What do you meme? — shit you should care about

Carlos TkaczLET’S TALK ABOUT MEMES: SPECIFICALLY ABOUT THEIR USE IN POLITICAL CONVERSATION.

Most memes, I think, engage in a laundry list of logical fallacies:

- hasty generalization,

- false analogy,

- false dichotomy,

- oversimplification,

- ad hominem (of an argument or reaction directed against a person rather than the position they are maintaining.),

- strawman (an intentionally misrepresented proposition that is set up because it is easier to defeat than an opponent's real argument.),

- appeal to ignorance,

- red herring (a clue or piece of information which is or is intended to be misleading or distracting),

- tu quoque, (Latin for "you also", or the appeal to hypocrisy, intends to discredit the opponent's argument by asserting their failure to act consistently in accordance with their conclusions.) Bacially calling them a hypocrite.

And this list doesn’t even take into account that memes are often just plain false and hinge on incorrect information).

The fact is that most of the social issues that affect us as individuals and as a society are complex, multi-faceted, and, frankly, overwhelmingly difficult to understand let alone address. The appeal of the meme, then, comes from the way they seem to take these complexities and distill their essences into easily digestible and communicable statements and claims.

However, I would argue that this process comes at a cost that greatly outweighs any benefit and that using memes in any capacity beyond simple humor is a grave hindrance to true understanding and communication, the pillars of any democratic society.

First of all, let’s look at communication in general.(And I am operating under the idea that, if we want to move past the ideological and political gridlock that we seem to have fallen into, we will have to work together and that being able to communicate our ideas effectively to one another is necessary for that).

All communication hinges on the idea of “shared meaning.” At a simple level, this means that when we talk with each other, we use language and words of which the meanings are mutually understood.

Even at the base level of words, this is problematic. Someone who grew up in the tropics likely will have a different image in mind when they hear the word “tree” than someone that grew up in the mountains. Imagine how much more complicated this discrepancy becomes when we consider abstract concepts like “justice” and “equality” and “progress.”

The fact that we each bring our own definitions and images into any conversation involving these things (truly, into any conversation at all) is not something to be leaned into but something to be guarded against — if “shared meaning” is the foundation of and essential for communication, then the first step in any discussion is to lay the groundwork for that sharing.

The responsibility for this falls on both the sender and receiver, as, in any discussion, we are both at the same time. In a discussion, you are constantly switching roles, at one moment the receiver, listening to the information being shared by the other person, and at the next moment the sender, giving your information. For this process to work, both parties have to be receptive to the information; this means that, when you are listening, you have to be willing to listen but, more controversial these days (though I am not quite sure why), when you are speaking, you have to present the information in a way that inclines your listener towards receptiveness.

A CASE FOR POLITICAL CORRECTNESS

I sense that there will be some push back at this idea (it is often lambasted as “political correctness” or “sugar-coating”), so allow me a moment to try and make a case for it. This is called “audience centered” speaking; if the goal is to communicate an idea (especially to an audience that may not agree with that idea from the outset), then the way in which that idea is communicated must take the audience into account.

This is not to say that you should lie or distort your ideas in order to make them more palatable; rather, we should seek to communicate our ideas in a way that our intended audience can relate to, understand, and be willing to consider (again, this is assuming that communication is the goal; I know that is not always the goal for some people).

If we insult our intended audience, what are the chances that they will be willing to listen, now or in the future?

If we treat them without respect, why should they consider our ideas?

If we treat them as if they are stupid by over-simplifying complex ideas, why should they value our input?

If we hinder our own argument by falling into logical fallacies, knowingly or otherwise, how can our audience trust us?

If we present our argument in a way that devalues or negates their own personal experiences, how can they ever relate to our perspective?

If we do not give them the decency of accepting that they, ultimately, have to decide for themselves their own position, why should we expect them to consider us equals in discussion?

The fact is that any claim presented in a way that is not audience centered is not, then, a good-faith attempt at argument or discussion; rather, it is just ego-stroking, the communication equivalent of masturbation.

