A Survey of Totschläger: a saintslayer’s songbook by Abigor. Chapter II: design, type, typography

The Old Conception of Black MetalSuperscripts⁶⁶⁶ and a glossary of words marked bold in the text → https://telegra.ph/footnotes-and-glossary-totschlaeger-chapter-II-03-09

This chapter is full of (at first glance) seemingly irrelevant information, but I did my best to remove what doesn’t add to the puzzle. In brief, everything here is interconnected.

Instead of epigraph

If blood must be spilled, blood will be spilled.— the album press-release

Typography may be defined as the craft of rightly disposing printing material in accordance with specific purpose; of so arranging the letters, distributing the space and controlling the type as to aid to the maximum of reader’s comprehension of the text.— Stanley Morison (1930)¹

Typografie ist die Inszenierung einer Mitteilung in der Fläche.— Günther Gerhard Lange (no later than 2011)²

…by a Typographer, I mean ſuch a one, who by his own Judgement, from ſolid reaſoning with himſelf, can either perform, or direct others to perform from the beginning to the end, all the Handy-works and Phyſical Operations relating to Typographie.— Joseph Moxon (1683)³

Typist is a person who types, a clerical worker who writes letters, etc., using a typewriter.— Wikipedia

Introduction

Totschläger press-release stresses the quality of the physical product twice:

Both formats [hardcover mediabook CD, or the gatefold LP] have been laboriously prepared to do the content justice, neither LP nor CD are standard quality, neither trouble nor expense has been spared for this cornerstone release. […] Neither CD nor LP are standard products but items of the highest quality, from booklet paper over mediabook CD to the vinyl lacquer cut.

Matching these words with the end-products — the LP and CD variants — challenges the word laboriously. What does the press-release mean: diligently or time-consuming? If the former, then a few objections are well-deserved since the amount of imperfections in the design, though not much, is just enough to be noticeable.

In a Bardo Methodology interview TT speaks of his early experience in music design, and of his relations with computers in this context:

I touched a computer for the first time at the turn of the millennium. I just got the physical stuff like photos and paintings and cut-out images from Napalm and then brought it to the layout companies in Vienna. This was in times before everyone was a Photoshop wizard and labels had to use horribly expensive layout agencies. For the ABIGOR debut, Verwüstung/Invoke the Dark Age (1994), we handcrafted the fold-out booklet complete with rub-letter text and pasted images. We did the same with our demo covers, handmade and printed at a copy-shop. At least the layout guy managed to persuade me to re-type the text with computer font, because at first I insisted that he just scan the handmade booklet, to be printed exactly the way it was.⁴

It’s a curious recollection. Many years have passed since…, whilst something in the common design of black metal, Totschläger being no exception, still begs to be buried by time and dust. And you know its name — Naïvety, which (the longer it wanders aimlessly) mutates to Stupidity.

The persona(e) chosen to conduct and fulfill the album design (are they the “Photoshop wizards?”) displayed a scant knowledge of the intricacies of typography, a lack of critical thinking, of questioning, and of any grounded taste. Surely their idea of quality attempts to destroy — and mercilessly so — the one which governs Abigor’s approach to music and its production. Thus, even though Totschläger is an undeniable, ideal masterpiece of art and a truly cornerstone release, the work as a whole appears contradictory. And it is exactly its design that pulls the album back. Indeed, the album carries its design like a burden, instead of them altogether pushing the (c)art forward, no thing overshadowing the other.

This remains strikingly obvious even taking into consideration an important but simple fact: it is impossible to fairly judge all the aspects of design with full certainty without having been involved in the process (myself). Design is the planning and drawing of something before it is made,⁵ and what I have at hand is only the end product. Still, being confident the designers (whoever they were) got no fucking guns against their heads, the results of some of their choices are liable to a fair autopsy.

The stance from which I write is the understanding that what the Typography Fathers say is true until proven opposite. I write for the benefit of the admired arts and crafts (Abigor, black metal, typography), of those who connect them and who are connected by them. Totschläger design, as well as the design of many other black metal records, deserved proper editing supervision, which it had not received. So may it be my input into the scene displaying what simple steps can be done to raise the level of consideration to proper. These notes are a result of professional perception, written down with a specific didactic goal: that such detailed comments, besides other things, would help designers to develop a beneficial ability to describe graphical things (and what they want) with words and numbers. In a craft like typography, no matter how perfectly honed one’s instincts are, it is useful to be able to calculate answers exactly.⁶

(with Mercy)

The shape of an album shall be perceived as a constitution of parts or aspects, each of which had its individual development within (and to form) the complete entity.

