Vulgar Latin

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vulgar_Latin

Language family: Indo-European, ItalicLatino …

Native to: Roman Empire, Various Roman …

Writing system: Latin

ISO 639-3: –

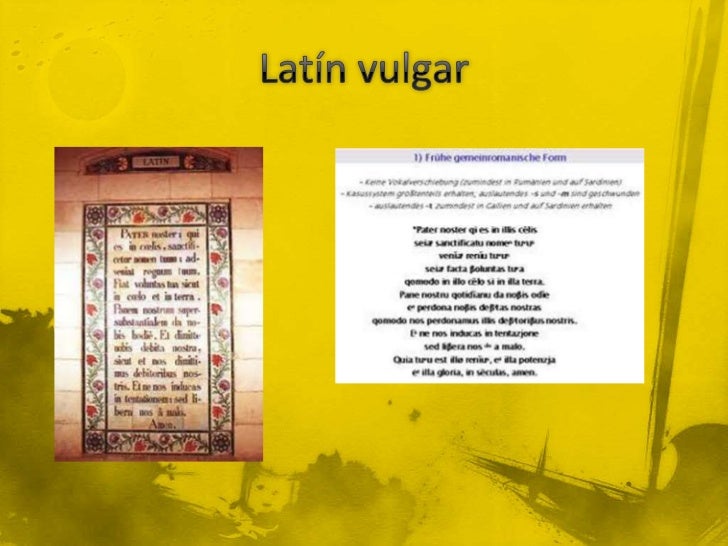

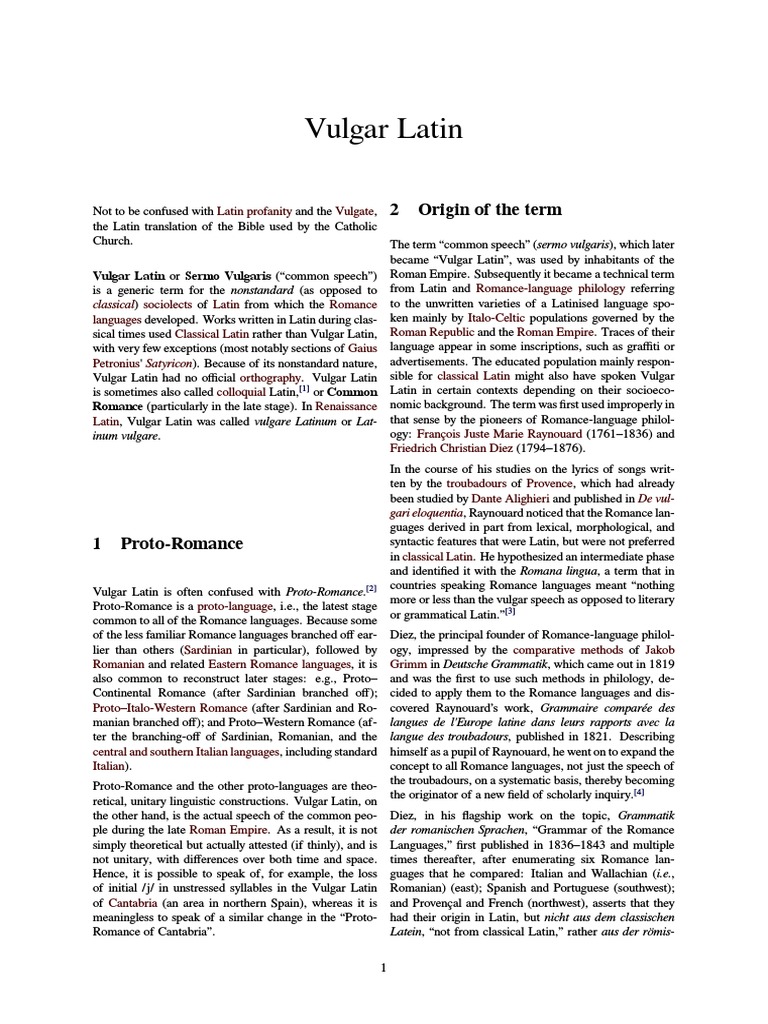

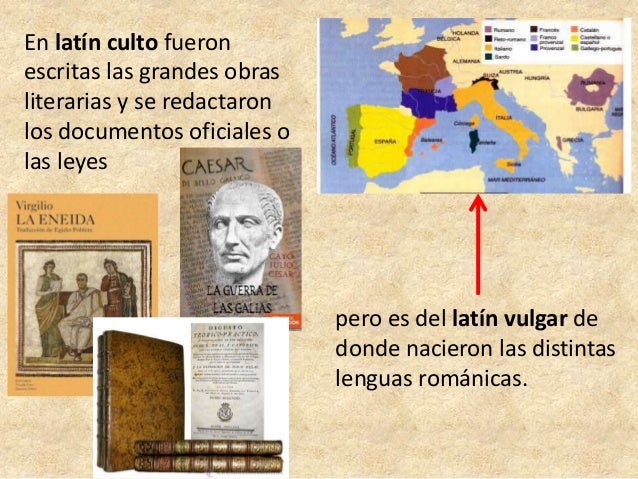

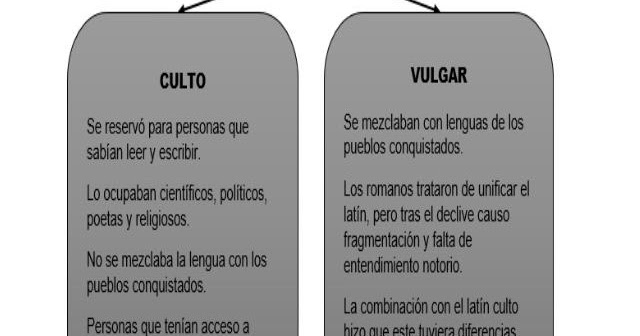

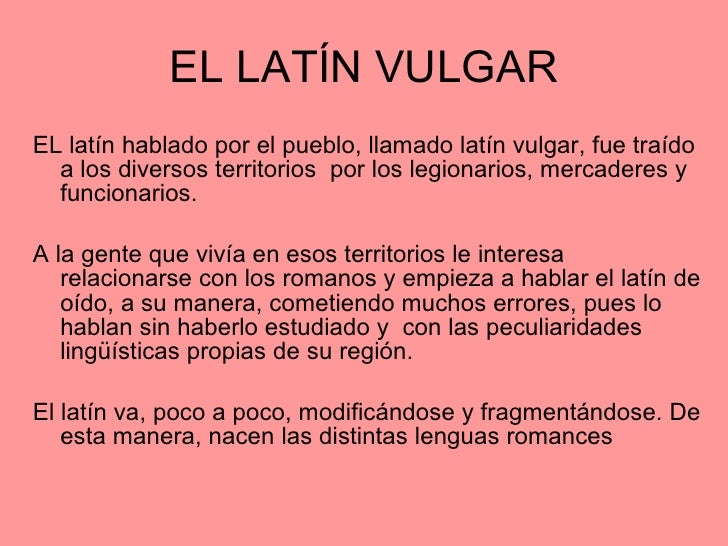

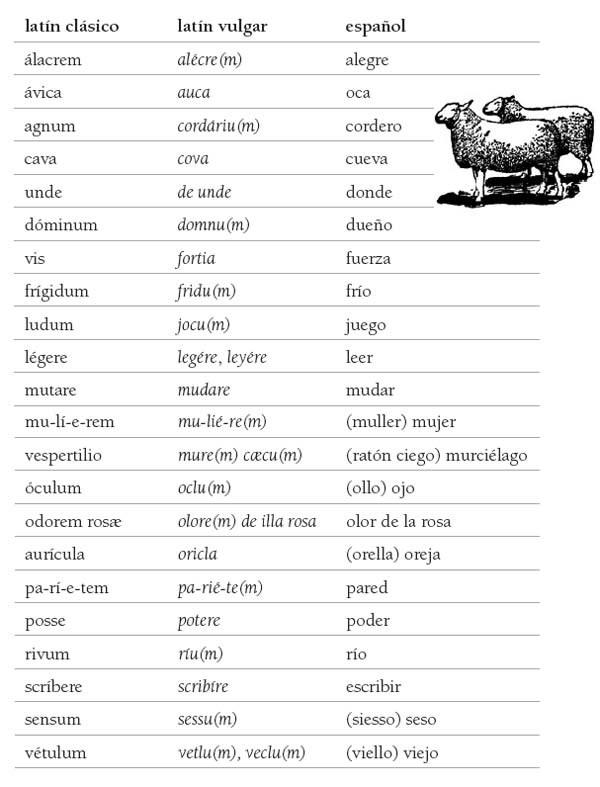

Vulgar Latin, also known as Popular or Colloquial Latin is a range of informal sociolects of Latin spoken as a native language starting in the first century BC, under the late Roman Republic and then the Empire, at first only in Italy and later also in heavily romanized provinces such as Hispania, Gaul, Illyria, Thrace, and Africa. Its more formal and literary counterpart was Classical Latin, the written form of which had been standardized by the b…

