The Shirt Stays On

@americanwords

“Aren’t you going to take your clothes off?” she asked, her fingers pulling at the edges of my T-shirt. It wasn’t sexy the way she said it; no wry smile or soft coo came with the words, just frustration.

The ceiling lights were off, but I knew the narrow light spilling from the lamp on my bureau would be enough for her to see the pale red marks on my chest, which had been fading for so long they had gone back to being shiny again.

No one had ever put that question to me so directly. When it came to keeping my shirt on, I had always gotten away with playing dumb or chalking it up to the hastiness of passion.

“I have scars,” I managed to say, as bluntly as I could.

I was born with a rare heart defect for which there is no cure, only a series of stopgaps and half-measures. I had undergone four full open-heart operations by age 15, as well as dozens of less invasive procedures, and am on my fourth pacemaker.

Now 23, I’ve spent nearly 20,000 hours of my young life inside hospital walls. For many years, I was not healthy enough to live out of the hospital for more than a few weeks at a time.

These surgeries have left many scars. One cuts across my right clavicle on a diagonal, the entry for my second pacemaker at age 12, after the battery for my first died so abruptly that my mother received a voice mail message while in the car that said: “You need to come in. Jameson’s device is in end-of-life mode.”

Two more scars run horizontally across my midsection. The one on the left was carved so recklessly that it created a pocket with a pouch of skin above. Then there is the main attraction: a footlong line that stretches from between my clavicles to just a few inches above my bellybutton.

This one has been carved up so many times by surgical tools rolling over it again and again, like a pizza cutter, that different sections have taken on different colors, textures and thicknesses.

The bottom part is bright red, bumpy and ugly. The top third is a straighter line and, having not been disturbed in years, paler than the rest. Before long I’ll be able to wear a V-neck without it being spotted.

But this wasn’t all. There were the stretch marks, too, caused by the way my abdomen ballooned with undigested liquids (a kind of beer belly driven by heart failure) that were emptied each day via diuretics and regular fluid taps.

And there was the divot just above my right hip, a black cavern the size of my finger from when I had a tube to empty my stomach of waste.

“This will close up in about a month,” the nurse said the day it was removed. It didn’t. “It might take a few months.” Still nothing. “It will close by itself eventually.” It never did.

When unattached and left to its natural self, the tube hung down to my waistline and pulled painfully on the skin from where it came, so every morning I packaged it up in an elaborate construction of gauze and tape to keep it secured to my skin.

I had the tube during my freshman year of college when I met the first girl I ever kissed, who then became the first girl I ever hooked up with on a consistent basis — but never without the shirt.

My first kiss was a dare. I was sitting with friends on the carpeted floor of a dorm room. We had been drinking beer and Smirnoff Ice, and my head was swirling. My weak liver and broken heart couldn’t process and redistribute blood and body fluid correctly, meaning they sure as hell couldn’t process alcohol efficiently.

I barely blinked when someone in the room suggested a game of Truth or Dare, knowing that when my turn came I would pick truth, as always. But it never got to that. Becky chose a girl, and that girl chose dare. And soon Becky’s finger was scanning the room like radar, commanding, “I dare you to kiss — —”

Her movement slowed, lingering on people as her finger passed.

The girl winced as Becky’s finger finally stopped on me, and then she shrugged.

I said nothing, planted against the dresser behind me. I thought about mentioning that this kiss, at age 18, would be my first, but I knew announcing that would be worse than just letting it happen.

She crawled over and fell forward, almost starting the kiss before she even landed. Her lips closed around mine like parentheses, touching but not connecting.

We would spend the next few weeks convening in stairwells, hiding under covers, sneaking around and keeping our secret from friends — all while rarely talking, mostly touching, never connecting.

When it ended (both of us sitting on the lip of the fountain in Washington Square Park, staring straight ahead), I wouldn’t admit to myself that the feeling in the pit of my stomach was one of relief. Relief that it didn’t get far enough to have to show her everything. She saw about 10 percent, and that was plenty. She never saw the scars. And she knew even less about what they meant.

It has taken time, nearly all of my 23 years, for me to learn how much to say, whom to tell, what to show of myself. I have learned exactly how much people care to know and what they care to know and how much it matters to them.

Whenever I first tell people about my diagnosis, I usually get a flurry of questions and then they catch themselves and say: “I hope you don’t mind me asking questions. We don’t have to talk about it if you don’t want to.”

“That’s O.K.,” I say. We’ll talk about it until you don’t want to.

It’s not that people lose interest; there just always comes a point when we need to move on and talk normally about normal things so the balance of our conversation can even out.

But something about my scars feels more precious. Almost all through childhood I carried a bit of extra weight, mostly in my stomach, and every year when summer rolled around I’d find ways to keep my shirt on in the hot sun at the beach or the pool or on vacation or at parties.

I told my parents it was because of the scars (because I was actually embarrassed by the weight), and then later told them it was because of the weight (because I was actually embarrassed by the scars).

The thing about the physical side is that I can talk all I want about what I’ve been through, what it felt like to grow up with chronic illness and to know nothing else — with the science and the diagnoses and the dates and everything that can be measured.

