SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich - His private life & career

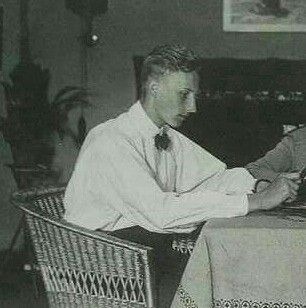

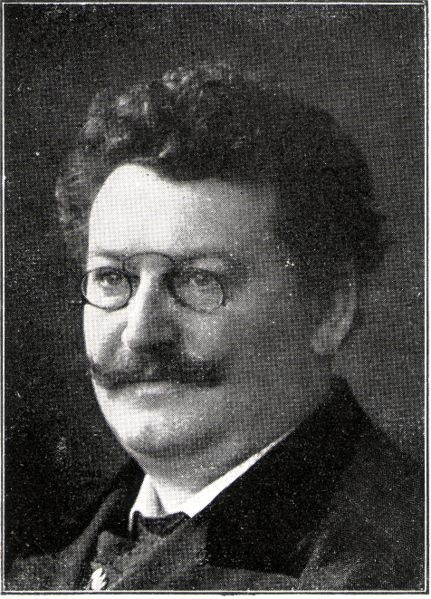

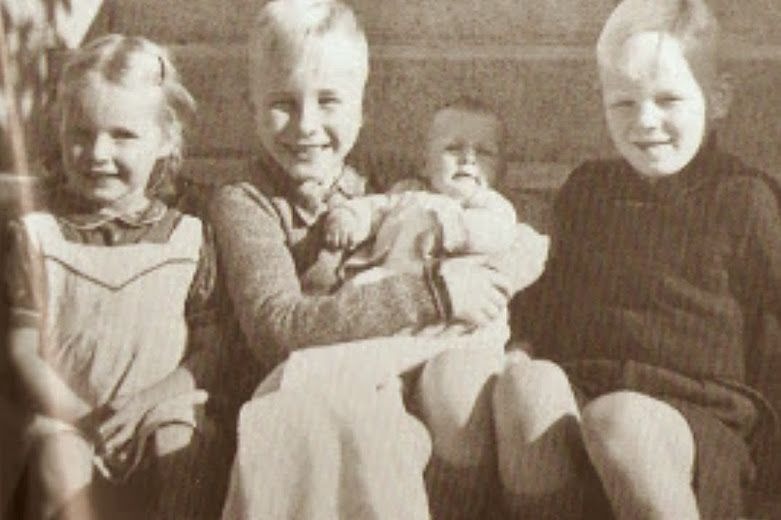

NS History LessonReinhard Heydrich was born the 7th March 1904 in Halle an der Saale, his parents were Elisabeth Krantz & Bruno Heydrich. His father founded a music school in 1899 which led to Reinhard learning to play the violin. A nationalist sentiment reigned in his childhood home, which was marked by Germany's defeat in World War 1 and the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

In 1919 he joined the Freikorps of Georg Märcker as a dispatch runner but never participated in any combat.

