The Celtic Gods of the Iberian Peninsula : Part 4 - Lucubo

Matamoro

Lucubo - Lug - Lugh - Lugus

Etymology

The exact etymology of Lugus is unknown and disputed. The proto-celtic root of the name, *lug-, is generally considered to be derived from one of the following proto-indo-uropean roots, such as *leug- "black", *leuǵ- "to break", and *leugʰ- "to swear an oath". It was once thought that the root could be derived from the proto-indo-european *-leuk- "to shine", but this etymology posed difficulties and few modern researchers accepted it as possible (in particular because the proto-indo-european *-k- never produced the proto-celtic *-g-).

Nevertheless, following the work of Françoise Bader, according to whom the indo-european root of "light" would be *-leu- and not *-leuk-, this etymology is once again considered the most convincing by specialists for whom Lugus would mean "the luminous".

Toponyms and Ethnonyms

By the yardstick of the cult dedicated to him, Lugus seems linked to prosperity, trade and crafts. His figure is associated with the spear. He is one of the most common Gods among the Celts and as we will see, a very consequent number of place names derive from Lugus throughout Europe.

The name of Lugus is consecrated in many place names, such as Lugdunum, from the Celtic *Lug[u]dūnon, which means "fort of Lugus", nowadays Lyon in France. This city was the capital of the Roman province of Gallia Lugdunensis. Other place names in which the name Lugus is found include Lugdunum Clavatum, now Laon in France, and Luguvalium, now Carlisle in England. It is also possible that Lucus Augusti, the ancient name of Lugo in Galicia, a region in northern Spain, is derived from the name Lugus, although it may also be purely derived from the Latin Lucus - "grove/sacred forest".

As for the Iberian Peninsula in particular, the presence of this deity is exacerbated by the existence of related tribes, such as the Luggones Astur, whose name probably derives from Lugus and who inhabited the city of Lugones in Asturias. There are also the Gallaecia Lougei, which we know from inscriptions found in Lugo in Galicia and El Bierzo in León .

On the other hand, we do not know to this day any denomination of this kind, therefore linked to human groups, for Bandua, Cosus or Reue, despite the large number of known inscriptions that show epithets referring to these Gods. The only appellations accompanied by their indigenous theonyms that are known north of the Duero River are allusive appellations of Lug, such as Lucubo Arquienob(o), referring to Arquius, an omnipresent cognomen in Hispania, and Tabaliaeno, which can be interpreted as another dedication to the God Lugus.

Lug thus presents close similarities with Arentius. This has often led him to be confused with the Divine Twins, as some of their features are juxtaposed with his own. Lug appears in various places in the Celtic world, but although his cult is very widespread, the low proportion of votive offerings known for this deity could lead us to underestimate his value. Fortunately, other clues allow us to re-establish that Lugus was considered one of the most important Gods of the Celtic pantheon.

As a first clue, we have to consider the many toponyms with the term lucu-, lugu-, loucu- or lougu-, linked to the name of God and found throughout Western Europe. In Hispania toponyms deriving from this theonym are known: Lucus Augsti (Lugo), Lucus (Lugo de Llanera), the ciuitas Lougeiorum, Louciocelum, Lucocadia, Lugones (Siero, probably derived from the ancient Luggoni), Logobre, Lugas...

Here is an anthology of places outside Spain bearing his name: first Loudun and Montluçon in France, Loudoun and Lothian in Scotland and Dinlleu in Wales. It is also found in the Netherlands with the city of Leiden, in Silesia with Legnica and finally in England with Luton.

Finally, there are many anthroponymes linked to the theonym Lugus: Lugaunus, Lugenicus (Born of or conceived of Lugus), Lugetus, Lugidamus, Lugiola, Lugissius, Lugius or Luguselva (chosen from Lugus). The ancestry is even clearer with these anthroponymes derived directly from the name of the deity, such as Lougeius, Lougo, Lougus, Lucus, Lugua and Luguadicius.

Iconography

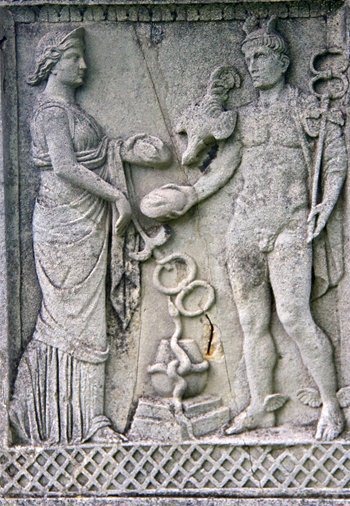

The iconography of the one considered the Gallic Mercury includes birds, notably crows and the cockerel, which has become the emblem of France. Lug also has other associations such as horses, the tree of life, dogs or wolves, as well as a pair of snakes (c.f. the Caduceus and the Abraxas of Hermes). And that without forgetting mistletoe as well as bags of money, and finally shoes (one of the dedications to the Lugoves, plural name of this ternary God, was made by a guild of shoemakers; the Welsh counterpart of Lugus, Lleu (or Llew) Llaw Gyffes, is described in the Welsh Triads as one of the "three golden shoemakers of the island of Great Britain").

