Whipping Punishment In Early England

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Crime and Punishment in early 19th century England

**Note: In the United Kingdom, the Regency is a sub-period of the Georgian era (1714-1830) and runs from 1811 to 1820. It is named after the Prince of Wales who, as Prince Regent, took over rule from his ill father, George III, during this time. For the purpose of this article, we consider the Regency era to be from 1800 to 1830, and look at a few things about the time’s justice system.

If you are anything like me- and I sincerely hope you are ’cause that’s gonna make me feel a little less like a weirdo- you do enjoy a cup of coffee along with a suspenseful crime story.

Let’s just admit it- most people thrive on suspenseful stories. Personally, I’ve always had a fascination with crime stories. As morbid as that sounds, my guess is so have you, and so does the rest of the population because the proof is in the pudding. The old newsroom saying “if it bleeds, it leads” is still a mantra and ratings show that if the story is about a fire, accident, or murder –especially murder- the story is usually the most popular one.

I think my reason for feeling drawn to these stories is the same reason for most: we simply cannot wrap our minds around these crimes. We try to think like the criminal, we try to rationalize why a human being would act in such an unfathomable way against another human. But the truth is, no matter how much we research and study these individuals, we will never get a true insight to the inner workings of their usually warped psyche.

We get bits and pieces; we attribute terrible actions to childhood trauma, to untreated mental illness, and sometimes, even bad timing. But we can never truly pinpoint the exact reason why a human snapped. And that fact alone simply boggles our minds.

Trust me when I say that I can go on and on and on and on-well, you get the picture- about this subject, but for now let us get down to the matter at hand: Regency Era crime and punishment.

Crime rates during the Regency Era were relatively low. One might find that strange considering the hardships people of no noble birth had to live through, but the truth is, the people of the early 19th century England lead considerably calm lives, especially when compared to previous times.

When crimes were indeed committed, there were three types of courts:

Magistrate Courts (or justices of the peace) involved people from the local community who were not required to hold any legal qualifications and were responsible for both administering and maintaining the law at county level until 1888, when their administrative power was drastically undermined and taken away.

The principal courts of the Magistrates were Quarter Sessions, which were held four times a year before a bench of magistrates and a jury.

Petty Sessions were introduced later in the 18th century when it became apparent that the four-times-a-year operating system of the Quarter Sessions Court was not enough. Each court had jurisdiction over a specific local authority area and was held before at least two magistrates. They mostly dealt with minor offenses and the recording of new laws.

Assize Courts survived up to the mid 20th century and tried the most serious crimes, including capital offenses. Before 1842, the lines between Quarter Sessions and Assize Courts were rather blurred, with the former often referring serious or difficult cases to the Assize Courts.

The third type of Court in early 19th century England was the King’s Bench. It was the King’s personal court and its main responsibility was to protect the interests of the Crown. There are documented cases that were referred to the King’s Bench, but that only happened when impartial local ruling of the case was considered impossible or compromised.

The system described above was drastically altered in the mid 20th century.

In the early 19th century, the way courts operated was vastly different from today. Court conditions and the treatment of both the victim and the accused were very different, sometimes strange compared to what we now know as the judicial system.

Trials in courts were often very quick, closing in record time cases that would have taken moths to resolve in modern days (bureaucracy, yay!). And while jurors, judges and prosecutors have always been associated with social status, they held remarkably more power back then.

The prosecutor was normally the victim of the crime and the defendant was responsible for explaining away the evidence in their favor while at the same time undermining the prosecutor’s credibility.

And now, I want you to picture a trial where the defendant is accused of stealing the prosecutor’s hen. And trying to convince a jury about the psychological trauma the hen went through.

Oh come on, that’s funny!

If you didn’t laugh, you have no soul…

Hanging was a common punishment and at the same time the most severe, reserved for serious offenses and could only be ordered by the Assizes Court. That is not to say that this punishment was always justly carried out. There are many recorded cases of pick-pocketing and stealing food that were punished with death. Considering poverty rates were very high back then, these types of crimes were usually committed by everyday people in desperate situations. Towards the end of the 1700s, the execution of people for such petty crimes was causing public unrest (duh!).

This growing aversion towards capital punishment became more apparent later on, during the early 19th century, when the death of the prisoner was often recorded but never carried out, and the sentence changed to transportation or imprisonment. This practice lead to the decrease of the number of criminals sentenced to be hanged as the century went on.

