The Swan Knight and the Smith

Watonos

As we have seen the otherworldly island contains the source of immortality, the food or drink of the gods, which can be represented in myth as golden apples, a cauldron, or a grail. Not only does the heroic undertaking by a mortal reveal the archetype of the questing Swan Knight, but also that of a smith.

Goibniu was a smithing god in Irish mythology, and had a connection to the Ale of Immortality. His recovery from a fatal wound by the waters of the well of Sláine also links him to immortality. Goibniu, Credne, and Luchtaine, formed the Trí de Dána, “Three gods of Craftmanship”. They are similar to the Vedic Rbhus, who were three craftsmen, mentioned in the Rig Veda. Originally mortal, they were able to attain immortality through their skilled work. While Goibniu was linked to the cow of abundance, Glas Gaibhnenn, the Rbhus were also connected to a milk-cow, which they had crafted. Similarly, in Germanic myth, the legendary smith Wayland (Norse Vǫlundr) also had two brothers. Rydberg made a compelling case that these three brothers, Slagfinn, Egil, and Vǫlundr, were the same as, Idi, Gang, and Thjazi, the sons of Ivaldi. The Rbhus created the chariot of the Asvins; similarly, the Sons of Ivaldi created the ship Skidbladnir for the Norse equivalent of the Asvins, Freyr.

Read more on the comparison of Volundr to Thjazi

Vǫlundr, the protagonist in the Norse myth Völundarkvitha, took the Swan Maiden to be his wife. Thjazi on the other hand, took Idunn, who as has been made clear, occupied a similar role to that of the Swan Maiden. While Idunn is abducted by Thjazi, her Greek equivalent Hebe suffers no such fate. Instead, her replacement Ganymedes is abducted by an eagle, to serve as cupbearer for the gods. To reinforce the argument that Athena took on traits from Hebe (see part 2), that would be more fitting for the youthful maiden; the Greek smith god Hephaestus forced himself upon Athena, much like the narrative found in Wayland’s myth, where he forces himself upon Niðhad’s daughter, Böðvildr, who is likely a stand-in for the Swan Maiden he took as his consort earlier in the myth. Rydberg connects Niðhad to Mimir, as such, the king's daughter, Böðvildr, becomes a maiden connected to a well.

Read more on the comparison of Niðhad to Mimir

Read more on Mimirs association with Soma

King Niðhad had Vǫlundr imprisoned on an island, with his hamstrings cut.

As revenge, the smith killed Niðhad’s two sons, and impregnated Böðvildr. He then flew away on wings he had crafted. This is reminiscent of the skillful Greek craftsman Daedalus, who had escaped imprisonment by King Minos, with the use of crafted wings. Interestingly, an Etruscan jug seems to link Daedalus to a divine rejuvenating woman as well. Though there are no myths linking the two, Daedalus is shown, paired with Medea, who is depicted restoring life. There might also be a connection to the Greek hero Bellerophon, who was crippled after falling from the winged horse Pegasus, in his attempt to reach Olympus, to join the gods.

Like Wayland, Hephaestus was also crippled. This can be explained euhemeristically, as early bronze metalworking used arsenic, likely leading to the crippling of smiths. This might also be the reason why smiths are found in myths connected to healing waters. Hephaestus was exiled from Olympus for being crippled, and was cared for by the mother of Achilles, Thetis, herself a water nymph, forced to marry the mortal Peleus, as he clung to her while she attempted to escape by shape-shifting. Hephaestus desired to be re-admitted into the company of the gods, which falls in line with the theme of the craftsman attempting to gain access to the divine realm, which is also echoed in Vedic hymns mentioning the Rbhus, and the myths around Wayland. Hephaestus was eventually returned to Olympus by Dionysus, who is also similar to Soma.

Read more on the comparison of Dionysus to Soma

The attempted rape of Athena, by Hephaestus, produced a culture hero, Erichthonius. He is said to have introduced the yoking of horses for the use of charioteering, ploughing the earth, and the smelting of silver. He would grow up to become king of Athens, and married Praxithea, a water nymph, continuing the trend we’re observing.

We will look at the establishment of a legendary lineage through interaction with the divine maiden. The mention of a progenitor culture hero related to the sea goes back to the earliest written sources, and continued into the middle ages, as evidenced by the legend of the progenitor of house Luxembourg, Siegfried. He married the water nymph Melusine, but upon his breaking of a common Swan Maiden taboo, she disappeared into the rock upon which Siegfried’s castle stood. Interestingly, she is said to resurface once every seven years with a golden key, and will marry the one that can take it from her, which seems reminiscent of the legend of the sword in the stone commonly associated with King Arthur. Both Excalibur and Melusine are from Avalon.