Vulgar Latin, also known as Popular or Colloquial Latin is a range of informal sociolects of Latin spoken as a native language starting in the first century BC, under the late Roman Republic and then the Empire, at first only in Italy and later also in heavily romanized provinces such as Hispania, Gaul, Illyria, Thrace, and Africa. Its more formal and literary counterpart was Classical Latin, the written form of which had been standardized by the beginning of this period.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Vulgar-Latin

Перевести · 10.05.2021 · Vulgar Latin, spoken form of non-Classical Latin from which originated the Romance group of languages. Later Latin (from the 3rd century ce onward) …

Народная латынь; известна также как «вульгарная латынь», поздняя латынь и народно-латинский язык — …

Текст из Википедии, лицензия CC-BY-SA

https://context.reverso.net/перевод/английский-русский/vulgar...

In Latin orthography, ae originally represented the diphthong/ai/, before it was monophthongized in the Vulgar Latin period to/ɛ/; in medieval manuscripts, the digraph …

https://www.latinitium.com/blog/what-is-vulgar-latin

Перевести · 23.06.2020 · Vulgar Latin was the Latin of the middle class. It was the Latin of people with some, but limited, schooling: the merchants, artisans, lower public officials …

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_Latin_language

Era: Antiquity; developed into Romance languages …

Language family: Indo-European, ItalicLatino …

Writing system: Latin

ISO 639-3: –

Romance articles

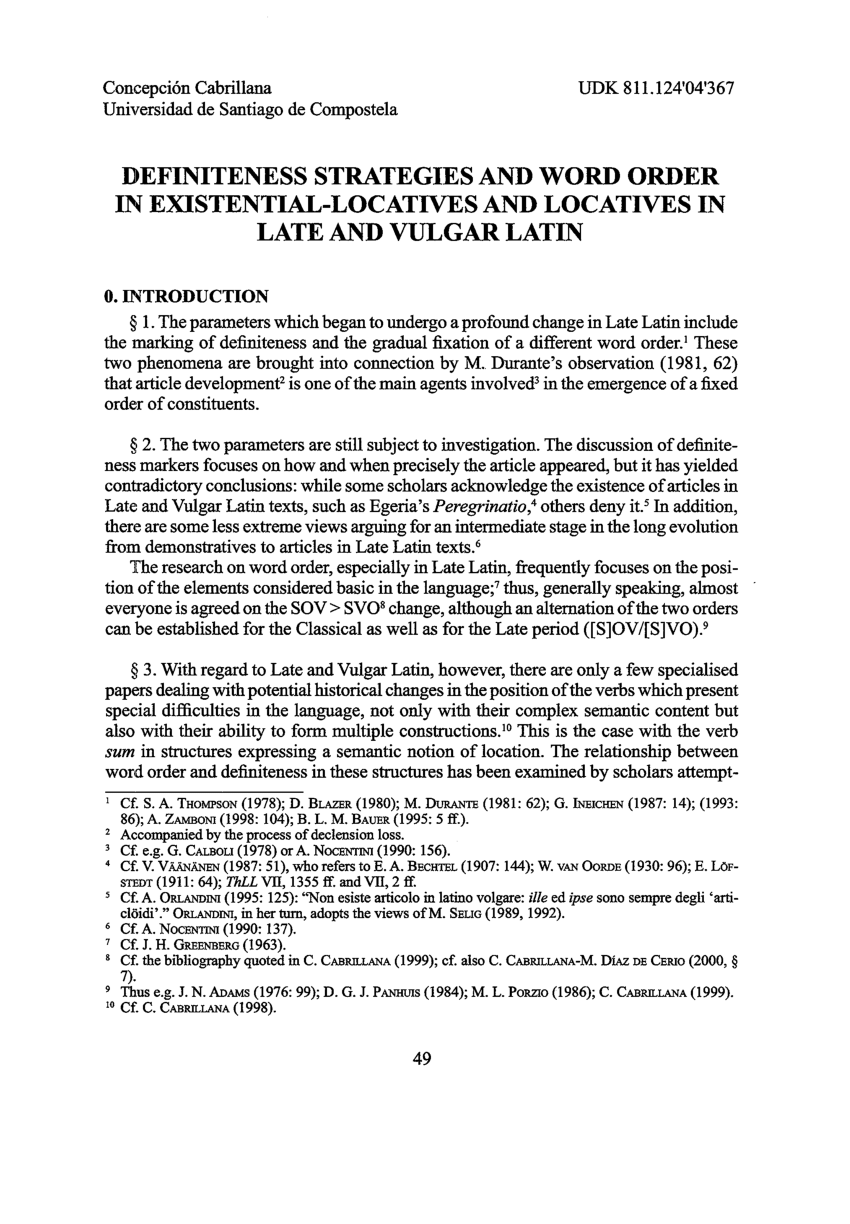

It is difficult to place the point in which the definite article, absent in Latin but present in all Romance languages, arose, largely because the highly colloquial speech in which it arose was seldom written down until the daughter languages had strongly diverged; most surviving texts in early Romance show the articles fully developed.

