When Was The London Tube Opened

👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

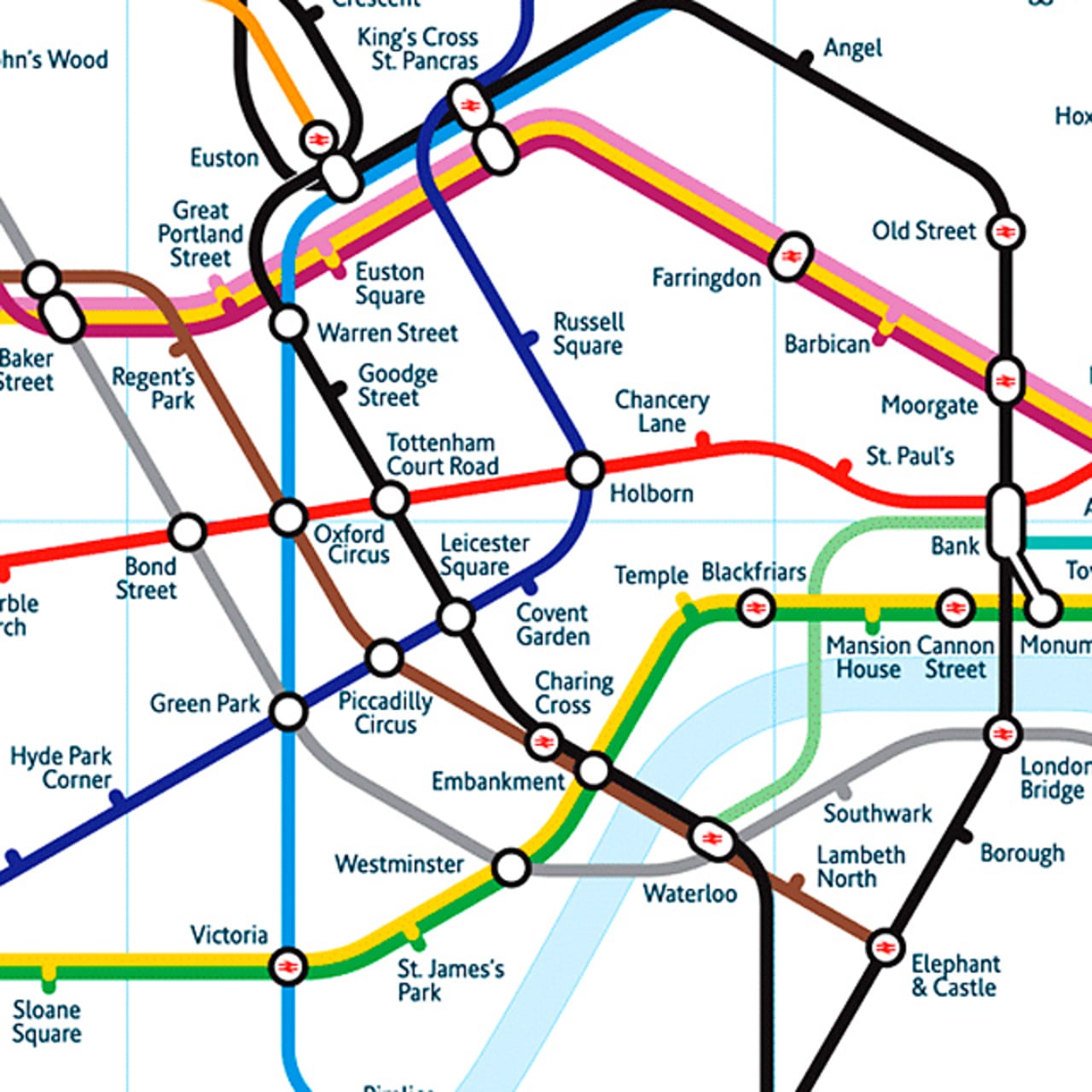

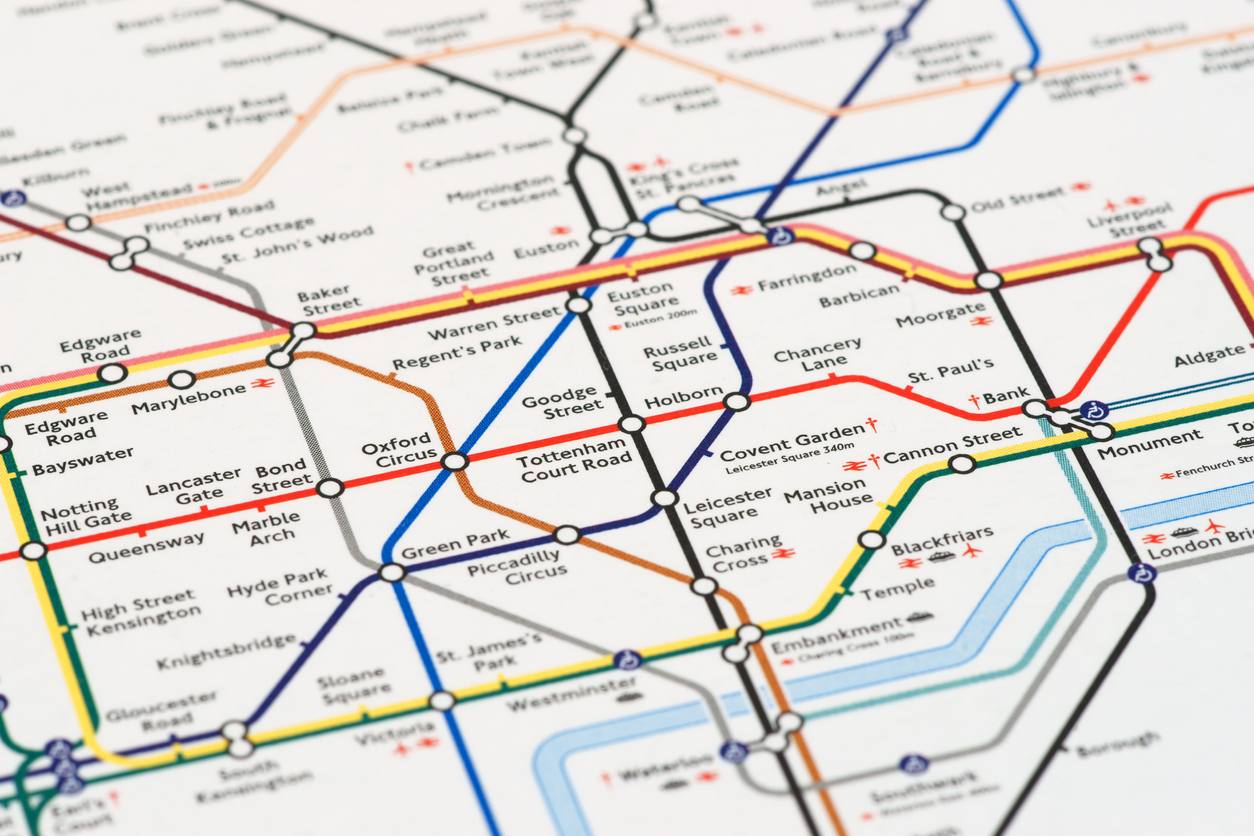

The history of the London Underground began in the 19th century with the construction of the Metropolitan Railway, the world's first underground railway. The Metropolitan Railway, which opened in 1863 using gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives, worked with the District Railway to complete London's Circle line in 1884. Both railways expanded, the Metropolitan eventually extending as far as Verney Junction in Buckinghamshire, more than 50 miles (80 km) from Baker Street and the centre of London. The first deep-level tube line, the City and South London Railway, opened in 1890 with electric trains. This was followed by the Waterloo & City Railway in 1898, the Central London Railway in 1900, and the Great Northern and City Railway in 1904. The Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) was established in 1902 to fund the electrification of the District Railway and to complete and operate three tube lines, the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway, the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway and the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway, which opened in 1906–07. By 1907 the District and Metropolitan Railways had electrified the underground sections of their lines.

