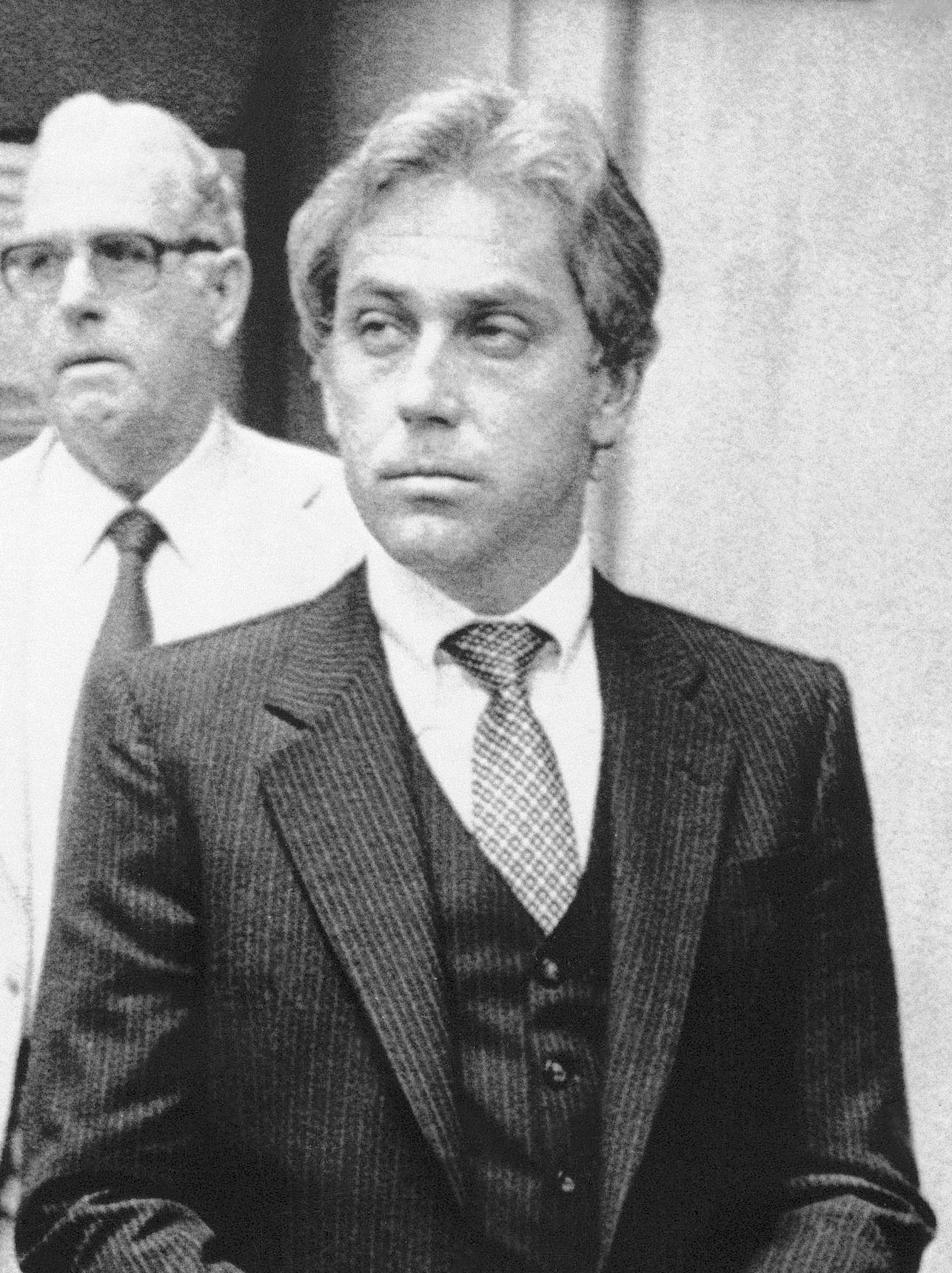

The Story Of Family Annihilator - Jeffrey Robert MacDonald

@crimestoryy on telegram

Jeffrey Robert MacDonald is an American family annihilator who, on August 29, 1979, was convicted of the 1970 murders of his wife and two daughters. He repeatedly appealed the conviction and currently proclaims his innocence.