Definite articles evolved from demonstrative pronouns

Romance articles

It is difficult to place the point in which the definite article, absent in Latin but present in all Romance languages, arose, largely because the highly colloquial speech in which it arose was seldom written down until the daughter languages had strongly diverged; most surviving texts in early Romance show the articles fully developed.

Definite articles evolved from demonstrative pronouns or adjectives (an analogous development is found in many Indo-European languages, including Greek, Celtic and Germanic); compare the fate of the Latin demonstrative adjective ille, illa, illud "that", in the Romance languages, becoming French le and la (Old French li, lo, la), Catalan and Spanish el, la and lo, Occitan lo and la, Portuguese o and a (elision of -l- is a common feature of Portuguese), and Italian il, lo and la. Sardinian went its own way here also, forming its article from ipse, ipsa "this" (su, sa); some Catalan and Occitan dialects have articles from the same source. While most of the Romance languages put the article before the noun, Romanian has its own way, by putting the article after the noun, e.g. lupul ("the wolf" – from *lupum illum) and omul ("the man" – *homo illum), possibly a result of being within the Balkan sprachbund.

This demonstrative is used in a number of contexts in some early texts in ways that suggest that the Latin demonstrative was losing its force. The Vetus Latina Bible contains a passage Est tamen ille daemon sodalis peccati ("The devil is a companion of sin"), in a context that suggests that the word meant little more than an article. The need to translate sacred texts that were originally in Koine Greek, which had a definite article, may have given Christian Latin an incentive to choose a substitute. Aetheria uses ipse similarly: per mediam vallem ipsam ("through the middle of the valley"), suggesting that it too was weakening in force.

Another indication of the weakening of the demonstratives can be inferred from the fact that at this time, legal and similar texts begin to swarm with praedictus, supradictus, and so forth (all meaning, essentially, "aforesaid"), which seem to mean little more than "this" or "that". Gregory of Tours writes, Erat autem... beatissimus Anianus in supradicta civitate episcopus ("Blessed Anianus was bishop in that city.") The original Latin demonstrative adjectives were no longer felt to be strong or specific enough.

In less formal speech, reconstructed forms suggest that the inherited Latin demonstratives were made more forceful by being compounded with ecce (originally an interjection: "behold!"), which also spawned Italian ecco through eccum, a contracted form of ecce eum. This is the origin of Old French cil (*ecce ille), cist (*ecce iste) and ici (*ecce hic); Italian questo (*eccum istum), quello (*eccum illum) and (now mainly Tuscan) codesto (*eccum tibi istum), as well as qui (*eccu hic), qua (*eccum hac); Spanish and Occitan aquel and Portuguese aquele (*eccum ille); Spanish acá and Portuguese cá (*eccum hac); Spanish aquí and Portuguese aqui (*eccum hic); Portuguese acolá (*eccum illac) and aquém (*eccum inde); Romanian acest (*ecce iste) and acela (*ecce ille), and many other forms.

On the other hand, even in the Oaths of Strasbourg, no demonstrative appears even in places where one would clearly be called for in all the later languages (pro christian poblo – "for the Christian people"). Using the demonstratives as articles may have still been considered overly informal for a royal oath in the 9th century. Considerable variation exists in all of the Romance vernaculars as to their actual use: in Romanian, the articles are suffixed to the noun (or an adjective preceding it), as in other languages of the Balkan sprachbund and the North Germanic languages.

The numeral unus, una (one) supplies the indefinite article in all cases (again, this is a common semantic development across Europe). This is anticipated in Classical Latin; Cicero writes cum uno gladiatore nequissimo ("with a most immoral gladiator"). This suggests that unus was beginning to supplant quidam in the meaning of "a certain" or "some" by the 1st century BC.

Loss of neuter gender

The three grammatical genders of Classical Latin were replaced by a two-gender system in most Romance languages.

