Sell Your Wife

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

https://pranksters.com/sell-your-wife-joeysalads

Indecent Proposal: Would You Sell Your Wife For One Night?! You know the movie Indecent Proposal? It’s got Robert Redford in it as this suave old rich guy. He offers a fat stack of cash to regular Joe Woody Harrelson in return for one night with his wife (Demi Moore). It’s a moral dilemma….

https://folklorethursday.com/folklife/how-to-sell-your-wife

29.06.2017 · Some pertinent advice here. How do you rid yourself of a wife who no longer pleases you? Sell her, of course. The practice of a husband selling his wife …

How To Sell Your Wife On The New You

Would You Sell Your WIFE / GIRLFRIEND For a MERCEDES

Wife Leaves Husband After He Refuses to Sell Bitcoin...

Wife Sold For Money $100k ? (Social Experiment)

Water Garden: How to Sell your Wife.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wife_selling_(English_custom)

Ориентировочное время чтения: 9 мин

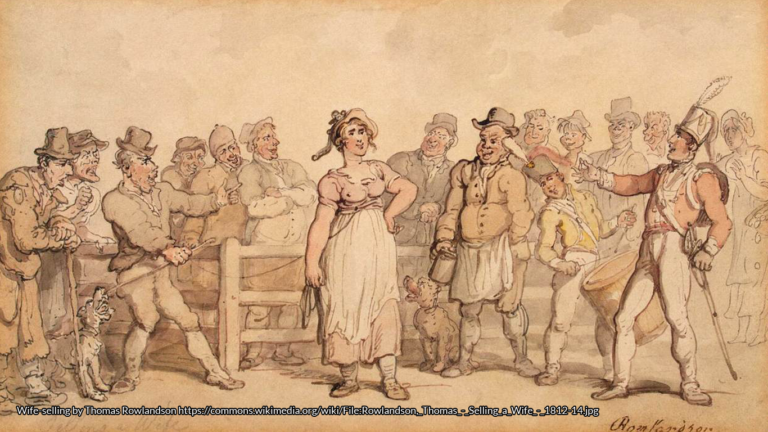

Wife selling in England was a way of ending an unsatisfactory marriage that probably began in the late 17th century, when divorce was a practical impossibility for all but the very wealthiest. After parading his wife with a halter around her neck, arm, or waist, a husband would publicly auction her to the highest bidder. Wife selling provides the backdrop for Thomas Hardy's 1886 novel The Mayor …

Wife selling in England was a way of ending an unsatisfactory marriage that probably began in the late 17th century, when divorce was a practical impossibility for all but the very wealthiest. After parading his wife with a halter around her neck, arm, or waist, a husband would publicly auction her to the highest bidder. Wife selling provides the backdrop for Thomas Hardy's 1886 novel The Mayor of Casterbridge, in which the central character sells his wife at the beginning of the story, an act that haunts him for the rest of his life, and ultimately destroys him.

Although the custom had no basis in law and frequently resulted in prosecution, particularly from the mid-19th century onwards, the attitude of the authorities was equivocal. At least one early 19th-century magistrate is on record as stating that he did not believe he had the right to prevent wife sales, and there were cases of local Poor Law Commissioners forcing husbands to sell their wives, rather than having to maintain the family in workhouses.

Wife selling persisted in England in some form until the early 20th century; according to the jurist and historian James Bryce, writing in 1901, wife sales were still occasionally taking place during his time. In one of the last reported instances of a wife sale in England, a woman giving evidence in a Leeds police court in 1913 claimed that she had been sold to one of her husband's workmates for £1.

What does it mean to sell your wife?

What does it mean to sell your wife?

Sell her, of course. The practice of a husband selling his wife in the open market with a rope around her neck so that she might be led away, as if she were no better than a piece of livestock, would seem to be a throw-back to an unpleasant aspect of medieval feudalism and women’s subservience to men.

folklorethursday.com/folklife/how-to-sell-yo…

Where did the practice of selling your wife take place?

Where did the practice of selling your wife take place?

This practice was still known in Hereford well into the 19th century. In 1802 a butcher sold his wife by public auction in Hereford market. The unfortunate woman – or perhaps she was fortunate in the change of circumstance – changed hands for one pound, four shillings, and a bowl of punch.

folklorethursday.com/folklife/how-to-sell-yo…

When was the first time someone sold their wife?