Some formats, such as the booklets that accompany compact discs, are condemned to especially rigid restrictions of size. Predefined, thus rarely disputed, are the shape, size and capacities of the media e.g. the 12-inch vinyl or the CD format; the size and capacity of the gatefold (approx. 12½ inches), double-square, etc. Those are permanent external forces — aspects to accept. So we don’t question them.

Within the shape there are unpredetermined, “variable” traits whose final appearance, Inszenierung in der Fläche, manifest under conduct of the designers. In case of Totschläger those are the following, in no particular order:

- The choice of cover artwork;

- Assignation of script or type for everything written;

- Gatefold outer design, including positioning of the artwork, typography, putting the record label logo, etc. — the visible presentation of the album;

- Gatefold inner design, including photography, illustrations (the sword, the “frame” of the photograph), setting the verse from “Orkblut (Sieg oder Tod),” etc. — the hidden presentation of the album;

- The choice of illustrations in the booklet;

- Booklet design and typography;

- Vinyl disc label design, and others…

Let’s recall again TT’s words (quoted before in Chapter I) from the Invisible Oranges interview:

There should be coherence, ultimately a golden thread running through all the aspects that make an album. Ideally there’s unity, formed by the lyrics and the visual part, by the sound, language, mastering, band pictures, everything has a certain task. As opposed to other artforms, in black metal this is vital for the work…⁷

The designers’ task was to conduct, to design the interaction between the visual aspects in order they support a coherent presentation of the album. The outcome nourishes the reflection that the band wished the designers would conduct a marriage of deadly adversaries: craft and industrial product.⁸ Despite the mass-production nature of audio records as goods (with, theoretically, a fractional exception within the tradition of demo-tapes as we know them in the underground), the desire to preserve the spirit of craft at least partially is on the surface. It seems, what skipped from the collective is the understanding that the products of craft are essentially handmade, and that any attempt to deliver a “craftsy” mass-product is doomed to failure.

If the concept of Totschläger essentially demanded a relation to craft, one of the better ways to solve the problem could be, first, to factually design it with the methods of craft, liberated from mass-production traits like the use of industrial (computer) typefaces, digital typesetting, digital scaling of images etc., and, second, to deliver it to the worldwide consumer as a reproduction e.g. in the vein of the books of artwork reproductions. Although, even this might’ve been a palliative.

Artwork

The artwork was described in Chapter I in as much detail as appeared possible back then, and there still is not much to add. Missing there was a better explanation of the scenery which, it is clearer now, depicts the place called Caina — after Cain, patron of the album. The name was given by Dante to the first of the four divisions of Circle IX of Hell, where Traitors are punished.⁹

Gatefold

Unpack the parcel from W. T. C., notice the difference in sharpness between the band logo and the image to the left:

It is confusing. Notice that the crown of thorns is the only area in the artwork which appears in lower resolution or out of focus. Other parts are unexplainably sharper. Can it be that the crown was not present in the original painting and was “photoshopped” into the image? A casual photograph posted by TT, maybe containing the original painting, hides that part and there may be a reason for that.

The folding of the gatefold is so inexact that it indeed makes the production quality stand out from many other similar products.

A photograph on discogs shows the same signs of bad folding, thus it’s an issue with at least several copies if not the whole pressing.

There is no text on the binding edge:

It is a good idea: the binding edge needs no additional information since the artwork is memorable, the album is immediately recognizable when on a shelf among other records. But if text was there, the band logo and the album title could be removed from the cover, which would’ve been another, even a better idea. (Explained further.)

Сhoice of typefaces

Keeping a low profile of the “stage-designer,” being restrained by alphabets, writing systems, orthography and typesetting rules, by peculiarities of the text original, a typographer converts one graphic production — a manuscript, for example — into a more perfect reproduction. Typography serves the reading, and usually fulfills its duty rather unnoticeably.¹⁰ Typeface selection is often based on a textual genre: a popular impression is that subject plays a role, that a romantic novel requires a romantic looking typeface or a mathematical work an exact looking one.¹¹ Personal preferences naturally play a part in making these choices, too.

Normally, readers notice typography only when stumbling upon display face constructions, logos, type illustrations, and other things made with the prescription to persuade, to stimulate reading, to satisfy aesthetic needs.¹²

When it comes to metal music, employing the gebrochene Schriften — “broken scripts” altogether called blackletter — is an old tradition. Abigor, for example, followed it in the designs of most of their albums (including their older logo). We may conclude that the employment of blackletter in black metal design is already an aesthetic need of the scene.