Lugus is often armed with a spear and frequently accompanied by his companion Rosmerta ("great provider"), who carries the ritual drink with which royalty was conferred in Roman mythology. Unlike the Roman Mercury, who is always young, the Gallic Mercury is sometimes also depicted as an old man.

Triplicity

The number 3 was a significant and powerful number for the Celts and a host of other ancient civilizations. The number was considered sacred, so anything that appeared in three parts was a representation of great religious value. A range of Celtic deities appeared in threes, such as the three-horned bull in Celtic Britain or the Gallic mother Goddesses, the latter having more than a hundred different names. They are called Matrae, Matres or Matronae after the Roman conquest.

The number 3 indicates a complete cycle of past, present and future or mother, father and child. The number was also represented by three different social functions: the warrior, the sacred and the fertile, the latter sometimes represented by the farmers, who are responsible for the abundance from which everyone benefits.

The relevance of numbers goes even further. In Celtic stories, questions are often asked three times. Laws, maxims, knowledge and rules of poetry were always arranged in triads and their number was associated with luck, importance and magic.

We could also look at the symbol of Triskele and its meaning at length, but that will be reserved for another article.

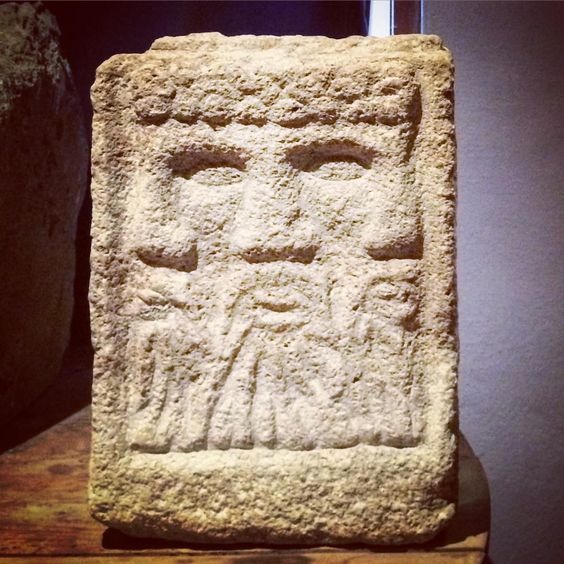

Returning to Lucubo, an altar representing a tricephalous God identified as Lugus was discovered in Reims, France. This multi-headed representation is one of the main arguments for his association with Mercury in the Gallo-Roman cult. Indeed the latter is associated with triplicity: he has sometimes three faces, sometimes three phalluses, which may explain the plural dedications.

The phallus, by the way, which had a very different meaning at the time, was a symbol of the male sex of course, but also of fertility, as the menhir of Saint-Samson-sur-Rance shows us. The latter has nevertheless been degraded and smoothed to become a Christian cross, its original form being phallic. This menhir was used by women as a fertility stone; they came to rub it to have children.

Among the Ancients, Greeks and Romans, phallic representations also had an apotropaic virtue (to ward off evil spirits), so much so that they were frequent at the entrance to houses, and were often worn as amulets around the necks of children.

Finally, the phallus was a symbol of virile qualities. This association is indeed very obvious in the light of Greek aesthetics, like the Corinthian helmet, worn by a female deity, Athena.

Outside of Gaul, Lugus is also compared to his equivalent Irish myth. In some versions of the myth, Lug was born as a triplet, and his father, Cian - ("Distance"), is often mentioned along with his brothers Cú ("Dog") and Cethen (meaning unknown), who have no history of their own. Several characters called Lugaid, a popular name in medieval Ireland that is said to derive from Lug, also display a ternary nature. For example, Lugaid Riab nDerg ("red stripes") and Lugaid mac Trí Con ("son of three dogs") both have three fathers.

Ludwig Rübekeil, a German philologist, suggests that Lugus is a Trinitarian God, comprising Esus, Toutatis and Taranis, the three main deities mentioned by Lucan (who, at the same time, makes no mention of Lugus). His theory also suggests that pre-proto-germanic tribes in contact with the Celts (perhaps the Chatti, fearsome foot soldiers, who gave birth to present-day Hesse and Franconia above the Main) shaped aspects of Lugus by incarnating them in the Germanic God Wōdanaz. The Gallic Mercury would thus have given birth to the Germanic Mercury.