I don’t know about you people, between a fashionable choker and the hangman’s rope, I’d rather wear the choker.

Gaols in Regency England were harsh environments that developed systems of mass incarcerations, more often than not including hard labor, rooms of solitary confinement, silence and inadequate medical services.

Ah, heaven on Earth….(hello there, my name is ‘Sarcasm’, nice to meet you!)

While the initial idea was to use these prisons as less strict alternatives to execution and other forms of corporal punishment, gaols soon turned into harsh, terrifying places with two distinct missions: to deter people from committing crimes, but also to rehabilitate the inmates and lead them to moral reform.

A range of other punishments were, however, also frequently imposed.

In order to avoid the gallows, many felons were transported to the American colonies and later in the century, to those in Australia, where they served out their sentences in hard labor. Any criminal with a sentence of 7 years or longer could be transported, sometimes for life.

Though if you ask me, being sent to Australia was enough of a punishment on its own. Have you seen the spiders there?!

Other criminals convicted of lesser crimes were fined, though this was not commonly used as punishment. Most people were too poor and unable to pay.

Oh, the irony of punishing a poor farmer for pick-pocketing…by asking him to pay more money!

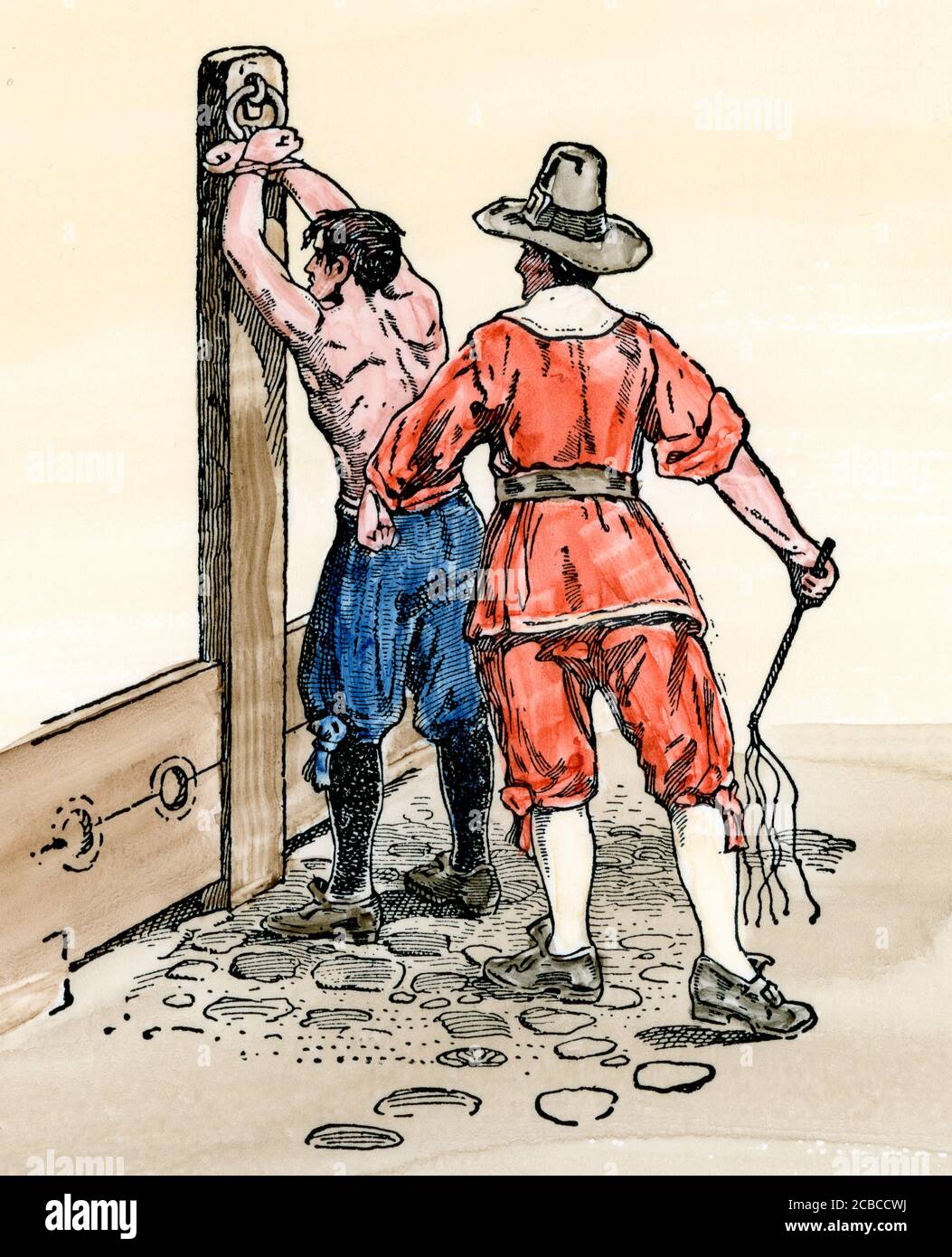

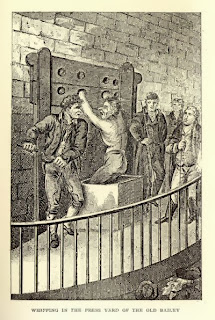

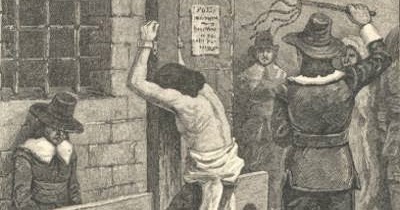

The most common physical punishments were usually accompanied by the element of public shaming, mostly in the form of being whipped ‘at the cart’s tail’, for example or being set in the pillory and pelted with rotten eggs and vegetables. Also, there are documented cases of people being branded on the hand by hot iron (Ouch!).

Over the course of the 18th century and by the time the 19th century rolled around, these practices had been mostly abolished, though whipping still somewhat persisted.

The number of public whippings drastically decreased, but the same cannot be said for private whippings. In fact, the practice increased behind closed doors, often taking the form of disciplinary action by correctional facility officials, youth prison staff, gaol staff members, and even orphanages.