What is a worthy typographer conscious about? That design makes us orientate on the basis of its associated meanings, that a chosen typeface would often saddle numerous meanings. The Totschläger case has traits of clear historic allegiances. But the musical and thematic contents of the album are less dependent on them. Hence arises a number of exercises:

- to set in different languages i.e. multilingual setting — to set texts in English, one title in French, and a few cases in German which are the album main title, two song titles, and fifteen lyric lines in the song “Orkblut (Sieg oder Tod)”;

- to highlight a few purely German events amidst the multilingual setting by means of the national typographic tradition (i.e. choice of Fraktur);

- to understand that digital typesetting, manual typesetting and handwriting are all different technologies.

In case the typographer has time restrictions, or lacks experience with old fonts, the first two exercises could be basically more-or-less passed by choosing a typeface (or two) without any clear historic allegiance. (For example a blackletter from the twentieth century, like Goudy Text which had been already used by Abigor in the past — some slightly modified version of it appears in the design of Leytmotif Luzifer.)

The third exercise is more difficult because it demands a designer bestowed with curiosity, privileged to contemplate — such is a rare species, and is not our case. Thus we witness that the album’s typographic tasks were solved within the computer/Internet paradigm, not within that of traditional pre-computer designs. The designers’ twenty-first century display monitor vision is way too far from the asserted traditions. But wasn’t it the link to crafts and manual work which was supposed to bind the album design?

Typefaces chosen

In the babylonian mixture of scripts used in the design a combination of two is primary: lyrics, tracklist, album subtitle are set in script typeface, while the album title and song titles in the lyric pages are set in Fraktur, the German Renaissance blackletter. Though the press-release does link to the ’80s influences, I’m inclined to think the coincidence is accidental that this combination brings up the memories of Under Jolly Roger by Running Wild, from which you may see the lyric-sheet below:

