Заявление куратора | Curatorial statement

Первая из серии Биеннале, объединенных общей проблемной рамкой трудного наследия, реализованная в Волгограде в ноябре-декабре 2021 г., была посвящена актуальному осмыслению военного наследия и форматов его презентации, сценариям послевоенного развития территорий, а также разработке прототипов построения мира и проработки травматического опыта методами культурной дипломатии.

Трудным наследием становится не каждый факт сложного прошлого: мы говорим о тех культурных травмах (неважно, насколько хронологически они отделены от нас), которые оказывают влияние на ландшафт настоящего и нашу экономику памяти. Задача проработки культурной травмы заключается не в том, чтобы забыть (преступления против человечности нельзя преодолеть забвением) или заместить её позитивной повесткой, а в том, чтобы найти способы, как справиться с болью памяти, снизить эффект «мнемалгии» и ослабить работу страдания, чтобы найти ресурсы для построения образов совместного будущего. Игнорирование этой необходимости погружает общество в лимб постоянного воспроизведения деструктивных практик и бесконечной ретравматизации.

Современное искусство и выставочные форматы работы оказываются, пожалуй, одними из немногих доступных и легитимных инструментов осмысления темы, позволяющих тонко и чувствительно работать с трудным наследием. С одной стороны, искусство в состоянии конвертировать приватные травматичные воспоминания в факты социальной и культурной памяти: невыразимое страдание должно сначала обрести свое выражение, чтобы обеспечить идентификацию и эмпатию. А с другой — способствовать со-разделению культурной травмы отдельных сообществ с её не-носителями, помогать смене коммеморативной перспективы для преодоления причиняющей боль асимметрии памяти. Асимметрия памяти устраняется не взаимным забвением, а процессами формирования общей — инклюзивной — памяти, говорящей о страданиях обеих сторон, как о ситуации, дающей возможность примирения. Лишь сопереживание и признание чужих страданий могут справиться с фатальным размежеванием. Мы должны синхронизироваться в нашем прошлом, чтобы благополучно со-существовать в настоящем. Нам еще предстоит пройти долгий путь, наполненный разговорами о справедливости, признании и взаимной ответственности, поисками способов «охлаждения» травмы и напряженности, покаяния и прощения для построения совместного — мирного — будущего. Нашим проектом мы хотели лишь начать разговор о важности этих поисков. Биеннале не претендует на разработку готовых решений, а скорее является платформой, в рамках которой эти решения могут быть предложены, апробированы и открыто обсуждены.

В проекте приняли участие художники, кураторы и херитологи, представляющие территории с крайне разнящимся опытом и подходами к осмыслению трудного военного наследия — Южный и Северо-Кавказский федеральные округа. При этом актуальность обращения к реинтерпретации военного наследия на этих территориях поддерживается подключенностью их жителей к проблематике через семейные и личные истории.

На юге России преобладающие форматы репрезентации и интерпретации военного наследия можно признать малоэффективными: доминирующие форматы «патриотического воспитания» в содержании большинства проектов слабо связаны с потребностями проработки культурной травмы, официальный дискурс сосредоточен на героике и отличается патетической стилистикой, что не позволяет достаточно эффективно осуществить мыслительную операцию продуктивной переработки травматического опыта, связанного с военным наследием территории. На Северном Кавказе попыток осмысления, репрезентации и интерпретации военных событий институтами наследия почти не предпринимается из-за отсутствия стратегий и видения этого процесса, а также в силу потенциальной конфликтогенности проблематики в случае недостаточно аккуратного и взвешенного подхода к ее осмыслению.

Выбор места реализации проекта не произволен: при взгляде на культурно-образовательное поле может сложиться впечатление, что Волгоград погружен в посттравматический синдром, не имея возможности моделировать сценарии будущего: один из музеев каждый год реконструирует пленение генерал-фельдмаршала Паулюса, другой (посвященный наследию немцев-переселенцев XVIII века) — разыгрывает на своей территории взятие Рейхстага. Военное наследие нередко становится объектом манипуляций: политических (депутат Государственной Думы снимает на Мамаевом кургане клип, в котором дети поют о своей готовности погибнуть ради завоевания Аляски), индустрии развлечений (одевание детей в военную форму и раздача еды времен войны в торговых центрах превращают войну в косплей), сомнительных форматов «патриотического воспитания» (работники детского сада ставят детей в снег на колени, выкладывая из их тел цифры в память о военных событиях). Героические дискурсы о войне замещают траурные и скорбные, превращая войну не в источник страха, но в повод для гордости. Волгоград, имея в основе своего культурного кода обширное военное наследие, мог бы стать центром его осмысления и гуманизации темы, но все вышеперечисленное — как и все чаще звучащий лозунг «Можем повторить» вместо «Лишь бы не было войны» — превращают войну в повседневность и имплементируют агрессивные установки применительно к реликтам трагического прошлого. Городу остро требуется коммеморативное перепрограммирование и новые мнемо-технологии, способные выстраивать здоровый и конструктивный разговор о трудном прошлом.

