Mom And Son Sexual Game Battle

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

IE 11 is not supported. For an optimal experience visit our site on another browser.

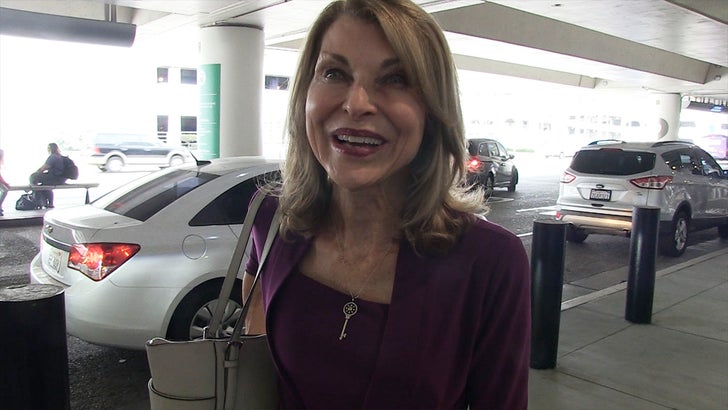

My Son, the Sex Offender: One Mother's Mission to Fight the Law

Sharie Keil helps lead a shame-free alliance of sex offenders and their families, supported by researchers who see registries as a "failed policy."

May 7, 2014, 6:56 AM MSK / Updated May 8, 2014, 1:00 PM MSK

In the run up to Halloween one year, Sharie Keil saw something that really made her jump: Missouri governor Jay Nixon, then the attorney general.

He was on television to announce that registered sex offenders were hereby banned from participating in her favorite holiday. On threat of a year in jail, they had to stay inside and display a sign saying they had no candy. The goal was “to protect our children,” as Nixon put it, but Keil heard only a peal of political hysteria.

She is not a sex offender nor, at 63, a new-age apologist for pedophiles or predators. She is a mother, however, and in 1998 her 17-year-old son had sex with a pre-teen girl at a party. He was convicted of aggravated sexual abuse, which got him six months in county jail and a lifetime of mandatory registration as a sex offender. Ten years later, after the Halloween law, Keil felt shocked into action.

”As my husband says, I decided to go on the war path,” she remembers.

Today, she’s at the forefront of a growing fight against sex offender registries, a shame-free alliance of offenders and their families, supported by researchers and some advocates who helped pass stringent anti-abuse laws in the first place. They’re organized (albeit loosely) under Reform Sex Offender Laws, a five-year-old lobby that claims 38 state affiliates and a steady patter of legal and legislative victories.

Most of their progress, however, has been limited to a slice of the registry: juvenile offenders. That would remove Keil’s son, but this former soccer mom and chapter head of the League of Women Voters wants to abolish the public registry altogether. She funds a powerful RSOL affiliate, Missouri Citizens for Reform, which has helped push sweeping changes through the Missouri House four years in a row, only to see the effort smothered in the Senate or, last summer, stabbed by a governor’s veto.

“Changing the registry would provide relief for tens of thousands of Missourians,” Keil says. “Since there are nearly 800,000 people on the registry nationally, millions of lives would change for the better.”

As reckless as Keil’s ideas may sound, she and her intellectual allies—among them Nicole Pittman, an attorney who slammed registries in a Human Rights Watch report last year—are fervently opposed to sexual abuse and believe in jail time for law breakers. However, they also hope to realign the law with second-chance ideals and new research that shows rehabilitation is possible, even for America’s last pariahs.

If they succeed, Keil believes, public safety will actually improve. As the registries shrink or disappear, law enforcement will be freed to focus on crime prevention. If the movement fails, she warns, public safety could suffer. Truly dangerous people will be lost in the thousands that police must monitor, while relatively harmless offenders break bad in a system that gives them no hope for a normal future.

“We’re all in the soup,” Keil says, using one of her favorite metaphors for describing the way the registry absorbs all offenders, undifferentiated by risk. “They throw it over everyone, and it’s like being in a quagmire. You can’t lift your legs high enough to get out.”

“We need to forget everything we think we know about sex offenders, because 20 years of research has shown us it’s all pretty much wrong.”

To victims’ advocates, of course, that’s precisely the idea. For years many have lobbied to apply the term “sex offender” to a broad cross section of juveniles and adults, flashers and rapists. The rationale is that sex offenders are incurable, insatiable, and psychologically the same. Under federal law, for example, a Jerry Sandusky-type will be on the registry—and so will a 14-year-old whose hand wandered under the knickers of an 11-year-old sibling. Under Missouri law, Keil’s son got the same registry requirements as a violent attacker.