1520s: Cöllnisch Current-Fractur

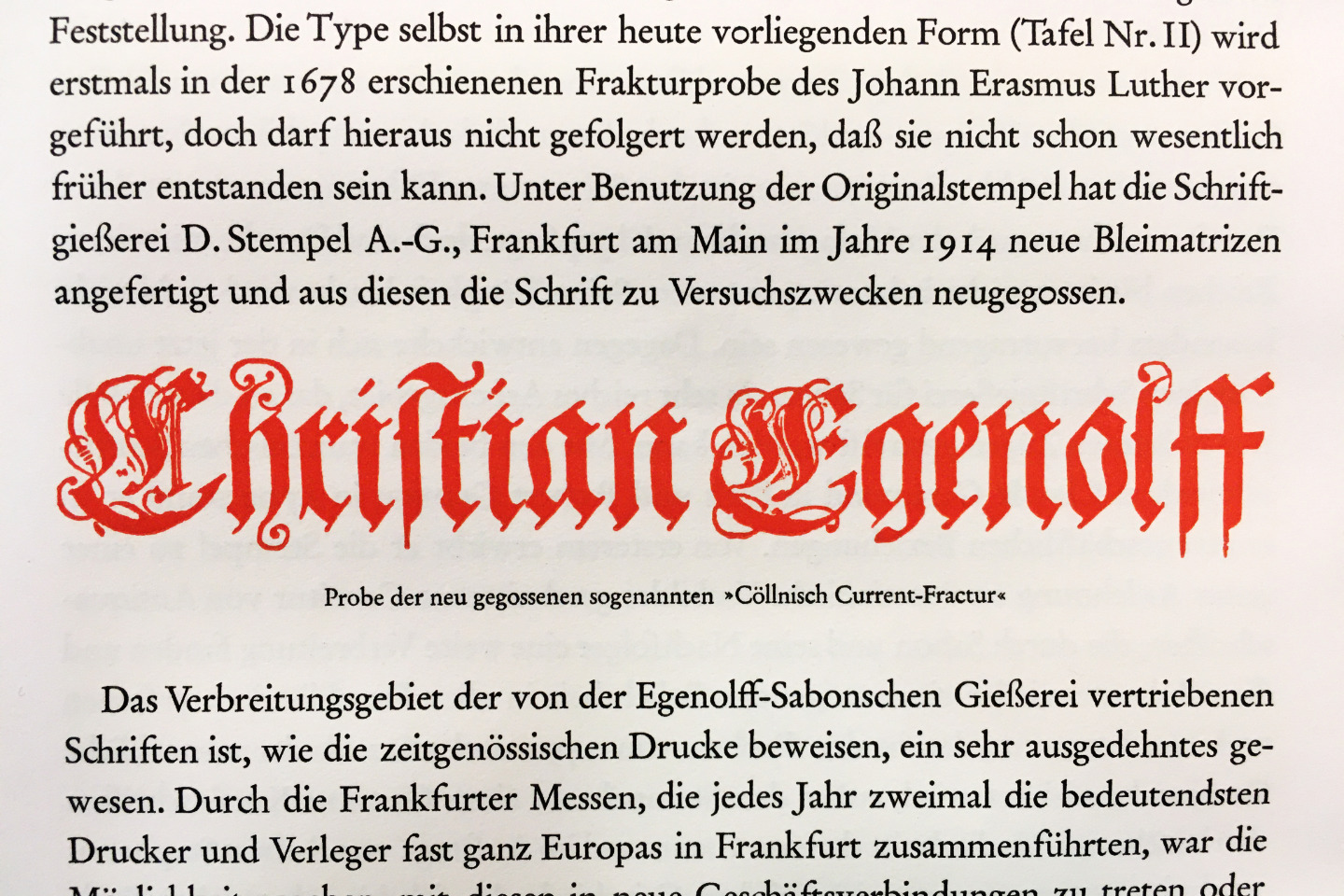

The song titles in the lyric pages in the booklet, and the album main title on the cover and in the booklet — are set in Coelnische Current Pro, a digital typeface released by SoftMaker in 2000 as a part of Elegant Blackletter Fonts bundle.

If the title of the bundle, Elegant Blackletter Fonts, makes you think there’s anything elegant about it, think again. Because this digital version of the beautiful old font, as well as the whole bundle, is shit, a true rip-off for the naïve.

Searching for this Fraktur origins and past usage I stumbled upon Dr. Daniel Reynolds’s article in which he shows a type specimen stored in the Library of the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz. I visited the library in order to witness the print myself.

Unluckily, the library staff could not find the copy of the specimen photographed by Dan Reynolds for his article, and only could provide recent photocopies of another copy of that specimen which is stored in the University Library in Frankfurt. I went to Frankfurt to see the original print, but getting into the reading halls turned out to be so complicated, like everything in Germany, that I still haven’t managed to hold any original prints in my hands, and instead studied scans and photocopies.

Albert Kapr writes:

It is reported that Christian Egenolff, the founder of the Luthersche foundry in Frankfurt, began casting the Cöllnisch-Current-Fraktur in 1524 with borrowed matrices. In 1952, Jan Tschichold wrote in his Treasury of Alphabets and Lettering: “The stamps of this beautiful old German typeface from the end of the 16th century have been preserved (only to the degree shown) and are a valuable possession of the type foundry D. Stempel AG. in Frankfurt am Main. But the font is no longer cast. To my knowledge, the alphabet has never been printed.¹³

Following Kapr’s reference I opened the second edition of Tschichold’s Meisterbuch der Schrift and found not a single mention of the font, to say nothing about him displaying any samples of it. There still is a slight possibility that Tschichold did mention it in the first edition of the book, but I’ve no access to it at the moment.

Tschichold does show the font which can be seen in the specimen above as the Gros Canon. He calls it großer Frakturgrad aus Leonhart Fuchs’ «Kreüterbuch», gedruckt von Michael Isingrin, Basel, 1543, but most probably this font is also of a slightly older age, because Christian Egenolff used it in his books in 1530s (if my memory doesn’t fail me yet).

What is important about this particular font is that it was obviously very popular among German printers and for a long while (its popularity did not fade for at least 50 years) and many books are set in it. The uppercase letters (not the initials!) from it are seen on the title page of the German edition of De prӕstigiis dӕmonvm, published in 1584 by Nikolaus Bassée in Frankfurt. The lowercase are from a different font though, or they are a later modification of the original font.

For a brief moment I suspected that Abigor members were aware of that particular edition, and it was the book which made them look for a font from the sixteenth century. It was a wrong assumption, but we still will return to this book later.

As it is clear now Coelnische Current Pro is a digital revival of the font seen in the first line in the specimen, size Gros Sabon, named Cöllnisch Current-Fractur in the (other) sources.

We don’t know if Kapr saw the specimen, but we can be sure he studied literature which told¹⁴ the story of the type. Probably, for the reproduction in his book he received smoke proofs of the type from D. Stempel AG or made them himself upon a visit to the type-foundry.

We can also be sure that SoftMaker had the pages from Kapr’s book as their only, single source for the digital revival. Such limited conditions aren’t at all enough for the creation of any faithful revival of any font. Moreover, to use such digital garbage in (almost) any project is beyond comprehension. If a portion of curiosity is present in a typographer she wishes to know at least minimum about the tools she uses, and the information is to be found in the closest fucking library.