There also seems to be a thematic consistency with the Swan Maiden narrative, where the water nymph has to marry the one who takes something from her. This is also continued in folktales such as The Golden Bird, in which, obtaining a feather of a bird that was stealing golden apples results in a marriage to a princess, and securement of kingship.

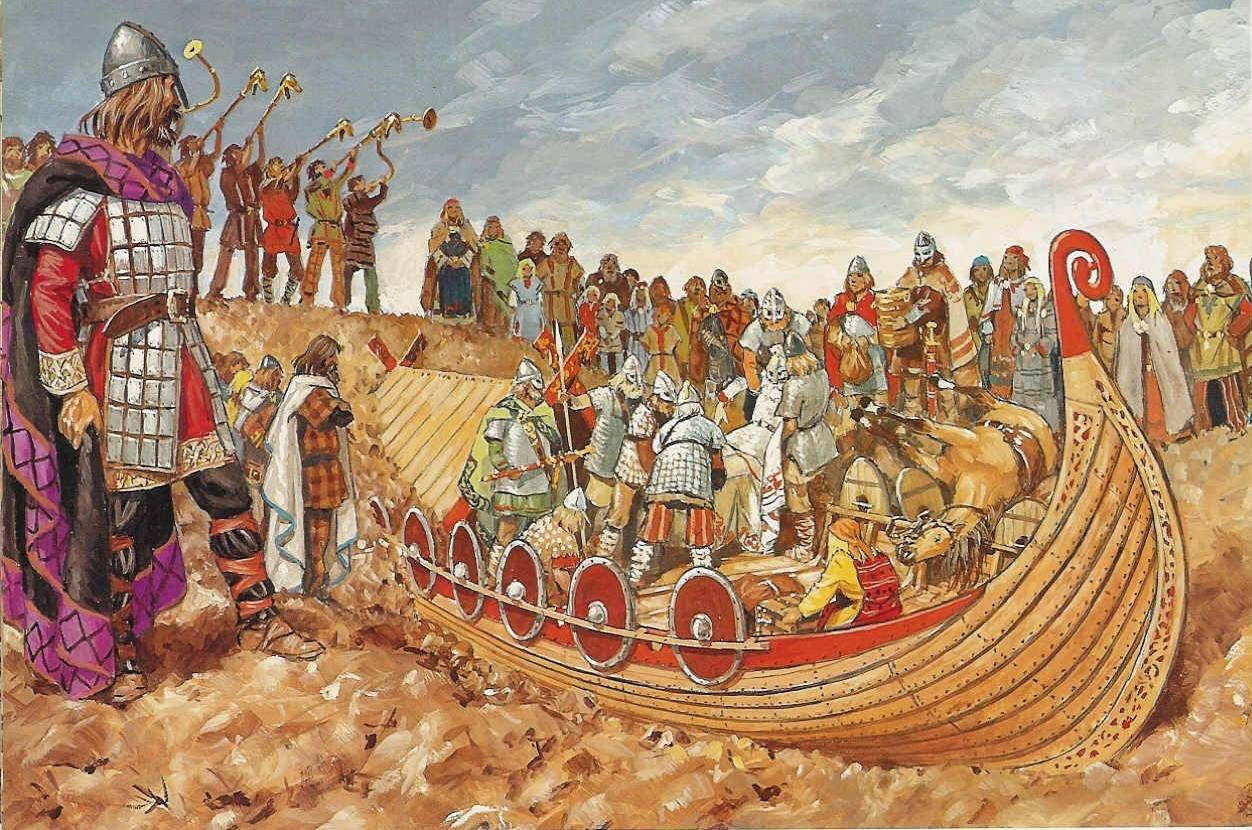

In some instances, the progenitor can be considered equivalent to the divine horse twins, such as the ancestor of the Ynglings, who is said to be descended from the Norse Freyr, who in turn is not only associated with boat burials, linking him to the sea, but he is also tied to the concept of sacral kingship. Another example would be the brothers Hengist and Horsa, “Stallion and Horse”, the first kings of the Jutes in Kent. A connection to the sea is also found in The Chronicle of Fredegar, which related the legend of the progenitor of the Merovingians, Merovech, whose mother became pregnant after an encounter with a sea creature, while bathing in the sea. This is reminiscent of Greek heroes Bellerophon, and Theseus, who likewise had double paternity, due to the intervention of sea god Poseidon. Like Freyr, Bellerophon had a strong association with horses, he was the rider of Pegasus. This winged horse was also an offspring of Poseidon, and thus could be horse twins with Bellerophon in another way. The horse twins Castor and Pollux, also have a kind of double paternity, and together with their sister, Helen, they might be thematically connected to the Swan Maiden as well. Zeus in the guise of a swan, feigned pursuit by an eagle, and either seduced or raped their mother Leda.