На Северном Кавказе память о пережитых военных конфликтах вызывает совершенно другую реакцию, но этот опыт по-прежнему не отрефлексирован институтами наследия. Большинство межэтнических и территориальных конфликтов до сих пор находятся в «замороженном» состоянии. Единственный вариант решения ситуации — это бережный и тонкий поиск прототипов решений на уровне культурной и народной дипломатии вне политического контекста. Отказ от поиска решения рано или поздно может привести к новой эскалации этих конфликтов.

Помимо собственно военных действий, еще одним из непроговоренных и неосмысленных пластов трудного наследия является наследие терактов как продолжения вооруженных конфликтов на Северном Кавказе, вынесенного за пределы эпицентра. Эхо конфликтов недавнего времени вызвало волну исламофобии и кавказофобии, которая до сих пор остро проявляется в форме явной и скрытой дискриминации.

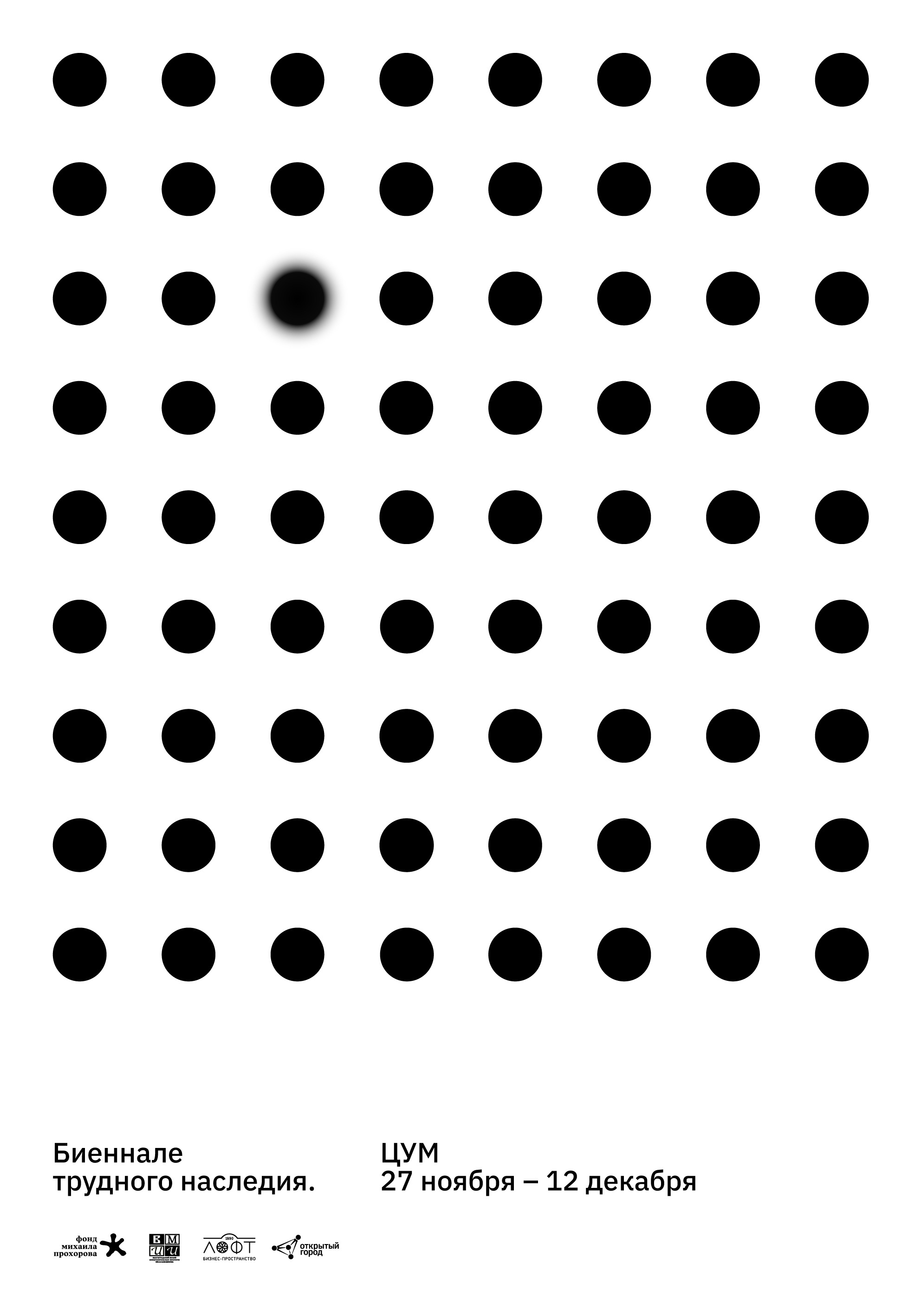

В основу визуального стиля проекта легла идея оптических аберраций, связанных с невозможностью аккомодации взгляда. В качестве визуальной метафоры мы выбрали скотому (от греч. skotos — «темнота») — участок полного или частичного выпадения поля зрения. Трудное наследие — это не всегда очевидная и острая тема, которая вызывает полемику, диссенсус и антагонизм в обществе, призывающие активизировать его проработку и поиск решений, а подчас что-то сокрытое и неявное, исключенное из публичного дискурса, непроговариваемое, избегаемое и игнорируемое для анализа и критической рефлексии, цензурированное или подвергающееся самоцензуре и вытеснению из-за возможной ретравматизации. Факт культурной травмы часто даже не осознается и не диагностируется: картина произошедшего замутнена / неотчетлива / неопределенна / туманна / расплывчата / плохо различима. Все чаще трудное прошлое окутывается молчанием и неразличимостью, чтобы не вывести настоящее из оцепенения. Размытый круг логотипа — это болевая точка и зияние, не позволяющее ухватить цельную картину. Задача биеннале — целенаправленная фокусировка на болевых точках для поиска новых языков и грамматик, на основе которых возможен разговор о трудном прошлом для разработки методов решений. Это во многом и задает инструментальность и технологичность нашего подхода.

