The Bay Area town that drove out its Chinese residents for nearly 100 years

Katie Dowd, SFGATEApril 7, 2021Updated: April 7, 2021 10:44 a.m.

Antioch Historical Society & Museum

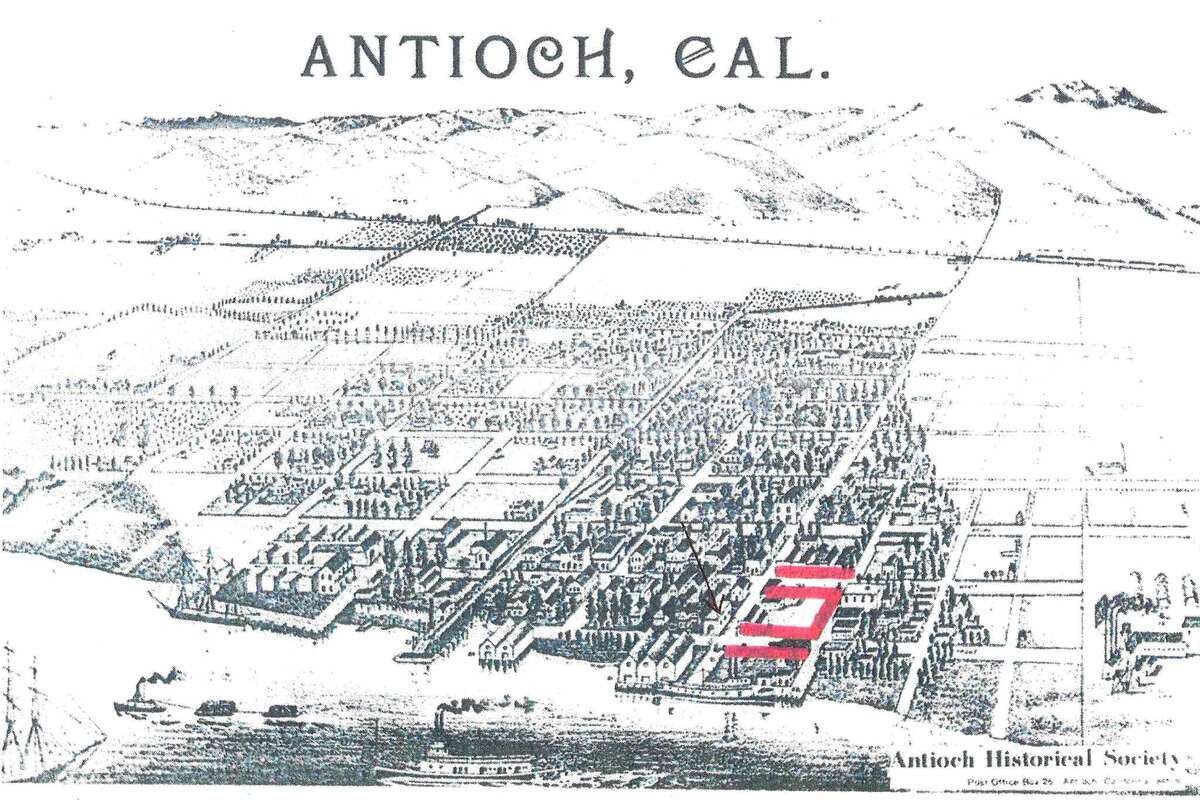

Before the white residents of Antioch burned down Chinatown in 1876, they banned Chinese people from walking the city streets after sunset.

In order to get from their jobs to their homes each evening, the Chinese residents built a series of tunnels connecting the business district to where I Street met the waterfront. There, a small Chinatown and a cluster of houseboats made up the immigrant settlement. If they ever felt safe there, it was fleeting. Above the tunnels and outside their doors, the threat of violence was simmering.

"The citizens of Antioch have been endeavoring to rid themselves of the Chinese for some time,” the Sacramento Bee wrote in the spring of 1876.

Antioch Historical Society & Museum

The excuse they were waiting for came on April 29, 1876. According to newspaper reports, a doctor in Antioch made public the knowledge that a handful of young men he treated showed signs of venereal disease. The doctor pointed the finger at Chinese sex workers; he knew what he was doing.

Outrage ripped through the town. A mob quickly formed. Some urged murdering the women, but “better counsels prevailed,” a wire report recounted. Instead, the swarm of four dozen angry white men went door to door in Chinatown, telling the occupants they had until 3 p.m. to leave town — no exceptions. Young, old, men, women, healthy and deathly ill had just hours to pack up and depart.

