Vulgar Latin

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For obscene or "vulgar" Latin words, see Latin obscenity .

This article needs additional citations for verification . Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources . Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Vulgar Latin" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR ( October 2012 ) ( Learn how and when to remove this template message )

^ In a few isolated masculine nouns, the s has been either preserved or reinstated in the modern languages, for example FILIUS ("son") > French fils , DEUS ("god") > Spanish dios and Portuguese deus , and particularly in proper names: Spanish Carlos , Marcos , in the conservative orthography of French Jacques , Charles , Jules , etc. [33]

^ (Herman 2000: 7)

^ Elcock 1960: 20

^ Eskhult 2018: §6

^ Posner 1996: 3

^ Herman 2000: 1

^ Elcock 1960: 21

^ Grandgent 1907: 2–3

^ Wright 2002: 27–28; Pei 1941: 16, 23

^ Treadgold 1997: 184–217, 276

^ Treadgold 1997: 221–224, 290, 293. The combined Slavic-Avar invasion proved especially disruptive, as it isolated Latin speakers in the interior of the Balkans from their western counterparts for more than a millennium (Nandris 1951: 15).

^ Treadgold 1997: 310, 337–339, 371–372

^ Carlton 1973: 237. According to Pei & Gaeng (1976: 76–81), the decisive moment came with the Islamic conquest of North Africa and Iberia, which was followed by numerous raids on land and by sea. All this had the effect of disrupting connections between the western Romance-speaking regions.

^ Herman 2000: 117

^ Adams 2007: 660–670

^ Alkire & Rosen 2010: 287

^ Herman 2000: 2

^ Harrington et al. 1997: 11

^ Harrington et al. 1997: 7–10

^ Pope 1934: §156.2

^ Hall 1976: 180

^ Allen 1965: 27–29

^ Gouvert 2015: 83

^ Pope 1934: §155; Gouvert 2016: 48

^ Grandgent 1907: §267; Pope 1934: §156.3

^ Grandgent 1907: §226; Pope 1934: §187.b

^ Grandgent 1907: §255

^ Palmer 1988: 157

^ Leppänen & Alho 2018: 21–22

^ Adams 2013: 60–1, 67

^ Adams 2007: 626–9

^ Jump up to: a b c Vincent (1990).

^ Jump up to: a b Harrington et al. (1997).

^ Menéndez Pidal 1968, p. 208; Survivances du cas sujet .

^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Herman 2000 , p. 52.

^ Jump up to: a b c Grandgent 1991 , p. 82. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGrandgent1991 ( help )

^ Captivi , 1019.

^ Jump up to: a b c Herman 2000 , p. 53.

^ Romanian Explanatory Dictionary ( DEXOnline.ro )

^ Jump up to: a b Grandgent 1991 , p. 238. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGrandgent1991 ( help )

General

Adams, J. N. (2007). The Regional Diversification of Latin . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Adams, James Noel (2013). Social variation and the Latin language . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alkire, Ti (2010). Romance Languages: A Historical Introduction . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Allen, W. Sidney (1965). Vox Latina – a Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press . ISBN 0-521-37936-9 .

Boyd-Bowman, Peter (1980). From Latin to Romance in Sound Charts . Washington DC: Georgetown University Press.

Carlton, Charles Merritt. 1973. A linguistic analysis of a collection of Late Latin documents composed in Ravenna between A.D. 445–700 . The Hague: Mouton.

Diez, Friedrich (1882). Grammatik der romanischen Sprachen (in German) (5th ed.). Bonn: E. Weber.

Elcock, W. D. (1960). The Romance Languages . London: Faber & Faber.

Eskhult, Josef (2018). "Vulgar Latin as an emergent concept in the Italian Renaissance (1435–1601): its ancient and medieval prehistory and its emergence and development in Renaissance linguistic thought" . Journal of Latin Linguistics . 17 (2): 191–230. doi : 10.1515/joll-2018-0006 .

Grandgent, C. H. (1907). An Introduction to Vulgar Latin . Boston: D.C. Heath.

Gouvert, Xavier. 2016. Du protoitalique au protoroman: Deux problèmes de reconstruction phonologique. In: Buchi, Éva & Schweickard, Wolfgang (eds.), Dictionnaire étymologique roman 2, 27–51. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Hall, Robert A., Jr. (1950). "The Reconstruction of Proto-Romance". Language . 26 (1): 6–27. doi : 10.2307/410406 . JSTOR 410406 .

Hall, Robert Anderson (1976). Proto-Romance Phonology . New York: Elsevier.