Задуманный нами как проект-предостережение, призванный «починить» текущие аберрации памяти, он не смог глобально повлиять на ситуацию. Но мы по-прежнему верим, что культура и искусство — это один из немногих доступных на настоящий момент инструментов изменений. Мы по-прежнему продолжаем верить, что «никто не имеет большего права, чем другой, на существование в данном месте земли».

Выражаем признательность Благотворительному фонду Михаила Прохорова, Волгоградскому музею изобразительных искусств им. И. Машкова, креативному пространству «Лофт1890» за возможность реализации проекта, а также всем художникам и участникам за открытость, готовность к диалогу, атмосферу поддержки и заботы и тот осознанный, интеллектуально насыщенный путь, который все мы прошли вместе.

Идея: Антон Вальковский, Надежда Стародубцева. Куратор проекта: Антон Вальковский. Финансовый координатор: Валерия Патуева. Технический координатор: Стас Азаров. Координаторы: Виктория Демьяновская, Севда Байрактар. Концепция экспозиционного дизайна: Артем Антипин. Визуальный стиль, макет, верстка: Сергей Жигарев. Монтаж и демонтаж экспозиции: Стас Азаров, Тамара Шипицина, Антон Шипицин, Гала Измайлова, Надежда Стародубцева, Антон Вальковский. Операторская работа, монтаж: Евгений Иванов. Фотодокументация: Александр Балуев, Ольга Юнашева, Андрей Захаров, Василий Колотилов. Волонтеры: Анна Бачурина, Алина Болтырова, Татьяна Лысикова, Манижа Розикова, Анастасия Федотова, Анжелика Чикова, Валерия Шишкина, Анастасия Яндринская.

Curatorial statement

The first issue of the Biennial under the common frame of difficult heritage was realized in Volgograd in November-December 2021 and was dedicated to the contemporary comprehension of war heritage and formats of its presentation, scenarios of post-war development of territories, as well as the development of prototypes for peace building and working through traumatic experience by methods of cultural diplomacy.