It must have been an eerie sight: a crowd of frightened Chinese immigrants, their belongings knotted up into kerchiefs, standing silently in line at the dock, awaiting ferries to San Francisco and Stockton.

"The lightning of Caucasian wrath upon Mongolia has struck," the Mercury News wrote. But the spark it ignited had only just started to burn.

---

Read More

In the decades following the Gold Rush, no immigrant group was as loathed as the Chinese. That hatred became endemic to California, planted and nourished by politicians, city leaders and the media. Their xenophobic talking points will sound familiar today: outrage over “low skill” laborers taking jobs from white people, complaints that Chinese people failed to integrate into American society (while simultaneously barring them from schools, social gathering places and even public streets) and accusations of “an invasion.”

"Anti-Chinese sentiment is right, patriotic, and in every sense American,” the Los Angeles Herald declared in 1876.

By the 1870s, California had moved from local ordinances, like Antioch’s street ban, to creating entire anti-Chinese political parties. San Franciscan Denis Kearney, himself an immigrant from Ireland, formed the Workingmen’s Party of California. Its stated goal was to eradicate Chinese workers and its infamous slogan was: “The Chinese must go!” The state constitution ratified in 1879 had only one article that addressed a racial or ethnic group. Entitled “CHINESE,” it banned corporations from hiring “Chinese or Mongolian” people and specified "no Chinese shall be employed on any State, county, municipal, or other public work, except in punishment for crime." Three years later, the federal Chinese Exclusion Act would bar all Chinese laborers from immigrating altogether.

It was in this hateful, volatile atmosphere that white Californians began setting arson fires in Chinatowns. It was easy to burn down entire settlements because laws often restricted what parts of town they could live in, clustering everyone in the same few blocks.

The day after Antioch’s Chinatown was emptied, it was physically eradicated. As churchgoers left Sunday services, rumors began to spread that some Chinese residents had returned home. No one now living can reveal what exactly happened next. But by 8 p.m., someone had set Chinatown on fire.

A crowd of onlookers and the local fire brigade looked on as flames engulfed homes and buildings. “Very little was done to stay the progress of the fire,” a wire report noted, although crews must have gone into action at some point to prevent white homes and businesses from being damaged. "The Caucasian torch," wrote the Bee, "lighted the way of the heathen out of the wilderness."

By morning, all but two of Chinatown’s buildings were razed. The news was met with enthusiasm throughout the state.

"The actions of the citizens of this place will, without doubt, meet with the hearty approval of every man, woman and child on the Pacific coast," the Chronicle cheered, "and will go a long ways toward convincing the people of the Eastern States that the Chinese nuisance on our seaboard has assumed such vast proportions that it is beyond the pale of political issues and has come to be a disgrace that must be wiped out."

A few newspapers cautioned that legislation, not arson, was the preferred way to eliminate Chinese people from their communities. The only prominent voice against the Antioch violence was San Francisco’s famed Emperor Norton, although his grievance was also colored by economic concerns.

"The Antioch riot is a disgrace to Americans," he wrote in an Oakland Tribune op-ed. "Now, therefore, We, Norton I., Dia Gracias Emperor, do hereby command the Grand Jury of Contra Costa County to indict the anti-Chinese leaders and have them brought to justice, and thereby protect the Americans and other foreigners and commerce in China."

For their part, the citizens of Antioch were largely unrepentant. The Antioch Ledger blamed the Chinese residents for the arson attack, writing, "had the women not returned, the property would have remained intact." A few days later, they lied again.

“A large number of Chinamen quietly pursue their avocations in our midst, unmolested,” they wrote. “No Chinaman has ever been interfered with."

---

Antioch Historical Society & Museum

The events of 1876 had a century of ramifications for the demographics of Antioch. Although some Chinese people did eventually return to do business in the area, almost none felt safe permanently settling there again. Nearly 100 years later, the 1960 census recorded a little over 17,000 people living in the town; 99.6% were white. Just 12 residents were Chinese.

That finally began to change, however, in the '80s and '90s as Antioch’s population boomed. The Contra Costa County town, ideal for commuters who couldn’t afford San Francisco real estate prices, grew and changed. Sixty-two thousand people lived there in 1990 and 3,043 identified as AAPI.

The 2010 census showed white people had become the minority for the first time; 10% of the population is Asian American.

Below the waterfront part of town, some of the tunnels were occasionally resurfaced by construction work. They were remarkably sturdy with entrances framed in brick. During Prohibition, they were supposedly used by rum runners.

They were built, it seems, for centuries of use.