The public of women was abolished in 1817 and men in the 1830s. However, records show that private whippings were not discontinued until 1848.

I don’t know about you, but I sure as hell feel sorry for early 19th century criminals. I mean, alrighty, he stole a noble’s brandy money, but being sent to Australia?

Join Cobalt Fairy's vibrant community of voracious readers on Facebook

© Copyright 2021. All rights reserved.

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings.

Home

>Journals

>Journal of British Studies

>Volume 60 Issue 3

>Law, Status, and the Lash: Judicial Whipping in Early...

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 April 2021

This article focuses on the contested development of judicial whipping as a marker and maker of status in the particular social, cultural, and political context of England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In these years people disputed with special vigor who could be whipped and why, often in battles fought in and around parliaments and the Court of Star Chamber, and often invoking fears of “servility.” Tracing the rise and spread of judicial whipping, its linking with the poor, and disputes over its use, this article demonstrates how whipping served as a distinctively and explicitly status-based disciplinary tool, embedding hierarchical values in the law not just in practice but also in prescript. Some authorities thought the whip appropriate only for the “servile” and, indeed, both valuable and dangerous for its ability to inculcate a “slavish disposition.” After men of the gentry successfully asserted their freedom from the lash, so too did a somewhat expanded group of “free” and “sufficient” men. By the later seventeenth century, challenges over the uses of judicial whipping left it limited ever more firmly to people of low status, affixed by law to offenses typically associated with the insubordinate poor.

Copyright

Copyright © The Author(s), published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the North American Conference on British Studies

Institutional login

Log in with Open Athens, Shibboleth, or your institutional credentials

Personal login

Log in with your Cambridge Core account or society details.