It is not every fact of our complex past that becomes a difficult heritage: we are talking about those cultural traumas (no matter how far away in time) that affect the landscape of the present and our economy of memory. The goal of working through cultural trauma is not to forget it (crimes against humanity cannot be overcome by forgetting) or to replace it with a positive agenda, but to find ways to deal with the pain of memory, to reduce the effect of “mnemalgia” and to lessen the work of suffering in order to find resources for constructing a vision of a shared future. Ignoring this need plunges society into a limbo of constant reproduction of destructive practices and endless retraumatization.

Contemporary art and exhibition formats turn out to be perhaps one of the few available and legitimate tools for reflecting on the topic, allowing for subtle and sensitive work with difficult heritage. On the one hand, art is able to convert private traumatic memories into facts of social and cultural memory: the unspeakable suffering must first find expression in order to ensure identification and empathy. And on the other hand, it promotes sharing of cultural trauma of individual communities with those who don’t bear it, and helps change the commemorative perspective in order to overcome the painful skewness of memory. This skewness is not resolved by mutual forgetting, but by processes of building a common inclusive memory that speaks to the suffering of both sides in a situation that offers the possibility of reconciliation: only empathy and recognition of others’ suffering can overcome fatal dissociation. We must synchronize in our past in order to coexist safely in the present. We still have a long way ahead of us, filled with conversations about justice, acceptance of guilt and mutual responsibility, finding ways to “cool down” trauma and tension, discovering repentance and forgiveness to build a shared peaceful future. With our project, we seek to start a conversation about the importance of this search. The Biennial does not pretend to develop ready-made solutions, but rather creates a space where these solutions can be proposed, tested, and openly discussed.

The project brought together artists, curators, and heritologists, representing territories with extremely different experiences and approaches to the reflection of difficult war heritage: the Southern and the North Caucasian Federal Districts. At the same time, the relevance of addressing the reinterpretation of war heritage in these territories is supported by the involvement of their inhabitants through family and personal stories.

In the south of Russia, the prevailing formats of representation and interpretation of war heritage can be recognized as ineffective: the dominant formats of “patriotic education” within most projects have little to do with the needs of working through cultural trauma; official discourse is focused on heroics and is characterized by a pathos-packed style, which does not allow for efficient, thoughtful, and productive processing of traumatic experience related to the war heritage of the territory. In the North Caucasus, there are almost no attempts to comprehend, represent, and interpret war events by heritage institutions due to the lack of strategies and visions for this process, as well as due to the fact that the range of issues may potentially provoke a conflict if an approach chosen for the discussion is not diligent and balanced enough.

The choice of the project site is not arbitrary: a single glance at the cultural and educational spheres of life in Volgograd may give the impression that the city is stuck in 200 days of war like in the post-traumatic syndrome, unable to produce scenarios for the future. One of the local museums theatrically recreates the capture of field marshal Friedrich Paulus every year; another one, dedicated to the heritage of German settlers of the 18th century, turns its buildings into the Reichstag and re-enacts its taking. The war heritage often becomes subject to manipulation, be it political (a State Duma deputy films a clip at the Mamayev Kurgan Memorial Complex showing children singing about their willingness to die for the conquest of Alaska), by the entertainment industry (the practice of dressing children in military uniform and giving out war-time food in shopping malls turns the war into cosplay), or for dubious formats of “patriotic education” (kindergarten workers make children kneel in the snow, arranging their bodies into numbers to commemorate the war events). Heroic narratives replace mournful and sorrowful ones, making war not a cause for fear, but something to be proud about. Volgograd, having an extensive war heritage at the core of its cultural code, could have become a center of reflection and humanization of the topic, but the aforementioned factors, as well as the increasingly frequent slogan “We can repeat it” instead of “Never again,” turn the city into an all-Russian center of hostility and militaristic rhetoric, transforming war into everyday life and implementing aggressive attitudes towards relics of the tragic past. The city desperately needs commemorative reprogramming and new mnemonic technologies capable of building a healthy and productive conversation about the difficult heritage.

For the North Caucasus, the memory of military conflicts evokes a very different response, but this experience remains unconsidered by heritage institutions. Most interethnic and territorial conflicts are still in a frozen state. The only option for solving the issue is a careful and subtle search for prototypes of solutions at the level of cultural and popular diplomacy outside the political context. Failure to find a solution may sooner or later lead to a new escalation of these conflicts.