Harrington, K. P.; Pucci, J.; Elliott, A. G. (1997). Medieval Latin (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press . ISBN 0-226-31712-9 .

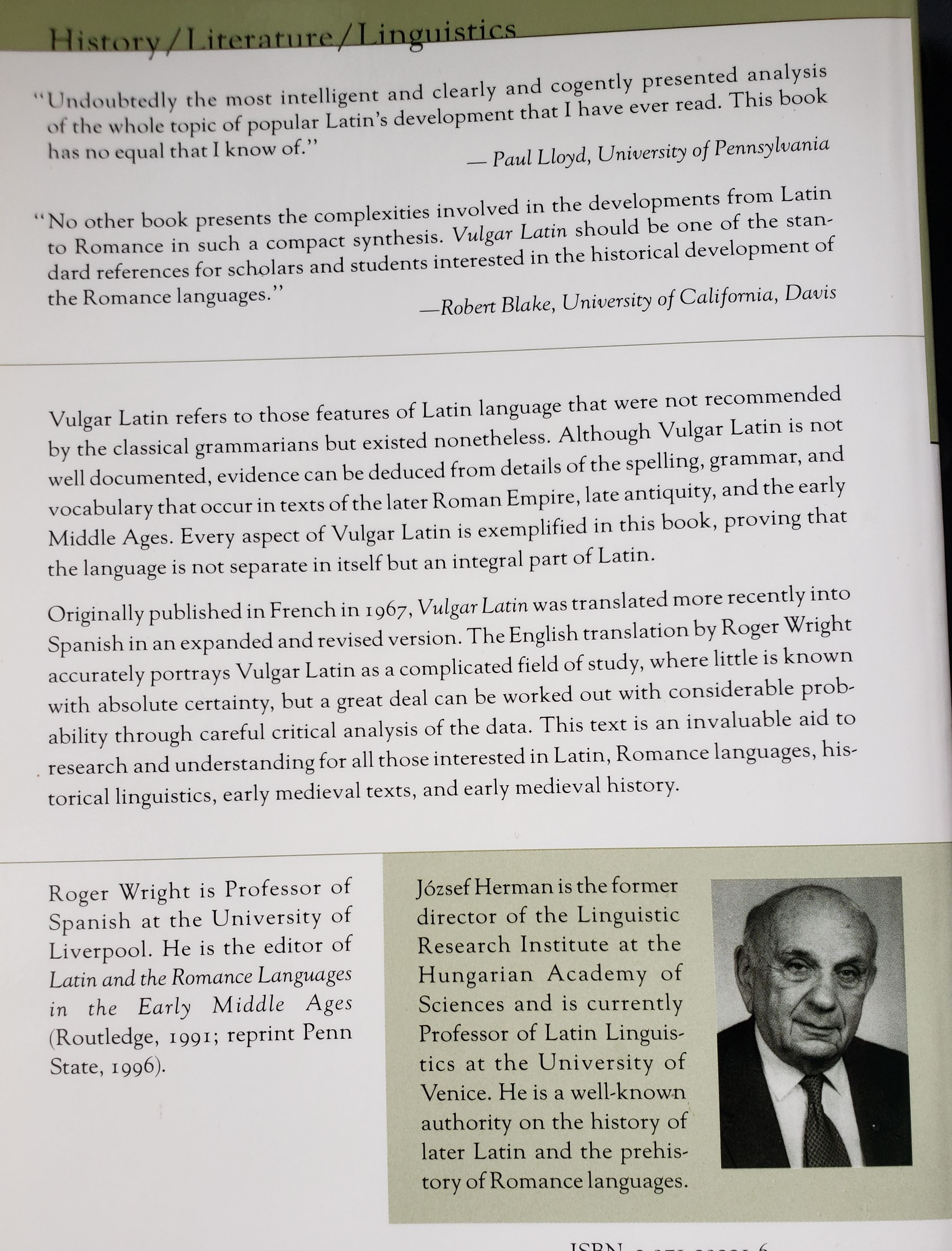

Herman, József (2000). Vulgar Latin . Translated by Wright, Roger. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press . ISBN 0-271-02001-6 .

Johnson, Mark J. (1988). "Toward a History of Theoderic's Building Program". Dumbarton Oaks Papers . 42 : 73–96. doi : 10.2307/1291590 . JSTOR 1291590 .

Leppänen, V., & Alho, T. 2018. On the mergers of Latin close-mid vowels. Transactions of the Philological Society 116. 460–483.