Since 1994, when Congress first required sex offender registries, the population on the rolls has doubled and doubled again. “It seems to make sense, doesn't it?” said President George W. Bush, moments before signing the Sex Offender Registry and Notification Act of 2006, which expanded registration to nonviolent crimes like indecent exposure and public urination. Scott Berkowitz, president of RAINN, the country’s largest anti-sexual assault organization, called it “a landmark bill…that’s going to make a real difference.”

Keil wants to shatter this mindset. Over the years, her family and affiliated businesses have sunk more than a quarter million dollars into Missouri politics, including tens of thousands of dollars related to sex offender reform. That kind of money opens doors and Keil has hired a lobbyist to walk through each one. She wants to win with data, not emotion. And last year it seemed she had.

The Missouri legislature passed a law that would remove juveniles from the registry, making it the first state to vote its way out of compliance with federal law (others have yet to vote their way into compliance). Keil saw it as a first step to broader reform. But Nixon vetoed the bill last July.

Now Keil is hoping to hit back by telling her personal story for the first time. After the veto, the Associated Press revealed Sharie’s lobbying role and published her husband’s name and primary business. Fearing vigilantism, she requested that NBC not repeat those names or the name of her hometown.

With those conditions met, she welcomed a meeting in a gazebo on her ranch south of St. Louis, where she explained what the governor—and everybody else—needs to do when it comes to sex crimes.

“We need to forget everything we think we know about sex offenders,” she says, “because 20 years of research has shown us it’s all pretty much wrong.”

“We've cast such a broad net that we're catching a lot of juveniles who did something stupid.”

In the aftermath of her son’s conviction, Keil felt “smashed to the floor” by the requirements of his sentence. The weekly probation meetings. The mandatory therapy. Slip ups could mean jail time. What if he got a flat tire near a park? What if he pulled into a school parking lot to use a pay phone?

“It felt harder to stay out of trouble than is even possible,” she says.

Sex offenders have come to face a medieval series of possible fates, including chemical castration, civil commitment, and, most commonly, a lifetime on the move. They jump from apartment to apartment, job to job, pushed out as employers and landlords discover their public records—and point to the door. Today, if the registry were a city, it would have more people than Boston and Halloween would be the least of its problems.

But hold on a minute, Keil thought: does any of this actually help public safety?

She found part of her answer in the form of Mary Duval, another mother of a registered sex offender. Duval’s son was 16 when he slept with a 13-year-old he had met at a club for older teens. After his conviction for sexual abuse, he had “sex offender” stamped on his license and couldn’t go to his brother’s football games. Duval decided to fight it, inspiring Keil to do the same.

“I was so desperate,” Keil remembers of meeting Duval at a gas station in map-dot Oklahoma. The women couldn’t have been more different. Duval was blind and rural. Keil is a city girl, the daughter of a fashion designer who had the Johnny Carson line of outerwear. But after Duval died of cancer in 2011, Keil felt she was inheriting the fight.

She clutched a summary of her position as she spoke in the gazebo, the paper shaking slightly as she made her points, all based on recent academic research.

Sex offender laws developed in response to a seemingly widening crisis of childhood sexual abuse in America. In fact, the rate of sexual crime involving children has been falling for at least two decades, according to David Finkelhor, Ph.D., director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center. The steepest declines came before the spread of registries, he adds, and the drop has continued even as more sex crimes are being reported.

It’s still a problem. The National Crime Victimization Survey reported 346,830 rapes and sexual assaults against people aged 12 and over in 2012, the latest year available. In years past, about a fifth of those cases involved victims between 12 and 19 years old. The Department of Justice says that as many as one in three girls, and one in five boys will be sexually abused by the time they reach 18. That’s a tragedy, Keil is quick to admit, but unfortunately, she says, sex offender registries are not a solution.

They’re based on the idea that if you know who the dangerous people are, you’ll know who to avoid. But 93 percent of sexually abused children are not violated by a lurking stranger, according to government data: They know their assailant. The bulk of the remaining seven percent of crimes are not committed by people on the registry. In fact, the recidivism rate for registered sex offenders is lower than any crime other than capital murder, and not because of the registries themselves, according to study after study.