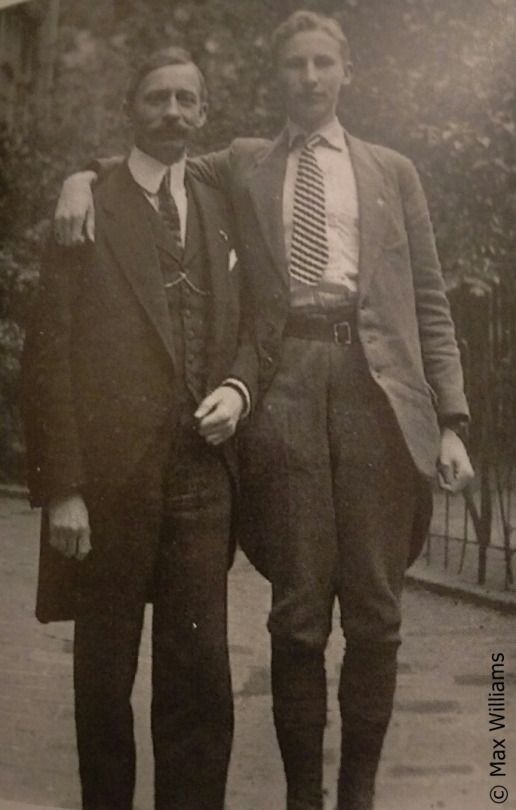

On 30th March 1922 he enlisted in the Reichsmarine (Imperial Navy) as a midshipman (Fahnrich). In 1926 he was commissioned an ensign (Leutnant zur See) and went through a training as a signals officer. He fulfilled this job until 1928 on the line ship "Schleswig-Holstein". On 1st July 1928 he was promoted to Oberleutnant zur See (highest rank of Lieutenant in the German Navy) and stationed at the Marinestation der Ostsee (Navy station of the East Sea) in Kiel.

In December 1930, Reinhard met Lina von Osten. They got engaged two weeks later after Reinhard asked permission to her father. She came out of a National Socialist family, her brother Hans von Osten joined the SA in 1928.

Prior to their engagement, Reinhard had a relationship with another lady (identity unknown to this day). He ended that relationship by sending an advertisement of his engagement. The father of this unknown lady made a formal complaint against Reinhard to Admiral Erich Raeder stating he promised to marry his daughter and breaking that promise was seen as disgraceful. After being court-martialled he was discharged the 30th April 1931 for conduct unbecoming to an officer and a gentleman.

Under the influence of Lina von Osten and her family, Reinhard joined the NSDAP the 1st June 1931, his membership number was 544916. One month later on 14th July he joined the SS and was given a commission as an SS-Untersturmführer (Second Lieutenant), his SS membership number was 10120. In August 1931 he was introduced to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler through a youth friend, the SA-Führer (SA leader) of Munich and SA-Brigadeführer of Oberbayern (Upper Bavaria) Friedrich Karl von Eberstein. In this meeting, Reinhard explained his vision of building up an intelligence service, this impressed the Reichsführer-SS and he was ordered to build up the organisation known as the Sicherheitsdienst or SD (security service). This would be the beginning of a close working relationship and friendship to Himmler. It would also be the beginning of a quick rising through the ranks of the SS. On the 1st December 1931 he was promoted to SS-Sturmhauptführer (prior to 1934, SS officer ranks were the same as the SA. This rank would eventually become Hauptsturmführer which is the equivalent to Captain). Just a few weeks later on 25th December he was again promoted to SS-Sturmbannführer (Major).

On the 26th December 1931 his marriage to Lina von Osten took place in Grossenbrode.

A next promotion on 29th July 1932 made him an SS-Standartenführer (Colonel) and was named "Chef des Sicherheitsdienstes beim Reichsführer-SS" (Chief of the security service).

After the Führer took power on 30th January 1933, the Reichsführer-SS was named police chief of Bavaria and Heydrich was given leadership of Abteilung VI (department 6) in the Munich Police Headquarters. This department was tasked with the monitoring of political activities and tracking of political offenses. A few weeks later this department was restructured as the Bayerische Politische Polizei or BPP (Bavarian political police). Himmler was named the leader of this police force but left the handling and leadership to Heydrich.

The concept and structure of this policeforce would be the base model for the development of the Sicherheitsdienst. This period would also give two promotions to Heydrich, namely the 21st March 1933 he was promoted to SS-Oberführer (Senior Colonel/Brigadier) and the 9th November 1933 he was promoted to SS-Brigadeführer (Brigadier General). His first son, Klaus was born on the 17th June 1933.

Heydrich became a member of the Prussian State Council on the 5th April 1934. On the 20th April 1934 Reichsmarschall Göring gave Himmler the leadership of the Preußischen Geheimen Staatspolizei (Prussian Secret Statepolice). The Reichsführer-SS named Heydrich "Chef des Geheimen Staatspolizeiamtes" (Chief of the Secret Police). With all these new functions, Heydrich moved his office from Munich to Berlin and just like he did with the Bavarian Political Police, he started to interlock SS and SD formations with the policeforces. This quick rise in power of the SS came together with a growing fear that the NS-leadership would lose control over the SA. It was reported that the SA and its leadership was increasingly dissatisfied. A group within the SA leadership felt it was them that brought the Führer to power and felt betrayed with their lesser role in the new state. This group eventually called for a second "socialist" revolution. This endangered the alliance that the Führer was building with the Reichswehr.

