The Private Science of Louis Pasteur

Corona Investigative

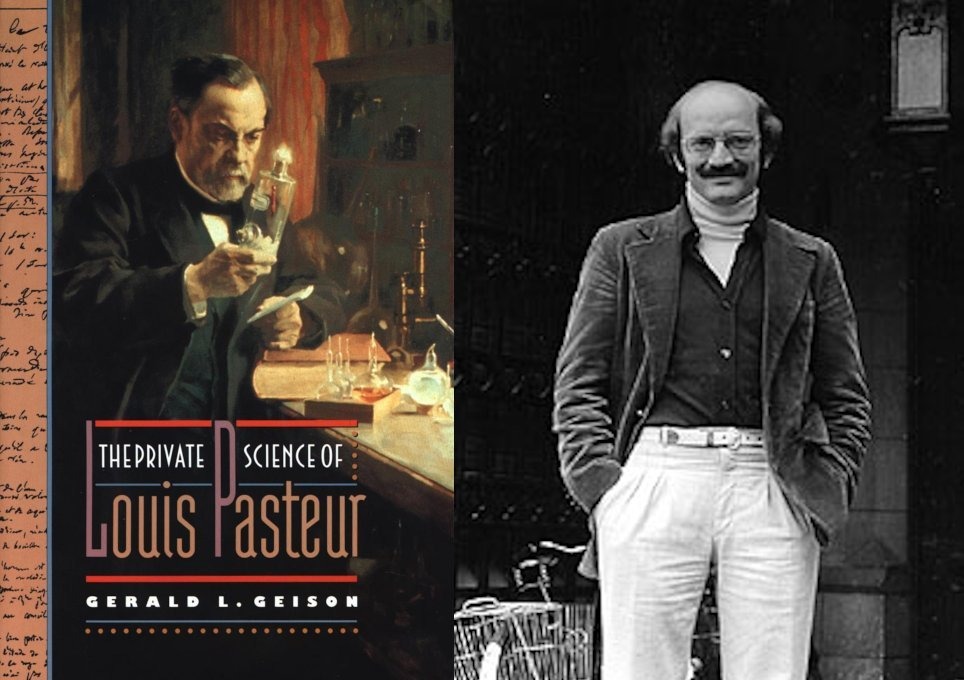

THE PRIVATE SCIENCE OF LOUIS PASTEUR By Gerald L. Geison. Illustrated. 378 pp. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

LOUIS PASTEUR embodies a most rare image, the scientist as hero. We have been told often not only of the brilliance and originality of his research, but also of its enormous practical benefits, like his cure for rabies. When he died in 1895, his funeral was designated a national event and the French state paid the bill. Raymond Poincare, a future president, proclaimed: "Adieu, dear and illustrious master! Science, which you have so grandly served -- sovereign and immortal science, become more sovereign still through you -- will transmit to the most distant ages the indelible imprint of your genius."

These days such public sentiments about science are almost inconceivable. The atomic bomb, eugenics and fraud have all helped to dim the luster of science. Scientists are portrayed more as manipulators than as heroes.

In "The Private Science of Louis Pasteur," Gerald L. Geison, a historian at Princeton University, has explored 100 of Pasteur's laboratory notebooks, now held in the National Library in Paris, which record 40 years of scientific activity and which were made available to researchers only about 20 years ago. Mr. Geison specifically disclaims any intention to deny Pasteur's greatness as a scientist, but to illuminate the scientific process, he sets out to expose some serious discrepancies between what Pasteur published and said in public and what is recorded in the notebooks.

Even with the notebooks as his guide, Mr. Geison is unable to provide a satisfactory explanation of how Pasteur made his first great discovery, in a study of isomers -- different chemical compounds that have exactly the same chemical formula. Chemists thought they could always be distinguished through other physical properties, but in 1844 two isomers, forms of tartaric acid, were found not only to have the same chemical formula but to be identical even in "the nature, number, arrangement and distances" of their atoms. Chemistry, as a science, was in trouble. Then, in 1848, Pasteur demonstrated that when these acids are crystallized, their crystals' faces are mirror images of one another and thus rotate polarized light in opposite directions. His demonstration of this structural difference, and his method of doing it, have borne abundant fruit in many branches of modern science. But his procedures in this experiment puzzle Mr. Geison, who talks of scientists constructing reality, not just interpreting facts. Well, that is at the heart of scientific creativity: Pasteur's discovery depended on exceptional skills as an observer, experimentalist and theoretician.