The Internet is a great invention for those who know what to do with it. If you’re not banned on Google you may find historical prints made with Cöllnisch Current-Fraktur — some date earlier than the 1678 specimen. The Viennese are even luckier. Assuming the designers of Totschläger visit Vienna at least sometimes, it costs them no more than a walk to the well-known establishment in Josephplatz 1 to hold such precious prints in their own hands. One (1596–8), two (1597), three (1597), four (1604), five (1618), six (1624) — and the earthly existence becomes a little less ignorant and after such a costless experience responsible typographers would never use the cheap crap like SoftMaker’s. But only if they acknowledge their responsibility to push the art at least not too far behind from where the musical and conceptual components developed to in the past decades. Black metal is no longer in the cradle, but its design definitely resembles scribbling of a child — and after all those years we can be sure this 30–40 year-old child is retarded. Possibly beyond rescue.

A few things are exceptionally bad about the digital revival:

- lowercase letters are scaled at approximately 93% size of the original (see x-height), as if the guys from SoftMaker know type design better than the punchcutters of the sixteenth century. Such an event is enough to kick them out of the profession.

- the umlaut is designed absolutely wrong and, sadly enough, it now “shines” on the album cover just as shown right above. The common German convention now is the double dot (¨). In German blackletter it could have that form, or the form of small breve, or inverted breve (Gutenberg Bible), or of thin short diagonal strokes — I know no example older than a century in which the strokes are notably long.

Historically, another convention co-existed together with the double dot — a small letter e installed above the main letter. Such was the only form of umlaut in Cöllnisch Current-Fraktur in the lowercase ä, ö, and ü. Any faithful revival of the font shall reflect it.

For its “modernized” umlaut SoftMaker could use the strokes as in i and j in the original font, and adjust them for the umlaut. Instead they designed a Hungarian double acute or long umlaut (˝ instead of ¨) which does not even exist in German orthography. They added e above as an alternate, but a foreign one: copy-pasted the e from another of their revivals in the Elegant BlackLetter bundle, Wilhelm Gotisch Pro typeface, which is their version of Wilhelm-Klingspor-Schrift. The latter is a blackletter from a different class: it’s a Textura, not a Fraktur. Compare the historical glyph in metal (mirrored), and on paper, with their alternate a-umlaut. Their solution appears obviously stupid.

(Wilhelm-Klingspor-Schrift is known to black metal by the logo of Gorgoroth; Marduk used it in their designs, the Black Metal Endsieg split was designed with it — to name a few. The typeface was created in 1920–26, and is 400 years younger than Cöllnisch Current-Fractur.)

- The original Cöllnisch Current-Fractur has no parentheses because at the time of its creation parentheses were used only when setting in Roman type. SoftMaker played the same trick — copy-pasted the parentheses from Wilhelm Gotisch Pro, and we can witness this foreign element in the setting of the title “Orkblut (Sieg oder Tod)”. But the parentheses of the Renaissance and early Baroque were pure line — curved rules, with no variation in weight. Thus we witness a double-fake:

- Dozens of symbols in this digital revival have nothing to do with the original. Ligatures are fake and irrelevant, the figures (titling they are, an invention of the nineteenth century!) are copied from Wilhelm Gotisch Pro again. Not only umlaut, but all diacritics are a disaster.

- Kerning is uninformed. Compare the setting of Scarlet and Suite on the respective page in the booklet, then see Nightside and Eligos. The setting of the “Nightside Rebellion” title is a rebellion in itself.

- et cetera.

Good, some enthusiasts from minor type foundries can rip-off whoever they wish, let’s not even judge them. What’s lame is the irresponsible service of those enrolled to secure and control that the greatest band is visually presented the best way. Do they really allow themselves to be ripped-off by minors?

What is blackletter to German culture? Let’s read from Goethe’s mother in a letter to her son:

A word only in regard to our conversation during thy stay here about the Latin letters. [i.e., about Antiqua] The injury they will do mankind I will make palpably plain to thee. They are like a pleasure-garden belonging to the aristocracy, which no one may enter but the nobility and people with stars and orders; our German letters are like the Prater at Vienna, over which the Emperor Joseph had written, For All. Had thy writings been printed with these odious aristocrats, they would not, with all their excellence, have become so universal. Tailors, seamstresses, maid-servants, all read them; each finds something adapted to his feelings, and thus they walk in the Prater pellmell with the Literary Gazette. Doctor Hufnagel and others enjoy themselves, bless the author, and hurrah for him! How wrong Hufeland has done to have his excellent book printed in letters of no service to the greater portion of mankind. Are only people of position to be enlightened? Shall the lowly be shut out from everything good? And this they will be, if a check be not put to these new-fashioned grimaces. From thee, my dear son, I hope I may never come to see any production so adverse to the interests of mankind.¹⁵

I assume Fraktur did not appear in the album design by accident, and here I’m referring not exclusively to the traditions of metal music design. “The odium of the Deutschnationale (German National) clings to blackletter”,¹⁶ “retaining Fraktur is perceived abroad as chauvinism, it is repulsive as arrogance”¹⁷ — and the use of Fraktur in Totschläger serves the correct presentation of the military themes expressed with German words (thus, by association for a non-German listener, nationalistic at the very least) “Sieg oder Tod” and “Kommando”. The album was published by W. T. C. — a record label run by Sven Zimper of Absurd, the band which has in its history a notable allegiance with NS. More than that, at least one riff — in “Terrorkommando Eligos” — is quoted from an Absurd song “Heidenwut” (heathen wrath) from Blutgericht album. Which else evidence is needed to acknowledge the links between Totschläger and the (art which deals with the) part of human history marked by participation of the German military and the NS?

