Thailand Lesbian Love

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Natasza Parzymies360°180 тыс. просмотров

Киностудия Горького•623 тыс. просмотров

Natasza Parzymies360°143 тыс. просмотров

Пятый канал Россия•1,4 млн просмотров

Яблоко Любви HDНовинка972 тыс. просмотров

СМОТРИМ. Русские сериалы•26 млн просмотров

GlobalGayz is a travel and culture website focused on LGBT-Gay life worldwide: In-person Stories, archived News Reports and Actual Photos. Life, Sites and Insights.

Intro: Lesbians present a different scene than the men. More modest in their sexual expression, there are no lesbian saunas where women walk around in towels cruising each other, although there are lesbian bars. Various reasons have been offered to explain this difference, from men’s more predatory nature to feminist distaste for imitating male habits to women’s natural nurturing subjective demeanor versus men’s penchant for objectifying sex—or powerful social traditions that shape and limit women’s roles in society.

The two stories presented here focus on lesbians in Thai culture and the search for an identity that is unique to women who love women.

The first report is more recent (2004) and the second is more than 15 years old. However much of the insight and ideas described here, in both stories, are still very much current in Thailand culture and society.

Both stories examine the organization called Anjaree, a native Thai women’s association that centers on women who love women. It was founded by Anjana Suvarananda, (nicknamed ‘Pitang’) who is Thailand’s most well know lesbian activist.

For years she has been vocal and out with no fear. She has thrust herself into a public role of gadfly, challenging stereotypes of gay people among politicians and health workers and among lesbians themselves challenging the subservient roles imposed on women, demanding equal rights and awareness of LGBT issues.

Much to her credit, her lobbying and smooth-tongue persuasions resulted in a remarkable change in the ministry of health when it deleted homosexuality as a “permanent mental illness” from its diagnostic categories. It is now seen as an alternative variant of society.

Anjaree is Pitang’s social and political organization that is in contant motion to educate the public about the truth of homosexuality and to bring awareness of safe-sex behaviors. As much as rural Thailand is ignorant of family planning, they are even more ignorant about HIV and its infection means and less about homosexuality. Most rural lesbians marry and have children without ever having the awareness or choice how to manage their emotional lives. Pitang strives to change that.

January 1, 2003

By Jillana Enteen

Women’s Studies Center

State University of New York

Anjaree is the only Thai organization specifically targeting women who love women. Headquartered in Bangkok, it has members throughout Thailand, providing information, encouraging community formation, and sponsoring social events for Thai women who love women. In Thai, Anjaree means “women who follow nonconformist ways.”

Despite the organization’s entrenchment among Thailand’s women who love women-it has existed for over a decade and boasts a membership of over 500-its founder, spokesperson, and leader, Anjana Suvarananda, (nicknamed ‘Pitang’) complains that she is at a loss for words, in Thai and in English, that adequately describes her identity as a woman who loves women following nonconformist ways.

At the Sixth International Conference for Thai Studies, she presented a new Thai word that she created, yingrakying, hoping it will circulate as a new word for women “who have erotic feelings or love feelings for other women.” While Anjana often invokes the common word ‘lesbian’ when portraying herself and members of her organization to farang (Westerners), she avoids the term if given the opportunity to describe the site specific situation in Thailand. When speaking in Thai and to Thai people, she resists using the word lesbian.

Though widely understood, many Thais, including those involved in women-centered relationships, consider it vulgar and derogatory. When talking to Thais, Anjana employs and revises the commonly used Thai words for women who love women. Rather than perpetuating the use of these established terms and the stereotypes that accompany them, Anjana addresses the changing situations of Thai women who love women. At this meeting she stated: “We are not sure if this [new] term will go down well or if this will be the term we stick to or not. We are in the process of building our own culture and terminologies” (Suvarananda “Lesbianism”).

The motivation to formulate a new word is partially attributable to Anjana’s experience with cultures outside Thailand. She spent time studying at the Hague, had access to Western ideas, and speaks almost fluent English. These extensive experiences inform her attempts to affect community formation by broadening the community’s way of conceptualizing itself and its individual members. Yingrakying literally means “woman-loves-woman” in Thai, originating from the erase currently en vogue with Western women-centered organizers and academics: “women who love women.”