In addition to military action itself, another unspoken and unexplored layer of difficult heritage is the legacy of terrorist attacks as an extension of the armed conflicts in the North Caucasus, which have expanded beyond their epicenter. Echoes of the recent conflicts have triggered a wave of Islamophobia and hostility towards the various peoples of the Caucasus, which is still acute in the form of overt and covert discrimination.

The visual style of the project was based on the idea of optical aberrations associated with hindered ocular accommodation. We chose scotoma as a visual metaphor (from Ancient Greek skótos, “darkness”): an area of partial alteration or a blind spot in the field of vision. Difficult heritage is not always an obvious and acute topic that causes heated discussions, dissensus, and antagonism in society, calling to intensify its exploration and search for solutions. Sometimes it is hidden and implicit, excluded from public discourse, unspoken, avoided, and ignored for analysis and critical reflection, censored or self-censored, and ousted because of the potential retraumatization. The fact of cultural trauma is often not even conscious and diagnosable: the picture of what happened is obscured / unclear / hazy / vague / blurred / poorly discernible. More often than not, the difficult past is shrouded in silence and insensibility so as not to bring the present out of its trance. The blurred circle of the logo is a pressure point and a chasm that does not allow one to grasp the whole picture. The goal of the Biennial is to focus on the painful points in order to find new languages and grammars to talk about the difficult past and develop methods of reaching solutions. This determines the instrumentality and technological effectiveness of our approach in many ways.

The venue for the exhibition part of the project is the vacant Central Department Store in the Volgograd city center. Half destroyed during the war and completed in the Soviet period, the building contains the traces of war trauma, and is an important metaphor for post-war reconstruction. The basement is still home to the Memory war museum, and in 2022, renovation and restoration work will begin on the above-ground floors to coincide with the relocation of the Mashkov Volgograd Museum of Fine Arts, which is developing themes of urban restoration in its projects. During the Biennial, the Central Department Store appeared before the audience in a completely unique state: abandoned, empty, and deprived of its functional purpose, like a Leviathan's skeleton beached in the middle of the city. We purposely left drill holes in the exhibition space exposed, allowing the audience to see the building’s several chronological layers; and stone and concrete chippings that were left on the floor after technical and construction expertise added connotations of ruin to the premises. Realizing that part of the audience would come to the event because of nostalgic sentiments, it was important for us to separate the exhibition from the architectural environment: we left numerous signs that reference retail outlets in the infrastructural areas, and placed “clues” as triggers for memories. For example, Milana Khalilova’s work reminds us of the textile department on the third floor, and Anna Vasilevskaya’s installation that represents a ship was mounted in the former toy and shipbuilding models department. During the mediated tours, the curator greeted the audience wearing a badge that was part of the uniform of the department store clerks, which was found in the attic. The windows, freed from the sales stands for the first time in a long while, allowed us to frame the interaction of the exhibition with the cityscape in the background. Following the ecology of the site’s memory, we also used found building materials and remnants of retail equipment as elements of the exhibition design.

This text had undergone significant changes at the time of publication of the catalog, losing much of what we wanted to say at the end of last year. Conceived as a cautionary project designed to mend the current aberrations of memory, it has failed to make a global impact. But we still believe that culture and the arts are two of the few tools of change available at the moment. We continue to believe that “no one has more right than another to a particular part of the earth.”

We express our gratitude to Mikhail Prokhorov Charitable Foundation, Mashkov Volgograd Museum of Fine Arts, and the Loft1890 creative space for making the project possible, as well as to all the artists and participants for being open and ready for dialogue, for creating the atmosphere of support and care, and for coming along with us on this deliberate, intellectually rich journey.

Idea: Anton Valkovsky, Nadezhda Starodubtseva Project curator: Anton Valkovsky Financial coordinator: Valeria Patueva Technical coordinator: Stas Azarov Coordinators: Victoria Demyanovskaya, Sevda Bayraktar Exhibition design concept: Artem Antipin Visual style, catalog make-up and layout: Sergey Zhigarev Installation and dismantling: Stas Azarov, Tamara Shipitsina, Anton Shipitsin, Gala Izmaylova, Nadezhda Starodubtseva, Anton Valkovsky Translator: Elena Son Camera, editing: Evgeny Ivanov Photo credits: Alexander Baluev, Olga Yunasheva, Andrey Zakharov, Vasily Kolotilov Volunteers: Anna Bachurina, Alina Boltyrova, Tatyana Lysikova, Manizha Rozikova, Anastasia Fedotova, Angelika Chikova, Valeria Shishkina, Anastasia Yandrinskaya