When was the first time someone sold their wife?

In 1802 a butcher sold his wife by public auction in Hereford market. The unfortunate woman – or perhaps she was fortunate in the change of circumstance – changed hands for one pound, four shillings, and a bowl of punch. In 1900, a woman of ninety years recalled, in a piece of oral history, having seen the sale of a wife on more than one occasion.

folklorethursday.com/folklife/how-to-sell-yo…

Не удается получить доступ к вашему текущему расположению. Для получения лучших результатов предоставьте Bing доступ к данным о расположении или введите расположение.

Не удается получить доступ к расположению вашего устройства. Для получения лучших результатов введите расположение.

This article is about the English custom. For related practices elsewhere, see Wife selling.

Wife selling in England was a way of ending an unsatisfactory marriage that probably began in the late 17th century, when divorce was a practical impossibility for all but the very wealthiest. After parading his wife with a halter around her neck, arm, or waist, a husband would publicly auction her to the highest bidder. Wife selling provides the backdrop for Thomas Hardy's 1886 novel The Mayor of Casterbridge, in which the central character sells his wife at the beginning of the story, an act that haunts him for the rest of his life, and ultimately destroys him.

Although the custom had no basis in law and frequently resulted in prosecution, particularly from the mid-19th century onwards, the attitude of the authorities was equivocal. At least one early 19th-century magistrate is on record as stating that he did not believe he had the right to prevent wife sales, and there were cases of local Poor Law Commissioners forcing husbands to sell their wives, rather than having to maintain the family in workhouses.

Wife selling persisted in England in some form until the early 20th century; according to the jurist and historian James Bryce, writing in 1901, wife sales were still occasionally taking place during his time. In one of the last reported instances of a wife sale in England, a woman giving evidence in a Leeds police court in 1913 claimed that she had been sold to one of her husband's workmates for £1.

Wife selling in its "ritual form" appears to be an "invented custom" that originated at about the end of the 17th century,[2] although there is an account from 1302 of someone who "granted his wife by deed to another man".[3] The practice was common enough in the 17th century for the English philosopher John Locke to write (apparently as a joke) in a letter to French scientist Nicolas Toinard [fr] that "Among other things I have ordered you a beautiful girl to be your wife [...] If you do not like her after you have experimented with her for a while you can sell her and I think at a better price than a man received for his wife last week in London where he sold her for four sous a pound; I think yours will bring 5 or 6s per pound because she is beautiful, young, and very tender and will fetch a good price in her condition."[4] With the rise in popularity of newspapers, reports of the practice become more frequent in the second half of the 18th century.[5] In the words of 20th-century writer Courtney Kenny, the ritual was "a custom rooted sufficiently deeply to show that it was of no recent origin".[6] Writing in 1901 on the subject of wife selling, James Bryce stated that there was "no trace at all in our [English] law of any such right",[7] but he also observed that "everybody has heard of the odd habit of selling a wife, which still occasionally recurs among the humbler classes in England".[8] It was often claimed to be common in rural England, but cleric and folkloricist Sabine Baring-Gould dedicated a whole chapter to it in his book on Devonshire folklore. As a child he witnessed the local poet return from market with a bought wife, and when confronted by the local justice of the peace and vicar (both related to Baring-Gould) he claimed the sale had been carried out correctly and that it was both legal and Christian.[9]

Until the passing of the Marriage Act of 1753, a formal ceremony of marriage before a clergyman was not a legal requirement in England, and marriages were unregistered. All that was required was for both parties to agree to the union, so long as each had reached the legal age of consent,[10] which was 12 for girls and 14 for boys.[11] Women were completely subordinated to their husbands after marriage, the husband and wife becoming one legal entity, a legal status known as coverture. As the eminent English judge Sir William Blackstone wrote in 1753: "the very being, or legal existence of the woman, is suspended during the marriage, or at least is consolidated and incorporated into that of her husband: under whose wing, protection and cover, she performs everything". Married women could not own property in their own right, and were indeed themselves the property of their husbands.[12] But Blackstone went on to observe that "even the disabilities the wife lies under are, for the most part, intended for her protection and benefit. So great a favourite is the female sex of the laws of England".[3]