Background

MacDonald was born on October 12, 1943 in Jamaica, Queens (New York) and raised in a poor neighborhood on Long Island. His father was highly disciplinary, but not abusive. In high school, MacDonald was highly popular and was the student council president. It was in 8th grade that he met his future wife (and later victim) Colette Stevenson. The two dated until 9th grade, when Stevenson ended their relationship. The two eventually rekindled their relationship while they were both in two separate colleges. They eventually married on September 14, 1963 after finding out that she was pregnant. The MacDonalds had two daughters together.

MacDonald and his family moved to Fort Benning, Georgia after he enlisted in the U.S. Army as a physician in 1969 and rose to the rank of captain in 1970. The family lived on the base in a special quarters and became known among its other inhabitants. Stevenson also became pregnant with the couple's third child around this time. The MacDonalds were known to argue occasionally, but were mostly considered good people by those who knew them.

Fort Bragg Murders

In the early morning hours of February 17, 1970, MacDonald called the military police reporting that there had been a stabbing at his home. The arriving officers entered through the back and found MacDonald and his wife in the bedroom, the former badly wounded and the latter brutally murdered. The children were also found dead upstairs in their bedrooms. MacDonald was hospitalized and treated for injuries similar to his wife and daughters' (though his were far less severe) and, after his release, was questioned by the CID. MacDonald alleged that three men had broken into the home and attacked him and his family, knocking him unconscious and, after he awoke, tried in vain to resuscitate his wife and daughters.

Further investigations found that, in addition to no evidence of the alleged perpetrators of the massacre (who MacDonald alleged consisted of two Caucasian males, one African-American male, and a Caucasian woman who he thought could have possibly been a man disguised as such), but also found several suspicious items that seemed to have been the weapons used in the massacre that were wiped of fingerprints. Further extensive forensics investigations also came up with numerous findings and additional evidence that greatly contradicted MacDonald's version of what happened. MacDonald himself could provide little evidence supporting his claims and even refused a polygraph test (despite initially agreeing to submit to one). MacDonald was charged with murder on May 1, 1970.

First trial

MacDonald was represented by defense attorney Bernard Segal, who alleged that forensic investigators had over-looked or even destroyed evidence supporting his client's story and even helped identify a potential suspect named Helena Stoeckley (a teenage drug-addict and police informant who also fit the description of the blonde woman MacDonald alleged had been at the scene). Stoeckley had been seen by a witness with several young men, though she was unable to recount what she had done on the night of the murders. She also supposedly told the witness that she could not marry her boyfriend until they killed someone. Although Stoeckley and her boyfriend were both questioned about the murders, they were ultimately never brought to trial and, as evidence was insufficient, the charges against MacDonald were dropped in October 1970.

Second trial, conviction, appeals

MacDonald was discharged from the Army and relocated to California and held down several medical professions, primarily as a physician. He received great media attention and granted numerous interviews and even appeared on TV.

in 1971, Stevenson's stepfather, Alfred Kassab (who had originally supported his stepson in-law during the initial trial) became increasingly suspicious of him. MacDonald had refused to give him a transcript of the Article 32 hearing, displayed a very casual demeanor in his TV interview, and even alleged that he and some Army collogues had actually tracked down and murdered one of the alleged perpetrators of the murders. Kassab began his own investigation of MacDonald, obtaining the desired transcript and found many inconsistent details in it. He even re-visited the original crime scene to compare evidence and became convinced that MacDonald was in-fact the true killer. He tried for some time to bring MacDonald to trial (something that could only be done by filing a citizen's complaint filed through the United States Department of Justice) but without success. The Kassab family, their attorney, and a CIP agent presented a citizen's complaint against MacDonald to US Chief District Court Judge Algernon Butler, requesting the convening of a grand jury to indict MacDonald for the murders on April 30, 1974; it was granted a month later and, eventually, MacDonald was brought to trial for a second time on July 16, 1979.

