Sold His Wife

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wife_selling

Ориентировочное время чтения: 8 мин

Опубликовано: 22.02.2011

United States

An undated doggerel from Western Pennsylvania was reported by H. Carrington Bolton as "Pontius Pilate, King of the Jews",/"Sold his wife for a pair of shoes."/"When the shoes began to wear"/"Pontius Pilate began to swear." Bolton received it after publishing other rhymes used by children for "counting-out". Variants on the rhyme have also been reported, including from Salt Lake Cityc. 1920 …

United States

An undated doggerel from Western Pennsylvania was reported by H. Carrington Bolton as "Pontius Pilate, King of the Jews",/"Sold his wife for a pair of shoes."/"When the shoes began to wear"/"Pontius Pilate began to swear." Bolton received it after publishing other rhymes used by children for "counting-out". Variants on the rhyme have also been reported, including from Salt Lake City c. 1920 and Los Angeles c. 1935, the variants naming "Holy Moses" instead of "Pontius Pilate", and some women reported their use "as rope-skipping and ball-bouncing rhymes".

In the U.S., a folktale titled The Man Who Sold His Wife For Beef, narrated by two informants, and that possibly was true although "suspect[ed]" to be only a folktale, was told in 1952 by Mrs. Mary Richardson, living in Calvin Township, southwestern Michigan, which town was a destination for slaves travelling through the Underground Railroad and in which town most residents and local government officials were Black. As told to Richard M. Dorson, in Clarksdale, Cohoma [sic] County, northern Mississippi, c. 1890 or c. 1897–1898, a husband killed his wife and sold some parts to people to eat as beef, and the husband was caught and executed.

The plot of the 1969 western-musical film "Paint Your Wagon" treats the subject satirically.

The ride Pirates of the Caribbean at Disneyland originally contained a "Wife Auction". This was recently removed.

India

In 1933, Sane Guruji (born as Pandurang Sadashiv Sane), of Maharashtra, India, authored Shyamchi Ai, a collection of "stories", which, according to Guruji, were "true ... [but with] ... a possibility of a character, an incident or a remark being fictitious." One of the stories was Karja Mhanje Jiwantapanicha Narak (Indebtedness is Hell on Earth), in which, according to Shanta Gokhale, a man borrowed money from a moneylender, had not paid principal or interest, and was visited by the moneylender's representative who demanded full payment and "shamelessly suggested", "if you sold you[r] wife's bangles to build a house, you can sell your wife now to repay your debts", his wife, hearing this, came to where her husband and the moneylender's representative were talking and said, "aren't you ashamed to talk about selling wives? Have you no control over your tongue?", no wife sale occurred, and a partial monetary payment was made to the moneylender's representative. According to Gokhale, in 1935–1985 ("55 years") ( [sic]), "every middle-class home in Maharashtra is said to have possessed a copy of Shyamti Ai and every member of every such household may be assumed to have read it.... [and it] was also made into a film which instantly received the same kind of adoring viewership." According to Sudha Varde or Sadanand Varde, Guruji was one of "only two men ["even in the Seva Dal"] who could be called feminists in the real sense", because "Guruji ... respected women in every way .... [and] had a real awareness of the lives, of women and the hardships they had to bear"; these statements were, according to Gokhale, published as part of "some indication of the widespread influence Shyamchi Ai has had in Maharashtra."

In southeastern India, in the Tanjavur region, often described as the main part of Tamil society, according to Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Shahaji Bhonsle, who ruled Tanjavur 1684–1712, in the early 18th century wrote Satidânashûramu ('The Gifting of the Virtuous Wife'), a play in the Telugu language, for an annual festival at a temple. Subrahmanyam says that, in the play, a member of the Untouchable (Dalit) caste offers to "donate" his wife to a Brahmin and asks whether Harishchandra "didn't ... sell his wife for truth", although the Brahmin announces that he must refuse the gift and ultimately the wife's "virtue remains unsullied".

In Indian literature, Mahabharata, a story of Gandhari, according to Jayanti Alam, includes the "censor[ing] [sic]" (or censuring) of "Yudhishtira ... for 'selling' his wife in the gamble". According to Alam, "Rabindranath's Gandhari is ... a feminist" and "Gandhari's feminism reaches its sublime height and she emerges the apostle of justice".

According to Jonathan Parry in 1980, "in the famous legend of Raja Harish Chandra, it was in order to provide a dakshina that, having been tricked into giving away all his material possessions in a dream, the righteous king was forced to sell his wife and son into slavery and himself become the servant of the cremation ghat Dom in Benares."