1 Stone, Lawrence, The Crisis of the Aristocracy, 1558–1641 (Oxford, 1965), 34Google Scholar.

2 On distinctively English definitions of aristocratic status, see Bush, M. L., The English Aristocracy: A Comparative Synthesis (Manchester, 1984)Google Scholar. On the amorphous category of “gentlemen” and its expansion in these years, see also Heal, Felicity and Holmes, Clive, The Gentry in England and Wales, 1500–1700 (Stanford, 1994)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

3 The phrases “servile disposition” and “slavish disposition” occur in a variety of early modern texts, but for uses specific to whipping's ability to change the self beyond those cited below, see, for example, Traninger, Anita, “Whipping Boys: Erasmus’ Rhetoric of Corporeal Punishment and Its Discontents,” in The Sense of Suffering: Constructions of Physical Pain in Early Modern Culture, ed. Frans van Dijkhiizen, Jan and Enenkel, Karl A. E. (Leiden, 2009), 39–57, at 49Google Scholar. For a discussion of the varieties of unfreedom and the often classical connotations of references to slavery in the period in which the Atlantic system of racialized chattel slavery was just starting to develop, see Guasco, Michael, Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Philadelphia, 2014)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

4 For particularly useful discussions of “the rule of law” that are attentive to the history of the concept, see Bingham, Tom, The Rule of Law (London, 2010)Google Scholar; and Tamanaha, Brian Z., On the Rule of Law: History, Politics, Theory (Cambridge, 2004)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

5 The classic exchange on the rule of law in sixteenth-century England focused on the degree to which Tudor monarchs acted within the constraints of the law and whether the rule of law did or did not preclude despotism or indicate “consent.” See, in particular, Hurstfield, Joel, “Was There a Tudor Despotism after All?,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th series, no. 17 (1967): 83–108CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Elton, G. R., “The Rule of Law in Sixteenth-Century England,” in Studies in Tudor and Stuart Politics and Government (Cambridge, 1972), 260–84Google Scholar. For a more recent and expanded treatment of the subject, see Baker, John H., “Human Rights and the Rule of Law in Renaissance England,” Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights 2, no. 1 (2004): article 3Google Scholar, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol2/iss1/3. None of these works explicitly stated that the early modern “rule of law” incorporated a claim to equal treatment, but slippage sometimes occurs; see, for example, Hart, James S. Jr., The Rule of Law, 1603–1660: Crown, Courts and Judges (Harlow, 2003), 1Google Scholar, which asserts an expansively defined rule of law. See also the important book by the late Christopher Brooks, W., Law, Politics and Society in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2008), 431Google Scholar, which argues that early modern law did not systematically express hierarchical values. Brooks imported into the prerevolutionary period E. P. Thompson's characterization of a post-1688 “rule of law,” in which claims to equal treatment before the law did figure into the self-justifying rhetoric of authorities.

6 Beier, A. L., Masterless Men: The Vagrancy Problem in England, 1560–1640 (London, 1985), 158–59Google Scholar; Griffiths, Paul, “Introduction: Punishing the English,” in Penal Practice and Culture, 1500–1900: Punishing the English, ed. Devereaux, Simon and Griffiths, Paul (Basingstoke, 2004), 1–35Google Scholar; Paul Griffiths, “Bodies and Souls in Norwich: Punishing Petty Crime, 1540–1700,” in Devereaux and Griffiths, Penal Practice and Culture, 85–120; Martin Ingram, “Shame and Pain: Themes and Variations in Tudor Punishments,” in Devereaux and Griffiths, Penal Practice and Culture, 36–62; Ingram, Martin, Carnal Knowledge: Regulating Sex in England, 1470–1600 (Cambridge, 2017), e.g., 378CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Geltner, Guy, Flogging Others: Corporal Punishment and Cultural Identity from Antiquity to the Present (Amsterdam, 2014)CrossRefGoogle Scholar also describes judicial whipping as primarily an early modern rather than medieval phenomenon. See also Postles, Dave, “Penance and the Market Place: A Reformation Dialogue with the Medieval Church (c. 1250–c.1600),” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 54, no. 3 (2003): 441–68CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Minson, Stuart, “Public Punishment and Urban Space in Early Tudor London,” London Topographical Record, no. 30 (2010): 1–16Google Scholar. On the overlapping and mutually reinforcing links between the violence used in household discipline and the maintenance of public order, see Susan Amussen's classic essay, “Punishment, Discipline, and Power: The Social Meanings of Violence in Early Modern England,” Journal of British Studies 34, no. 1 (1995): 1–34. On the potential links between the turn to whipping, wounding, and so on in early modern punishment and its performance on the stage, see Covington, Sarah, “Cutting, Branding, Whipping, Burning: The Performance of Judicial Wounding in Early Modern England,” in Staging Pain, 1580–1800: Violence and Trauma in British Theatre, ed. Allard, James Robert and Martin, Matthew R. (Farnham, 2009), 93–110Google Scholar.