Sacred sites and continuity in Celtic myths

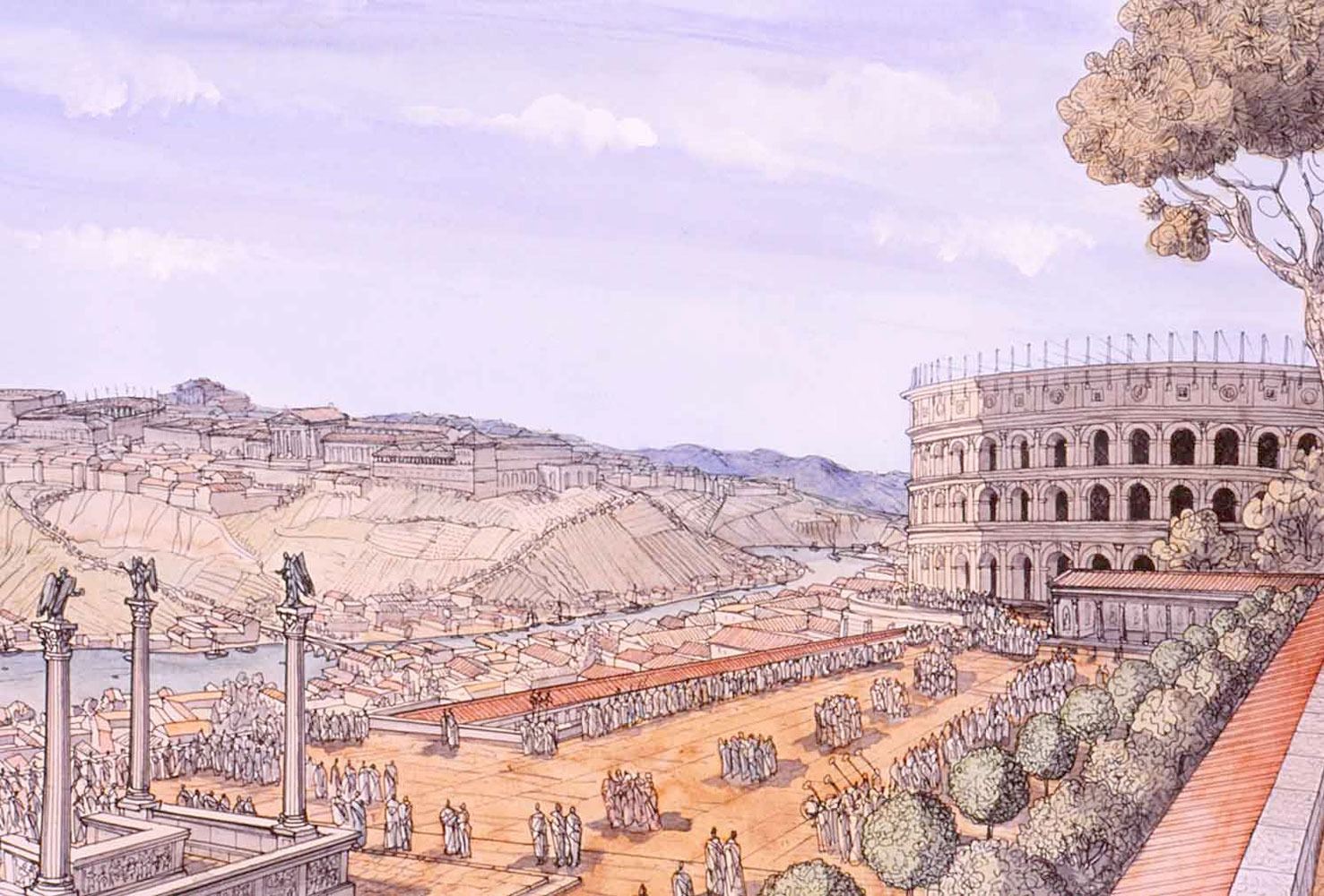

High places, called Mercurii Montes, have been dedicated to the God Lugus, like Montmartre, the Puy-du-Dôme and the Mont de Sène.

- In Ireland, Lugh is the young winner who beats the monstrous Balor "of the poisonous eye". He was the pious paradigm of sacerdotal royalty, and another of his appellations, lámhfhada "of the long arm", takes up an ancient proto-indo-european image of a noble ruler extending his power far and wide. His feast, called Lughnasadh ("Festival of Lugh") in Ireland, is commemorated on 1 August. When Emperor Augustus inaugurated Lugdunum ("Fort of Lugus", now Lyon) as the capital of Roman Gaul in 18 BC, he did so with a ceremony on 1 August (this may, however, be purely coincidental). At least two of the ancient sites of Lughnasadh, Carmun and Tailtiu, were supposed to house the tombs of Goddesses related to earthly fertility.