Elsewhere

In China, according to Smith, a "possibly well-known tale" about the Song dynastic era (A.D. 960–1279) told of a wife invited to a prefect's party for wives of subordinate officials, from which she "was kidnapped by a brothel-master", who later "sold her ... [to] her husband's new employer ... who reunite[d] ... the couple".

In 1990, in Central Nepal, mainly in rural areas, one song, a "dukha", which is a "suffering/hardship" song that "provide[s] ... an interpretation of women's hardships", "underscore[d] ... the limited resources and rights of a wife caught in a bad marriage". Sung from a daughter's perspective, the song in part said, "[The wife says] You don't need to return home after drinking there in the evening."/"In Pokhara bazaar, [there is] an electricity line,"/"The household property is not mine."/"The housewife is an outsider,"/"All the household property is needed [for raksi]."/"If this wife is not enough, you can get another,"/"The head of the cock will be caught [i.e., with two wives he'll have problems]."/"Why do you hold your head [looking worried]? Go sell the buffalo and pigs."/"If you don't have enough money [for raksi], you will even sell your wife."/"After selling his wife, he'll become a jogT [here: a beggar without a wife]." A "woman ... became visibly agitated while listening to [this song]". This was part of a genre sung at the annual Tij Festival, by Hindu women in the mid to late 20th century, but mostly not between the festivals. According to Debra Skinner and co-authors, "this genre ... has been recognized by urban-based political and feminist groups as a promising medium for demanding equal rights for women and the poor."

In Guatemala, according to Robert G. Mead, Jr., a "legend [that is] popular ... [is] the story of the poor man who becomes rich by selling his wife to the Devil." This legend, according to Mead, is also one basis of the 1963 novel Mulata de tal, by Miguel Angel Asturias, a winner in 1967 of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In the Dutch Indies, fiction by Tirto Adhi Soerjo, who was Javanese and writing in a language that "was a form of resistance to Dutch", according to Laurie J. Sears, included in 1909 Membeli Bini Orang: Sebuah Cerita Yang Sungguh Sudah Terjadi Di Periangan (Buying Another Man's Wife: A Story that Really Happened in the Priangan), in which "a religious Muslim ... tries to get rid of his wife, whom a dukun said was not good for him .... [noting that since his marriage after his prior widowhood] all his business efforts have turned into failures .... [and] he agrees to give or sell his wife to a greedy Eurasian (=Indo) moneylender who has fallen in love with her.... [She, as the first man's wife,] is a very promiscuous woman, easily impressed with money and fashionable clothing, and the Eurasian ends up feeling more than punished for his pursuit and purchase of another man's wife."

In Scandinavia, in c. 1850s–1870s, where there were many critics of the Mormon religion, "ballad mongers hawked 'the latest new verse about the Copenhagen apprentice masons' who sold their wives to the Mormons for two thousand kroner and riotously drowned their sorrows in the taverns".

In English author Thomas Hardy's 1886 novel The Mayor of Casterbridge, the mayor's selling of his wife when he'd been a young, drunken labourer is the key plot element.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wife_selling_(English_custom)

Ориентировочное время чтения: 9 мин

Опубликовано: 29.10.2006

It is unclear when the ritualised custom of selling a wife by public auction first began, but it seems likely to have been some time towards the end of the 17th century. In November 1692 "John, ye son of Nathan Whitehouse, of Tipton, sold his wife to Mr. Bracegirdle", although the manner of the sale is unrecorded. In 1696, Thomas Heath Maultster was fined for "cohabiteing in an unlawful manner with the wife of George ffull…

It is unclear when the ritualised custom of selling a wife by public auction first began, but it seems likely to have been some time towards the end of the 17th century. In November 1692 "John, ye son of Nathan Whitehouse, of Tipton, sold his wife to Mr. Bracegirdle", although the manner of the sale is unrecorded. In 1696, Thomas Heath Maultster was fined for "cohabiteing in an unlawful manner with the wife of George ffuller of Chinner ... haueing bought her of her husband at 2d.q. the pound", and ordered by the peculiar court at Thame to perform public penance, but between 1690 and 1750 only eight other cases are recorded in England. In an Oxford case of 1789 wife selling is described as "the vulgar form of Divorce lately adopted", suggesting that even if it was by then established in some parts of the country it was only slowly spreading to others. It persisted in some form until the early 20th century, although by then in "an advanced state of decomposition".

