Scan HTML even faster with SIMD instructions (C++ and C#)

Daniel Lemire's blogEarlier this year, both major Web engines (WebKit/Safari and Chromium/Chrome/Edge/Brave) accelerated HTML parsing using SIMD instructions. These ‘SIMD’ instructions are special instructions that are present in all our processors that can process multiple bytes at once (e.g., 16 bytes).

The problem that WebKit and Chromium solve is to jump to the next target character as fast as possible: one of <, &, \r and \0. In C++, you can use std::find_first_of for this problem whereas in C#, you might use the SearchValues class. But we can do better with a bit of extra work.

The WebKit and Chromium engineers use vectorized classification (Langdale and Lemire, 2019): we load blocks of bytes and identify the characters you seek using a few instructions. Then we identify the first such character loaded, if any. If no target character is found, we just move forward and load another block of characters. I reviewed the new methods in C++ and C# in earlier posts along with minor optimizations. The results are good, and it suggests that WebKit and Chromium engineers were right to adopt this optimization.

But can we do better?

Let us consider an example to see how the WebKit/Chromium approach works. Suppose that my HTML file is as follows:

<!doctype html><html itemscope="" itemtype="http://schema.o'...

We load the first 16 bytes…

<!doctype html><

We find the target characters: the first character and the 16th character (<!doctype html><). We move to the first index. Later we start again from this point, this time loading slightly more data…

!doctype html><h

And this time, we will identify the 15th character as a target character, and move there.

Can you see why it is potentially wasteful? We have loaded the same data twice, and identified the same character twice as a target character.

Instead, we can use the approach used by systems like simdjson. We load non-overlapping blocks of 64 bytes. Each block of 64 bytes is turned into a 64-bit register where each bit in the word correspond to a loaded characters. If the character is a match, then the corresponding bit is set to 1. The computed 64-bit word acts like an index over the 64 characters and we can keep around or decode it at once. Once we have used it up, we can load another block and so forth.

Let us build a small C++ structure to solve this problem. We focus on ARM NEON, but the concept is general. ARM NEON is available on your mobile phone, on some servers and on your macBook.

Our constructor initializes the neon_match64 object with a character range defined by start and end. We define three public methods:

get(): Returns a pointer to the current position within the character range.consume(): Increments the offset and shifts thematchesvalue right by 1.advance(): Advances the position within the range

To iterate over the target characters, we might use it as follows:

neon_match64 m(start, end);

while (m.advance()) {

char * match = m.get(); m.consume();

}The class code might look like the following:

struct neon_match64 {

neon_match64(const char *start, const char *end)

: start(start), end(end), offset(0) {

low_nibble_mask = {0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0x26, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0x3c, 0xd, 0, 0};

bit_mask = {0x01, 0x02, 0x4, 0x8, 0x10, 0x20, 0x40, 0x80,

0x01, 0x02, 0x4, 0x8, 0x10, 0x20, 0x40, 0x80};

v0f = vmovq_n_u8(0xf);

update();

}

const char *get() const { return start + offset; }

void consume() {

offset++;

matches >>= 1;

}

bool advance() {

while (matches == 0) {

start += 64;

update();

}

int off = __builtin_ctzll(matches);

matches >>= off;

offset += off;

return true;

}

private:

inline void update() { update((const uint8_t*)start); }

inline void update(const uint8_t *buffer) {

uint8x16_t data1 = vld1q_u8(buffer);

uint8x16_t data2 = vld1q_u8(buffer + 16);

uint8x16_t data3 = vld1q_u8(buffer + 32);

uint8x16_t data4 = vld1q_u8(buffer + 48);

uint8x16_t lowpart1 = vqtbl1q_u8(low_nibble_mask,

vandq_u8(data1, v0f));

uint8x16_t lowpart2 = vqtbl1q_u8(low_nibble_mask,

vandq_u8(data2, v0f));

uint8x16_t lowpart3 = vqtbl1q_u8(low_nibble_mask,

vandq_u8(data3, v0f));

uint8x16_t lowpart4 = vqtbl1q_u8(low_nibble_mask,

vandq_u8(data4, v0f));

uint8x16_t matchesones1 = vceqq_u8(lowpart1, data1);

uint8x16_t matchesones4 = vceqq_u8(lowpart4, data4);

uint8x16_t sum0 =

vpaddq_u8(matchesones1 & bit_mask, matchesones2 & bit_mask);

uint8x16_t sum1 =

vpaddq_u8(matchesones3 & bit_mask, matchesones4 & bit_mask);

sum0 = vpaddq_u8(sum0, sum1);

sum0 = vpaddq_u8(sum0, sum0);

matches = vgetq_lane_u64(vreinterpretq_u64_u8(sum0), 0);

offset = 0;

}

const char *start;

const char *end;

size_t offset;

uint64_t matches{};

uint8x16_t low_nibble_mask;

uint8x16_t v0f;

uint8x16_t bit_mask;

};The most complicated function is the update function because ARM NEON makes it a bit difficult. We use use vld1q_u8(buffer) loads 16 bytes (128 bits) of data from the memory location pointed to by buffer into the data1 variable. Similarly, data2, data3, and data4 load subsequent 16-byte chunks from buffer + 16, buffer + 32, and buffer + 48, respectively. The expression vandq_u8(data1, v0f) performs a bitwise AND operation between data1 and a vector v0f (which contains the value 0xF in each lane). The expression vqtbl1q_u8(low_nibble_mask, ...) uses the low_nibble_mask vector to permute the low nibbles of the result of the AND operation. The result is stored in lowpart1, lowpart2, lowpart3, and lowpart4. The expressionvceqq_u8(lowpart1, data1): Compares each lane of lowpart1 with data1. If equal, the corresponding lane in the result is set to all ones (0xFF). They correspond to target characters. You repeat the same computation four times. We then use bitwise AND with bit_mask(...) followed by several applications of pairwise sums vpaddq_u8(...) to compute the 64-bit word.

I have added this C++ structure to an existing benchmark. Furthermore, I have ported it to C# for good measure.

How well does it do?

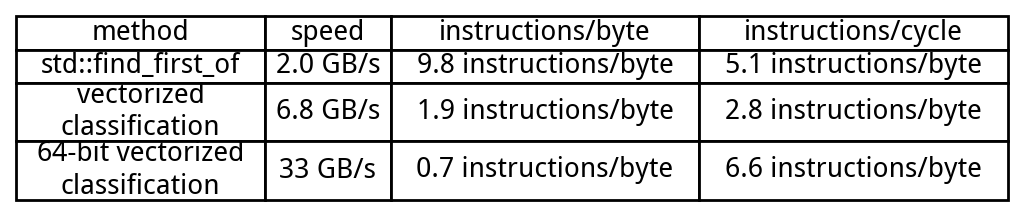

I use a C++ small benchmark where I scan the HTML of the Google home page. I run the benchmark on my Apple M2 laptop (LLVM 15).

The number speaks for themselves: the 64-bit vectorized classification approach is the clear winner. It requires few instructions and it allows retiring many instructions per cycle on average.

What about C#?

Again, the 64-bit vectorized-classification approach is the clear winner. The simdjson approach where we index non-overlaping 64-byte blocks seems quite applicable.

I have not yet ported the code for x64 processors, but I expect equally good results.

Generated by RSStT. The copyright belongs to the original author.