The Augustinian Settlement

Nathan Goldwag3,498 words | Jul. 01, 2024 | nathangoldwag.wordpress.com

In 30 BCE, the armies of Octavian decisively defeated Mark Anthony at the Battle of Actium. By the end of the year, both Anthony & his lover Cleopatra had killed themselves, & the young heir of Caesar stood triumphant over the Roman world, having finally won the cycle of civil wars begun in 49 BCE, with the crossing of the Rubicon. Octavian would return in triumph to Rome, & in 27 BCE, the Senate would bestow upon him the name “Augustus”, symbolizing his new unquestioned power over the State.

In history books, this year marks a firm transition–from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire, with Augustus taking his place as the first Emperor of Rome. But Augustus’ reign is as notable for its continuity as it is in its reformation. The “Empire” as a distinct state was never established, & neither was an actual office of “Emperor”, & Roman writers continued to refer to the res publica for centuries. The mechanisms, traditions, & institutions of the Republican system were maintained wholesale, & the regime was defined by its adherence to tradition & stability, promising, if anything, a restoration of ancient virtue. This was, however, done in tandem with Augustus’ establishment of direct, personal rule of the state by himself, which his heirs would maintain for centuries.

I think it’s worth taking a close look at exactly how this was done, & how it may have been seen or convinced of by contemporaries. Historians have a tendency to look backwards with hindsight. We know that the Augustinian Settlement formed the basis of a hereditary monarchy that lasted for centuries, & so we see it primarily in that context. But is that too simplistic a view?

Octavian’s imperium (in the original Roman sense, meaning formal state power to command troops & other govtal entities) was first established by the Lex Titia, passed in 43 BCE to create the Second Triumvarite. This law granted Octavian, Mark Anthony, & Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, leading partisans & warlords of the late Julius Caesar, wide-ranging authority over the Republic, with the right command provinces & command military forces, enact legislation by decree, & appoint magistrates without appeal. But this was, to be clear, a blatant military dictatorship, established at sword-point after Octavian’s forces captured Rome, & inaugurated by a bloody purge of their political enemies in the Senate. The Roman Republic was at this point in something close to a terminal breakdown; split between the Triumvarite, the Liberatores, & Sextus Pompey.

The civil war begun in 49 BCE continued, a spiraling cycle of endemic political violence that seemed to have no end. The Triumvarite marched against the Liberatores, Mark Anthony fought Parthia, & lost, Lepidus overcame the remaining Pompeians on Sicily, only to be betrayed & sidelined by his partners, & finally open warfare between Octavian & Mark Anthony erupted, ending with Octavian’s victory. But this had happened before, in 45 BCE, with Julius Caesar’s triumph, which had come crashing down mere months later with his assassination. That Augustus’ reign did not collapse, but instead endured for centuries, can be credited to a no. of factors, not the least of which was his shrewd political instincts.

When Julius Caesar had seized Rome in 49 BCE, he had been declared dictator, initially in a series of annual appointments, but eventually formalized as dictator perpetuo, dictator-for-life–ironically, mere months before his assassination. “Dictator” was a very old & traditional Roman political office, though Caesar’s use followed from Sulla’s revival of the office in 82 BCE, which was very different in power & structure from the original.