WHERE MEMES FAIL

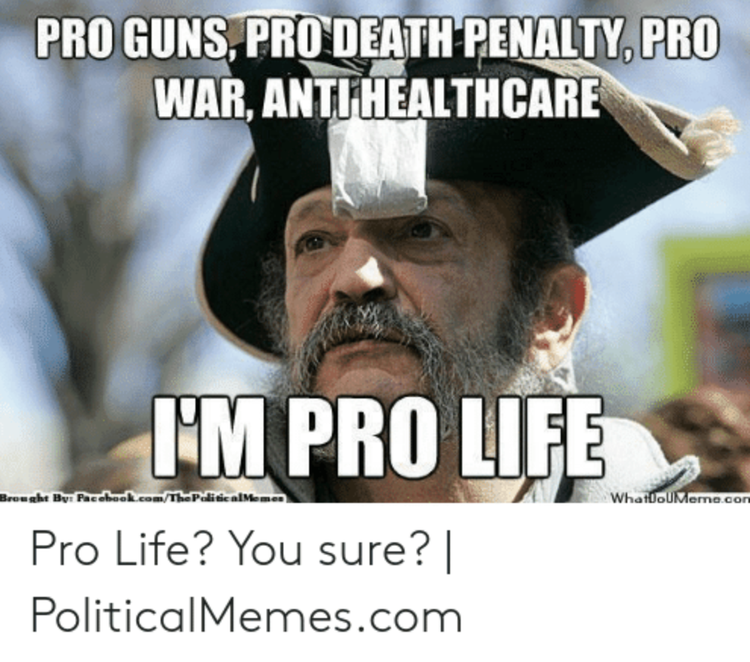

I think memes fail, inherently, to achieve any of the necessary conditions for actual communication. Perhaps the best way to examine this is through an actual meme. I have chosen a liberal meme, as the failures of communication are not solely on one side of the political divide and, as I am fairly liberal in my thinking, to avoid any potential conflict of interest.

First, is there really any chance that any conservative who looks at this will be in any way willing to continue any sort of discussion?

This meme essentially calls conservatives hypocrites, immediately insulting a large group of people and committing the tu quoque fallacy. Pointing out hypocrisy, even if it is true, is not a useful tactic as it usually does not address the actual issue(s) and rather deflects attention away from them.

Also, let’s be fair — we are all hypocrites in one way or another if you look closely enough. Expecting people to be completely non-hypocritical is like expecting them to not be people — the fact is that people are complex and multifaceted, the issues are complex and multi-faceted, and a certain amount of paradox is always going to be a part of any attempt at civil society.

The next obvious fallacy here is oversimplification.

The issues related to the second amendment, to capital punishment, to international relations, to healthcare, and to abortion are huge and complex; this meme makes no attempt to specify or define what it is actually talking about. It does not take into account, say, that, for many conservatives, the second amendment is not about killing, or taking life, but about defending it — essentially pro-life if one accepts that tack.

There is, of course, a hasty generalization here. To assume that all conservatives, or even a majority of them, share ideas on all these issues is a major assumption. For example, many people in my family are opposed to abortion rights but are also open to the idea of stricter gun regulations and are opposed to the death penalty. By the same token, there are many liberals that support abortion rights but that are also gun owners and endorse privatized healthcare. Then there is the image, which commits its own fallacies: it is something of an ad hominem, using an image that paints conservatives as old-fashioned and out of time/place. The image also something of a strawman, though this might be a stretch: it is easy for those that do not see the value of civil war reenactments (I could be wrong about what this person is addressing) to dismiss the ideas of someone that does — the image plays into the differences between liberals and conservatives. Now, while this is by no means an exhaustive list of the problems with this meme, I hope this gives you an idea of how useless it really is.

Let’s stop pretending that memes are a useful tool for politics (which is inherently cooperative and therefore requires communication) and that our use of memes is an attempt to get a conversation started. Let’s start calling memes what they actually are: ego-stroking preaching to the choir that makes no actual attempt at good-faith communication but rather seeks to insult others and sow division by engaging in lazy thinking through the replacement of intelligent and thorough thought with shallow cleverness by letting others (usually anonymous people) do our thinking and talking for us.

Now, this is an attempt to call out the use of memes, but this applies to myself as well. I am not immune to their trappings and appeal, and I have used them before, making the claim that I was “just kidding” or “just trying to get a discussion started” when all I was really doing was trying to feel superior in a world that confuses and scares the shit out of me. The fact is that, regardless of our personal positions and opinions, we all need each other if we want to live in anything resembling civilization (I think, for me, the current pandemic and economic fallout has really hammered this home). At the very least, we have to live with each other. And for this to work, we have to (re)learn to talk and listen to one another.

Carlos Tkacz