This Sceafa was the ancestor of the Anglo-Saxons, and arrived to the shores of Great Britain in an empty skiff coming out of the sea. Related, the progenitor of the Scyldings, was Scyld, son of Scef, his ship burial is described in Beowulf, merging his legend with that of Sceafa. In Fornmannasögur, he is even mentioned as Skjöld, Skáninga goð, god of the Scanians (Scandinavians).

Another figure that emerges in the myths of Europe is that of the Swan Knight who arrived from the Otherworldly island as a culture hero, as such he occupied the same role as the son of the hero and the water nymph. The Arthurian, Lohengrin, son of Percival, is mentioned as arriving in a swan-drawn boat, from the Grail castle, across the water, to rescue a maiden who could never ask his name. Here we see a similar taboo to those often found in Swan Maiden myths. He married her, and in the end returned to the Grail castle. The Swan Knight Helyas, Chevalier au Cigne, was noted as the legendary ancestor of Godfrey of Bouillon in the Crusade Cycle of Chansons de Geste. Helyas had arrived in a swan-drawn boat, which transported him from his island home to protect the besieged Duchess of Bouillon, afterwards they were married, gaining him the Duchy of Bouillon.

Apollo also displays some interesting characteristics. His birth took place on the island of Delos, where in that instant everything turned to gold, and the scent of ambrosia lingered in the air. Nymphs sang a holy chant of the goddess of childbirth, Eileithyia, and swans circled the island seven times. There seems to be some thematic overlap as the swans are also mentioned to have been singing. The nine Muses, companions of Apollo, were sometimes referred to water nymphs. He is of course also connected to Hyperborea, its description is very similar to other paradisaical places (described in part 2). Apollo would spend winters in Hyperborea, and when he returned, spring followed, which is similar to the beliefs in Slavic mythology, linking the migrating swans to the return of the spring. This could also help us understand Apollo’s otherwise unexplained swan-drawn chariot.

Lancelot du Lac (“Lancelot of the Lake”), while not typically considered a Swan Knight, shares the usual characteristics. He derived his name from the lake from whence he came, as mentioned in the works of Chrétien de Troyes. Ulrich von Zatzikhoven has the infant Lancelot taken by the water nymph Merfeine, known as the "Lady of the Sea", and brought to her Land of Maidens, to be raised there. A child taken by a water nymph to be raised in the Otherworld, and to later return as a culture hero, is also related in the Rig Veda, when the son of Purūravas, Ayu is taken by his mother Urvaśı. Upon this return, Ayu would become so successful, that his mention was synonymous with the Aryan forces. The Mahabharata contains another example: here, Bhishma, son of Shantanu, was taken by his mother, the river goddess Ganga. His mother told Shantanu that she would take him to the heavens to train him properly for the king's throne. Then she disappeared along with the child. Bhishma became a capable ruler, and was returned to his father as promised.

Lancelot was later found insane in the garden of the grail maiden, Elaine of Corbenic.

The Grail castle, Corbenic, which was similarly described to the Celtic Otherworld, was the Domain of the Grail keeper, also known as the Fisher King. Elaine, his daughter, brought the Holy Grail to Lancelot, and cured him of his madness. Lancelot begat a son with her, Galahad, who would grow to become the greatest knight in the world, one chosen to discover the Holy Grail. With the swan represented as a sacred bird of the Grail, it is no surprise that this narrative led to the legend of the Swan Knight.

Read more of the connection between the Fisher King and Soma

The origin of these Swan Knight tales, is intertwined with that of widespread continental folktales, such as “The Six Swans”, or “The Wild Swans”. The connection is found in Li romans de Dolopathos. It describes a lord’s encounter with a bathing Swan Maiden. She later gave birth to six boys and a girl, with golden chains about their necks, which allowed for metamorphosis into swan-form. Their step-mother ordered them killed, but the one tasked to do it, decided to hide them in the woods instead. In the end, one boy’s chain was damaged, and he had to remain as swan. The work says that this swan was “that tugged by a gold chain an armed knight in a boat”. The Irish tale The Children of Lir is very similar. Here, the jealous step-mother Aoife set out in her chariot with four children, intending to kill them. She instead had them bathe, and used magic to transform them into swans. These are considered to fall under the The Brothers Who Were Turned into Birds Aarne–Thompson type, but seem to ultimately derive from a Swan Maiden narrative. Silver or golden chains around the neck are a recurring element in these tales, also seen in Serglige Con Culainn (described in Part 1), ironically, it is these chains that seem to firmly bind these narratives together.