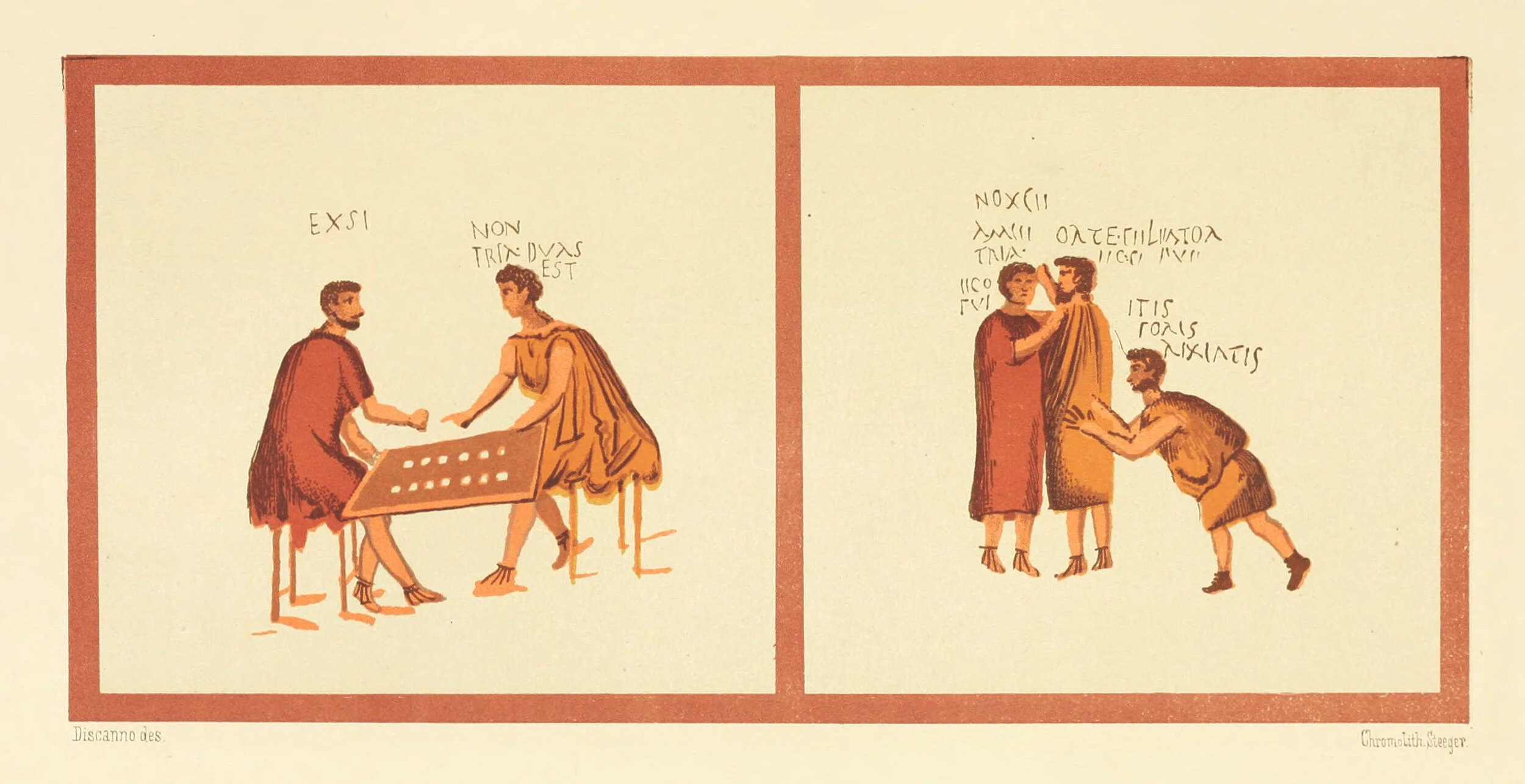

The neuter gender of classical Latin was in most cases identical with the masculine both syntactically and morphologically. The confusion had already started in Pompeian graffiti, e.g. cadaver mortuus for cadaver mortuum ("dead body"), and hoc locum for hunc locum ("this place"). The morphological confusion shows primarily in the adoption of the nominative ending -us (-Ø after -r) in the o-declension.

In Petronius' work, one can find balneus for balneum ("bath"), fatus for fatum ("fate"), caelus for caelum ("heaven"), amphitheater for amphitheatrum ("amphitheatre"), vinus for vinum ("wine"), and conversely, thesaurum for thesaurus ("treasure"). Most of these forms occur in the speech of one man: Trimalchion, an uneducated Greek (i.e. foreign) freedman.