Maybe, though I’ve no proof, the choir which sings the line “Sieg oder Tod” includes musicians associated with the NS scene — it won’t come as a surprise if true. Abigor is “Black-Metal Exclusively,” stated on their facebook page, and the history and essential understanding of black metal is unimaginable without acknowledging that it knows no maximum level of acceptable atrocities. The album’s bridges towards the German military can also be seen as a sign of support to the distinguished veterans within the scene who had been troubled in the recent years by activists for their past expressed appreciation of the NS ideas, or connections with members of the scene who had ever expressed such appreciation.

Another (maybe unconscious) reason to choose Fraktur is the fate of the script. The Gutenberg Bible was set in Textura — the precursor of Fraktur. And it is Fraktur with which the most influential German translation of the Bible — the Luther Bible — was printed for centuries. Fraktur is the face for probably all the liturgical publications in the German language for centuries.

The rise of Fraktur as the preferable script for the Bible in German was, of course, more than a turn of fashion. The glow of holiness was reflected onto it: whoever, as a child, read the Catechism set in Fraktur and later studied the Bible in it, and then sung from the hymnal in it, transmitted the qualities of those texts to the form of the script. Fraktur became his native evangelical script.¹⁸

An evangelical script!

In 1793 or 94 a German publisher Friedrich Justin Bertuch, who was pro Antiqua in the Antiqua–Fraktur dispute, called blackletter “an ugly script of monks.”¹⁹ — Script of monks! Thus its associations with religious writings of the German-speaking lands does perfectly fit black metal in the German speaking countries, because black metal is a spiritual event.

1776–1823: United States Declaration of Independence

American Scribe, released by Three Islands Press in 2003, is a script typeface (i.e. designed to imitate a handwriting), and is the most used face along the Totschläger layout. It appears on the cover in the album subtitle “a saintslayer’s songbook”; the tracklist on the rear cover, the lyrics and tracklist in the booklet, are all set in American Scribe. This typeface may be tolerable in the shortest messages but reveals its flaws in longer runs of texts.

In a few previous writings I stated the typeface originated in the penmanship of Timothy Matlack who was, as wikipedia tells, “known for his excellent penmanship and was chosen to inscribe the original United States Declaration of Independence on vellum.” My words were founded on the description provided by the type foundry, which says:

In 1776, when the Continental Congress ordered the Declaration to be “fairly engrossed on parchment,” the task fell to Matlack, whose script was compact but neat and legible — perfect for the first and most famous of American documents. Now you, too, can write that way…

But this isn’t completely true. The original Declaration of Independence inscribed on vellum, according to the National Archives and Records Administration where it is preserved, already in 1820 began “showing signs of age. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned printer William J. Stone to make a full-size copperplate engraving. This plate was used to print copies of the Declaration. The 1823 Stone engraving is the most frequently reproduced version of the Declaration” — and thus the copy of Matlack’s penmanship on Stone’s engraving is the source of the typeface produced by Three Islands Press.

The characters in casual human handwriting are rarely identical, thus using a script typeface often suffers from lack of authenticity, because each incarnation of each character does not differ from the last. That’s why a good script typeface is rich with alternate glyphs. American Scribe is still not very rich in them and the sequence of identical incarnations of the same letters start to bother already in the second line of the tracklist at the very first encounter.

What is the common purpose of script typefaces? — Wedding cards, for example. Scripts are not for continuous reading. Absolutely not for immersive reading. Any book on typography and type design mentioning scripts says that (and so does the critical thinking). Stop Stealing Sheep by Erik Spiekermann, probably the best book on typography for kindergarden boys and girls, says that clearly: “Most [script typefaces], however, are not suited to long spells of reading, just as sandals are very comfortable, but not when walking on rocky roads.”²⁰ So, can it be that the typographer who chose a script typeface for setting 1245 words never read a single specialized book? — Easy.

In the chapter “Script types” of his The Elements of Typographic Style Robert Bringhurst repeats the same idea, and also confirms another one which I had when I first held Totschläger in my hands — that commissioned calligraphy would serve a much better job for the design of the album. I’ll return to this idea later.