Rather than adopting the English word and using it in Thai in the manner the word lesbian was employed, Anjana reformulates this phrase in order to match her own intentions through translation and transformation. In this case, knowledge of the English language and farang ideas become tools rather than models for linguistic community formation. Her word becomes a strategy for interaction and community building that encourages shifting the way women imagine themselves according to changing circumstances.

Yingrakying is more than a convenient new word to name something heretofore ignored-it signals an awareness of the effects of a global Western-based movement that is personalized for this increasingly outward looking Thai community.

By considering, as the editors of the special issue of Social Text, entitled “Queer Transexions,” hold, “the interrelations of sexuality, race, and gender in a transnational context.” I attempt “to bring the projects of queer, postcolonial, and critical race theories together”

In the past decade feminist, sex, and gender theories have addressed the erasure of specific bodies in terms of race and class of individuals located in the West. Even more recently, work has begun that extends this theorizing beyond Western culture and location and re-theorizes according to localized situations. Hence the notion of sexual identity is being complicated, but universalized assumptions of identity formation are still frequently applied unproblematically to non-Western cultures.

As Dennis Altman explains, “It has become fashionable to point to the emergence of “the global gay,’ the apparent internationalization of a certain form of social and cultural identity based on homosexuality” (“Rupture” 77). While this “global gay” image is being produced by both the West and the East, and its embodiment can be seen at times in Bangkok, an international gay/lesbian is a fictive construction that has no literal embodiment, nor is it manifest in all social, political, and cultural contexts.

Rather than mapping Western histories and theories unproblematically onto Thai bodies, new explanations based on the situations in Thailand must be devised. Examining the shifts in identity formation by a group of women existing in the heretofore geographic and sexual margins reveals the effects of the “globalization” of information and economies. Arjun Appadurai asserts that “the new global cultural economy has to be seen as a complex. overlapping, disjunctive order that cannot any longer be understood in terms of existing center-periphery models.” He proposes that the relationship between five terms, or landscapes, that he creates establishes a framework for looking at these global cultural flows.

Peter Jackson, Rosalind Morris. Thook Thook Thongthiraj, and Dennis Altman practice expanding the ways in which global and local cultures in Thailand are understood, re-evaluating the usefulness of using Western theories of identification to describe Thai notions of sexuality. They look specifically at Thai history and describe the changing presentations of sexualities in response to cultural events. This chapter extends this work, examining the shifting positions of women in Bangkok over the past decade as a result of increasing opportunities for education and financial stability.

It presents varied and conflicting accounts by yingrakying that delineate previously available positions, and then shows how Anjana and Anjaree suggest new possibilities through the creation of words and communities. Anjaree’s function as a social club where women could meet women provided the impetus for my increasing involvement during my tenure of research in Bangkok. I initially joined Anjaree for social reasons, having learned about it from another American woman living in Thailand. The Thai women who loved women that I knew who were not members of Anjaree were either friends from my previous stay in Thailand or friends of friends. I conducted interviews in May, June, and October 1996.

Some of the examples cited occurred while socializing during the eight months previous to my decision to consider these interactions part of my research. Most contemporary ethnographic research combines these formal and informal procedures and methods for gathering information. While Carol, an American researcher who contributed to this study, asserts that socializing, pursuing relationships, and creating unusual or startling situations by asking abrupt questions or purposely violating Thai practices is integral and productive to her work, I employed more formal procedures, acquiring most of my information through interviews that took place, for the most part, in English.

As I will explain in the section of this essay called “English Effects,” using English for the interview processes encouraged the women to speak about identity and sexuality in ways that would not occur in a Thai language setting. Many Bangkok Thais, especially the young middle class, associate English use with prosperity, the influx of daring new ideas, and an increased number of ways to articulate sexualities and genders. Because English functions as a second language, it can provide a sense of freedom.

The position of yingrakying in Thailand has changed concurrently with the rest of Thai society, particularly Bangkok. over the last decade. Between 1986 and 1996, Thailand had one of the fastest growing economies, producing a high volume and variety of export products which generated a per capita income that increased exponentially. Prosperity had the largest impact on Bangkok residents, creating a burgeoning middle class. The majority of the members of this new middle class are college educated and have access to information from around the world via uncensored Internet access, imported entertainment, and academic media, and a large influx of farang tourists as well as those from other parts of Asia.