This would lead to the Night of the Long Knives in which Heydrich and his SD reported that a coup of the SA-leadership was imminent and action needed to be taken. From 30th June to 2nd July the SD together with the SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS death head units) arrested and executed most of the SA leadership.

These actions would lead to Heydrich's next promotion, on 30th June 1934 he was promoted to SS-Gruppenführer (Major General) which at the time was the second highest rank within the SS.

At the end of 1934, on the 23rd December his second son, Heider was born.

In 1936 the Reichsführer-SS Himmler was appointed Chief of the German Police which made Heydrich Chief of the Security Police (Sicherheitspolizei or SiPo). Heydrich was appointed to oversee the security at the 1936 Olympic Games.

The rising power of the SS became increasingly a thorn in the eye of the Wehrmacht who didn't want a second armed force in the Reich. This rivalry made the SS and SD take actions through targeted intrigues which removed the Commander in Chief of the army, General Werner von Fritsch and the War Minister Werner von Blomberg from their functions. This would solidify the control of the NS-state over the Wehrmacht.

The happenings of the Reichskristallnacht (9th November 1938), surprised both Himmler and Heydrich because it was ordered mainly out of the office of Dr. Joseph Goebbels. On the aftermath in the morning of 10th November 1938 orders were sent out to arrest in all districts as many jews possible that could fit in the existing prison facilities.

Heydrich's third child, a daughter named Silke was born on 9th April 1939.

With the invasion of Poland starting the 1st September 1939, Reinhard served as a reserve Hauptmann (captain) in the Luftwaffe (Airforce) as a turret gunner in the Kampfgeschwader 55 (Battle squadron).

On the 27th september 1939, the Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA (Reich Security Headquarters) was created. Heydrich would lead this office and insert his SD and Security policeforces as part of this new establishment. Another unit that part of the RSHA were the Einsatzgruppen (task forces). These task forces would be deployed behind the advancing German troops to root out any partisan resistance from jewish or political enemies of the Reich.

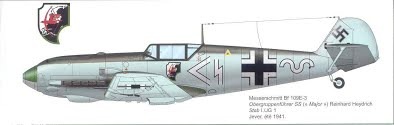

By 1940 Reinhard completed a fighter pilot course because he wanted to set an example and show that the SS were not "asphalt" soldiers but the elite of the Reich. He would fly with the Jagdgeschwader 77 (fighter squadron) in the battle of Norway. The plane with which he flew was a Messerschmidt Bf 109E-7. The plane flown by Heydrich had a Germanic Sig rune painted on the fuselage. For a short time in May 1940 he would fly patrol flights above Northern Germany and the Netherlands. On the 13th May 1940 he crashed his plane during take-off and was injured. Then after another accident he returned to Berlin.

In the summer of 1941 he disregarded an explicit order of the Reichsführer-SS not to participate in combat missions and reported for duty at the airport of Bălți, Romania in the Southern section of the Eastern Front. He wore the uniform of a Luftwaffe Major and was assigned to the 2nd group of the Jagdgeschwader 77.

His plane was damaged on the 22nd July above Jampol by Soviet anti-aircraft fire. He had to perform an emergency landing in no-man's land. He luckily evaded a Soviet patrol and was able to make his way back to German lines. After this, he was forbidden to fly in combat, as it was realized that his capture as a prisoner of war would be a major security breach for Germany. He never flew another operational sortie.

Heydrich was decorated with the Iron Cross Second (1940) and First (1941) Classes. The number of missions he flew is not known, but he was awarded the Frontflugspange (Front Pilot Badge) in silver, which usually was awarded after 60 combat missions.