Scripts had an importance in the world of commercial letterpress that they lack in the world of two-dimensional printing. Handwritten originals are expensive to photoengrave for letterpress reproduction. But specially commissioned calligraphy is easy to incorporate into artwork destined for the offset press. The best script to supplement a typographic page is now therefore more likely to be custom made.

In general, scripts are also more closely tied to particular moods, places and times than text types […] scripts remain important in typography for the contrast they provide when a single word or line must be set off from a block of formal text.²¹

(For those who know neither Bringhurst nor Spiekermann I’d say those two books are among the three probably easiest and clearest introductory books to the craft {or art?} of typography, together with Jan Tschichold’s The Form of The Book. Spiekermann is light, Bringhurst is smart, Tschichold is merciless.)

The appearance of a script typeface in the album design, especially the script so clearly related to the history of the official USA and so far from Abigor, seems dubious — nothing says the choice was necessary or unavoidable. Its combination with Fraktur is even more questionable. Normally, a clear-minded typographer would need serious reasons to mix a metal font from the early sixteenth century with a two and a half centuries younger penmanship from a different tradition. Thus the meaning (if there exists any) behind this solution remains hidden. It may be nothing more than just a fancy, a designers’ wild mood swing.

The only possible reason to begin searching for a foreign type to accompany Fraktur is the aforementioned fact that the album title is in the German language, set in a German font, while almost all other texts are in English, and setting English texts with such a prominently German blackletter would create difficulties for the readers. This is a centuries-old, well-known problem that the readers from non-German conventions have difficulties deciphering Fraktur. That was the reason the German Nazis abolished the use of Fraktur when The Third Reich started growing with new, non German-speaking lands — nobody in the new territories could read the official Reich documents set in Fraktur, thus they turned to Antiqua, “polished/slippery and foreign” to the German eye.²²

Black metal history knows at least one manifestation of this problem. A cassette version of Ulver’s Kveldssanger was released under the title Kveldsfanger by the Polish Mystic Production exactly because the guys from the label could not distinguish ſ from f. The first time I heard Kveldssanger was on a tape copied from the CD, and the tape owner wrote on the tape insert with his hand Kveldsfanger as well. Keeping this in mind we understand that if set in Fraktur the subtitle “a saintslayer’s songbook” would look confusing, because the letter k would just appear unrecognizable for most of the audience.

American Scribe typeface itself is far from perfect. To name a few problems:

- Lower-case s is never connected with any following letter, thus creating unnecessary spaces in the writing.

- Left sidebearing of the upper-case D sets each word starting with D two spaces afar. See the title “La Plus Longue Nuit Du Diable” in the tracklist where it is very prominent, or in the line “the noble Duke’s grim countenance.” A living human writing does not create such spaces between the words, even knowing D may take additional space. Compare with a similar case of e D in the US Declaration of Independence:

- More variations of i and its combinations with other letters are missing. And all diacritics needed higher attention.

German speakers used to write with their own script — Kurrentschrift. Why didn’t the designers choose that one? It would’ve added to the references to German national, and wouldn’t have looked as foreign in the album subtitle nor in the lyrics, even though they’re in English. It would just look more right next to the Fraktur.

1901: Linotext

The typeface was designed by Morris Fuller Benton, released by Linotype.

It is the third typeface in the album design, but is exclusive to the CD version in which it appears on the disc itself. Probably it’s not the Linotype version, but one of its clones.

Under no circumstances must characters of the same style of face be mixed with others.²³ Using two different blackletter categories in one design, especially on a single surface, is screwing a bolt in a wrong pitch, striping the thread.

Setting with uppercase exclusively is traditional in Roman but unconventional in blackletter. Metal history does not excuse the error: BATHORY and BURZUM set in uppercase blackletter is an error. Deathspell Omega and Motörhead set in both upper- and lowercase blackletter is correct.

…romans can be used in two ways which have a rather different effect: as capitals alone and as capitals with lowercase letters. Setting in blackletter we cannot use capitals alone as an independent font. If a contrast is required making a word stand out, it may be achieved by using a font of a different size. The fact that we can achieve different effects with one size of romans […] is another one of its great advantages.²⁴

1932: Times New Roman

Released ninety years ago but still preserving its popularity, Times New Roman is one of those few text types which (maybe until very recently) carried no historic associations and fully belonged to our days.

The typeface (or one of its numerous incarnations) is used thrice in the design — each time for the W. T. C. 666 sign exclusively: on the disc label, in the booklet and in the gatefold.