Lloyd, Paul M. (1979). "On the Definition of 'Vulgar Latin': The Eternal Return". Neuphilologische Mitteilungen . 80 (2): 110–122. JSTOR 43343254 .

Meyer, Paul (1906). "Beginnings and Progress of Romance Philology". In Rogers, Howard J. (ed.). Congress of Arts and Sciences: Universal Exposition, St. Louis, 1904 . Volume III. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. pp. 237–255. |volume= has extra text ( help )

Nandris, Grigore. 1951. The development and structure of Rumanian. The Slavonic and East European Review , 30. 7-39.

Palmer, L. R. (1988) [1954]. The Latin Language . University of Oklahoma. ISBN 0-8061-2136-X .

Pei, Mario. 1941. The Italian language . New York: Columbia University Press.

Pei, Mario & Gaeng, Paul A. 1976. The story of Latin and the Romance languages . New York: Harker & Row.

Pulgram, Ernst (1950). "Spoken and Written Latin". Language . 26 (4): 458–466. doi : 10.2307/410397 . JSTOR 410397 .

Posner, Rebecca (1996). The Romance Languages . Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sihler, A. L. (1995). New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin . Oxford: Oxford University Press . ISBN 0-19-508345-8 .

Treadgold, Warren. 1997. A history of the Byzantine state and society . Stanford University Press.

Tucker, T. G. (1985) [1931]. Etymological Dictionary of Latin . Ares Publishers. ISBN 0-89005-172-0 .

Väänänen, Veikko (1981). Introduction au latin vulgaire (3rd ed.). Paris: Klincksieck. ISBN 2-252-02360-0 .

Vincent, Nigel (1990). "Latin". In Harris, M.; Vincent, N. (eds.). The Romance Languages . Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-520829-3 .

von Wartburg, Walther; Chambon, Jean-Pierre (1922–1967). Französisches etymologisches Wörterbuch: eine Darstellung des galloromanischen Sprachschatzes (in German and French). Bonn: F. Klopp.

Wright, Roger (1982). Late Latin and Early Romance in Spain and Carolingian France . Liverpool: Francis Cairns.

Wright, Roger (2002). A Sociophilological Study of Late Latin . Utrecht: Brepols.

To Romance in general

Banniard, Michel (1997). Du latin aux langues romanes . Paris: Nathan.

Bonfante, Giuliano (1999). The origin of the Romance languages: Stages in the development of Latin . Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

Ledgeway, Adam (2012). From Latin to Romance: Morphosyntactic Typology and Change . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin, eds. (2016). The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages. Part 1: The Making of the Romance Languages . Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam, eds. (2013). The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages. Volume II: Contexts . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. (esp. parts 1 & 2, Latin and the Making of the Romance Languages ; The Transition from Latin to the Romance Languages )

Wright, Roger (1982). Late Latin and Early Romance in Spain and Carolingian France . Liverpool: Francis Cairns.

Wright, Roger, ed. (1991). Latin and the Romance Languages in the Early Middle ages . London/New York: Routledge.

To French

Ayres-Bennett, Wendy (1995). A History of the French Language through Texts . London/New York: Routledge.

Kibler, William W. (1984). An Introduction to Old French . New York: Modern Language Association of America.

Lodge, R. Anthony (1993). French: From Dialect to Standard . London/New York: Routledge.

Pope, Mildred K. (1934). From Latin to Modern French with Especial Consideration of Anglo-Norman Phonology and Morphology . Manchester: Manchester University Press .

Price, Glanville (1998). The French language: present and past (Revised ed.). London, England: Grant and Cutler.

To Italian

Maiden, Martin (1996). A Linguistic History of Italian . New York: Longman.

Vincent, Nigel (2006). "Languages in contact in Medieval Italy". In Lepschy, Anna Laura (ed.). Rethinking Languages in Contact: The Case of Italian . Oxford and New York: LEGENDA (Routledge). pp. 12–27.

To Spanish

Lloyd, Paul M. (1987). From Latin to Spanish . Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

Penny, Ralph (2002). A History of the Spanish Language . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Pharies, David A. (2007). A Brief History of the Spanish Language . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pountain, Christopher J. (2000). A History of the Spanish Language Through Texts . London, England: Routledge.

To Portuguese

Castro, Ivo (2004). Introdução à História do Português . Lisbon: Edições Colibri.

Emiliano, António (2003). Latim e Romance na segunda metade do século XI . Lisbon: Fundação Gulbenkian.