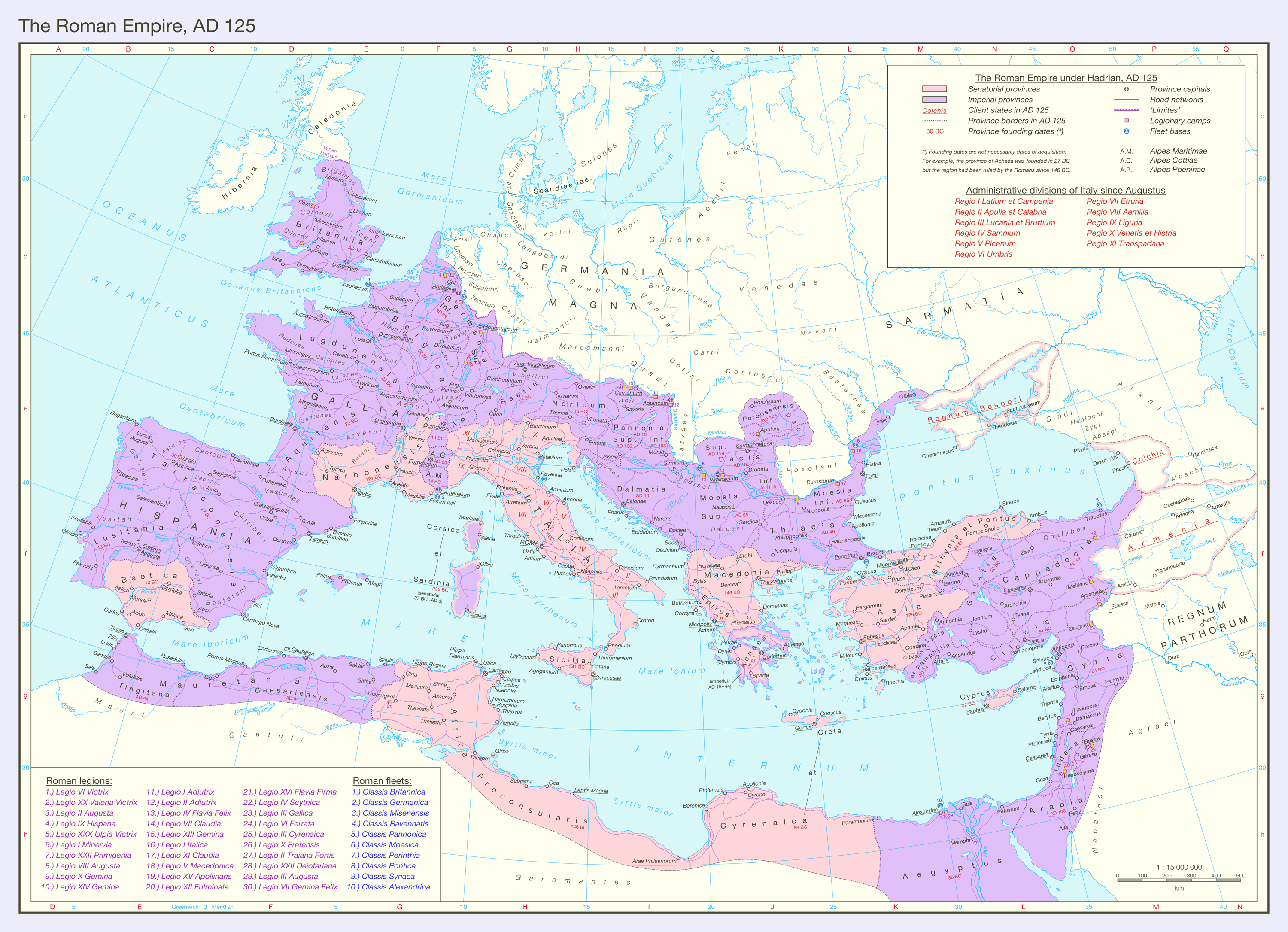

Augustus eschewed any singular supreme office–perhaps remembering what had happened to his great-uncle. Instead, he accumulated many threads of power, working within the structure & form of traditional republican politics to create an unassailable position of strength. In 27 BCE, he formally resigned the extraordinary powers of the Triumvirate, now that the crisis had passed. Instead, the Senate “granted” him the governorship of all of Iberia, Gaul, Syria, & Egypt for a period of ten years, which formalized his command of the vast majority of Roman legions. Augustus would govern these provinces by appointed legates, while the Senate would continue to appoint magistrates to the remaining provinces. His imperium was initially guaranteed by his yearly election as one of the two consuls, from 31-23 BCE, after which he stood down from that office, & encouraged the resumption of regular elections.