As the words of different characters in a play aren’t normally set in individual type, so there is no need to reward the record label with individual presence in the design. The idea to make it stand out is in our case beyond discussion because the label’s logo is present in the layout and is enough. Although even the label logo is excessive — it would be enough to put it in text “published by World Terror Committee in 2020” or similar, without adding the logo.

Or… there still must be some metaphysical coherence in taking an action and setting the three letters, one number and a dot — 6 C T W . — with an individual typeface. I just don’t get it yet.

Abigor logo

The logo on the cover originates in the demo days. If my observations are correct, it was updated once for the debut album, then once again in the days of Structures of Immortality EP (best seen on Origo Regium compilation cover) when the typeface in it was changed, and since the days of Fractal Possession we see probably the last (current) version of it.

I've been familiar with it since late ’90s when I was too young to question any designs in music. I’ve never questioned the logo ever since, and trying to look at it now afresh and with a critical perspective is not that simple — I’m just too used to it.

Clearly it’s a perfectly recognizable logo, and it seems to not get old — after all Abigor don’t cease to channel black metal in its truest form, and I see those things connected. None of younger bands’ logos come close to its originality; just take a look at the next festival patch-poster you discover. Abigor logo works and indeed it does its job well for such a work as Totschläger, rooted in metal story. (Remark: I see the album as the band’s tribute to themselves, and the Chapter III of the survey, dealing with music and lyrics, will be focused on it.)

But if I try at least a bit to look at the logo from outside of my bubble of Abigor fandom, critically, a few ideas come to mind. Its creation was timely in the demo days and in the ’90s era black metal, when the scene was designed mostly intuitively. Now, for a possible outsider, it may appear as if it was created by a Japanese designer, who did not know in Europe they mostly read and write from left to right. One of the exceptions is the shop signs on which the text can appear written top-to-bottom.

The current update of the logo is set in a weird typeface copying traits of both (aforementioned) Linotext and the late nineteenth or even early twentieth century Engravers Old English. It is the fifth typeface used in the design, and the third different blackletter in it.

Andreas Gamerith’s painting for the album cover is a prominent work. Putting any logo on it provokes questions. Does it deserve it? Is it the logo which is missing in the painting? I don’t think so. The painting is complete and demands no labels on top. In case the band and the label cared about the sales in record-stores where the products are discovered and examined in-hand, they could provide such stores with additional stickers to be put on the plastic envelope which the LP comes with. In case of the online shops they anyhow mark the products with text, and the products are being found by the title and the description, not by the logo on the cover.

Additionally, it won’t harm to understand that in the past twenty years the role of logotypes decreased dramatically. Nowadays neither logos, nor labels, nor colors are a relevant medium for a brand’s recognizability. Those are exactly the typefaces and typography which stick to the readers’ memories and it’s where the focus of any “branding” activity shall be.

Typefaces summary

What matters in good writing is the exact opposite of what was generally preached at least until recently: not the expression of the (mostly modest) personality, but complete self-abandonment, self-denial if you will, in the service of the correctly grasped task.²⁵

- The main chosen typefaces are of low quality, selected without competence and in a hurry.

- Instead of American Scribe the choice could be the lettering which accompanies the engravings of Compositions By John Flaxman.

- Or it could be Kurrent script (Deutsche Kurrentschrift) — the handwriting style sometimes referred to as written counterpart to Fraktur. This would’ve worked at least as good as American Scribe, but probably better. That would’ve been more consistent.

- A typeface with less relation to any particular country’s traditions could be chosen. There are plenty blackletters which aren’t yet prominent in metal designs, and it is possible those which haven’t yet at all been used in black metal.

- Or just use an English blackletter, linking to the band photo “made” in London, to booklet illustrations (which are reworks of those by the Englishman Flaxman), to the jawbone on the front cover (English tradition as we have already charged), and to the primary language of the lyrics.

- Use not the handwriting but a Roman type for all texts in English; Fraktur for everything in German. It’s a traditional approach found in thousands of books since the printing press came to Europe.

- All the writing could be done with the same tool and hand as the illustrations. The logo on the cover, too, could be re-created the same way. (A reworked logo could be a link to old tape-copying and fanzine designs when the editors copied bands’ branding by themselves.) A skilled hand would’ve made it great.

One of these harder and truly laborious ways, and a patient research, would’ve brought greater results, preserving consistency and, if well done, even displaying further maturity. Schrift ist wie alle Kunst nichts für ungeduldige Naturen.²⁶

Generally, Totschläger typography appears like a newsfeed: we follow by interests, the follows have their own, and the feed brings a post on the sixteenth century font, eighteenth century penmanship, Times New Roman, typography of the computer era… and so on.

Continue reading — https://telegra.ph/Abigor-Totschlaeger-design-pt2-03-24