Williams, Edwin B. (1968). From Latin to Portuguese: Historical Phonology and Morphology of the Portuguese Language . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

To Occitan

Paden, William D. (1998). An Introduction to Old Occitan . New York: Modern Language Association of America.

To Sardinian

Blasco Ferrer, Eduardo (1984). Storia linguistica della Sardegna . Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Wiki Loves Monuments: your chance to support Russian cultural heritage!

Photograph a monument and win!

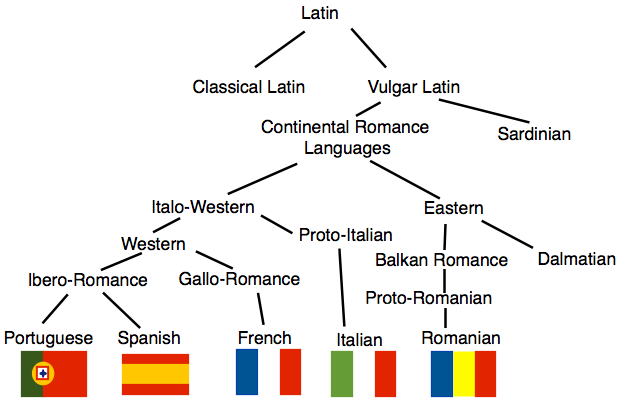

Vulgar Latin , also known as Popular or Colloquial Latin , is non- literary Latin spoken from the Late Roman Republic onwards. [1] Depending on the time period, its literary counterpart was either Classical Latin or Late Latin .

During the Classical period , Roman authors referred to the informal, everyday variety of their own language as sermo plebeius or sermo vulgaris , meaning "common speech". [2]

The modern usage of the term Vulgar Latin dates to the Renaissance , when Italian thinkers began to theorize that their own language originated in a sort of "corrupted" Latin that they assumed formed an entity distinct from the literary Classical variety, though opinions differed greatly on the nature of this "vulgar" dialect. [3]

The early 19th-century French linguist Raynouard is often regarded as the father of modern Romance philology . Observing that the Romance languages have many features in common that are not found in Latin, at least not in "proper" or Classical Latin, he concluded that the former must have all had some common ancestor (which he believed most closely resembled Old Occitan ) that replaced Latin some time before the year 1000. This he dubbed la langue romane or "the Roman language". [4]

The first truly modern treatise on Romance linguistics, however, and the first to apply the comparative method , was Friedrich Christian Diez 's seminal Grammar of the Romance Languages . [5]

Evidence for the features of non-literary Latin comes from the following sources: [6]

By the end of the first century AD the Romans had conquered the entire Mediterranean Basin and established hundreds of colonies in the conquered provinces. Over time this—along with other factors that encouraged linguistic and cultural assimilation , such as political unity, frequent travel and commerce, military service, etc.—made Latin the predominant language throughout the western Mediterranean. [7] Latin itself was subject to the same assimilatory tendencies, such that its varieties had probably become more uniform by the time the Western Empire fell in 476 than they had been before it. That is not to say that the language had been static for all those years, but rather that ongoing changes tended to spread to all regions. [8]

All of these homogenizing factors were disrupted or voided by a long string of calamities. Although Justinian succeeded in reconquering Italy , Africa , and the southern part of Iberia in the period 533–554, the Empire was hit by one of the deadliest plagues in recorded history in 541, one that would recur six more times before 610. [9] Under his successors most of the Italian peninsula was lost to the Lombards by c. 572, most of southern Iberia to the Visigoths by c. 615, and most of the Balkans to the Slavs and Avars by c. 620. [10] All this was possible due to Roman preoccupation with wars against Persia , the last of which lasted nearly three decades and exhausted both empires. Taking advantage of this, the Arabs invaded and occupied Syria and Egypt by 642, greatly weakening the Empire and ending its centuries of domination over the Mediterranean. [11] They went on to take the rest of North Africa by c. 699 and soon invaded the Visigothic Kingdom as well, seizing most of Iberia from it by c. 716.

It is from approximately the seventh century onward that regional differences proliferate in the language of Latin documents, indicating the fragmentation of Latin into the incipient Romance languages. [12] Until then Latin appears to have been remarkably homogenous, as far as can be judged from its written records, [13] although careful statistical analysis reveals regional differences in the treatment of the Latin vowel /ĭ/ and in the progression of betacism by about the fifth century. [14]

Over the centuries, spoken Latin lost various lexical items and replaced them with native coinages ; with borrowings from neighbouring languages such as Gaulish , Germanic , or Greek ; or with other native words that had undergone semantic shift . The literary language generally retained the older words, however.