The distinction between Senatorial & Imperial provinces endured for centuries (Source)

To enable him to continue to hold his provincial commands–which were regularly renewed every ten years–the Senate granted him maius imperium proconsulare, permanent proconsular authority defined as greater than that of any other magistrate. At around the same time, he was awarded tribunician powers as well, granting him the rights & authority of a tribune of the plebs. In 12 BCE, he added the position of pontifex maximus, the high priest of the College of Pontiffs, to this collection. This gradual consolidation of authority was, perhaps most famously, summed up by the Roman historian Tacitus:

When the killing of Brutus & Cassius had disarmed the Republic; when Pompey had been crushed in Sicily, &, with Lepidus thrown aside & Antony slain, even the Julian party was leaderless but for the Caesar; after laying down his triumviral title & proclaiming himself a simple consul content with tribunician authority to safeguard the commons, he first conciliated the army by gratuities, the populace by cheapened corn, the world by the amenities of peace, then step by step began to make his ascent & to unite in his own person the functions of the senate, the magistracy, & the legislature. Opposition there was none: the boldest spirits had succumbed on stricken fields or by proscription-lists; while the rest of the nobility found a cheerful acceptance of slavery the smoothest road to wealth & office, &, as they had thriven on revolution, stood now for the new order & safety in preference to the old order & adventure. Nor was the state of affairs unpopular in the provinces, where administration by the Senate & People had been discredited by the feuds of the magnates & the greed of the officials, against which there was but frail protection in a legal system for ever deranged by force, by favouritism, or (in the last resort) by gold.

The Annals of Tacitus, Publius Cornelius Tacitus, Book I, pg. 246 (Source)

This was an unprecedented concentration of political & personal power, but it’s worth noting what it wasn’t, as well. Augustus did not have (legal or formal) command over the Senate or Assemblies, from which his power (legally) flowed. He did not actually have administration over the senatorial provinces, though his grant of proconsular authority made him senior to any of their governors. To say he was not a monarch is not sophistry or pedantry, he presented himself as chief magistrate of the res publica, as someone who’s authority ultimately flowed from it. There was no separation between Augustus & other Roman elites, in the sense of a noble court or by royal blood, he continued to operate like any other Roman politician-aristocrat, simply one who possessed far greater power & prestige than any of his peers. The Great Chain of Being, this was not. Increasingly, the term princeps came to be used to define his position, meaning roughly “first citizen”, or “first among equals”. In private letters, he sometimes described himself as “holding a sentry post”, serving as a kind of watchman over the state.

That Augustus was superior to, but not superior over, other Roman elites was important. In the hierarchical, status-obsessed world of Roman politics, it was understood that you would sometimes be outranked by other people. But it was intolerable to be controlled by them, a fundamental loss of libertas that implied that one was the equivalent of a slave.