As a result, they possess an increasingly international outlook that is reflected in their tastes and consumption. Mobile phones, Western-made cars, and Western name brand clothing are possessions of de rigeur for Bangkok professionals. Not only are Western products consumed but also “ideas, ideologies, and politics” (Pasuk and Baker 409) from outside of Thailand.

However, while some practices and expectations changed to reflect increasing prosperity and exposure, many of Thailand’s traditional societal values remained. One societal custom that conformed to the increasing need for educated, middle class expertise was women’s participation in business. In addition to managing family finances. Thai women have often been entrepreneurs and salespeople. In accordance with previous Thai practices, women often fill the increasing demand for economic expertise.

In the past decade, many women have entered the middle class workforce, enjoying the broadening opportunities for education and individual economic security. As a result, marriage, the Thai presses repeatedly report, is no longer the primary concern of women in their twenties and thirties. Many women are opting for career success, job stability, and comfortable salaries before marriage and motherhood. Middle class women, single, in their twenties and thirties, economically independent and educated, make up a large, visible part of the population of Bangkok women who love women.

The most common words to describe Thai women who love women, Tom and Dii, appeared about twenty years ago. Tom comes from the English word “tomboy” and Dii from the word “lady.” These terms roughly coincide with the English terms butch and femme, respectively, when referring to lesbian positionings: however, they are neither mere imitations of their English derivatives nor of American descriptions of butch/femme dynamics. While one woman who studied Women’s Studies in the United States believes that the positions of Tom and Dii accent and prescribe normative Thai gender roles to a greater extent than heterosexual relationships, most women assert that these positions serve to specifically illustrate and circumscribe the desires and roles of Thai women who love women. Altering English terms to name these distinctly Thai identities conforms to the Thai habit of adopting English words where no Thai word exists. For example, in the nineteenth century, when a couple was involved romantically, they would declare themselves married. No registration was required, but marriage was premised on a man’s financial commitment in return for a woman’s running a household and remaining sexually faithful.

Over time, having “boyfriends” and “girlfriends” became possible social relationships that acknowledged interest yet did not entail specific commitments, and a new word emerged. The Thai word is faen-derived either from the English word “friend” or “fan.” The meaning of this Thai word, however, does not directly reflect either English referent. Rather, it named a situation occurring for which there were no preexisting lingual referents.

Similarly, the Thai word farang comes from the French word “francais.” yet the Thai use the word farang to refer to most non-Asians, especially Europeans and Americans, in Thailand. Anjana’s attempt to coin a new word follows this same pattern, where, as Mikhail Bakhtin describes, words carry traces from their pasts and incorporate the changing histories of the use they receive: “language, for the individual consciousness lies on the borderline between oneself and the other. The word in language is half someone else’s. It becomes one’s own only when the speaker populates it with his own intention, his own accent, when he appropriates the word. adapting it to his own semantic and expressive intention”.

These words are significantly altered in the process of cultural translation. yet they still retain traces of their original meanings. Rather than imitation or replication. the use of this word illustrates what Mary Louise Pratt terms “transculturation” whereby “members of subordinated or marginal groups select and invent from materials transmitted by a dominant or metropolitan culture” (Pratt 36).

Yingrakying resonates differently in Thai than “women loving women” does in English: these terms have not been strung together before and consequently do not directly reflect the people and organizations that promote equal rights and acceptance for women loving women. Instead, this past is translated, and the history changes. Like the meaning of the terms Tom and Dii, their positions neither replicate/imitate Western butch/femme constructions nor do they exist entirely in isolation from Western forms of desire and societal positioning. The presence of intermediary or mutated positions is often overlooked in scholarship about gender and sexuality in nondominant cultures.

Recognizing this, Will Roscoe critiques scholarship about “gay” Native Americans that simplifies the depiction of Zuni genders instead of analyzing the ways in which they do not conform to a male/female binary. “Underlying these statements,” he explains, “are assumptions about cultural change based on an either/or opposition of ‘traditional’ and ‘assimilated'” (194). Rather than viewing Tom and Dii in this either/or framework, I will delineate many of the perceived parameters and particularities.