The story of the Swan Knight Helyas, son of King Oriant of Illefort, “Strong Isle”, has Queen Matabrune order seven children to be drowned in the river; but they were hidden away in the woods. Eventually the seven children were found sitting under a tree eating wild apples, and their silver chains were stolen, except for the one belonging to Helyas.

There is also similarity to the story from the Mahabharata, where the Kuru King Shantanu saw the beautiful woman Ganga on the river bank. She agreed to marry him, but with a condition: he would never question her actions. Eight children were born, but seven were drowned by their mother. Only the last, Bhishma, remained, due to his father’s intervention. He questioned her, and thus broke the taboo. She explained that their children were the divine Vasus, born as mortals as punishment, their deaths allowed them to return as they once were. Not only does this myth contain the usual Swan Maiden narrative, and the associated taboo, but also the theme of children to be drowned, their transformation, and one of the siblings remaining. These Vasus earned this punishment for stealing a wish-bearing cow. Interestingly, an Irish folktale mentions the theft of Goibniu’s cow, Glas Gaibhnenn. In the Mahabharata, this leads to the birth of Bhishma, through the union of a mortal with a river goddess, in the Irish tale, it leads to the birth of Lugh, son of Cian and Ethniu, an island maiden.

The sequence associated with the birth of a son, seems to be a shared characteristic of Bhishma and the Norse Heimdallr, who is described as "son of one and eight waves". Heimdallr clearly has a similar function to Bhishma, that of the classical culture hero, specifically as progenitor of the castes, as mentioned in the Rígsthula. Dumezil reached the same conclusion in Gods of the Ancient Northmen. According to him Heimdallr and Bhishma function in a similar way, having the role of a “frame hero”, later he also mentions there is a link between Heimdallr and Welsh mythology, as the water nymph Gwenhidwy’s waves were ewes, and the ninth a ram, an animal associated with the Norse god.

Apart from Heimdallr's birth, Rydberg showed in Teutonic Mythology that the Norse god drank from the three wells underneath Yggdrasil, one of which, Urdr's Well is mentioned in Gylfaginning as feeding the two progenitors of swans.

Heimdallr was born to nine sisters, likely daughters of the sea. The Arthurian Morgen was described in Vita Merlini as having eight sisters. Her name “Sea Born” indicates a connection to the Nymphs, that were usually the daughters of the sea god.

Likewise, in Norse myth, both Aegir (“Sea”) and Njordr, (a possible conflation) were said to have nine daughters, which have been considered the same as Heimdallr’s nine mothers. In the Irish Dindshenchas of Inber Ailbine, the hero Ruad, Son of Rigdonn, met nine maidens at sea, and spent nine nights under the waves, then had a child with one of them.

Nine women often appear in Arthurian legend, for example, the Welsh Preiddeu Annwfn had nine otherworldly maidens. There are also several instances in Icelandic sagas, such as Þiðranda þáttr ok Þórhalls, where Þiðrandi encounters nine women, who seem connected to the afterlife.

Unsurprisingly, Grimm states in his Teutonic Mythology that nine Valkyries usually ride out, confirmed in Saemunddredda, where one of the Valkyries mentioned having eight sisters. In the Welsh Peredur Son of Efrawg of the Mabinogion, the hero vowed to protect a countess under siege, and when confronting a sorceress, she took him back to stay a while at the palace of nine sorceresses to “learn chivalry and the use of arms”, much like Lugh was made fit for warfare and sovereignty, and Bhishma was trained for the throne. This is not far off from the heroic Arthurian king himself, Arthur, who recovers in the Otherworld, set to return one day.

Nine druidesses are mentioned by Pomponius Mela in Description of the Earth, they were called the Gallisenae; and lived on the island of Sein. Like the other maidens, they are capable of shapeshifting, extraordinary healing, and foreknowledge. They are also able to control the winds and the seas, which seems fitting, as most of the maidens we have looked at are closely connected to the sea.