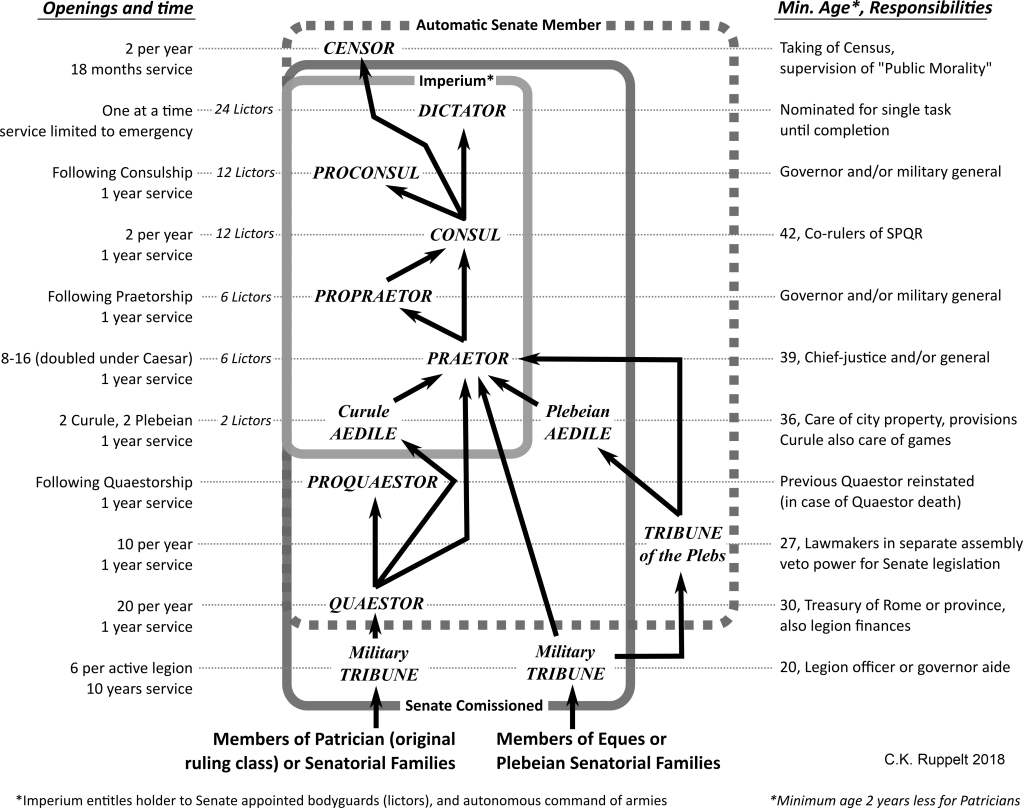

If one was being uncharitable, one could describe the Roman Republic as a system for elite competition disguised as a state. For aspiring Roman aristocrats, the goal was always to climb the cursus honorum, the “course of honors”, the sequential ladder of public posts that provided prestige & power. By maintaining the republican system, Augustus ensured that this system continued to function. Young men could pursue their ambitions within the traditional framework they expected, & win the honors they were accustomed to–something often lacking during the chaos of the civil wars, or in the unrest of the second century BCE. By gathering so much power & prestige that he could not be challenged, Augustus made the process safe again, removing the win-or-die stakes that had become increasingly prevalent in the cutthroat world of Roman politics. Throughout his reign, elections were held regularly, & there are multiple reports of violence & bribery marring them, which suggests that they were still being vigorously contested. Augustus’ resignation of the consulship in 23 BCE helped maintain this system, clearing the way for others to hold this key honor, & this choice of successor helped reflect that.

Sestius had been Brutus’ quaestor & had fought for him against the young Caesar [Octavian]. Although he had surrendered after Philippi & been pardoned, he was still open & enthusiastic in his praise of the dead Liberator, keeping images of Brutus in his house & delivering regular eulogies. The choice of such a man who most clearly not a crony of the princeps was widely admired, especially by the aristocracy.

Augustus: First Emperor of Rome, Adrian Goldsworthy, pg. 267

None of this is to dispute the very real power over the Roman state that Augustus had, which was ultimately backed up by his personal control of the legions. But the form that that power took, & the methods he used to legitimate it, are important.

