Singularities and Abstract Machines

Manuel De LandaExcerpt from Manuel De Landa's War In the Age of Intelligent Machines - Chapter One, Note 9

In this book I will use the blanket term "singularity" to refer to a variety of mathematical concepts. If the arguments that follow depended on finer distinctions, then a more detailed theory of the machinic phylum distinguishing between different kinds of mathematical singularities (bifurcations, attractors, repellors, etc.) would have to be employed. For those interested, the following is an explanation of some of the technical details involved in the mathematics of singularities.

To begin with, if computers can be used to explore the behavior of self-organizing processes (and of physical processes in general), it is because those processes may be modeled mathematically through a set of equations. Poincaré's discovered that if the workings of a given physical system may be so modeled, then they can also be given a visual representation called a "phase portrait." The creation and exploration of complex phase portraits, which in Poincaré's time was an almost impossible task, has today become feasible thanks to computers.

The first step in creating a phase portrait is to identify, in the physical system to be modeled, the relevant aspects of its behavior. It would be impossible, for example, to model a stove or an oven by considering each and every atom of which they are composed. Instead, we discard all irrelevant details, and consider the only aspect of the oven that matters: its temperature. Similarly, when modeling the behavior of the pendulum in a grandfather clock, all details may be left aside except for the velocity and position of the swinging pendulum. In technical terms, we say that the oven has "one degree of freedom": only its changes in temperature matter. The pendulum, in turn, has two degrees of freedom, changes in speed and position. If we wanted to model a bicycle, taking into account the coordinated motion of all its different parts (handlebar, front and back wheels, right and left pedals, etc.) we would end up with a system with approximately ten degrees of freedom.