Under a joint marketing agreement between most of the companies in the early years of the 20th century, UNDERGROUND signs appeared outside stations in central London. World War I delayed extensions of the Bakerloo and Central London Railways, and people used the tube stations as shelters during Zeppelin air raids by June 1915. After the war, government-backed financial guarantees were used to expand the network, and the tunnels of the City and South London and Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railways were linked at Euston and Kennington, although the combined service was not named the Northern line until later. The Piccadilly line was extended north to Cockfosters and took over District line branches to Harrow (later Uxbridge) and Hounslow. In 1933, the underground railways and all London area tram and bus operators were merged into the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB). The outlying branches of the Metropolitan were closed; various upgrades were planned. The Bakerloo line's extension to take over the Metropolitan's Stanmore branch, and extensions of the Central and Northern lines, formed part of the 1930s New Works Programme. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 halted or interrupted some of this work, and many tube stations were used as air-raid shelters.

The LPTB was nationalised in 1948, and the reconstruction of the mainline railways was given priority over the maintenance of the Underground. In 1953 an unpainted aluminium train entered service on the District line, and this became the standard for new trains. In the early 1960s the Metropolitan line was electrified as far as Amersham, and steam locomotives no longer hauled passenger trains. The Victoria line, a new tube line across central London, opened in 1968–71 with trains driven automatically. In 1976 the isolated Northern City Line was taken over by British Rail and linked up with the mainline railway at Finsbury Park. In 1979 another new route, the Jubilee line, took over part of the Bakerloo line; it was extended through the Docklands to Stratford in 1999.

Under the control of the Greater London Council, London Transport introduced in 1981 a system of fare zones for buses and underground trains that cut the average fare. Fares increased following a legal challenge but the fare zones were retained, and in the mid-1980s the Travelcard and the Capitalcard were introduced. In the early years of the 21st century, London Underground was reorganised in a public–private partnership where private companies upgraded and maintained the infrastructure. In 2003 control passed to Transport for London (TfL), which had been opposed to the arrangement and, following financial failure of the infrastructure companies, had taken full responsibility by 2010. The contactless Oyster card first went on sale in 2003. The East London line closed in 2007 to be converted into a London Overground line, and in December 2009 the Circle line changed from serving a closed loop around the centre of London to a spiral also serving Hammersmith. Currently there is an upgrade programme to increase capacity on several Underground lines, and work is under way on a Northern line extension to Battersea.[1]

In the first half of the 19th century, London had grown greatly and the development of a commuting population arriving by train each day led to traffic congestion with carts, cabs and omnibuses filling the roads.[3] By 1850 there were seven railway termini located around the urban centre of London[4] and the concept of an underground railway linking the City of London with these stations was first proposed in the 1830s. Charles Pearson, Solicitor to the City of London, was a leading promoter of several schemes,[5] and he contributed to the creation of the City Terminus Company to build such a railway from Farringdon to King's Cross in 1852. Although the plan was supported by the City of London, the railway companies were not interested and the company struggled to proceed.[6] In 1854 the Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met) was granted permission to build an underground line at an estimated cost of £1 million. [7] [8] With the Crimean War under way, the Met found it hard to raise the capital,[6] and construction did not start until March 1860.[9] The railway was mostly built using the "cut-and-cover" method from Paddington to King's Cross; east of King's Cross it was built by tunnelling and then followed the culverted River Fleet in an open cutting to the new meat market at Smithfield.[10][11] The 3.75-mile (6 km) railway opened to the public on 10 January 1863, using steam locomotives hauling wooden carriages.[12] It was hailed as a success, carrying 38,000 passengers on the opening day, borrowing trains from other railways to supplement the service.[13] In the first twelve months 9.5 million passengers were carried[11] and in the second twelve months this increased to 12 million.[14]