In most reports the sale was announced in advance, perhaps by advertisement in a local newspaper. It usually took the form of an auction, often at a local market, to which the wife would be led by a halter (usually of rope but sometimes of ribbon) around her neck, or arm. Often the purchaser was arranged in advance, and the sale was a form of symbolic separation and remarriage, as in a case from Maidstone, where in January 1815 John Osborne planned to sell his wife at the local market. However, as no market was held that day, the sale took place instead at "the sign of 'The Coal-barge,' in Earl Street", where "in a very regular manner", his wife and child were sold for £1 to a man named William Serjeant. In July the same year a wife was brought to Smithfield market by coach, and sold for 50 guineas and a horse. Once the sale was complete, "the lady, with her new lord and master, mounted a handsome curricle which was in waiting for them, and drove off, seemingly nothing loath to go." At another sale in September 1815, at Staines market, "only three shillings and four pence were offered for the lot, no one choosing to contend with the bidder, for the fair object, whose merits could only be appreciated by those who knew them. This the purchaser could boast, from a long and intimate acquaintance."

Although the initiative was usually the husband's, the wife had to agree to the sale. An 1824 report from Manchester says that "after several biddings she [the wife] was knocked down for 5s; but not liking the purchaser, she was put up again for 3s and a quart of ale". Frequently the wife was already living with her new partner. In one case in 1804 a London shopkeeper found his wife in bed with a stranger to him, who, following an altercation, offered to purchase the wife. The shopkeeper agreed, and in this instance the sale may have been an acceptable method of resolving the situation. However, the sale was sometimes spontaneous, and the wife could find herself the subject of bids from total strangers. In March 1766, a carpenter from Southwark sold his wife "in a fit of conjugal indifference at the alehouse". Once sober, the man asked his wife to return, and after she refused he hanged himself. A domestic fight might sometimes precede the sale of a wife, but in most recorded cases the intent was to end a marriage in a way that gave it the legitimacy of a divorce. In some cases the wife arranged for her own sale, and even provided the money for her agent to buy her out of her marriage, such as an 1822 case in Plymouth.

Such "divorces" were not always permanent. In 1826 John Turton sold his wife Mary to William Kaye at Emley Cross for five shillings. But after Kaye's death she returned to her husband, and the couple remained together for the next 30 years.

The French widely believed that it was common practice for a man tired of his wife to take her to London's Smithfield to be sold to the highest bidder, but cleric/historian challenged a French cleric who claimed he had read it from a reliable source. He then asked Baring Baring Gould if he knew of the practice, and was forced to admit he had witnessed the sale of the local poet as a child. Despite both the vicar and Justice of the Peace explaining the sale was not legal, the poet insisted it to be so, and they had a happy life together.

Sales became more common in the mid 18th century, the result of husbands being abroad in the military, navy, or being transported to the colonies. It was commonly believed that an absence of 7 years constituted a divorce, so when the first husband returned to find his wife had a new family, the dilemma was solved by the first husband selling his wife in the market place for a nominal sum. It was not recognised as legal, as one wife had to wait for her first husband to die before being able to marry the father of her children. She was given away by her grandson.

Mid-19th century

It was believed during the mid-19th century that wife selling was restricted to the lowest levels of labourers, especially to those living in remote rural areas, but an analysis of the occupations of husbands and purchasers reveals that the custom was strongest in "proto-industrial" communities. Of the 158 cases in which occupation can be established, the largest group (19) was involved in the livestock or transport trades, fourteen worked in the building trade, five were blacksmiths, four were chimney-sweeps, and two were described as gentlemen, suggesting that wife selling was not simply a peasant custom. The most high-profile case was that of Henry Brydges, 2nd Duke of Chandos, who is reported to have bought his second wife from an ostler in about 1740.

Prices paid for wives varied considerably, from a high of £100 plus £25 each for her two children in a sale of 1865 (equivalent to about £14,400 in 2021) to a low of a glass of ale, or even free. The lowest amount of money exchanged was three farthings (three-quarters of one penny), but the usual price seems to have been between 2s. 6d. and 5 shillings. According to authors Wade Mansell and Belinda Meteyard, money seems usually to have been a secondary consideration; the more important factor was that the sale was seen by many as legally binding, despite it having no basis in law. Some of the new couples bigamously married, but the attitude of officialdom towards wife selling was equivocal. Rural clergy and magistrates knew of the custom, but seemed uncertain of its legitimacy, or chose to turn a blind eye. Entries have been found in baptismal registers, such as this example from Perleigh in Essex, dated 1782: "Amie Daughter of Moses Stebbing by a bought wife delivered to him in a Halter". A jury in Lincolnshire ruled in 1784 that a man who had sold his wife had no right to reclaim her from her purchaser, thus endorsing the validity of the transaction. In 1819 a magistrate who attempted to prevent a sale at Ashbourne, Derby, but was pelted and driven away by the crowd, later commented:

Although the real object of my sending the constables was to prevent the scandalous sale, the apparent motive was that of keeping the peace ... As to the act of selling itself, I do not think I have a right to prevent it, or even oppose any obstacle to it, because it rests upon a custom preserved by the people of which perhaps it would be dangerous to deprive them by any law for that purpose.