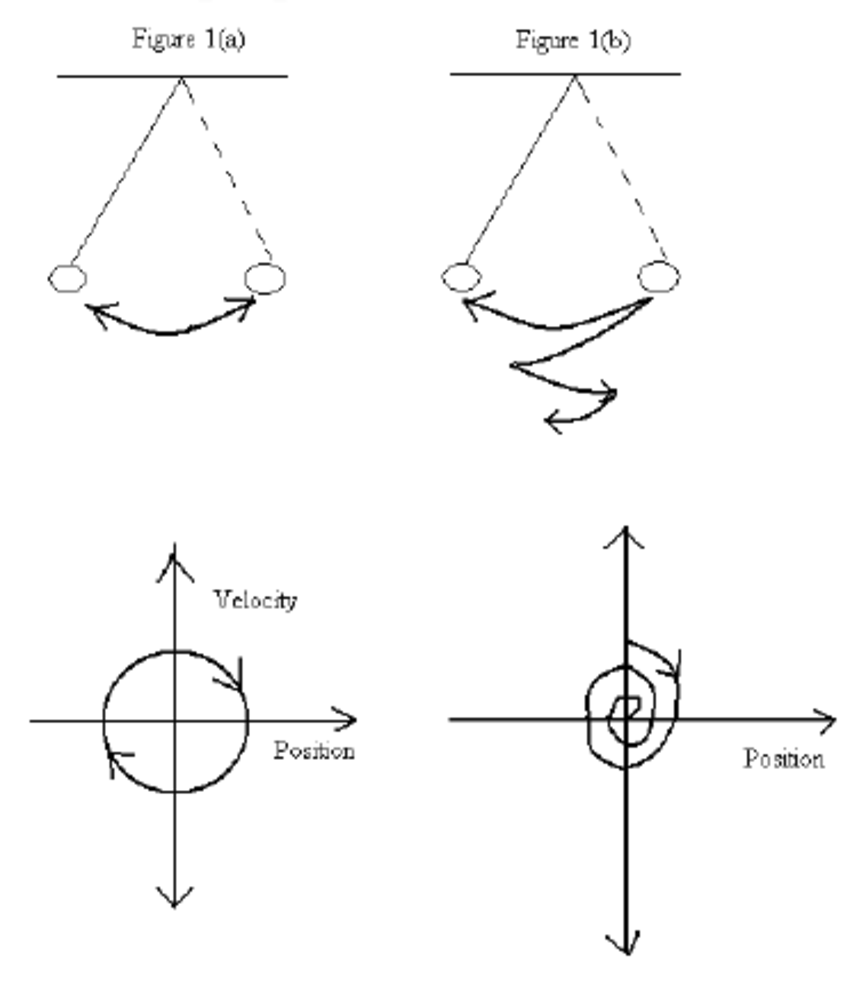

The idea behind a phase portrait is to create an abstract space with as many dimensions as degrees of freedom possessed by the object to be modeled. For the oven, a one-dimensional space (a line) would suffice. The pendulum would need a two dimensional space (a plane). A system with three degrees of freedom would involve a three-dimensional volume, and so on for more complex systems. In this phase space the state of the system at any given moment would appear as a point. That is, every thing that matters about the system at any particular moment may be condensed into a point: a point on a line for the oven, a point on a plane for the pendulum, a point in ten-dimensional space for the bicycle. The behavior of the system over time appears as the trajectory traced by that point as it moves in phase space. For example, if the system under study tends to oscillate between two extremes, like a driven pendulum, its trajectory in phase space will form a closed loop: a closed trajectory represents n system that goes through a series of states (the different positions of a pendulum) over and over again. A pendulum that is given a push and then allowed lo come to rest appears in phase portraits as a spiral, winding down us the pendulum comes to a rest. More complex systems will be represented by more complex trajectories in phase space.

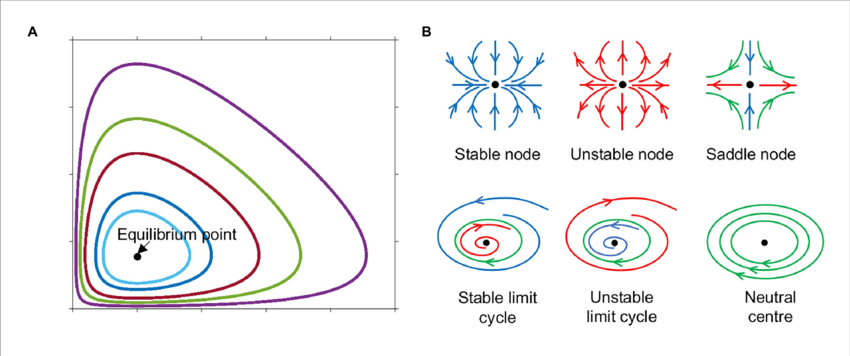

Now, it is one thing to model a system through a set of equations and completely different thing to solve those equations in order to make quantitative predictions about the system's future behavior. Sometimes, when the equations modeling a system are so complex that they cannot be used to learn about the system's behavior, scientists can still learn something by looking at its phase portrait: they cannot use it to make precise quantitative predictions about the system, but they can use it to elicit qualitative insights about the general traits governing the system's long-term tendencies. In particular, there are certain special spots in phase space that tend to attract (or repel) all nearby trajectories toward or away from them. That is, it does not matter where n trajectory begins, it will tend to drift toward certain points (called "attractors"), or move away from certain others (called "repellors").

Because these trajectories represent the behavior of real physical systems, the attractors and repellors in a phase portrait represent the long-term tendencies of a system, the kinds of behavior that the system will tend to adopt in the long run. For instance, a bull rolling downhill will always tend to "seek" the lowest point in the hill. If it is pushed up a little, it will roll down to this lowest point again. Its phase portrait will contain a "point attractor": small fluctuations (the ball being pushed up a little) will move the trajectory (representing the ball) away from the attractor, but then the trajectory will naturally return to it. To take a different example, we may have an electrical switch with two possible positions ("on" or "off'). If it is a good switch, it will always tend to be in either one of those positions. If small perturbations bring it to a third (intermediate) position it will naturally be attracted to return to one of its two points of equilibrium. In the case of the rolling ball, its tendency to seek the lowest point in the hill appears in it's phase portrait as a point attractor. Similarly, the phase portrait of the electrical switch will show two such point attractors, one for each stable state. We may learn a lot about a physical system (its long-term tendencies) simply by exploring the attractors in its phase portrait.

