The Lhammas I

@TheSilmarillion

There are three versions of this work, all good clear manuscripts, and I think that all three were closely associated in time. I shall call the first Lhammas A, and the second, developed directly from it, Lhammas B; the third is distinct and very much shorter, and bears the title Lammasethen. Lhammas A has now no title-page, but it seems likely that a rejected title-page on the reverse of that of B in fact belonged to it. This reads:

The title-page of Lhammas B reads:

At the head of the page is written: 3. Silmarillion . At this stage the Lhammas, together with the Annals, was to be a part of 'The Silmarillion' in a larger sense.

The second version relates to the first in a characteristic way; closely based on the first, but with a great many small shifts of wording and some rearrangements, and various more or less important alterations of substance. In fact, much of Lhammas B is too close to A to justify the space required to give both, and in any case the essentials of the linguistic history are scarcely modified in the second version; I therefore give Lhammas B only, but interesting points of divergence are noticed in the commentary. The separate Lammasethen version is also given in full.

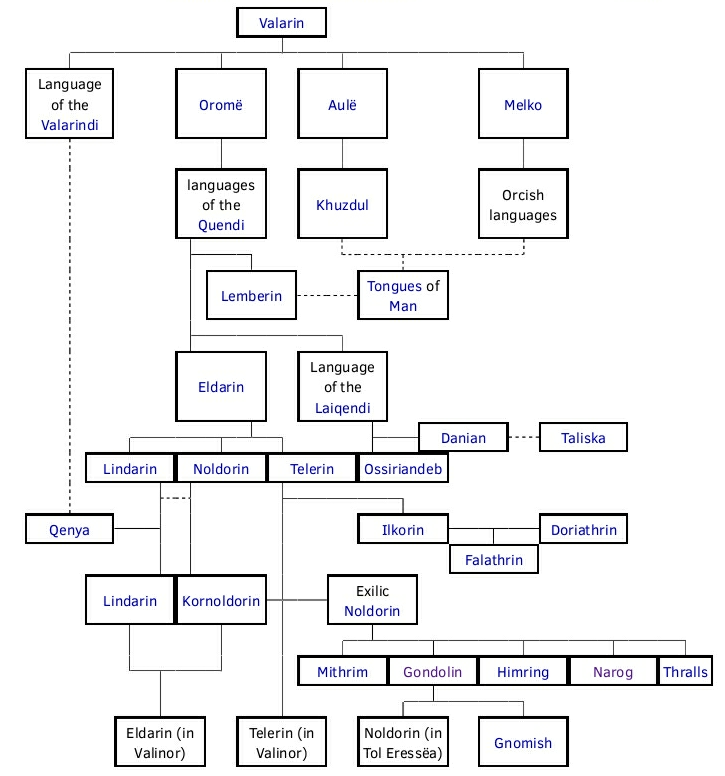

Associated with the text of Lhammas A and B respectively are two 'genealogical' tables, The Tree of Tongues, both of which are reproduced here <the only found version is included there - admin of @TheSilmarillion>. The later form of the Tree will be found to agree in almost all particulars with the text printed; differing features in the earlier form are discussed in the commentary.

Various references are made in the text to 'the Quenta'. In 5 the reference is associated with the name Kalakilya (the Pass of Light), and this name occurs in QS but not in Q. Similarly in 6 'It is elsewhere told how Sindo brother of Elwe, lord of the Teleri, strayed from his kindred': the story of Thingol's disappearance and enchantment by Melian has of course been told elsewhere, but in Q he is not named Sindo, whereas in QS he is. It seems therefore that these references to the Quenta are to QS rather than to Q, though they do not demonstrate that my father had reached these passages in the actual writing of QS when he was composing the Lhammas; but that question is not important, since the new names themselves had already arisen, and therefore associate the Lhammas with the new version of 'The Silmarillion'.

There follows now the text of Lhammas B. The manuscript was remarkably little emended subsequently. Such few changes as were made are introduced into the body of the text but shown as such.

From the beginning the Valar had speech, and after they came into the world they wrought their tongue for the naming and glorifying of all things therein. In after ages at their appointed time the Qendi (who are the Elves) awoke beside Kuivienen, the Waters of Awakening, under the stars in the midst of Middle-earth.

There they were found by Orome, Lord of Forests, and of him they learned after their capacity the speech of the Valar; and all the tongues that have been derived thence may be called Oromian or Quendian. The speech of the Valar changes little, for the Valar do not die; and before the Sun and Moon it altered not from age to age in Valinor. But when the Elves learned it, they changed it from the first in the learning, and softened its sounds, and they added many words to it of their own liking and devices even from the beginning. For the Elves love the making of words, and this has ever been the chief cause of the change and variety of their tongues.

Now already in their first dwellings the Elves were divided into three kindreds, whose names are now in Valinorian form: the Lindar (the fair), the Noldor (the wise), and the Teleri (the last, for these were the latest to awake). The Lindar dwelt most westerly; and the Noldor were the most numerous; and the Teleri who dwelt most easterly were scattered in the woods, for even from their awakening they were wanderers and lovers of freedom. When Orome led forth the hosts of the Elves on their march westward, some remained behind and desired not to go, or heard not the call to Valinor. These are named the Lembi, those that lingered, and most were of Telerian race. But those that followed Orome are called the Eldar, those that departed. [This sentence struck out and carefully emended to read: But Orome named the Elves Eldar or 'star-folk', and this name was after borne by all that followed him, both the Avari (or 'departing') who forsook Middle-earth, and those who in the end remained behind (changed from who in the end remained in Beleriand, the Ilkorindi of Doriath and the Falas).] But not all of the Eldar came to Valinor or to the city of the Elves in the land of the Gods upon the hill of Kor. For beside the Lembi, that came never into the West of the Hither Lands until ages after, there were the folk of the Teleri that remained in Beleriand as is told hereafter, and the folk of the Noldor that strayed upon the march and came also later into the east of Beleriand. These are the Ilkorindi that are accounted among the Eldar, but came not beyond the Great Seas to Kor while still the Two Trees bloomed. Thus came the first sundering of the tongues of the Elves, into Eldarin and Lemberin; for the Eldar and Lembi did not meet again for many ages, nor until their languages were wholly estranged.