“These policies don’t work,” says Elizabeth Letourneau, Ph.D, director of the Center for the Prevention of Child Abuse at Johns Hopkins University. She recently reviewed 20 studies of registry laws and found that 18 showed no reduction in repeat offenses. “When you have 20 studies that fail to support your policy, you have a failed policy,” she continued.

Pittman, who spent 16 months studying registry laws for Human Rights Watch, called the laws “overbroad,” “misconceived,” and “devastating,” particularly for juvenile offenders. Now she has come to a new conclusion: abolishing the rolls entirely. “We’re going in the wrong direction,” she says, noting that America is the only country in the world with a public sex offender registry. “We’re going to a police state kind of model.”

But perhaps the most surprising convert to the idea of abolishing registries is Patty Wetterling. After her young son Jacob was abducted by a masked man in 1989, Wetterling helped Congress pass the first federal sex offender registry law. Today, she’s board chair of the National Center for Exploited and Missing Children, an organization that supports current law. She used to agree, but today, she can sound a lot like Keil.

"I'm a fan of reform," Wetterling said in an email. She leans toward the view that only law enforcement should have access to registries and only genuinely dangerous people—as determined by doctors—should be on them.

“We've cast such a broad net that we're catching a lot of juveniles who did something stupid or different types of offenders who just screwed up,” Wetterling told a Minnesota newspaper last year. “They are very different from the man who took Jacob.”

Keil is thrilled with such dramatic shifts in opinion, but she’s also at a loss regarding the politics. As Missouri legislators break for summer campaigning, she’s hoping to build momentum toward a new push for her juvenile reform bill this fall. So far, it looks unlikely that Nixon will sign her bill as written.

A day after the gazebo meeting, Keil met a friend named Pamela Dorsey, a fellow activist whose son landed on the registry at 18. He was charged with possession of child pornography—an old download, Dorsey says, part of a torrent of images he ripped from a file sharing service some four summers before, when he was 14. One of the files had been tagged by federal agents, who showed with the morning sun in January 2010.

That July, Dorsey’s son plead guilty and got 40 years of probation along with a lifetime on the registry. As he learned what registration meant, and what it did to the way people saw him, this clean-living, former choir-boy turned to heroin for relief, his mother believes. By November he was dead of an overdose.

But that’s not what haunts Dorsey the most.

“His death has not traumatized me as much as what he went through before he died,” she says, clutching a framed photo of her son. “It’s horrifying, it’s insanity, and it’s wrong.”

Be the first to know about breaking news and other NBC News reports.

This site is protected by recaptcha Privacy Policy | Terms of Service

WE AND OUR PARTNERS USE COOKIES ON THIS SITE TO IMPROVE OUR SERVICE, PERFORM ANALYTICS, PERSONALIZE ADVERTISING, MEASURE ADVERTISING PERFORMANCE, AND REMEMBER WEBSITE PREFERENCES. BY USING THE SITE, YOU CONSENT TO THESE COOKIES. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON COOKIES INCLUDING HOW TO MANAGE YOUR CONSENT VISIT OUR COOKIE POLICY.

We'll notify you here with news about

Turn on desktop notifications for breaking stories about interest?

Mother-son incest victim describes shame, and redemption through his son.

Dec. 1, 2009— -- The molestation began as gentle fondling when Gregg Milligan was 4 years old, but it soon escalated to aggressive touching and eventually beatings that would render him unconscious.

For seven years, until Michigan child welfare workers intervened when he was 11, Milligan was too ashamed to reveal that his tormentor was his own mother.

"She was very brutal," said Milligan. "Through her difficulty reaching climax, she would become frustrated and violent, hitting and punching and slapping not only my genitals, but my face and body."

"It was terribly confusing, and it wasn't just the violation," said Milligan, now 46, and director of infrastructure for a major health care provider in Michigan.

As bad as the incest was, things got worse. Milligan's father had left when he was 2, but by the time he was 8, his mother, an alcoholic and a prostitute, invited strange men home who would sexually abuse him.

"Back then I would never tell anyone, not even a sibling," said Milligan, the most "compliant and sensitive" of three children living at home. "I was just too afraid. It was so horrendous for me to believe she actually would do this to me."

One of the unspeakable secrets in the world of child sexual abuse is that mothers can be molesters. Often, they prey on daughters, but more frequently their sons -- who report increased feelings of isolation and sexual confusion along with thoughts of suicide.

Both of Milligan's parents are now dead, but his past still haunts him.