Five distinct methods of breaking up a marriage existed in the early modern period of English history. One was to sue in the ecclesiastical courts for separation from bed and board (a mensa et thoro), on the grounds of adultery or life-threatening cruelty, but it did not allow a remarriage.[13] From the 1550s, until the Matrimonial Causes Act became law in 1857, divorce in England was only possible, if at all, by the complex and costly procedure of a private Act of Parliament.[14] Although the divorce courts set up in the wake of the 1857 Act made the procedure considerably cheaper, divorce remained prohibitively expensive for the poorer members of society.[15][a] An alternative was to obtain a "private separation", an agreement negotiated between both spouses, embodied in a deed of separation drawn up by a conveyancer. Desertion or elopement was also possible, whereby the wife was forced out of the family home, or the husband simply set up a new home with his mistress.[13] Finally, the less popular notion of wife selling was an alternative but illegitimate method of ending a marriage.[18] The Laws Respecting Women, As They Regard Their Natural Rights (1777) observed that, for the poor, wife selling was viewed as a "method of dissolving marriage", when "a husband and wife find themselves heartily tired of each other, and agree to part, if the man has a mind to authenticate the intended separation by making it a matter of public notoriety".[17]

Although some 19th-century wives objected, records of 18th-century women resisting their sales are non-existent. With no financial resources, and no skills on which to trade, for many women a sale was the only way out of an unhappy marriage.[19] Indeed, the wife is sometimes reported as having insisted on the sale. A wife sold in Wenlock Market for 2s 6d[b] in 1830 was quite determined that the transaction should go ahead, despite her husband's last-minute misgivings: "'e [the husband] turned shy, and tried to get out of the business, but Mattie mad' un stick to it. 'Er flipt her apern in 'er gude man's face, and said, 'Let be yer rogue. I wull be sold. I wants a change'."[20]

For the husband, the sale released him from his marital duties, including any financial responsibility for his wife.[19] For the purchaser, who was often the wife's lover, the transaction freed him from the threat of a legal action for criminal conversation, a claim by the husband for restitution of damage to his property, in this case his wife.[21]

The Duke of Chandos, while staying at a small country inn, saw the ostler beating his wife in a most cruel manner; he interfered and literally bought her for half a crown. She was a young and pretty woman; the Duke had her educated; and on the husband's death he married her. On her death-bed, she had her whole household assembled, told them her history, and drew from it a touching moral of reliance on Providence; as from the most wretched situation, she had been suddenly raised to one of the greatest prosperity; she entreated their forgiveness if at any time she had given needless offence, and then dismissed them with gifts; dying almost in the very act.[22]

It is unclear when the ritualised custom of selling a wife by public auction first began, but it seems likely to have been some time towards the end of the 17th century. In November 1692 "John, ye son of Nathan Whitehouse, of Tipton, sold his wife to Mr. Bracegirdle", although the manner of the sale is unrecorded. In 1696, Thomas Heath Maultster was fined for "cohabiteing in an unlawful manner with the wife of George ffuller of Chinner ... haueing bought her of her husband at 2d.q. the pound",[23] and ordered by the peculiar court at Thame to perform public penance, but between 1690 and 1750 only eight other cases are recorded in England.[24] In an Oxford case of 1789 wife selling is described as "the vulgar form of Divorce lately adopted", suggesting that even if it was by then established in some parts of the country it was only slowly spreading to others.[25] It persisted in some form until the early 20th century, although by then in "an advanced state of decomposition".[26]

In most reports the sale was announced in advance, perhaps by advertisement in a local newspaper. It usually took the form of an auction, often at a local market, to which the wife would be led by a halter (usually of rope but sometimes of ribbon)[6] around her neck, or arm.[27] Often the purchaser was arranged in advance, and the sale was a form of symbolic separation and remarriage, as in a case from Maidstone, where in January 1815 John Osborne planned to sell his wife at the local market. However, as no market was held that day, the sale took place instead at "the sign of 'The Coal-barge,' in Earl Street", where "in a very regular manner", his wife and child were sold for £1 to a man named William Serjeant. In July the same year a wife was brought to Smithfield market by coach, and sold for 50 guineas and a horse. Once the sale was complete, "the lady, with her new lord and master, mounted a handsome curricle which was in waiting for them, and drove off, seemingly nothing loath to go." At another sale in September 1815, at Staines market, "only three shillings and four pence were offered for the lot, no one choosing to contend with the bidder, for the fair object, whose merits could only be appreciated by those who knew them. This the purchaser could boast, from a long and intimate acquaintance."[28]