Nine korrigans, which could be fairies, are mentioned in the Breton poem "Ar rannoù”. They are said to dance around a spring by the light of the full moon, in clothes of white wool. The often recurring mention of the moon in tales of such maidens can be explained by their close association to the source of immortality, continuing the theme found in the Vedas, where Soma is conflated with the Moon.

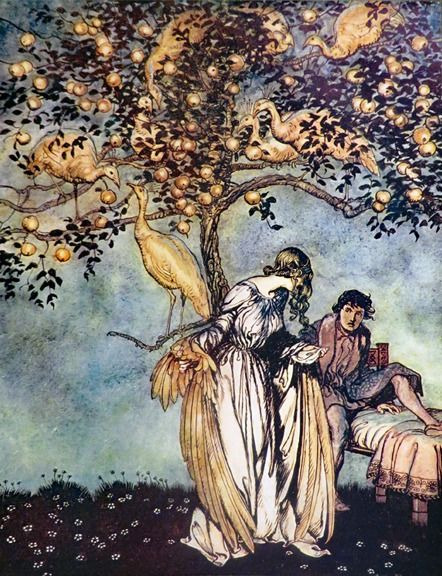

The Serbian epic poem The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples, the Russian folktale Tsarevitch Ivan, the Firebird and the Gray Wolf, the German The Golden Bird, and the Romanian Prâslea the Brave and the Golden Apples, all contain the narrative of a garden filled with golden apples, and their theft. Though here, the heroic journey is not undertaken to obtain the apples, but to seize the perpetrator, or otherwise halt further theft.

The abduction of the Dawn goddess, or the forcible removal of the Swan Maiden from the divine realm, one who is linked to the source of immortality, can be seen as comparative to the theft of Soma. As such, the abduction of Helen might be a version of this tradition. The theft of Soma can also be considered similar to Prometheus’ theft of fire. It is however the myth of Tantalus that is the most similar. He was welcomed on Olympus, but attempted to steal ambrosia and nectar, and was punished for it, for eternity. Prometheus as culture hero, not only gifted fire to man, but also introduced animal sacrifice. Similarly, Soma, after it was stolen, was obtained by Manu, the first sacrificer. In Theogony, Hephaestus had to create the first woman, because Prometheus’ theft of fire. This is somewhat of a reversal of the narrative in the Śatapatha Brahmana, where Pururavas gains fire to sacrifice with, after being left by the Apsara Urvasi.

In The Swan-Maiden Revisited, Miller concludes that the narrative can be traced back to shamanistic origins, with supporting archeological evidence found in Siberia. Also the Saami considered swans as messengers of the gods, also the Bronze Age Vedbæk grave of the Ertebolle Culture from Denmark, revealed a child was laid upon the wing of a swan, which might be the oldest indication of the significance of the swan in relation to the afterlife.

Pururavas no longer connected to the immortal Apsara, was now bound to death, but his son Ayu was returned to him, allowing his lineage to continue. The last words in the hymn by Urvasi are hopeful: “Your progeny will sacrifice to the gods with an oblation, but you will also rejoice in heaven”

It is noteworthy that this is the only time svargá (“heaven”) is found in the Rig Veda.

We can conclude that the abduction of the Swan Maiden could be seen as a way for the mortal to establish a connection to the divine, on his terms. But if anything can be considered hubris, it is the quest for equal footing with the gods, and if it is undeserved, it will be punished, as seen in the myths of Bellephoron, Wayland, Prometheus, and Tantalus.

Vǫlundr did not pursue his Swan Maiden wife, but crafted a ring of gold, so that he would be worthy, and she would return. This is similar to the Rbhus gaining access to the sacrifice through their craftsmanship. In their own way, they are unmatched in skill, and as such, earn the respect of the gods.

The Swan Maiden myth, finally, does not reduce the divine woman, nor elevate the mortal man, through their interaction. It instead initiates the struggle to break free from death, the desire for immortality, or divinity. Ultimately, this quest leads onwards and upwards, Heracles being the paragon of this heroic endeavor, while the Swan Knight’s boat guided by the swan conveys the divine guidance needed for such heroism. The Roman equivalent to Hebe, Juventas, was as such regarded as “a powerful divine force rendering a vital gift of strength at a critical moment”.

Another aspect that we should consider is the propensity to place the islands within reach, this is shared throughout the various traditions. In a way this relates that the Otherworld is attainable. The aforementioned Gallisenea would grant their favors only to those who come to their island on purpose to consult them. Like most of these myths, they have imbedded within them a call to heroic action, or the perfection of skill. To achieve immortality, to gain the favor of the gods, you have to get out there and achieve greatness.