a Twitter thread from @PhDniX

@TwitterVid_bot1.

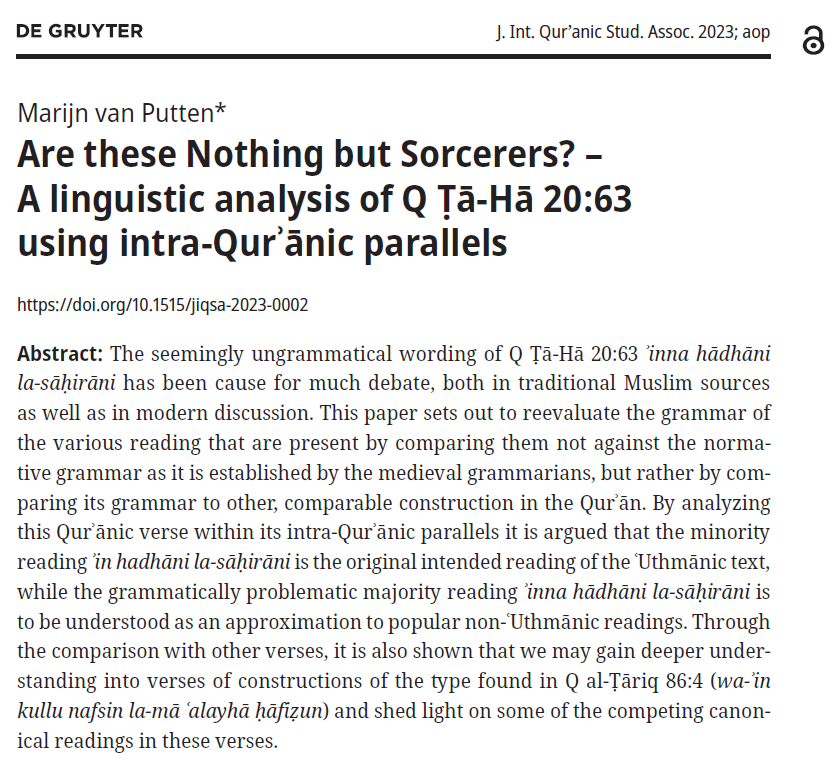

New Article alert! This one is Open Access and you can download and read it yourself!

But let my try to write a short summary of what I tried to do in this article:

In the article I tackle a controversial passage in the verse Q20:63.

https://doi.org/10.1515/jiqsa-2023-0002

2.

Why is it controversial? Well it's long been recognised as a verse that appears to have a grammatical error. The consonantal skeleton ان هذ(ا)ن لسحرن is read by the majority of the readers as ʾinna hāḏāni la-sāḥirāni, which is weird. ʾinna should be followed by hāḏayni.

3.

Dissatisfaction with this consonantal skeleton has a long pedigree. Already in our earliest exegetical sources, e.g. Al-Farrāʾ (d. 207 AH), we find reports that cite Muhammad's wife ʿĀʾišah saying that this is a scribal error in the Uthmanic text.

4.

In the paper I set out to explain the grammar of this form not by explanations that have been given for it based on external evidence, but rather to see whether we can understand the form from Quranic-internal arguments.

5.

The majority reading ʾinna hāḏāni la-sāḥirāni is extremely difficult to explain with quranic-internal arguments. There are no other cases of the dual demonstrative hāḏāni in an accusative context, but there is little reason to assume it shouldn't inflect for case here.

6.

But the minority reading ʾin hāḏān(n)i la-sāḥirāni which is only adhered to by Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim and Ibn Kaṯīr I believe can be understood quranic-internally and therefore also strikes me as most likely the intended reading of the Uthmanic text.

7.

I reject the rather bizarre understanding of ʾin hāḏāni la-sāḥirāni as having the negator ʾin and followed by la- in the meaning of ʾillā "except". In that interpretation the verse would mean "these are nothing but/only sorcerers!", which shows up in some translations.

8.

There simply is not a single parallel in the whole of the Quran where la- has the meaning ʾillā. So such an understanding of this verse cannot be supported by Quranic internal evidence, and even external evidence is basically grammarians saying: "because I say so".

9.

So then I explore another option: ʾinna belongs to a group of particles that have a geminated form that takes the accusative (lākinna "but" and ʾanna "that") but have a shortened form that takes the nominative (lākin/ʾan).

10.

Such shortened have to obligatorily be used when they stand in front of a verb, but even before nouns such forms can occur, and we find a good number of cases where the Quranic readers disagree on lākinna/lākin before nouns.