The Met's early success prompted a flurry of applications to parliament in 1863 for new railways in London, many competing for similar routes. The House of Lords established a select committee that recommended an "inner circuit of railway that should abut, if not actually join, nearly all of the principal railway termini in the Metropolis". Proposals to extend the Met were accepted, and the committee agreed a proposal that a new company, the Metropolitan District Railway (commonly known as the District Railway), be formed to complete the circuit.[15][16] Initially, the District and the Met were closely associated and it was intended that they would merge. The Met's chairman and three other directors were on the board of the District, John Fowler was the engineer of both companies. The construction works for the extensions were let as a single contract[17][18] and the Met initially operated all the services.[19] Struggling under the burden of high construction costs, the District's level of debt meant that merger was no longer attractive to the Met and its directors resigned from the District's board. To improve its finances, the District terminated the operating agreement and began operating its own trains.[20][21] Conflict between the Met and the District and the expense of construction delayed further progress on the completion of the inner circle.[22] In 1879, the Met now wishing to access the South Eastern Railway via the East London Railway (ELR), an Act of Parliament was obtained to complete the circle and link to the ELR.[23] After an official opening ceremony on 17 September and trial running, a complete Circle line service started on 6 October 1884.[24]

The Metropolitan Railway had been extended soon after opening, reaching Hammersmith with the Great Western Railway in 1864 and Richmond over the tracks of the London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) in 1877.[25] The Metropolitan & St John's Wood Railway opened as a single track branch from Baker Street to Swiss Cottage, and this was to become the Met's most important route as it expanded north into the Middlesex countryside, where it stimulated the development of new suburbs. Harrow was reached in 1880, and the line eventually extended as far as Verney Junction in Buckinghamshire, more than 50 miles (80 kilometres) from Baker Street and the centre of London. From the end of the 19th century, the railway shared tracks with the Great Central Railway route out of Marylebone.[26]

By 1871, when the District began operating its own trains, the railway had extended to West Brompton and a terminus at Mansion House.[27] Hammersmith was reached from Earl's Court and services reached Richmond, Ealing, Hounslow and Wimbledon. As part of the project that completed the Circle line in October 1884, the District began to serve Whitechapel.[28] As a result of the expansion, by 1898, 550 trains operated daily.[29] Services began running to Upminster in 1902, after a link to the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway had been built.[30]