On the question of spontaneous generation -- can nonliving matter spontaneously organize itself into living matter? -- Pasteur claimed the issue could be decided on facts alone. However, as Mr. Geison persuasively explains, he never did believe in spontaneous generation, and when his own experiments gave the wrong result he always resorted to an alternative explanation.

When we come to anthrax and rabies, the notebooks rewrite history. In 1881, Pasteur staged a public trial of an anthrax vaccine for sheep. He was triumphant, the more so since the vaccine was not well researched, as he admitted. His public description of the vaccine implied that it was prepared by his general method of using oxygen to attenuate the virulence of the anthrax bacillus, thus making it suitable for vaccine. In fact, the method he used was similar to that of a competitor. He was deceptive because he wanted both priority and recognition. He needed both -- to find support for his work, and for personal gratification. As it turned out, his oxygen method later proved very successful.

His fascination with rabies, and with attempts to find a vaccine, was natural. As a child in the Jura Mountains, he had heard victims of attacks by rabid wolves screaming in agony as their wounds were cauterized with a red-hot iron. Proving a vaccine presented a problem: as he himself said, experimenting with animals was allowed, doing it with people was a crime. He was not medically trained. Nevertheless, in 1885 he used his vaccine in complete secrecy on two patients with rabies: a man who recovered and a child who died. In both cases doctors made the injections. The only records of these events are in the notebooks and correspondence. There is no question he was experimenting on humans, even before he had any success in curing the disease in animals.

Next a boy bitten by a rabid dog was brought to him; a doctor said the boy, Joseph Meister, faced certain death. Pasteur treated him, and he survived. Three months later he treated another victim, who also lived. He then announced that he had discovered a treatment for rabies in humans, based on experiments on dogs, and forestalled ethical criticisms by claiming that in his experiments he had "rendered a large number of dogs refractory after they had been bitten."

Pasteur lied. As the notebooks show, only some 30 dogs had been studied, and a third of them had succumbed to rabies. Worse still, not one of them was treated by the method used on Meister. The question of just what made Pasteur choose the particular treatment is quite complex, but it involved a change of mind about how immunity to rabies developed. The notebooks do not reveal his thinking. Mr. Geison speaks of "a remarkable flexibility of mind in the now aging Pasteur." But the treatment worked, and over the next 10 years some 20,000 people were treated by Pasteur's method.

Pasteur is not attractive: aloof, gruff, authoritarian, secretive, competitive, a ruthless opponent. That, from the point of view of his science, is irrelevant. His misconduct about anthrax and rabies is much more reprehensible, though as regards rabies, perhaps he could defend himself in terms of the terrible problem of coming face to face with a dying child he thought he could help.

THIS book provides a fascinating and detailed account of much of Pasteur's life and of French science in the last century. But its aim is wider. Mr. Geison thinks the episodes he examines have a contemporary message: Science, like any other form of culture, relies on rhetoric; objective, value-free science may be a myth. In fact, no matter how brilliant a scientist's rhetoric, in the long run the truth will out. Social factors influence the course of science; the outcome is determined by nature.

What this life of Pasteur shows is how complex, hard and imaginative scientific discovery is, and that it requires a variety of skills rarely found in one person. Mr. Geison has gone some way to deconstruct the myth of Pasteur and the belief that all of his science is pure and beautiful, but most of Pasteur's beautiful science still shines brightly. Dishonesty is the antithesis of the scientific endeavor; yet we can be grateful to Pasteur in spite of his misdemeanors.

(A version of this article appears in print on May 7, 1995, Section 7, Page 35 of the National edition with the headline: Experiments in Deceit)

Awards and Recognition

- Winner of the 1996 William H. Welch Medal, American Association for the History of Medicine

- One of Choice's Outstanding Academic Titles for 1995

The book in pdf format can be downloaded from here: → LINK

Telegraph main page with overview of all articles: Link

Visit our Telegram Channel for additional news & information: Link

Chat with like-minded in our Telegram Chat Group: Link

Please support to keep this blog alive: paypal