11.

ʾinna has a clear examples of ʾin that occurs before verbs, and grammarians clearly note that such a form can also occur before nouns. Thus they say:

ʾinna zaydan la-qāʾimun "Zayd is standing" is equivalent to ʾin zaydun la-qāʾimun.

That looks a lot like Ḥafṣ' Q20:63!

12.

But just because Grammarians can create example sentences that look like a problematic verse of course does not mean Q20:63 in that reading is grammatical within the Quranic corpus.

This is an important methodological point of the paper.

13.

Many things the Arab grammarians consider 'good Arabic' are constructions that *never* occur in the Quran, and we are looking at grammarians speaking centuries later. There is no reason to think that what is possible in some form of Arabic would be possible in the Quran's Arabic.

14.

To give an analogy:

- I am not an idiot

- I ain't an idiot

Both are good English sentences. But not every English speaker is going to find both constructions equally acceptable. This depends on your own dialect/idiolect.

The grammarians don't really think in those terms.

15.

So can we find evidence of a Q20:63-like construction elsewhere in the Quran to show that understanding it as a shortened ʾinna ... la- is something that has some backing elsewhere in the Quranic text. And the answer to that, I argue, is yes!

16.

There are a number of phrases in the Quran which start with ʾin + nominative noun (always kull!) followed by la- followed by a relative clause introduced by mā. Translating la-mā as a relative clause is a bit overwrought, but that's what I've done in to highlight the structure.

17.

But Marijn, you might say, that's not how I know these verses! The word after the kull phrase should be lammā, not la-mā!

That's right, that's a difference between some of the canonical readers. la-mā strikes me as easier to defend than lammā.

18.

Interestingly lammā in these constructions is also explained as meaning ʾillā "except" once again understanding these verses once again as a negator ʾin + ʾillā "nothing but X" constructions. Here too, I really don't think that's defensible.

19.

First and foremost because there are no cases where lammā means "except" at all. Some parallels are mentioned where it takes on the meaning of ʾil-lā "if not" in oaths, but this is not such a construction and ʾillā does not mean "if not". Internal evidence doesn't support it.

20.

But there is an even strong counterargument agains tthat understanding the la-mā/lammā occurs in a very similar construct in Q11:111 where the noun following the initial particle is in the accusative and thus it is ʾinna kullan.

21.

This clearly shows that in these constructions the ʾin in ان كل لما is functionnaly equivalent to ʾinna in ان كلا لما. Since ʾinna cannot be a negator and thus Q11:111 cannot be understood as a ʾin ... ʾillā construction, we must not do that for the ان كل لما cases either!

22.

There are a number of medieval grammarians that basically agree with this assessment, and struggle a bit with the lammā form. Al-Farrāʾ tries to suggest lammā is a contraction is la-man-mā "certainly whoever", cute idea but difficult to prove and syntacticalyl a bit odd.

23.

Al-Farrāʾ himself seems to prefer la-mā and quotes his teacher and canonical reader al-Kisāʾī as saying: "I am not aware of an interpretation of lammā with gemination in recitation". If lammā is a valid reading at all, I suggest it's an irregular geminated form of la-mā.

24.

Q11:111 helps bridge the gap. It shows that ʾin X:nom la-Y is syntactically identical to ʾinna X:acc la-Y. ʾinna X:acc la-Y is well-attested throughout the Quran. And thus Q20:63 can best be understood as representing the rare, but quranic-internal attested shortened form.

25.

This means that Q20:63 is grammatical in the minority reading of Ḥafṣ and Ibn Kaṯīr, and the rasm is *not* la scribal error, but intended to represent that reading. It means that this verse means "These are certainly sorcerers!" and not "These are nothing but sorcerers!"

26.

Thus this paper not only tackles Q20:63 but actually also leads to reanalysis of the ʾin kull lam(m)ā constructions, which also frequently get translated as "nothing but" constructions (wrong imho).

The Quran can be used to understand the Quran, and to evaluate competing readings

27.

There is an excursus at the end of the article where I discuss a almost throwaway -- but interesting! -- suggestion of Nicolai Sinai that we should talk the majority reading ʾinna hāḏāni la-sāḥirāni as the more difficult, and thus more probably reading.

28.

As my reading argues for the intendedness of the minority reading, I of course disagree. I think the majority reading was generated through an interesting interaction between a canonical text and pre-canonical variation in this verse. Read the article for details!

Read this thread on Twitter

Made by @TwitterVid_bot