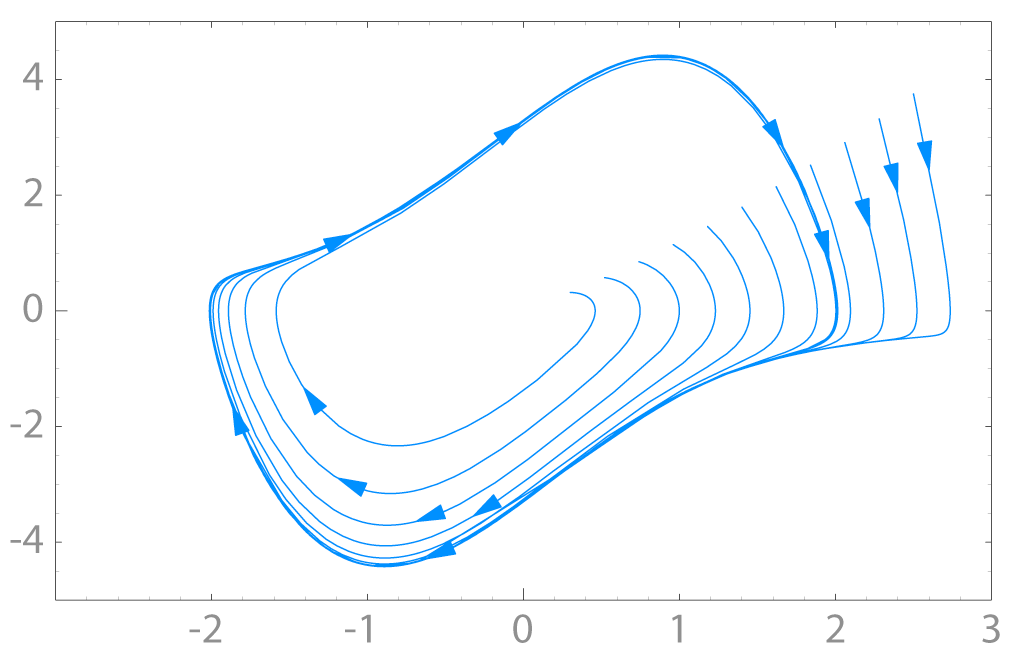

Attractors do not have to be points; they can also be lines. For instance, an attractor with the shape of a closed loop (culled a "periodic attractor" or "limit cycle") will force all trajectories passing near it to "wrap around it," that is, to enter into an oscillating state, like a pendulum. If the phase portrait of a given physical system has one of these attractors embedded in it, we know that no matter how we manipulate the behavior of the system, it will tend to return to an oscillation between two extremes. Even if we cannot predict exactly when the system will begin to oscillate (which would imply solving the complex equations modeling it), we know that sooner or later it will. Thus, a visual feature in these abstract landscapes (an attractor shaped like a closed loop), allows us to know the long-term tendencies of a given system's behavior, even before we actually trace its trajectory in phase space. It does not matter where the trajectory starts, it will inexorably be attracted toward that circular, singular trait of its phase portrait.

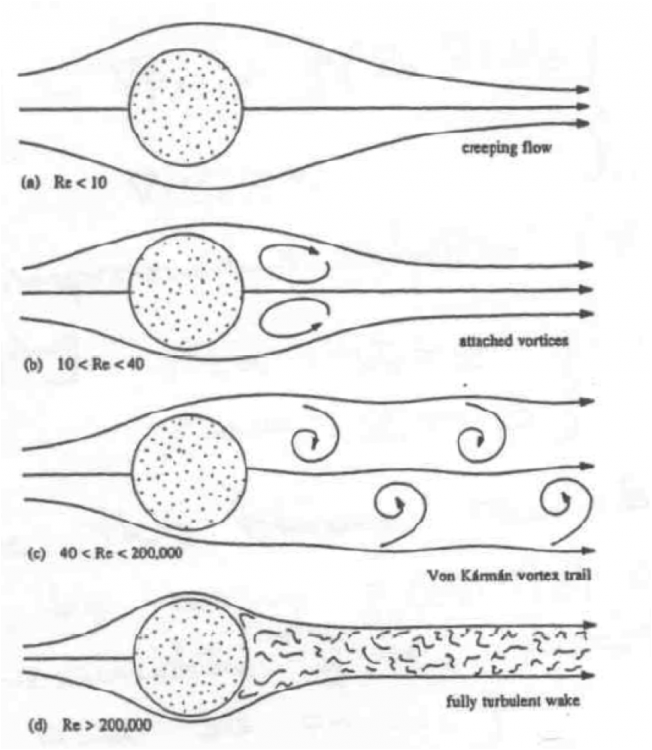

These two kinds of attractors (points and closed loops) were the only ones known prior to the digital age. But when computer screens became "windows" into phase space, it was discovered that this space was inhabited by a variety of much wilder creatures. In particular, attractors with strangely tangled shapes were discovered and called "strange" or "chaotic" attractors. They are now known to represent turbulent behavior in nature. Similarly, even when a phase portrait contains only simple attractors, the "basins of attraction" ( the area of phase space that constitutes an attractor's sphere of influence) may be separated by incredibly complex ("chaotic") boundaries. We do not yet know how to relate to these new creatures. In particular, we do not know if the term "chaotic" is appropriate since strange attractors are known to possess an intricate, fractal internal structure.