"Around 10 years old, I started to get this unbelievable feeling of dread that if I don't get out I am going to die from the decadence, the debauchery, the forced molestations and the beatings that became more severe," he said. "For three months I suffered from hysterical paralysis."

An estimated one in four girls and one in seven boys will be sexually assaulted or abused before the age of 18, according to the Alabama-based National Children's Advocacy Center . In 27 percent of these cases, the abuse is perpetrated by the child's parents.

Previous studies of day care workers published in 2000 in the Journal of Sex Research, found that women -- without male accomplices -- accounted for only about 6 percent of the abuse of females and 14 percent of males.

But more recent national surveys indicate about 12 percent of all child abuse cases are committed by women -- "a 100 percent increase compared with previous data," according to Chris Newlin, NCAC's executive director.

"We view females as care givers and protectors of children," he told ABCNews.com. "Now we are beginning to understand females are sexually abusing children, and it is occurring much more."

Professionals are stymied by public perception that incest is "an ugly subject," and that women can't commit such crimes.

"If it's a 35-year-old female and a 14-year-old boy, we'd say the boy is getting lucky," said Newlin. "And if it was a 35 year-old male and a 14-year-old girl, we'd call that a pervert."

And boys like Milligan aren't often believed.

"We have this overarching thing that goes back to the Salem witch trials of children making up stories," said Newlin. "You can't trust kids."

Survivors like Milligan say that these crimes often go unnoticed, not just because society can't imagine women as aggressors, but because boys feel riddled with shame.

"There is this terrible stigma that boys crave sex," said Milligan. "We are just as impressionable and naive and just as afraid. How can anything be consensual at 4 or 11 years old?"

He was finally able to tell all in the self-published memoir he took a decade to write -- initially titled "God Must Be Sleeping," he changed the title to reflect a more upbeat chronicle of his survival, "A Beautiful World."

But Milligan has much to be positive about. Though his childhood was ravaged, he has managed to raise a son, now 23, who "has never known violence or abuse."

Today, Milligan is a spokesman for the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, sharing his experiences as a survivor.

About 10 percent of all crisis calls to the RAINN hotline are from males, according to program director Jennifer Wilson, who said they get about 100,000 calls a year.

"This crime is hard to track because people just don't share it with law enforcement," she told ABCNews.com.

In September, when child star MacKenzie Phillips went on the "Oprah Winfrey Show" to disclose her father had raped her at the age of 19, calls to RAINN's hotline from incest victims "spiked."

Mothers who sexually abuse tend to have higher rates of mental illness and are often the victims of abuse themselves. They also have easier access to children.

"It's easy for women to go unnoticed," said Wilson. "And at the legal stage, they get lighter sentences."

Because incest is considered taboo, few boys come forward and social service providers are not often trained in detecting signs in women abusers.

One victim, Dominic Carter, a TV news reporter in New York, wrote about his own abuse at the hands of his mother in his 2007 memoir, "No Momma's Boy." Earlier this month, Carter was convicted of attempted assault after a 2008 fight with his wife, and could face up to three months in jail.

As a child, Milligan turned his anguish inward.

"My brother and sister could leave the house and naturally play with friends," he said. "I was petrified to leave mother. The clear sense was that if I did, the punishment would be worse."

His mother also threatened to kill herself and Milligan said he more than once was hit by cars while chasing his mother into the street.

His father was equally volatile, returning once to beat his mother "so bad he left her with an eye hanging out of the socket."

Teachers were also unaware of the abuse. "In their defense, I was kept out of school," he said about his frequent injuries. "My mother was very cunning."

The family was on welfare, but when social service

Watch Sbnr 203 Jav Video

Super Skinny Anorexic Porn

Private Key Encryption

Wife Masturbation Hidden Camera

Japanese Squirting Multiple Orgasms

Sex Talk Makes Mother and Son Game Super Awkward on ‘The ...

My Son, the Sex Offender: One Mother's Mission to Fight ...

Real Wrestling - Mom and son fight part 1 & anne ve oğul ...

Mother-Son Incest: Hidden in Shame and Rising - ABC News

“Mother!” and “Battle of the Sexes” | The New Yorker

Mum who had sexual relations with 'persistent' son, 15, is ...

Alabama mom 'photographed sex acts with her children ...

Mother and Son - IMDb

Mom Denies Oral Sex Claim by Teen Boy Video - ABC News

Woman sentenced for having sex with foster son

Mom And Son Sexual Game Battle