Although the initiative was usually the husband's, the wife had to agree to the sale. An 1824 report from Manchester says that "after several biddings she [the wife] was knocked down for 5s; but not liking the purchaser, she was put up again for 3s and a quart of ale".[29] Frequently the wife was already living with her new partner.[30] In one case in 1804 a London shopkeeper found his wife in bed with a stranger to him, who, following an altercation, offered to purchase the wife. The shopkeeper agreed, and in this instance the sale may have been an acceptable method of resolving the situation. However, the sale was sometimes spontaneous, and the wife could find herself the subject of bids from total strangers.[31] In March 1766, a carpenter from Southwark sold his wife "in a fit of conjugal indifference at the alehouse". Once sober, the man asked his wife to return, and after she refused he hanged himself. A domestic fight might sometimes precede the sale of a wife, but in most recorded cases the intent was to end a marriage in a way that gave it the legitimacy of a divorce.[32] In some cases the wife arranged for her own sale, and even provided the money for her agent to buy her out of her marriage, such as an 1822 case in Plymouth.[33]

Such "divorces" were not always permanent. In 1826 John Turton sold his wife Mary to William Kaye at Emley Cross for five shillings. But after Kaye's death she returned to her husband, and the couple remained together for the next 30 years.[34]

The French widely believed that it was common practice for a man tired of his wife to take her to London's Smithfield to be sold to the highest bidder, but cleric/historian challenged a French cleric who claimed he had read it from a reliable source. He then asked Baring Baring Gould if he knew of the practice, and was forced to admit he had witnessed the sale of the local poet as a child. Despite both the vicar and Justice of the Peace explaining the sale was not legal, the poet insisted it to be so, and they had a happy life together.[35]

Sales became more common in the mid 18th century, the result of husbands being abroad in the military, navy, or being transported to the colonies. It was commonly believed that an absence of 7 years constituted a divorce, so when the first husband returned to find his wife had a new family, the dilemma was solved by the first husband selling his wife in the market place for a nominal sum. It was not recognised as legal, as one wife had to wait for her first husband to die before being able to marry the father of her children. She was given away by her grandson.[36]

It was believed during the mid-19th century that wife selling was restricted to the lowest levels of labourers, especially to those living in remote rural areas, but an analysis of the occupations of husbands and purchasers reveals that the custom was strongest in "proto-industrial" communities. Of the 158 cases in which occupation can be established, the largest group (19) was involved in the livestock or transport trades, fourteen worked in the building trade, five were blacksmiths, four were chimney-sweeps, and two were described as gentlemen, suggesting that wife selling was not simply a peasant custom. The most high-profile case was that of Henry Brydges, 2nd Duke of Chandos, who is reported to have bought his second wife from an ostler in about 1740.[37]

Prices paid for wives varied considerably, from a high of £100 plus £25 each for her two children in a sale of 1865 (equivalent to about £14,400 in 2021)[38] to a low of a glass of ale, or even free. The lowest amount of money exchanged was three farthings (three-quarters of one penny), but the usual price seems to have been between 2s. 6d. and 5 shillings.[39] According to authors Wade Mansell and Belinda Meteyard, money seems usually to have been a secondary consideration;[5] the more important factor was that the sale was seen by many as legally binding, despite it having no basis in law. Some of the new couples bigamously married,[32] but the attitude of officialdom towards wife selling was equivocal.[5] Rural clergy and magistrates knew of the custom, but seemed uncertain of its legitimacy, or chose to turn a blind eye. Entries have been found in baptismal registers, such as this example from Perleigh in Essex, dated 1782: "Amie Daughter of Moses Stebbing by a bought wife delivered to him in a Halter".[40] A jury in Lincolnshire ruled in 1784 that a man who had sold his wife had no right to reclaim her from her purchaser, thus endorsing the validity of the transaction.[41] In 181

Dredd Up Your Ass

Latina Big Ass Porno Dh

Nude Mom Cam

Dad Fucks Daughter Porn Video

Naked Women With Nice Ass On Top

How to Sell Your Wife ... - #FolkloreThursday

Wife selling (English custom) - Wikipedia

Sell Your Wife

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/WEYJHXEIOJAMNHYMUIL6L5C2UI.JPG)