Not only are the many kinds of same sex relationships between women in Bangkok not contained by the terms Tom and Dii, the qualifications and definitions provided by the women I interviewed about what constitutes being Tom and Dii contrast and contradict rather than forming a consistent portrayal. Although the explanations about what designates Tom and Dii dissent, certain patterns emerge. For example, fashion is the most frequently cited visual indicator of Toms. Men’s style shoes, flip-flops or sandals on their feet, Toms wear large polo shirts or oxford cloth shirts tucked into loose jeans of assorted colors. Their hair is short, straight, and styled in a manner that does not require curling or drying when wet.

Toms do not carry handbags or purses, but they do wear mobile phones and pagers, which signal their middle class status, as well as car keys hanging from their belt loops or pockets, a practice otherwise reserved for Thai men. Under their shirts, they wear undershirts instead of bras, and they tend to keep their shoulders hunched slightly forward so as to diminish the appearance of curves. Despite what seem to be clearly coded visual clues signaling class-stratified positions and particular gendered practices, the Thais I interviewed did not always rely on outward appearances as clues when asked to describe Toms. Conformity to a style of dress or appearance may be provided as examples that mark them as Toms, but they do not do so conclusively.

“Active” is another consistent adjective evoked in relation to Toms. When asked to define Tom and Dii, Pari, a yingrakying who previously considered herself a Tom, said that a Tom usually takes to “active” role during sex and “does not let another woman see her body or her breasts or whatever.” Hiding their bodies, even during sex, “they wear tank tops [as opposed to bras or nothing]; they are active,” she states. Susan, an American researching gander in Thai politics, has had several relationships with Thai women and asserts that mainstream Thai society thinks: “If you’re seen as a Tom, that defines your sex in a certain way.”

She believes that there is a stereotypical set of assumptions that a general member of Thai society, if they attempted to sexualize the position, would assume, including that “This person would be active in bed.” Carol asserts that “people associate Toms with sexuality. It has a clear sexual meaning to the outside.” For her, coding oneself as Tom through appearance is not merely a fashion sta

Fucking Xvideos Brazzers

Big Ass Russian Women

Family Strokes Taboo

Mature Cuckold Pantyhose

Big Mature Masturbation

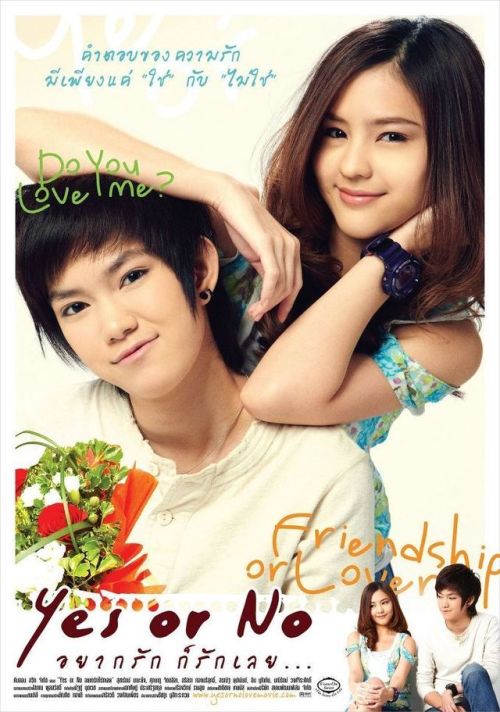

The Greatest Love Thailand Lesbian Short film - YouTube

Lesbians in Thailand - GlobalGayz

More Thai lesbian romance in She - Wise Kwai's Thai Film ...

Thailand Lesbian dating : Only Women - free lesbian and ...

Lesbian Dramas (70 shows) - MyDramaList

Thai Police Dismiss Murders of 15 Lesbians and 'Toms' As ...

Asian Lesbian-/ Bisexual Movie List (74 shows) - MyDramaList

Category:Thai LGBT-related films - Wikipedia

@LesbianInLove2 | Twitter

Thailand Lesbian Love