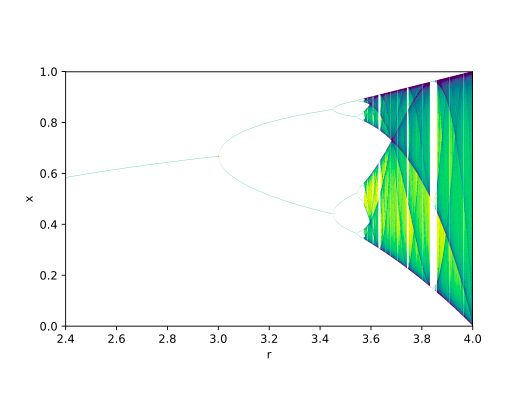

From the point of view of self-organization other features of phase space are more important than attractors. These are the so-called symmetry-breaking bifurcations. Bifurcations represent events in phase space in which one kind of attractor (say, a point) is transformed into another attractor (a circle, for instance). Such a bifurcation (from a point to a circle) would represent the fact that a physical system which originally tended to move toward a point of equilibrium had suddenly and spontaneously begun to oscillate between two extremes. This bifurcation would represent, for instance, the self-assembly of a chemical clock. To take a different example, the onset of turbulence in a flowing liquid (or the onset of coherence in laser light) appears in phase space as a cascade of bifurcations that takes the form of a circle (a limit cycle) and through successive doublings transforms it into a strange attractor. Roughly, we could say that phenomena of self-organization occur whenever a bifurcation takes pince: when a new attractor appears in the phase portrait of a system, or when the system's attractors mutate in kind.

Although the mathematical description of attractors and bifurcations is much more elaborate in detail, these few remarks will suffice for the purpose at hand: defining the concept of the "machinic phylum". To summarize this brief exposition, there are three distinct "entities" inhabiting phase space: specific trajectories, corresponding to objects in the actual world; attractors, corresponding to the long-term tendencies of those objects; and bifurcations, corresponding to spontaneous mutations of the long-term tendencies of those objects. In the late 1960s Gilles Deleuze realized the philosophical implications of these three levels of phase space. He emphasized the ontological difference between "actual physical systems" (represented by trajectories in phase space), and the "virtual physical systems" represented by attractors and repellors. Although he did not mention bifurcations by name, he explored the idea that special events could produce an "emission of singularities," that is, the sudden creation of a set of attractors and repellors.

In Deleuze's terminology a particular set of attractors and repellors constitute a "virtual" or "abstract" machine, while the specific trajectories in phase space represent "concrete incarnations" of that abstract machine. For example, a circular attractor represents an "abstract oscillator" which may be physically incarnated in many different forms: the pendulum in a clock, the vibrating strings of a guitar, and the oscillating crystals in radar and radio, digital watches, biological clocks. And just us one and the same attractor may be incarnated in different physical devices, one and the same bifurcation may be incarnated in different self-organizing processes: the onset of coherent behavior in a flowing liquid and the onset of coherent light emission in a laser are incarnations of the same bifurcation.

We have, then, two layers of "virtual machines": attractors and bifurcations. Attractors are virtual machines that, when incarnating, result in a concrete physical system. Bifurcations, on the other hand, incarnate by affecting the attractors themselves, and therefore result in a mutation in the physical system defined by those attractors. While the world of attractors defines the more or less stable and permanent features of reality (its long-term tendencies), the world of bifurcations represents the source of creativity and variability in nature. For this reason the process of incarnating bifurcations into attractors and these, in turn, into concrete physical systems, has been given the name of "stratification": the creation of the stable geological, chemical and organic strata that make up reality. Deleuze's theory attempts to discover one and the same principle behind the formation of nil strata. It is us if the lithosphere, the atmosphere and the biosphere were aspects of the same "mechanosphere." Or, alternatively, it is us if all the phylogenetic lineages produced by evolution (vertebrates, molluscs, but also clouds and rivers) were crossed by the same machinic phylum.

For a more detailed presentation of these ideas see: Manuel DeLanda, "Non-organic Life," Zone 6 (forthcoming). More details may be found in: Ian Stewart, Does God Play Dice? The Mathematics of Chaos (New York: Basil Blackwell, 1989); Ralph Abraham and Christopher Shaw, "Dynamics: The Geometry of Behavior," in The Visual Mathematics Library, 3 vols. (Santa Cruz, CA: Aerial Press).

For Deleuze's view on the ontological difference between the solutions of equations (trajectories in phase space) and the topological features of a vector field (attractors) see: Gilles Deleuze, Logic of Sense, tr. Mark York: Columbia University Press, Lester, ed. Constantin V. Boundas (New York: Columbia University Press 1990), ch. 15. Deleuze credits this insight into the idea of an ontological difference to Albert Lautman's Le Problem du temps.