A textbook example is the general replacement of the suppletive Classical verb ferre , meaning 'carry', with the regular portare . [15] Similarly, the Classical loqui , meaning 'speak', was replaced by a variety of alternatives such as the native fabulari and narrare or the Greek borrowing parabolare . [16]

Classical Latin particles fared especially poorly, with all of the following vanishing from popular speech: an , at , autem , donec , enim , etiam , haud , igitur , ita , nam , postquam , quidem , quin , quoad , quoque , sed , sive , utrum , and vel . [17]

Many surviving words experienced a shift in meaning. Some notable cases are civitas ('citizenry' → 'city', replacing urbs ); focus ('hearth' → 'fire', replacing ignis ); manducare ('chew' → 'eat', replacing edere ); causa ('subject matter' → 'thing', competing with res ); mittere ('send' → 'put', competing with ponere ); necare ('murder' → 'drown', competing with submergere ); pacare ('placate' → 'pay', competing with solvere ), and totus ('whole' → 'all, every', competing with omnis ). [18]

Front vowels in hiatus (after a consonant and before another vowel) became [j], which palatalized preceding consonants. [22]

/w/ (except after /k/) and intervocalic /b/ merge as the bilabial fricative /β/. [23]

The system of phonemic vowel length collapsed by the fifth century AD, leaving quality differences as the distinguishing factor between vowels; the paradigm thus changed from /ī ĭ ē ĕ ā ă ŏ ō ŭ ū/ to /i ɪ e ɛ a ɔ o ʊ u/. Concurrently, stressed vowels in open syllables lengthened . [28]

Towards the end of the Roman Empire /ɪ/ merged with /e/ in most regions, [29] although not in Africa or a few peripheral areas in Italy. [30]

It is difficult to place the point in which the definite article , absent in Latin but present in all Romance languages, arose, largely because the highly colloquial speech in which it arose was seldom written down until the daughter languages had strongly diverged; most surviving texts in early Romance show the articles fully developed.

Definite articles evolved from demonstrative pronouns or adjectives (an analogous development is found in many Indo-European languages, including Greek , Celtic and Germanic ); compare the fate of the Latin demonstrative adjective ille , illa , illud "that", in the Romance languages , becoming French le and la (Old French li , lo , la ), Catalan and Spanish el , la and lo , Occitan lo and la , Portuguese o and a (elision of -l- is a common feature of Portuguese) and Italian il , lo and la . Sardinian went its own way here also, forming its article from ipse , ipsa "this" ( su, sa ); some Catalan and Occitan dialects have articles from the same source. While most of the Romance languages put the article before the noun, Romanian has its own way, by putting the article after the noun, e.g. lupul ("the wolf" – from * lupum illum ) and omul ("the man" – *homo illum ), [31] possibly a result of being within the Balkan sprachbund .

This demonstrative is used in a number of contexts in some early texts in ways that suggest that the Latin demonstrative was losing its force. The Vetus Latina Bible contains a passage Est tamen ille daemon sodalis peccati ("The devil is a companion of sin"), in a context that suggests that the word meant little more than an article. The need to translate sacred texts that were originally in Koine Greek , which had a definite article, may have given Christian Latin an incentive to choose a substitute. Aetheria uses ipse similarly: per mediam vallem ipsam ("through the middle of the valley"), suggesting that it too was weakening in force. [32]

Another indication of the weakening of the demonstratives can be inferred from the fact that at this time, legal and similar texts begin to swarm with praedictus , supradictus , and so forth (all meaning, essentially, "aforesaid"), which seem to mean little more than "this" or "that". Gregory of Tours writes, Erat autem... beatissimus Anianus in supradicta civitate episcopus ("Blessed Anianus was bish

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vulgar_Latin

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Vulgar-Latin

Teens 10 Y O

Panty Pantyhose Upskirt

Horny Granny Porn

Vulgar Latin - Wikipedia

Vulgar Latin | language | Britannica

Vulgar Latin - McGill University School of Computer …

Vulgar Latin: Why Late Latin Was Called Vulgar

Vulgar Latin - Wiktionary

How to say vulgar in Latin - WordHippo

Appendix:Vulgar Latin Swadesh list - Wiktionary

Latin - Wikipedia

Lexical changes from Classical Latin to Proto …

Latin phonology and orthography - Wikipedia

Vulgar Latin

.jpg/220px-Sacramenta_Argentariae_(pars_brevis).jpg)