- In Wales, it was also thought that Lugus may have been the origin of not only Lugh and Lleu Llaw Gyffes. According to another theory, it could even have given birth to Arthurian characters, namely Lancelot and King Lot (whose most famous champion is the Arthurian scholar Roger Sherman Loomis). More recent Arthurian studies, however, have downplayed any such link between Lugus and Lancelot.

- The hypothesis in the Gallo-Roman world is that the God Lugus, appearing in Irish mythological texts, would correspond to the Gallic deity whom Caesar identified as Mercury, "the inventor of all the arts". This theory is reinforced by epigraphic evidence. Indeed, an inscription of Osma, a town in the province of Soria in Spain in which the consecration to Lugoues, the plural form of the name of the triple divinity, was made by a guild of shoemakers. Without forgetting the numismatic evidence that seems to confirm the relationship between Lugus and this profession. Furthermore, these coins show on the obverse a radiating bust of Postumus and on the reverse a male figure without a beard, with wavy hair and large hands. The God holds a trident upwards in his left hand and a bird in his right hand, on his left shoulder rests another bird from which two belts hang, the legend of the coin is SVTVS AVG, which means Sutus Aug(ustus) or "divine shoemaker".

In addition, fragments of the Mabinogion, written in Wales around the XIIth or XIIIth century, can be interpreted in the same vein. As in the case of medieval Irish manuscripts, authors have claimed that the tales of the Mabinogion were based on legends that had been circulated orally centuries before. In these texts, a character named Llew Llaw Gyffes appears similar to Lug. His name also means "The Shining One" and, like Lugus, Llew is disguised as a shoemaker in one of the stories.

An engraved lead plate found in Chamalières, France, contains the expression luge dessummilis, which has been tentatively interpreted by some scholars as "I prepare them for Lugus", although it may also mean "I swear (luge) with/by my right hand".

Functions

Identified as a multifunctional deity, Lugus was identified with Mercury, the latter having a series of sculptural representations in which one of his most striking characteristics is his triple face. This theory is supported by Caesar, who considered the Gallic God Mercury to be the most venerated God, since there were more stone and bronze images of Mercury in Gaul than of any other deity.

We can also detect the plural form of Lugus in the altars found in the province of Lugo in the region of Galicia in Spain, where the God is cited as Lucoubu Arquieni, Lugubo Arquienobo and [...]u Arquienis. Even more important are the three foculi (ovens used to burn religious offerings) identified in the upper part of two of the altars, which allow us to hypothesize that the plural dedications found in Lugo are comparable to those dedicated to the denomination Matrebo Nemausikabo found in Nîmes.

Lugoues probably represented a type of deity similar to the Matres who were linked to Lugus, and who, as the son of Talltiu, which has been considered as the Mother Earth by J. Loth, French linguist and celtologist, was probably as much a Chthonian God as a celestial God. The consecrations to the Goddess Maiabus found in Metz must also be interpreted in the same sense, since they are probably linked to Maia, the mother of Mercury, with whom he seems to be associated in many Gallic inscriptions. A close relationship existed between the clues linked to the Gallo-Roman three-faced God and the Matres, which are perhaps a transposition of the great Celtic ternary God.

It should be noted that the theories that identified the plural denominations of Lugus with the cult of the Matriarchs gained considerable support with the recent discovery of a votive altar dedicated to Lugunis deabus in Spain at Atapuerca, Burgos. Atapuerca being in the heart of the Hispanic territory where the cults of Lugus and the Matres were the most intense.

In conclusion, Lugus plays an essential role in the solar movement. The God proclaims during an epiphany reported in The Foundation of the Domain of Tara (Suidigud Tellaig Temra) "to be the cause of the rising and setting of the sun." It is also known that he intervenes in the passage from night to day. As the agent of the dawn that brings light and, in general, the beautiful season and life, Lug ensures the birth of a stable and balanced society, governed by seasonal alternation.

Lug appears as a psychopomp divinity "who accompanies souls in the Beyond, as he accompanies the sun in the twilight that marks its passages between darkness and light".

Archetype of the Lawful Sovereign, Lugus also takes after the child prodigy because he is a virtuoso in many fields such as creation, music, exchanges, thought and beauty. He is also a magician because he is a master of healing, a warrior because of his equine and warlike associations, and finally a craftsman who can also be vindictive and obscure. According to Caesar, he also "points the way, the way that guides the traveller, and he is the one most capable of making money and protecting trade."

You will find the presentation of the other Celtiberian deities in the next parts.

Juan Carlos Olivares Pedreño, University of Alicante

Alberto J. Lorrio, Universidad de Alicante Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero, Universidad Complutense de Madrid

https://herminiusmons.wordpress.com/

https://goldentrail.wordpress.com/

Prósper, B. M.: Lenguas y religiones prerromanas del occidente de la Península Ibérica

Alarcão, Jorge de.: A religião de Lusitanos e Calaicos