In modern Romance languages, the nominative s-ending has been largely abandoned, and all substantives of the o-declension have an ending derived from -um: -u, -o, or -Ø. E.g., masculine murum ("wall"), and neuter caelum ("sky") have evolved to: Italian muro, cielo; Portuguese muro, céu; Spanish muro, cielo, Catalan mur, cel; Romanian mur, cieru>cer; French mur, ciel. However, Old French still had -s in the nominative and -Ø in the accusative in both words: murs, ciels [nominative] – mur, ciel [oblique]. Template:Efb

For some neuter nouns of the third declension, the oblique stem was productive; for others, the nominative/accusative form, (the two were identical in Classical Latin). Evidence suggests that the neuter gender was under pressure well back into the imperial period. French (le) lait, Catalan (la) llet, Occitan (lo) lach, Spanish (la) leche, Portuguese (o) leite, Italian language (il) latte, Leonese (el) lleche and Romanian lapte(le) ("milk"), all derive from the non-standard but attested Latin nominative/accusative neuter lacte or accusative masculine lactem. In Spanish the word became feminine, while in French, Portuguese and Italian it became masculine (in Romanian it remained neuter, lapte/lăpturi). Other neuter forms, however, were preserved in Romance; Catalan and French nom, Leonese, Portuguese and Italian nome, Romanian nume ("name") all preserve the Latin nominative/accusative nomen, rather than the oblique stem form *nominem (which nevertheless produced Spanish nombre).

Most neuter nouns had plural forms ending in -A or -IA; some of these were reanalysed as feminine singulars, such as gaudium ("joy"), plural gaudia; the plural form lies at the root of the French feminine singular (la) joie, as well as of Catalan and Occitan (la) joia (Italian la gioia is a borrowing from French); the same for lignum ("wood stick"), plural ligna, that originated the Catalan feminine singular noun (la) llenya, and Spanish (la) leña. Some Romance languages still have a special form derived from the ancient neuter plural which is treated grammatically as feminine: e.g., BRACCHIUM : BRACCHIA "arm(s)" → Italian (il) braccio : (le) braccia, Romanian braț(ul) : brațe(le). Cf. also Merovingian Latin ipsa animalia aliquas mortas fuerant.

Alternations in Italian heteroclitic nouns such as l'uovo fresco ("the fresh egg") / le uova fresche ("the fresh eggs") are usually analysed as masculine in the singular and feminine in the plural, with an irregular plural in -a. However, it is also consistent with their historical development to say that uovo is simply a regular neuter noun (ovum, plural ova) and that the characteristic ending for words agreeing with these nouns is -o in the singular and -e in the plural. The same alternation in gender exists in certain Romanian nouns, but is considered regular as it is more common than in Italian. Thus, a relict neuter gender can arguably be said to persist in Italian and Romanian.

In Portuguese, traces of the neuter plural can be found in collective formations and words meant to inform a bigger size or sturdiness. Thus, one can use ovo/ovos ("egg/eggs") and ova/ovas ("roe", "a collection of eggs"), bordo/bordos ("section(s) of an edge") and borda/bordas ("edge/edges"), saco/sacos ("bag/bags") and saca/sacas ("sack/sacks"), manto/mantos ("cloak/cloaks") and manta/mantas ("blanket/blankets"). Other times, it resulted in words whose gender may be changed more or less arbitrarily, like fruto/fruta ("fruit"), caldo/calda (broth"), etc.

These formations were especially common when they could be used to avoid irregular forms. In Latin, the names of trees were usually feminine, but many were declined in the second declension paradigm, which was dominated by masculine or neuter nouns. Latin pirus ("pear tree"), a feminine noun with a masculine-looking ending, became masculine in Italian (il) pero and Romanian păr(ul); in French and Spanish it was replaced by the masculine derivations (le) poirier, (el) peral; and in Portuguese and Catalan by the feminine derivations (a) pereira, (la) perera.

As usual, irregularities persisted longest in frequently used forms. From the fourth declension noun manus ("hand"), another feminine noun with the ending -us, Italian and Spanish derived (la) mano, Romanian mânu>mâna pl (reg.)mânule/mânuri, Catalan (la) mà, and Portuguese (a) mão, which preserve the feminine gender along with the masculine appearance.

Except for the Italian and Romanian heteroclitic nouns, other major Romance languages have no trace of neuter nouns, but still have neuter pronouns. French celui-ci / celle-ci / ceci ("this"), Spanish éste / ésta / esto ("this"), Italian: gli / le / ci ("to him" /"to her" / "to it"), Catalan: ho, açò, això, allò ("it" / this / this-that / that over there); Portuguese: todo / toda / tudo ("all of him" / "all of her" / "all of it").