The govt of the Roman Republic had been built on diffusion of power, an interlocking & overlapping system of assemblies & elected magistrates that made it nearly impossible for any one man to gain control over the commonwealth. (We don’t have time to explain how it all worked here, but I recommend this series of articles). At least, that had been the theory. But following the crushing series of Roman military successes in the Punic, Macedonian, & Antiochene Wars over the course of third & second centuries BCE, the Republic had struggled to adapt to its new hegemonic reality. The result had been a series of “extraordinary magistracies”, driven both by intra-elite political feuds & major domestic & foreign crises. Gaius Marius served an unprecedented five consecutive terms as consul from 104-100 BCE due to the Cimbrian War. His onetime subordinate & eventual rival Sulla fought a series of civil wars against his allies & partisans, which ended with the Senate appointing him dictator legibus faciendis et reipublicae constituendae causa (“dictator for the making of laws & for the settling of the constitution”), a position of unprecedented scope & power, which he held from 82-80 BCE. In 60 BCE, three of the most prominent politicians in Rome, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Marcus Licinius Crassus, & Gaius Julius Caesar, formed an informal political alliance later dubbed “The First Triumvirate”, which dominated the Republic until 49 BCE. As part of this, Pompey was given provincial command of the provinces of Hispania, & allowed to govern it via legates (a previously unthinkable arrangement), & served as sole consul in 52 BCE, while Caesar governed the provinces of Cisalpine Gaul, Transalpine Gaul, & Illyria for a decade. And, of course, after his victory in the subsequent civil war, Caesar ruled as dictator intermittently from 49-45 BCE, which was followed by the establishment of the Second Triumvirate in 43 BCE.

The point is that, by the time Augustus took power, the Roman Republic had been dominated by extraordinary magistracies for a generation. It had become part of the nature of republican politics, & Augustus merely differed from his predecessors in the scale & scope of his power, & his success in consolidation. Rome lacked a written constitution, though it had a strong sense of tradition & custom, called sometimes the mos maiorum, “the way of the ancestors”. As unwritten norms eroded, it become hard to determine which acts of the Senate & assemblies were legitimate or not, leading to absurd situations such as the aftermath of Caesar’s assassination, where the Senate pardoned his murderers & simultaneously ratified all decisions he’d made while dictator.

It worth looking at how Augustus himself commemorated his record, & how he presented his successes to both the Roman public & to posterity:

At the age of nineteen, on my own initiative & at my own expense, I raised an army by means of which I restored liberty to the republic, which had been oppressed by the tyranny of a faction.

—

The dictatorship offered me by the people & the Roman Senate, in my absence & later when present, in the consulship of Marcus Marcellus & Lucius Arruntius, I did not accept.

—

When the Senate & the Roman people unanimously agreed that I should be elected overseer of laws & morals, without a colleague & with the fullest power, I refused to accept any power offered me which was contrary to the traditions of our ancestors. Those things which at that time the senate wished me to administer I carried out by virtue of my tribunician power. And even in this office I five times received from the senate a colleague at my own request.

Res Gestae Divi Augusti (Source)

This is, of course, propaganda. But propaganda can be important. It tells you what people value, & how they wish to be seen, & what they think is important.

In addition to this formal apparatus of power, Augustus possessed a vast reservoir of informal prestige & status that allowed him to bend the state to his will without having to resort to force. The term here used is auctoritas, which is usually translated as “authority”, but more properly refers to the prestige, status, & personal standing of a Roman citizen. This was a hugely important concept in republican politics, & it was well-understood that your ability to command respect & allegiance as a politician was based on your personal auctoritas; your accomplishments, victories, virtues, your family’s history & pride, & your networks of patrons & clients. Augustus had power unprecedented in Roman history, but he also had auctoritas unprecedented in Roman history, a record of accomplishments & victories that had restored peace to the res publica after decades of civil unrest, & a personal network of clients & allies that stretched across the Mediterranean. In this sense, his legal position as princeps becomes almost inevitable, the natural consequence of his personal influence & success.

The elite politics of the Republic were intensely anti-monarchical, but were in no sense anti-dynastic or opposed to nepotism. You were, as a Roman aristocrat, expected to live up to the deeds of your ancestors, & to help your sons succeed yours. Augustus, as Octavian, first entered Roman politics at the age of nineteen, when Julius Caesar’s will was opened, & it left him as the dictator’s primary heir. This was not a political succession, but it was a personal one, & it allowed Octavian to step into a position of leadership in the Julian party. Hereditary succession was not part of the Roman political tradition, but seeking to fill the same offices & honors as your father was. For Octavian, heir to Julius Caesar, the most consequential man in the Republic, these two principles became blurred, & hard to disentangle.

