Scientific Articles On Special German Languages

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Entire website search

In category

Everywhere but category

Search

Filtered by type

Scientific articles

cancel filter

Статья. Опубликована в журнале "Das Wort. Germanistisches Jahrbuch Russland" — 2012/2013. — С. 95-107. Eine Fallstudie zur Auswirkung eines kurzfristigen Deutschlandaufenthaltes auf stereotype Vorstellungen russischer Studierender Содержание: Fragestellung Vorgang und Methodik Der Fall Svetlana: Ergebnisse der Fallanalyse Fazit Literatur

There are no files in this category.

German-language geography has a long and rich tradition, being credited with the conceptual foundation of human geography and major theoretical contributions in various areas of human geography research. In the wake of World War II, the discipline of geography had to reestablish itself in German-speaking countries, having suffered a loss of influence and international credibility. In recent years, however, German-language research in human geography has regained recognition. Today, it is characterized by a remarkable conceptual plurality and increasing diversity, which is at the heart of many critical debates within the German, Austrian, and Swiss scientific communities. While some commentators argue that this plurality is weakening the discipline in a changing university system and increasingly competitive institutional environment, where resources are fought over by various disciplines, others consider this diversity to be a strength that enables human geography to maintain its role in analyzing complex, real-world issues. Indeed, German-language geography has contributed much to empirical and applied research, both adding to the global knowledge base of human geography and benefiting secondary and higher education, nonacademic users, and policymakers in the German-speaking world.

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080449104002741

The drama of Peter and Héloïse was a prequel to twelfth century minstrelsy, comprising Provençal troubadours, German-language Minnesingers, French chansonniers, and other professional performers who traveled widely and enchanted their audiences with epic as well as mundane accounts of romantic love, resonances of which can be found in Orff's Carmina Burana – musical renditions of racy Medieval poems. Falling in love – what St Augustine deplored as a satanic snare to which he succumbed – was celebrated in the canzoni and epic poems that were composed and sung by these minstrels. These were arguably a powerful dynamic in shaping the individualism of that time. Two people who fall passionately in love find each other highly individualized to say the least. Lovers who only have eyes for one another do not regard their partners as fungible love objects.

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080970868250307

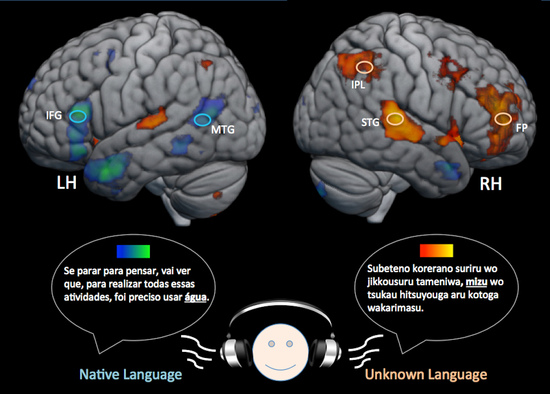

Much of destination language learning among immigrants comes from exposure to the destination language. Exposure can be thought of as having two dimensions—that is, exposure in the origin and exposure after migration.

The datasets used to study the determinants of immigrant's destination language skills generally indicate the country of origin, but provide no direct information on pre-immigration language learning.9 When conducting research on English-speaking destinations for immigrants from non-English-speaking origins, a proxy measure for pre-migration exposure to English is whether the origin was a former colony or dependency of either the UK or the US. Immigrants in the UK or the US from former colonies (e.g., Nigeria, India, or the Philippines) are found to be more proficient in English than are immigrants from other (non-English-speaking) countries that were not dependencies of the UK or the US (e.g., Thailand or Algeria), other variables being the same (Chiswick and Miller, 2001, 2007a). Similarly, immigrants in Spain from former colonies were reported by Isphording and Otten (2012) to be more proficient in Spanish than immigrants from other countries.