7 This history is touched on in Mills, Robert, Suspended Animation: Pain, Pleasure and Punishment in Medieval Culture (London, 2005)Google Scholar. For biblical references to whipping, see, for example, Deuteronomy 25:2–3; 2 Samuel 7:14; Proverbs 19:29.

8 Cohen, Esther, “The Animated Pain of the Body,” American Historical Review 105, no. 1 (2000): 36–68CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

9 See Kesselring, K. J., Mercy and Authority in the Tudor State (Cambridge, 2003)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

10 Pym, John, The Speech or Declaration of John Pym (London, 1641), 7Google Scholar. John Lilburne would borrow this passage in his later The Legal Fundamentall Liberties of the People of England (London, 1649), 40.

11 On the ways in which gesture and comportment were thought both to construct and communicate facts about self and identity, see, for example, John Walter, “Gesturing at Authority: Deciphering the Gestural Code of Early Modern England,” The Politics of Gesture: Historical Perspectives, Past and Present, no. 203, issue supplement 4 (2009): 96–127, 125; and Michael Braddick, “Introduction: The Politics of Gesture,” The Politics of Gesture: Historical Perspectives, Past and Present, no. 203, issue supplement 4 (2009): 9–35.

12 On the reordering of early modern society, see, for example, Alexandra Shepard, Accounting for Oneself: Worth, Status, and the Social Order in Early Modern England (Oxford, 2015); Keith Wrightson, “‘Sorts of People’ in Tudor and Stuart England,” in The Middling Sort of People: Culture, Society and Politics in England, 1550–1800, ed. Jonathan Barry and Christopher Brooks (Basingstoke, 1994), 28–51.

13 On the later uses of penal whipping, see Morgan, Gwenda and Rushton, Peter, Rogues, Thieves, and the Rule of Law: The Problem of Law Enforcement in North-East England, 1718–1800 (London, 1998), 73, 132–38Google Scholar; Beattie, J. M., Policing and Punishment in London, 1660–1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror (Oxford, 2001), 286–87, 304–08, 446Google Scholar. See also King, Peter, Crime, Justice and Discretion in England, 1740–1820 (Oxford, 2000), 263, 267, 272–73Google Scholar; Sharpe, J. A., Judicial Punishment in England (London, 1990), 23–24, 76–77Google Scholar; Greg Smith, “‘Civilized People Don't Want to See That Sort of Thing’: The Decline of Physical Punishment in London, 1760–1840,” in Qualities of Mercy: Justice, Punishment, and Discretion, ed. Carolyn Strange (Vancouver, 1996), 21–51; Robert Shoemaker, “Streets of Shame? The Crowd and Public Punishments in London, 1700–1820,” in Devereaux and Griffiths, Penal Practice and Culture, 232–57; Hitchcock, Tim and Shoemaker, Robert, London Lives: Poverty, Crime and the Making of a Modern City, 1690–1800 (Cambridge, 2015), 246–67, 363–64CrossRefGoogle Scholar. For discussions leading to the final end of corporal punishment in the court system, see the precipitating “Cadogan Report”: Committee on Corporal Punishment, The Report of the Departmental Committee on Corporal Punishment, 1938, Cmd. 5684.

For the links made in later years between sexual elements of whipping and corrective lashing in the home, public schools, courts, prisons, and the military, see Gibson, Ian, The English Vice: Beating, Sex and Sha

Girl Yo Teen

Seks Xx Massage Video

Mom Best Xxx Hd Com 2021

Private Stories 18 Wet Wet Wet

Younger Watching Online

JUDICIAL AND PRISON FLOGGING AND WHIPPING IN BRITAIN

Crime and Justice - Punishment Sentences at the Old Bailey ...

Crime and Punishment in early 19th century England ...

Crime and punishment in Elizabethan England - The British ...

A HISTORY OF PUNISHMENTS - Local Histories

Flagellation - Wikipedia

A HISTORY OF PUNISHMENTS - Local Histories

Flogging | punishment | Britannica

Crimes and Punishments in Early-Modern England

Whipping Punishment In Early England

.jpg/220px-Women%27s_prison_punishment_(early_modern_era).jpg)