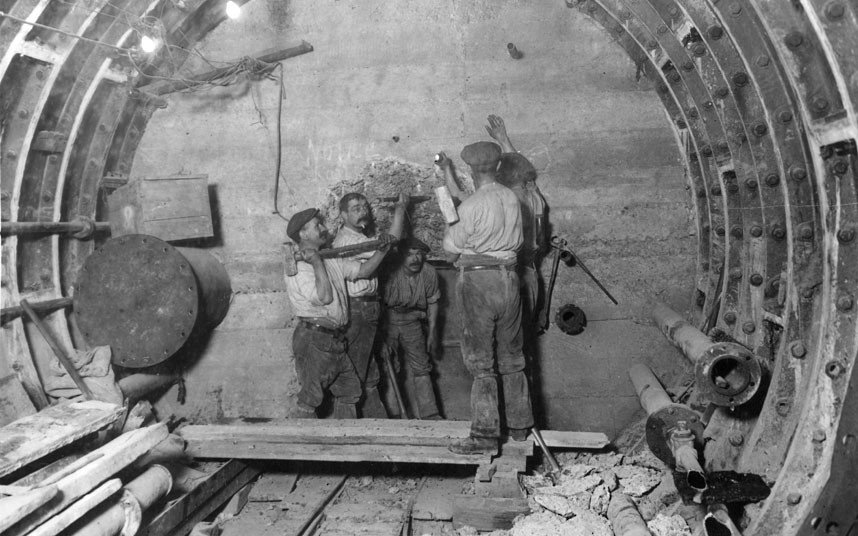

In 1869, a passage was dug through the London Clay under the Thames from Great Tower Hill to Pickle Herring Stairs near Vine Street (now Vine Lane). A circular 7-foot-diameter (2.1 m) tunnel was dug 1,340 feet (410 m), using a wrought iron shield, a method that had been patented in 1864 by Peter William Barlow. A railway was laid in the tunnel and from August 1870 a wooden carriage conveyed passengers from one side to the other. This was uneconomic and the company went bankrupt by the end of the year and the tunnel was converted to pedestrian use, becoming known as the Tower Subway.[31][32] Construction of the City and South London Railway (C&SLR) was started in 1886 by James Henry Greathead using a development of Barlow's shield. Two 10-foot-2-inch (3.10 m) circular tunnels were dug between King William Street (close to today's Monument station) and Elephant and Castle. From Elephant and Castle, the tunnels were a slightly larger 10 feet 6 inches (3.20 m) to Stockwell.[33] This was a legacy of the original intention to haul the trains by cable. The tunnels were bored under the roads to avoid the need for agreement with owners of property on the surface. The original intention to cable-haul the trains changed to electric power when the cable company went bankrupt. A conductor rail energised with +500 volts DC conductor rail for the northbound tunnel and −500 volts for the southbound laid between the running rails, though offset from the centreline, powered the electric locomotives that hauled the carriages. The carriages were fitted with small windows and consequently were nicknamed padded cells.[34][35][36] By 1907, the C&SLR had extended from both ends, south to Clapham Common and north to Euston.[37]

In 1898, the Waterloo & City Railway was opened between London & South Western Railway's terminus at Waterloo station and a station in the City. Operated by the L&SWR, the short electrified line used four-car electric multiple units.[38] Two 11 feet 8+1⁄4 inches (3.562 m) diameter tunnels were dug beneath the roads between Shepherd's Bush and Bank for the Central London Railway (CLR). In 1900 this opened, charging a flat fare of 2d (approximately 91p today),[39] becoming known as the "Twopenny tube" and by the end of the year carrying nearly 15 million passengers. Initially electric locomotives hauled carriages, but the heavy locomotives caused vibrations that could be felt on the surface. In 1902–03 the carriages were reformed into multiple units using a control system developed by Frank Sprague in Chicago. The CLR was extended to Wood Lane (near White City) in 1908 and Liverpool Street in 1912.[40] The Great Northern & City Railway was built to take main line trains from the Great Northern Railway (GNR) at Finsbury Park to the City at a terminus at Moorgate. However the GNR refused permission for trains to use its Finsbury Park station, so platforms were built beneath the station instead and public service on the line, using electric multiple units, began in 1904.[41]

On the District and Metropolitan Railways, the use of steam locomotives led to smoke-filled stations and carriages that were unpopular with passengers and electrification was seen as the way forward.[42] Electric traction was still in its infancy and agreement would be needed between the two companies because of the shared ownership of the inner circle. A tender was announced for an electric system, and the largest European and American companies applied to win the tender. However, when the experts of the London Metro compared the design of the Ganz Works to the offers of the other large European and American competitors, they have found, that the newest type of AC traction technology of the Ganz Works is more reliable, cheaper and considered its technology as a "revolution in electric railway traction".[43] In 1901 a Metropolitan and District joint committee recommended the Ganz three-phase AC system with overhead wires. Initially this was accepted by both parties,[44] until the District found an investor, the American Charles Yerkes, to finance the upgrade. Yerkes raised £1 million (1901 pounds adjusted by inflation are £109 million) and soon had control of the District Railway.[45] His experiences in the United States led him to favour the classic traditional DC system similar to that in use on the City & South London Railway and Central London Railway. The Metropolitan Railway protested about the change of plan, but after arbitration by the Board of Trade the DC system was adopted.[46]