Much like in the first trial, forensic evidence contradicted MacDonald's claims of what happened. Stoeckley was questioned extensively by Segal, but she ultimately alleged she could not recall her whereabouts at the time of the murders and her testimony was never introduced. MacDonald finally testified for himself and, much like before, was unable to provide an explanation for the many discrepancies in his story. After an extensive trial, MacDonald was convicted of one count of first-degree murder and two counts of second-degree murder on August 29, 1979 and received three life sentences. Several months before his conviction, MacDonald invited author Joe McGinniss to write a book about his case, hoping it would shed further light on his innocence. The book, Fatal Invision, instead further portrayed MacDonald as guilty, resulting in him suing McGinniss for fraud several years after his conviction. The case was settled out of court with MacDonald receiving only $50,000 of $325,000 (the remaining $275,000 was awarded to the Kassabs after they filed their own countersuit against him for an inheritance clause).

MacDonald has since filed several appeals to his sentence and, despite being temporarily freed on bond, currently remains incarcerated at Cumberland Federal Correctional Institution in Cumberland, Maryland, where he continues to maintain his innocence to this day. He also married former children's drama school owner/operator named Kathryn Kurichh while in prison in August 2002 and unsuccessfully tried for parole several times.

Modus Operandi

MacDonald employed at least four weapons, leaving aside his own fists, during the course of his murderous rampage:

A piece of lumber, which he used to club his wife, breaking her arms, and with which his older daughter, Kimberley, was either unintentionally or intentionally hit.

A Geneva Forge paring knife, which he used to stab his wife.

An Old Hickory paring knife, which he used to stab both his wife and daughters.

An ice pick, which he used to stab both his wife and younger daughter.

He also staged the scene to appear as if a Manson Family-like group invaded his house, murdered his family, and wounded him. He inspired himself to articles he read on Esquire, and, wearing surgical gloves, used Colette's blood to write the word "pig" on their bed's headboard. Finally, he non-lethally stabbed himself with a scalpel, called an ambulance, and discarded the weapons and gloves.

Profile

MacDonald was evaluated by a psychologist, who concluded that he had an extraordinary absence of anxiety, depression, and anger in regard to the death of his family, and that his report concluded he was "able to muster massive denial or repression" to such a degree that the "impact of the recent events in his life has been blunted". Bruce Bailey (a psychologist from MacDonald's original trial) noted that MacDonald was able to recover quickly from being distressed and testified he found MacDonald to be a controlling individual who was "extremely dependent on what others thought of him" and that he would often launch into a verbal "tirade" to allow his deep-seated emotions to become expressed by other means. When questioned as to whether MacDonald suffered from a mental disorder, Bailey testified he did not, although he could not discount the possibility of him murdering members of his family in a situation of extreme stress. This testimony was followed by a Philadelphia-based psychologist who conceded that, had MacDonald committed such an act of violence, he would successfully "completely block" the episode from his mind.

A report by psychologist Hirsch Silverman (which was quoted by McGinniss) stated that MacDonald "handled his conflicts by denying that they even exist", adding that MacDonald lacked any sense of guilt, had been capable of committing "asocial acts with impunity", and had been "incapable of [forming] emotionally close" relationships with females of any age. Silverman further states MacDonald had avoided and resented his commitments as a husband and father and that, given his ongoing "denial of truth", he would continually seek both attention and approval.

He was also known to have behaved arrogantly and sarcastically during his testimony and was also both surprised and frustrated at the investigator's thoroughness. MacDonald was portrayed as a "narcissistic sociopath" by the novel Fatal Vision.

Known Victims

February 17, 1970: 544 Castle Drive, Fort Bragg, North Carolina:

Colette MacDonald, 25 (his wife; beaten and repeatedly clubbed with a piece of wood, both her arms were broken; later stabbed 21 times with an ice pick, and 16 times with a knife; was pregnant)

Kimberley MacDonald, 5 (his older daughter; clubbed in the head with a piece of wood; stabbed in the neck between 8 and 10 times with a knife)

Kristen MacDonald, 2 (his younger daughter; stabbed 33 times with a knife, and 15 times with an ice pick)

@crimestoryy on telegram