In Spanish, a three-way contrast is also made with the definite articles el, la, and lo. The last is used with nouns denoting abstract categories: lo bueno, literally "that which is good", from bueno: good.

Loss of oblique cases

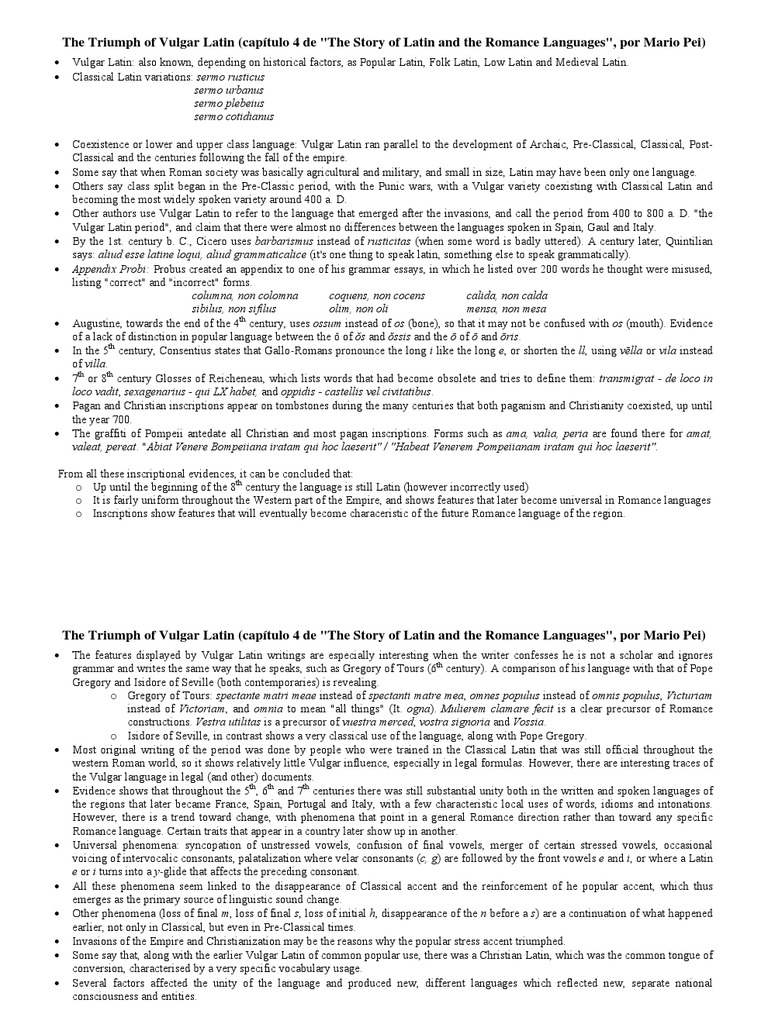

The Vulgar Latin vowel shifts caused the merger of several case endings in the nominal and adjectival declensions. Some of the causes include: the loss of final m, the merger of ă with ā, and the merger of ŭ with ō (see tables). Thus, by the 5th century, the number of case contrasts had been drastically reduced.

There also seems to be a marked tendency to confuse different forms even when they had not become homophonous (like the generally more distinct plurals), which indicates that nominal declension was shaped not only by phonetic mergers, but also by structural factors. As a result of the untenability of the noun case system after these phonetic changes, Vulgar Latin shifted from a markedly synthetic language to a more analytic one.

The genitive case died out around the 3rd century AD, according to Meyer-Lübke, and began to be replaced by de + noun (which originally meant "about/concerning", weakened to "of") as early as the 2nd century BC . Exceptions of remaining genitive forms are some pronouns, many fossilized combinations like sayings, some proper names, and certain terms related to the church. For example, French jeudi ("Thursday") < Old French juesdi < Vulgar Latin jovis diēs; Spanish es menester ("it is necessary") < est ministeri; terms like angelorum, paganorum; and Italian terremoto ("earthquake") < terrae motu as well as names like Paoli, Pieri.

The dative case lasted longer than the genitive, even though Plautus, in the 2nd century BC, already shows some instances of substitution by the construction ad + accusative. For example, ad carnuficem dabo.

The accusative case developed as a prepositional case, displacing many instances of the ablative. Towards the end of the imperial period, the accusative came to be used more and more as a general oblique case.

Despite increasing case mergers, nominative and accusative forms seem to have remained distinct for much longer, since they are rarely confused in inscriptions. Even though Gaulish texts from the 7th century rarely confuse both forms, it is believed that both cases began to merge in Africa by the end of the empire, and a bit later in parts of Italy and Iberia. Nowadays, Romanian maintains a two-case system, while Old French and Old Occitan had a two-case subject-oblique system.