Another way of capturing pre-immigration exposure is to categorize countries according to whether the dominant language of the destination country is an official language or the dominant language of the country of origin, using sources such as the Ethnologue: Languages of the World (see Box 5.2). Espenshade and Fu (1997), for example, reported that the language spoken in the country of origin is an important determinant of English language skills among non-native English-speaking immigrants in the US. In analyses based on a binational source of data on Mexico–US migrants, Espinosa and Massey (1997) reported that the English proficiency is higher among migrants from communities (in Mexico) with greater proportions of adult men with US migrant experience, a variable which is argued to capture the “degree of contact with US culture within the respondent's community” (Espinosa and Massey, 1997, p. 37).

Thus, both the broad indicators provided by country of origin groupings, and the detailed information on origin country exposure where available, present a consistent set of evidence that pre-immigration exposure matters. Pre-immigration exposure has also been found to be an important determinant of proficiency in the dominant language of the destination country in the few studies that have been able to include direct measures. Raijman (2013), for example, studied the proficiency in Hebrew among Jewish South African immigrants in Israel, and reported that the level of Hebrew proficiency before arrival (typically acquired through attendance at Jewish schools and participation in synagogue activities and youth movements) was a highly significant and quantitatively important determinant of post-arrival proficiency.

The most important aspect of exposure to the destination language occurs after migration. Exposure in the destination can be decomposed into time units of exposure and the intensity of exposure per unit of time. Most data that identify the foreign-born members of the population ask the respondents when they came to the destination. From this, a variable for duration or “years since migration” can be computed. Duration has a very large positive and a highly statistically significant impact on destination language proficiency, but the effect is not linear. Rather, proficiency increases rapidly in the early years, but it increases at a decreasing rate; hence after a period of time a longer duration in the destination has a much smaller positive impact (Chiswick and Miller, 2001, 2007a, 2008b; Espenshade and Fu, 1997; Isphording and Otten, 2011, 2012). Grenier (1984) reported a similar pattern in his study of shifts from Spanish to English as the usual language among Hispanics in the US.

This time pattern for destination language proficiency is likely to be due to incentives for investment in language skills. For the following three reasons, an immigrant has the incentive to make greater investments shortly after arrival rather than delaying investments: to take advantage sooner of the benefits of increased proficiency, to make the investments when the value of the immigrants’ time (destination wage rate) is lower, and to have a longer expected future duration in the destination.

Duration may affect language proficiency because a longer actual duration increases the amount of exposure to and practice using the destination language. It is found that interrupted stays—that is, when immigrants move back and forth (sojourners)—reduce their language proficiency (Chiswick and Miller, 2001, 2007a, 2008b; Isphording and Otten, 2012). The expectation of an interrupted stay reduces the incentive to invest, implicitly if not explicitly, in language learning, and the destination language skills tend to depreciate during long periods of absence from the destination.

Moreover, those in the destination who report that they expect to return to their origin are also less proficient, other variables being the same (Chiswick and Miller, 2006). This might arise from negative selectivity in return migration, that those having a more difficult adjustment to the new country are more inclined to leave to return to the origin or to go to a third country. Or it might reflect the reduced incentive to invest in destination language skills if the expected future duration (i.e., the payoff period) is short.10

Espinosa and Massey (1997) were able to include very detailed information on individuals’ migration history in their study of Mexico–US migrants. Included are variables for the period of first entry, the period of last entry, the total time the individual had spent in the US since the first entry, the proportion of time spent in the US since the first entry, the average number of trips taken per year between the first and most recent visits, and the duration of the most recent trip. They report that English language skills increase with each of the latter four variables.