That Augustus’ power was not monarchical in nature can be seen by the way he exercised it, which is to say, rarely alone. He was always clearly the premier magistrate of the Republic, but carried out his (extensive) duties through delegation & assistance by a network of close friends & family members. Most notable of these was Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, a close ally & extraordinarily loyal subordinate, who stood by Augustus’ side since before his rise to power. He was eventually granted many of the same powers as his patron by the Senate, who conferred upon him the maius imperium proconsulare & tribunicia potestas, making him, in essence, the princeps‘ junior colleague. It’s an interesting echo, both of the dual consulate of the Republic, & the dual emperorships that would become increasingly common in the Imperial period. If Agrippa had not predeceased Augustus, dying in 12 BCE, he likely would have succeed him as the premier magistrate of the res publica.

Historians like to speculate about the drama surrounding the question of succession–Augustus, over the course of his regime, raised up to prominence a no. of young relatives & colleagues, most of whom ended up dying untimely young. But as Adrian Goldsworthy reminds us, we’re looking at this with the benefit of hindsight.

There is not the slightest hint than any of them was ever marked out as his sole successor, & that the others were expected to stand aside & accept one man’s pre-eminence. Not all were equal, but in theory all would be united & serve for the common good…………..He led the state with the close assistance of men drawn from his family circle whose loyalty to him was certain, & seems to have expected this arrangement to continue after his death. There would not be one princeps, but several principes, able to share the arduous responsibilities & by their existence showing that the death of the most senior would not create a power vacuum & invite a return to civil war.

In a sense it was a very Roman concept–less a monarchy than the rule of a small, informal college, each with monarchic power–& under Augustus it worked. Subsequent attempts to revive the system invariably failed, primarily because no one else ever enjoyed the same prestige as Caesar Augustus.

Augustus: First Emperor of Rome, Adrian Goldsworthy, pgs. 360-361

When Augustus died in 14 CE, the powers of the principate passed to his stepson, Tiberius. While an effective ruler, Tiberius lacked the deft touch of political mgmt that his predecessor had demonstrated. Augustus had–following the bloody purges of his early reign–treated the Senate & his fellow elites as respected colleagues, rather than subordinates. This was the system & the ethical-political framework that he had grown up under, after all. Tiberius was raised in a Republic under the undisputed rule of the princeps. In one of his first acts, he stripped the power of elections from the popular assemblies, moving them to the Senate, ending much of the political machinery of the Republic. He later moved himself to a villa outside Rome itself, ruling through subordinates & favorites, & making frequent use of legal & military force to crush opposition, real or imagined. It was a separation that could not easily be reversed.

In histories of the Roman Empire, it is usually split into two phases: the principate & the dominate. The former refers to the Empire from the reign of Augustus to the Crisis of the Third Century, during which many of the forms & traditions of the Republic were maintained. The dominate emerges in the Late Empire, when the hierarchical & monarchical nature of Imperial authority became more & more open & pronounced. But it perhaps makes sense to see Augustus’ reign as part of neither, a sort of transitional period of republican dictatorship.

These distinctions are important to make, I think, because the usual narrative undersells what a remarkable accomplishment the Augustinian Settlement was. Augustus was a warlord in an age of warlords, who first came to prominence at the age of nineteen (in a society that put a great deal of emphasis & importance on seniority & deference to age), who spent his first few years in public life exterminating his enemies & performing with only marginal competence on the battlefield, & yet who managed to finesse a method of autocratic rule that operated within the customs & conventions of the res publica.

That the Roman Republic survived the first century BCE–which was marked by endemic civil war, civic disorder, rebellion, foreign invasion, & political paralysis–& went on to the rule the Mediterranean World for another four centuries was by no means foreordained. We all talk a lot about how & why the Roman Empire fell. But maybe we should spend some time looking at how it emerged, as well. It’s a story that’s just as interesting, & maybe as important. ⚪️