This Old French system was based largely on whether or not the Latin case ending contained an "s" or not, with the "s" being retained but all vowels in the ending being lost (as with veisin below). But since this meant that it was easy to confuse the singular nominative with the plural oblique, and the plural nominative with the singular oblique, along with the final "s" becoming silent, this case system ultimately collapsed as well, and French adopted one case (usually the oblique) for all purposes, leaving the Romanian the only one to survive to the present day.

Wider use of prepositions

Loss of a productive noun case system meant that the syntactic purposes it formerly served now had to be performed by prepositions and other paraphrases. These particles increased in number, and many new ones were formed by compounding old ones. The descendant Romance languages are full of grammatical particles such as Spanish donde, "where", from Latin de + unde, or French dès, "since", from de + ex, while the equivalent Spanish and Portuguese desde is de + ex + de. Spanish después and Portuguese depois, "after", represent de + ex + post.

Some of these new compounds appear in literary texts during the late empire; French dehors, Spanish de fuera and Portuguese de fora ("outside") all represent de + foris (Romanian afară – ad + foris), and we find Jerome writing stulti, nonne qui fecit, quod de foris est, etiam id, quod de intus est fecit? (Luke 11.40: "ye fools, did not he, that made which is without, make that which is within also?"). In some cases, compounds were created by combining a large number of particles, such as the Romanian adineauri ("just recently") from ad + de + in + illa + hora.

As Latin was losing its case system, prepositions started to move in to fill the void. In colloquial Latin, the preposition ad followed by the accusative was sometimes used as a substitute for the dative case.

Classical Latin:

Marcus patrī librum dat. "Marcus is giving [his] father [a/the] book."

Vulgar Latin:

*Marcos da libru a patre. "Marcus is giving [a/the] book to [his] father."

Just as in the disappearing dative case, colloquial Latin sometimes replaced the disappearing genitive case with the preposition de followed by the ablative, then eventually the accusative (oblique).

Classical Latin:

Marcus mihi librum patris dat. "Marcus is giving me [his] father's book.

Vulgar Latin:

*Marcos mi da libru de patre. "Marcus is giving me [the] book of [his] father."

Pronouns

Unlike in the nominal and adjectival inflections, pronouns kept great part of the case distinctions. However, many changes happened. For example, the /ɡ/ of ego was lost by the end of the empire, and eo appears in manuscripts from the 6th century.

Adverbs

Classical Latin had a number of different suffixes that made adverbs from adjectives: cārus, "dear", formed cārē, "dearly"; ācriter, "fiercely", from ācer; crēbrō, "often", from crēber. All of these derivational suffixes were lost in Vulgar Latin, where adverbs were invariably formed by a feminine ablative form modifying mente, which was originally the ablative of mēns, and so meant "with a ... mind". So vēlōx ("quick") instead of vēlōciter ("quickly") gave veloci mente (originally "with a quick mind", "quick-mindedly") This explains the widespread rule for forming adverbs in many Romance languages: add the suffix -ment(e) to the feminine form of the adjective. The development illustrates a textbook case of grammaticalization in which an autonomous form, the noun meaning 'mind', while still in free lexical use in e.g. Italian venire in mente 'come to mind', becomes a productive suffix for forming adverbs in Romance such as Italian chiaramente, Spanish claramente 'clearly', with both its source and its meaning opaque in that usage other than as adverb formant.

Verbs

In general, the verbal system in the Romance languages changed less from Classical Latin than did the nominal system

High Heels Off

Mary Jean Hd Sex

High Heels Shop

Elsa Jean Porno New Kino

Deepthroat Gag Video

Vulgar Latin - Wikipedia

Vulgar Latin | language | Britannica

vulgar latin - Перевод на русский - примеры английский ...

What is Vulgar Latin? — Latinitium

Vulgar Latin - Wikipedia

Вульгарная латынь - Vulgar Latin - other.wiki

Vulgar Latin - McGill University School of Computer Science

Vulgar Latin: Why Late Latin Was Called Vulgar

Appendix:Vulgar Latin Swadesh list - Wiktionary

Vulgar Latin

.jpg/300px-Sacramenta_Argentariae_(pars_brevis).jpg)

%3amax_bytes(150000)%3astrip_icc()/marble-plates-with-an-inscription-in-latin-916389698-5c397ff8c9e77c000128b95e.jpg)

/cicero-2663152-5b68b97fc9e77c0082587db3.jpg)