The Metropolitan electrified its new line from Harrow to Uxbridge and the route to the inner circle at Baker Street,[46] using separate positive and negative conductor rails energised at 550–600 V.[47] The District electrified its unopened line from Mill Hill Park (now Acton Town) to South Harrow and used this line to test its new trains and train drivers.[48] Electric multiple units began running on the Metropolitan in January 1905 and by March all local services between Baker Street and Harrow were electric.[49] Electric services began on the District Railway in June 1905 between Hounslow and South Acton.[50] In July 1905 the District began running electric trains from Ealing to Whitechapel and on the same day the Met and the District both introduced electric units on the inner circle until later that day an incompatibility was found between the way the shoe-gear was mounted on the Met trains and the District track. The Met trains were withdrawn from the District lines and modified, full electric service starting on the circle line in September.[51][52] In the same month, after withdrawing services over the un-electrified East London Railway and east of East Ham, the District were running electric services on all remaining routes.[53] The GWR electrified the line between Paddington and Hammersmith and the branch from Latimer Road to Kensington (Addison Road). An electric service with jointly owned rolling stock started on the route in November 1906.[54] In the same year, the Met suspended running on the East London Railway, terminating instead at the District's station at Whitechapel.[55] The Metropolitan Railway beyond Harrow was not electrified so services were hauled by an electric locomotive from Baker Street and changed for a steam locomotive en route.[46]

The Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway, was authorised from Charing Cross to Hampstead and Highgate in 1893, but had not found financial backing. Yerkes bought the rights in 1900, and obtained additional approval for a branch from Camden Town to Golders Green.[56] The Baker Street and Waterloo Railway had been authorised to run from Baker Street to Waterloo station.[57] Work began in 1898, and extensions to Paddington station and Elephant & Castle were authorised in 1900, but came to a halt with the collapse of their financial backers in 1901. Yerkes bought the rights to this railway in 1902.[56] The District had permission for a deep-level tube from Earl's Court to Mansion House and in 1898 had bought the Brompton and Piccadilly Circus Railway that had authority for a tube from South Kensington to Piccadilly Circus. The District's plans were combined by Yerkes with those of the Great Northern and Strand Railway, a tube railway with permission to build a line from Strand to Finsbury Park, to create the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway.[58] In April 1902, the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) was established, with Yerkes as chairman, to control these companies and manage the planned works.[56]

On 8 June 1902, the UERL took over the Metropolitan District Traction Company.[59] The UERL built a large power station that would be capable of providing power for the District and underground lines under construction. Work began in 1902 at Lots Road, by Chelsea Creek, and in February 1905 Lots Road Power Station began generating electricity.[60] For the three lines similar electric multiple units were purchased, known as "Gate Stock" as access to the cars was via lattice gates at each end operated by gatemen.[61] As on the District Railway the track was provided with separate positive and negative conductor rails, in what was to become a London Underground standard.[62] A number of the surface buildings, with an exterior of glazed dark red bricks, were designed by Leslie Green and 140 electric lifts were imported from America from the Otis Elevator Company.[62] A length of the Baker Street & Waterloo between Baker Street and Kennington Road (now Lambeth North) opened in March 1906, and the line reached Edgware Road the following year. It was named the 'Bakerloo' in July 1906, called an undignified "gutter title" by The Railway Magazine.[56] The Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (the Piccadilly) opened from Finsbury Park to Hammersmith in December 1906, the Aldwych branch opening the following year.[56] "Moving staircases" or escalators were first installed at Earl's Court between the District and Piccadilly line platforms, and at all deep level tube stations after 1912.[63] The last, the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead (the Hampstead) opened in 1907, and ran from Charing Cross to Camden Town, before splitting into two branches going to Golders Green and Highgate (now Archway).[56][64]

To promote travel by the underground railways in London a joint marketing arrangement was agreed that included maps, joint publicity and through ticketing. UNDERGROUND signs were used outside stations in Central London.[65] The UERL acquired London bus and tram companies in 1912 and the following year the City & South London and Central London Railway joined the company. That year the Great Northern & City was taken over by the Met.[63] Suggestions of merger with the Underground Group were rejecte

Lesbian Office Seduction

Arras Io Beta Tester Private Server

Video Porno Lesbians Kuni

Femdom Dougan Com

Wife Ass Rape

History of the London Underground - Wikipedia

A brief history of the Underground - Transport for Lo…

London Underground - Wikipedia

Timeline of the London Underground - Wikipedia

London Underground - Transport for London

A history of the London Underground - CBBC Newsround

First Day of the London Tube | History Today

A Brief History of the London Underground

When Was The London Tube Opened

.jpg)

_edit.jpg)