get

by with half the power consumption. Alternatively, with higher

frequencies, the same power envelope can be hit. Or with double the

capacity the same heat emission can be achieved.

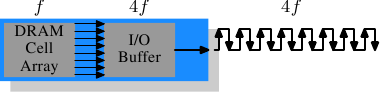

The cell array of DDR3 modules will run at a quarter of the speed of

the external bus which requires an 8 bit I/O buffer, up from 4 bits

for DDR2. See Figure 2.14 for the schematics.

Figure 2.14: DDR3 SDRAM Operation

Initially DDR3 modules will likely have slightly higher CAS

latencies just because the DDR2 technology is more mature. This would

cause DDR3 to be useful only at frequencies which are higher than those

which can be achieved with DDR2, and, even then, mostly when bandwidth is more

important than latency. There is already talk about 1.3V modules

which can achieve the same CAS latency as DDR2. In any case, the

possibility of achieving higher speeds because of faster buses will

outweigh the increased latency.

One possible problem with DDR3 is that, for 1,600Mb/s transfer rate or

higher, the number of modules per channel may be reduced to just one.

In earlier versions this requirement held for all frequencies, so one can hope that the requirement will at some point be lifted for all

frequencies. Otherwise the capacity of systems will be severely limited.

Figure 2.15 shows the names of the expected DDR3 modules.

JEDEC agreed so far on the first four types. Given that Intel's 45nm

processors have an FSB speed of 1,600Mb/s, the 1,866Mb/s is needed for

the overclocking market. We will likely see more of this towards the end

of the DDR3 lifecycle.

Array

Freq.

Bus

Freq.

Data

Rate

Name

(Rate)

Name

(FSB) 100MHz 400MHz 6,400MB/s PC3-6400 DDR3-800

133MHz 533MHz 8,512MB/s PC3-8500 DDR3-1066

166MHz 667MHz 10,667MB/s PC3-10667 DDR3-1333

200MHz 800MHz 12,800MB/s PC3-12800 DDR3-1600

233MHz 933MHz 14,933MB/s PC3-14900 DDR3-1866Figure 2.15: DDR3 Module Names

All DDR memory has one problem: the increased bus frequency makes it

hard to create parallel data busses. A DDR2 module has 240 pins. All

connections to data and address pins must be routed so that they have

approximately the same length. Even more of a problem is that, if more

than one DDR module is to be daisy-chained on the same bus, the signals

get more and more distorted for each additional module. The DDR2

specification allow only two modules per bus (aka channel), the DDR3

specification only one module for high frequencies. With 240 pins per

channel a single Northbridge cannot reasonably drive more than two

channels. The alternative is to have external memory controllers (as

in Figure 2.2) but this is expensive.

What this means is that commodity motherboards are restricted to hold

at most four DDR2 or DDR3 modules. This restriction severely limits the

amount of memory a system can have. Even old 32-bit IA-32 processors

can handle 64GB of RAM and memory demand even for home use is growing,

so something has to be done.

One answer is to add memory controllers into each processor as

explained in Section 2. AMD does it with the Opteron

line and Intel will do it with their CSI technology. This will help

as long as the reasonable amount of memory a processor is able to use

can be connected to a single processor. In some situations this is

not the case and this setup will introduce a NUMA architecture and its negative

effects. For some situations another solution is needed.

Intel's answer to this problem for big server machines, at least for

the next years, is called Fully

Buffered DRAM (FB-DRAM). The FB-DRAM modules use the same components

as today's DDR2 modules which makes them relatively cheap to produce.

The difference is in the connection with the memory controller.

Instead of a parallel data bus FB-DRAM utilizes a serial bus (Rambus

DRAM had this back when, too, and SATA is the successor of PATA, as is

PCI Express for PCI/AGP). The serial bus can be driven at a much

higher frequency, reverting the negative impact of the serialization and

even increasing the bandwidth. The main effects of using a serial bus

are

- more modules per channel can be used.

- more channels per Northbridge/memory controller can be used.

- the serial bus is designed to be fully-duplex (two lines).

An FB-DRAM module has only 69 pins, compared with the 240 for DDR2.

Daisy chaining FB-DRAM modules is much easier since the electrical

effects of the bus can be handled much better. The FB-DRAM

specification allows up to 8 DRAM modules per channel.

Compared with the connectivity requirements of a dual-channel

Northbridge it is now possible to drive 6 channels of FB-DRAM with

fewer pins: 2×240 pins versus 6×69 pins. The routing

for each channel is much simpler which could also help reducing the

cost of the motherboards.

Fully duplex parallel busses are prohibitively expensive for the

traditional DRAM modules, duplicating all those lines is too costly.