The intensity of exposure per unit of time in the destination is usually more difficult to measure. A few studies have included information on whether immigrants enrolled in formal classes of instruction in the destination language. Raijman (2013), for instance, related Hebrew proficiency of South African immigrants in Israel to whether they studied Hebrew in Israel for more than six months (i.e., through attending an uplan, which is an institute or school designed to teach adult immigrants basic Hebrew skills via an intensive course of instruction). Immigrants in this situation had higher levels of Hebrew proficiency than immigrants who studied for shorter periods or who did not enroll in a formal program of instruction in Hebrew. More often in the research, however, the focus is on the environment in which one lives, comprising both the area and the family. In terms of the area, it is useful to have a proxy measure of the ability to avoid using the destination language. Various measures have been used in the different studies, though the construct used most often is a “minority language concentration” measure. This is typically constructed as the percentage of the population, including the native-born and the foreign-born, in the area (defined by the state/province, region or metropolitan area) where the respondent lives, who speak the same non-destination language as the respondent. For example, the concentration measure for an Italian speaker living in Chicago would be the proportion of the population of Chicago who speak Italian. In other instances, newspapers (Australia) or radio broadcasting (US) in the language of origin have been used either as a substitute for, or in addition to, the minority language concentration measure.11 The effects on language proficiency of these area-based minority language concentration measures are quite strong. Destination language proficiency is significantly lower among individuals who have greater ease in avoiding using the destination language by living in a linguistic enclave area (Chiswick, 1998; Chiswick and Miller, 2007a, 2008b; Espenshade and Fu, 1997; Isphording and Otten, 2012; Lazear, 1999; Warman, 2007). Similarly, destination language use is less likely in areas with a geographical environment that favors interactions in the origin country language (Grenier, 1984). Where direct measures of social contact have been available (McAllister, 1986), such as the presence of “close friends from the country of origin”, the finding that such contacts reduce dominant language proficiency reinforces those based on the more general characteristics of the area of residence. Similarly, Espinosa and Massey (1997) report that English proficiency is higher among immigrants from Mexico in the US who have more extensive contacts with members of US racial and ethnic groups.

A key role in language learning is played by the family or household in the destination in which the immigrant lives. Both the spouse, if married, and the children matter. Those who married their current spouse before immigrating are likely to be married to someone with the same language background. They are more likely to speak that language to each other at home, thereby limiting opportunities for practicing the destination language at home.12 On the other hand, those who marry after immigration are more likely to marry someone proficient in the destination language, perhaps because of their own proficiency, and are more likely to practice the destination language. Where the data permit a study of this issue, it is found that, other measured variables being the same, the most proficient are those who married after migration, followed by those who are not married, with those who married their current spouse before migration being the least proficient (Chiswick and Miller, 2005b, 2007a, 2008b; Chiswick et al., 2005a, b; Dustmann, 1994). Grenier (1984) reported that, compared to the non-married, English language use at home was more likely among married Hispanics whose spouse was non-Hispanic, and less likely among Hispanics who were married to a Hispanic. The more direct evidence reported by Dustmann (1994) adds to this: based on analysis of immigrants in Germany, he reported that proficiency in German was higher where the partner has good German-speaking skills. Similarly, Espenshade and Fu (1997) showed that English skills are lowest where the spouse is from the same non-English language dominant country, and highest when the spouse is from any English language dominant country.

Children can have offsetting effects on their parents’ proficiency (Chiswick, 1998; Chiswick and Miller, 2007a, 2008b; Chiswick et al., 2005a, b). For example, children can serve wittingly, or unwittingly, as “teachers”. Whether they themselves are immigrants or not, children learn the destination language quickly because of their youth and because of their exposure to the destination language in school. They can, therefore, bring it home to their parents.

Yet, the presence of children can also have negative effects on their parents’ proficiency. Parents may speak the language of the origin at home to transmit the origin culture to their children, in part so that their children are able to communicate with the grandparents and other relatives who did not migrate or who migrated but lack proficiency in the destination language. Children may also serve as translators for immigrant parents. The translator role may be more effective in consumption activities and in dealings with the government bureaucracy and the educational and health care systems than in the workplace. Finally, children tend to reduce the labor supply of their mothers who stay at home to provide childcare. To the extent that adults invest in improving their language skills in anticipation of labor market activities, and benefit from doing so, and to the extent that practice using the destination language at work enhances proficiency, children would tend to be associated with lower proficiency among their mothers.