In some cases, such as that of Henry Cook in 1814, the Poor Law authorities forced the husband to sell his wife rather than have to maintain her and her child in the Effingham workhouse. She was taken to Croydon market and sold for one shilling, the parish paying for the cost of the journey and a "wedding dinner".

Venue

By choosing a market as the location for the sale, the couple ensured a large audience, which made their separation a widely witnessed fact. The use of the halter was symbolic; after the sale, it was handed to the purchaser as a signal that the transaction was concluded, and in some instances, those involved would often attempt further to legitimate the sale by forcing the winning bidder to sign a contract, recognising that the seller had no further liability for his wife. In 1735, a successful wife sale in St Clements was announced by the common cryer, who wandered the streets ensuring that local traders were aware of the former husband's intention not to honour "any debts she should contract". The same point was made in an advertisement placed in the Ipswich Journal in 1789: "no person or persons to intrust her with my name ... for she is no longer my right". Those involved in such sales sometimes attempted to legalise the transaction, as demonstrated by a bill of sale for a wife, preserved in the British Museum. The bill is contained in a petition presented to a Somerset Justice of the Peace in 1758, by a wife who about 18 months earlier had been sold by her husband for £6 6s "for the support of his extravagancy". The petition does not object to the sale, but complains that the husband returned three months later to demand more money from his wife and her new "husband".

In Sussex, inns and public houses were a regular venue for wife-selling, and alcohol often formed part of the payment. For example, when a man sold his wife at the Shoulder of Mutton and Cucumber in Yapton in 1898, the purchaser paid 7s. 6d. (£40 in 2021) and 1 imperial quart (1.1 l) of beer. A sale a century earlier in Brighton involved "eight pots of beer" and seven shillings (£30 in 2021); and in Ninfield in 1790, a man who swapped his wife at the village inn for half a pint of gin changed his mind and bought her back later.

Public wife sales were sometimes attended by huge crowds. An 1806 sale in Hull was postponed "owing to the crowd which such an extraordinary occurrence had gathered together", suggesting that wife sales were relatively rare events, and therefore popular. Estimates of the frequency of the ritual usually number about 300 between 1780 and 1850, relatively insignificant compared to the instances of desertion, which in the Victor

Pov Rus Hd Xxx

Porno Japanese And Black Cock

Melons Tube Xxx

Nice Ass Hd

Videos Pre Teens

Wife selling - Wikipedia

Wife selling (English custom) - Wikipedia

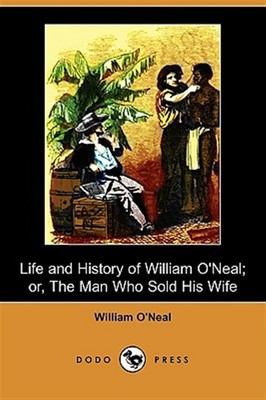

The Man Who Sold His Wife - On This Day

English Men Once Sold Their Wives Instead of Getting ...

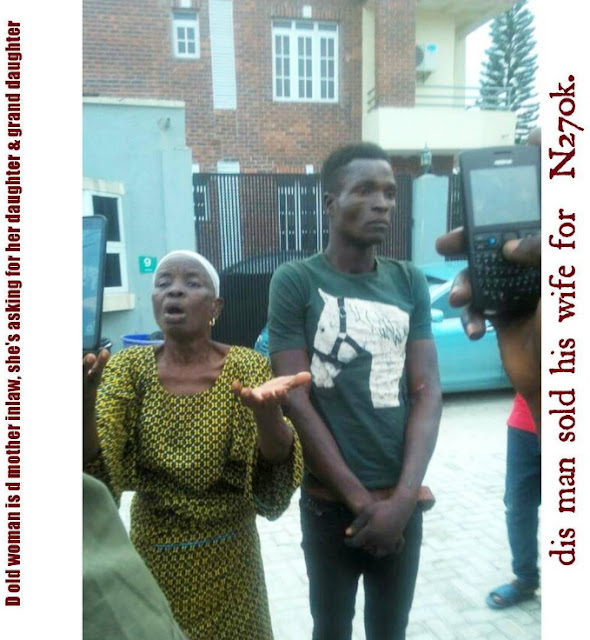

Husband Sold His Wife - YouTube

How to Sell Your Wife ... - #FolkloreThursday

A brief history of when men sold their wives at market ...

He Sold His Wife’s Pontiac to Buy This Dodge Charger ...

Sold His Wife