But the faded cuts and holes and lines that speckle my body are the closest I can get to proof. Eventually, scars will fade. But you can’t uncut skin.

And I’ve earned them. So maybe a part of me believes that seeing them is something you need to earn. I’ll show you when I know they’ll matter to you. I’ll show you when I want you to see all my scars, both above and below the surface.

I have never been in love. I have been in like. I have loved people, but I’ve never been in mutual love. I have never even been in a relationship, never called someone mine and had them call me theirs.

I’ve never found someone who cares enough to hold my hand in waiting rooms or to hear about the worst parts of everything, about all the firsts I never got to experience, or what I remembered of flatlining.

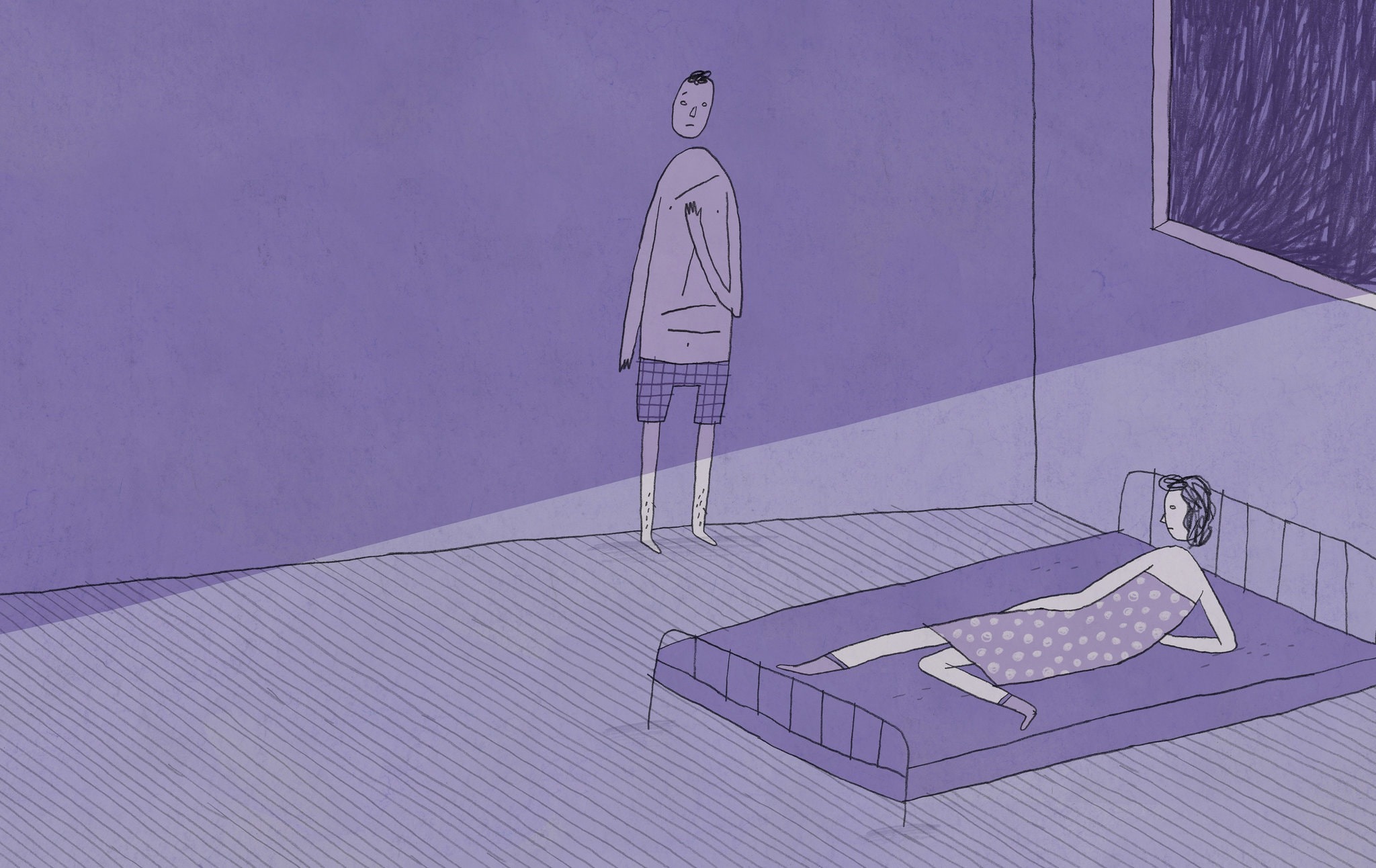

But like many people in their 20s, I have found myself in beds wrapped around people I don’t know very well, sharing our bodies before we have shared much else. So while I’m still figuring it all out, I sometimes have to improvise.

Like with the girl who acted frustrated about my not taking off my shirt. I met her on Tinder. She was in the city for only a month, visiting New York on break from college. We talked for a few days online before meeting for drinks and ultimately ending up back at my apartment.

After making out for 20 minutes, she pulled away and looked up at me in the dim light coming from the corner of my bedroom. And that’s when she said it: “Aren’t you going to take your clothes off?”

I knew she would be able to see more than I was ready to show. “I have scars.”

She just blinked.

“So?”