Taken as a whole, the four hypotheses regarding children suggest an ambiguous effect on their parents’ proficiency, but due to the latter two, their effect would be less positive or more negative for their mothers than their fathers. Empirically, this is in fact what is found. Where there is no clear effect of children on their father's proficiency, in the same data, it is less positive or more negative for their mothers (Chiswick and Miller, 2007a; Chiswick and Repetto, 2001; Chiswick, et al., 2005a, b; Grenier, 1984). Where there is a positive, albeit small, effect of children on their father's proficiency, the effect for mothers is statistically insignificant (Dustmann, 1994).

There is language learning in the home. Research has shown that the proficiency of one family member is positively associated with that of other family members (Chiswick et al., 2005b). The children's proficiency is more highly correlated with that of their mothers than with that of their fathers. This makes sense since mothers are generally more directly involved in the raising of their children than are the fathers. Similarly, Espinosa and Massey (1997) reported that the English proficiency of migrants from Mexico in the US was higher where they had siblings who were US migrants, and where they had children in US schools.

As a result, particularly due to a weaker attachment to the labor force, immigrant women with children have a lower level of destination language proficiency than do men and than do women without children (Chiswick et al., 2005a, b; Stevens, 1986).

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444537645000050

I next worked for the Swiss National Museum.5 During 2002–04, the project ‘Virtual Transfer Musée Suisse’ was produced as a new vision of interaction and communication with the museum visitors. All in all around 30 stories were being told, involving over 600 museum objects from eight different collections in five languages (German, French, Italian, Romansh and English). The artifacts, thus, become the narrators: the ‘chamber of marvels’, e.g., is divided into ‘masterpieces’, ‘favorite items’ and ‘curiosities’. By using the manifold capabilities of an artifact, a message can also be a political and critical statement, as was realised with the ‘Notzimmer’ (a set of knockdown furniture) of Mauritius Ehrlich, a social politician and Jew who fled from Vienna to Zurich after Richskristallnacht (Crystal Night) (see Fig. 32.4). I have used the Notzimmer as an example to develop a way for the deconstruction of complex hypermedia applications and published this analytical method in the museum journal Curator in January 2014.

Figure 32.4. Screenshot from Das Notzimmer des Mauritius Ehrlich (2002). Transfusionen for Swiss National Museum, Zurich (CD, Web).

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780081021453000327

The first newspaper published in the Czech language was Poštovské noviny (Post Office News) in 1719. The National Revival movement, which started after Joseph II's Patent of Toleration in 1781 and marked the relative freedom of the press under the enlightened rule of the Austro-Hungarian monarchs, saw the emergence of several new publications. After the establishment of the nationalist organization Czech Array in 1831, new titles such as Květy české (Czech Blossoms, 1834) were established by Czech patriots who wanted to improve the standard of Czech language and literature, but they ceased publication after a short time, as there were few subscribers and they did not make a profit. At the same time, German-language publications also persisted, especially in Moravia, including Mäehrisch-Slezische Zeitschrift (Moravian–Silesian Magazine).

Czech journalism came to flourish with the 1848 revolution when censorship was abolished and some 37 political newspapers and magazines were created, including Národní noviny (National News), Pražský posel (Prague Messenger), and Pokrok (Pr

Hard Ass Brazzers

Incest Taboo Full Movie

Free Voyeur Cams

Interracial Bisex Porno Film

Shows My Wifes Nude Pics To Friends

Scientific articles - German language - Languages and ...

German Language - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

German Linguistics - German Language Humanities - Research ...

The Language of (Future) Scientific Communication ...

Languages and language policies in Germany / Sprachen und ...

Languages | An Open Access Journal from MDPI

Languages: Why we must save dying tongues - BBC Future

Scientific Articles On Special German Languages