With serial lines (even if they are differential, as FB-DRAM requires)

this is not the case and so the serial bus is designed to be fully

duplexed, which means, in some situations, that the bandwidth is theoretically

doubled alone by this. But it is not the only place where parallelism

is used for bandwidth increase. Since an FB-DRAM controller can run

up to six channels at the same time the bandwidth can be increased

even for systems with smaller amounts of RAM by using FB-DRAM. Where

a DDR2 system with four modules has two channels, the same capacity can

handled via four channels using an ordinary FB-DRAM controller. The

actual bandwidth of the serial bus depends on the type of DDR2 (or

DDR3) chips used on the FB-DRAM module.

We can summarize the advantages like this:

DDR2 FB-DRAM

Pins 240 69

Channels 2 6

DIMMs/Channel 2 8

Max Memory 16GB 192GB

Throughput ~10GB/s ~40GB/s

There are a few drawbacks to FB-DRAMs if multiple DIMMs on one channel

are used. The signal is delayed—albeit minimally—at each DIMM in the

chain, which means the latency increases. But for the same amount of

memory with the same frequency FB-DRAM can always be faster than DDR2

and DDR3 since only one DIMM per channel is needed; for large

memory systems DDR simply has no answer using commodity components.

2.2.5 Conclusions

This section should have shown that accessing DRAM is not an

arbitrarily fast process. At least not fast compared with the speed

the processor is running and with which it can access registers and

cache. It is important to keep in mind the differences between CPU and

memory frequencies. An Intel Core 2 processor running at 2.933GHz and a

1.066GHz FSB have a clock ratio of 11:1 (note: the 1.066GHz bus is

quad-pumped). Each stall of one cycle on the memory bus means a stall

of 11 cycles for the processor. For most machines the actual DRAMs

used are slower, thusly increasing the delay. Keep these numbers in

mind when we are talking about stalls in the upcoming sections.

The timing charts for the read command have shown that DRAM modules

are capable of high sustained data rates. Entire DRAM rows could be

transported without a single stall. The data bus could be kept

occupied 100%. For DDR modules this means two 64-bit words

transferred each cycle. With DDR2-800 modules and two channels this

means a rate of 12.8GB/s.

But, unless designed this way, DRAM access is not always sequential.

Non-continuous memory regions are used which means precharging and new

RAS signals are needed. This is when things slow down and when the

DRAM modules need help. The sooner the precharging can happen and the

RAS signal sent the smaller the penalty when the row is actually

used.

Hardware and software prefetching (see Section 6.3) can be used

to create more overlap in the timing and reduce the stall.

Prefetching also helps shift memory operations in time so that there

is less contention at later times, right before the data is actually

needed. This is a frequent problem when the data produced in one

round has to be stored and the data required for the next round has to be

read. By shifting the read in time, the write and read operations do

not have to be issued at basically the same time.

2.3 Other Main Memory Users

Beside the CPUs there are other system components which can access the

main memory. High-performance cards such as network and mass-storage

controllers cannot afford to pipe all the data they need or provide

through the CPU. Instead, they read or write the data directly from/to

the main memory (Direct Memory Access, DMA). In Figure 2.1

we can see that the cards can talk through the South- and Northbridge

directly with the memory. Other buses, like USB, also require FSB

bandwidth—even though they do not use DMA—since the Southbridge is

connected to the Northbridge through the FSB, too.

While DMA is certainly beneficial, it means that there is more

competition for the FSB bandwidth. In times with high DMA traffic the

CPU might stall more than usual while waiting for data from the main

memory. There are ways around this given the right hardware. With an

architecture as in Figure 2.3 one can make sure the computation

uses memory on nodes which are not affected by DMA. It is also

possible to attach a Southbridge to each node, equally

distributing the load on the FSB of all the nodes. There are a myriad

of possibilities. In Section 6 we will introduce techniques and

programming interfaces which help achieving the improvements which are

possible in software.

Finally it should be mentioned that some cheap systems have graphics

systems without separate, dedicated video RAM. Those systems use

parts of the main memory as video RAM. Since access to the video RAM

is frequent (for a 1024x768 display with 16 bpp at 60Hz we are talking

94MB/s) and system memory, unlike RAM on graphics cards, does not have

two ports this can substantially influence the systems performance

and especially the latency. It is best to ignore such systems

when performance is a priority. They are more trouble than they are worth.

People buying those machines know they will not get the best

performance.

Continue to:

- Part 2 (CPU caches)

- Part 3 (Virtual memory)

- Part 4 (NUMA systems)

- Part 5 (What programmers can do - cache optimization)

- Part 6 (What programmers

can do - multi-threaded optimizations) - Part 7 (Memory

performance tools) - Part 8 (Future technologies)

- Part 9 (Appendices and bibliography)

Index entries for this article GuestArticlesDrepper, Ulrich

(Log in to post comments)