On 27 September 1941, Heydrich was promoted to SS-Obergruppenführer and was appointed Deputy Reich Protector of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (the part of Czechoslovakia incorporated into the Reich on 15 March 1939) and assumed control of the territory. The Reich Protector, Konstantin von Neurath, remained the territory's titular head, but was sent on "leave" because Hitler, Himmler, and Heydrich felt his "soft approach" to the Czechs had promoted anti-German sentiment and encouraged anti-German resistance via strikes and sabotage.

Heydrich came to Prague to enforce policy, fight resistance to the Nazi regime, and keep up production quotas of Czech motors and arms that were extremely important to the German war effort.

Heydrich started his rule by proclaiming martial law, and 142 people were executed within five days of his arrival in Prague. Their names appeared on posters throughout the occupied country. Most of them were the members of the resistance that had previously been captured and were awaiting trial.

According to Heydrich's estimate, between 4,000 and 5,000 people were arrested and between 400 and 500 were executed by February 1942. Those who were not executed were sent to Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp. Czech Prime Minister Eliáš was among those arrested the first day. He was put on trial in Berlin and sentenced to death, but was kept alive as a hostage. He was later executed in retaliation for Heydrich's assassination. Labor was reorganised on the basis of the German Labour Front. Heydrich used equipment confiscated from the Czech gymnastics organisation Sokol to organise events for workers. Food rations and free shoes were distributed, pensions were increased, and free Saturdays were introduced. Unemployment insurance was established for the first time. The black market was suppressed. Those associated with the resistance movement were arrested or executed. Heydrich also decided that a new concentration camp should be built in Theresienstadt for the jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia.

By 3 October 1941, Czechoslovak military intelligence in London had made the decision to kill Heydrich.

Jan Kubiš and Jozef Gabčík headed the team chosen for the operation, trained by the British Special Operations Executive. They returned to the Protectorate, parachuting from a plane on 28 December 1941, where they lived in hiding, preparing for the mission.

On 27 May 1942, Heydrich planned to meet Hitler in Berlin. German documents suggest that Hitler intended to transfer him to German-occupied France where the French resistance was gaining ground. Heydrich would have to pass a section where the Dresden-Prague road merges with a road to the Troja Bridge. The junction in the Prague suburb of Libeň was well suited for the attack because motorists have to slow for a hairpin bend. As Heydrich's car slowed, Gabčík took aim with a Sten submachine gun, but it jammed and failed to fire. Heydrich ordered his driver, Klein, to halt and attempted to confront Gabčík rather than speed away. Kubiš, who wasn't spotted by Heydrich or Klein, threw a converted anti-tank mine at the car as it stopped, landing against the rear wheel. The explosion ripped through the right rear fender and wounded Heydrich, with metal fragments and fibres from the upholstery causing serious damage to his left side. He suffered major injuries to his diaphragm, spleen, and one lung, as well as a broken rib. Kubiš received a minor shrapnel wound to his face. After Kubiš fled, Heydrich ordered Klein to chase Gabčík on foot, and Gabčík shot Klein in the leg, before escaping himself.

A Czech woman went to Heydrich's aid and flagged down a delivery van. He was placed on his stomach in the back of the van and taken to the emergency room at Bulovka Hospital. A splenectomy was performed, and the chest wound, left lung, and diaphragm were all debrided. Himmler ordered Karl Gebhardt to fly to Prague to assume care. Despite a fever, Heydrich's recovery appeared to progress well. Hitler's personal doctor Theodor Morell suggested the use of the new antibacterial drug sulfonamide, but Gebhardt thought that Heydrich would recover and declined the suggestion. Heydrich reconciled himself to his fate on 2 June, during a visit by Himmler.

Heydrich fell into a coma on 3 June, the day after Himmler's visit, and never regained consciousness. He died on 4 June at 4:30h ; an autopsy concluded that he died of sepsis. He was 38 years old.

After an elaborate funeral held in Prague on 7 June 1942, Heydrich's coffin was placed on a train to Berlin, where a second ceremony was held in the new Reich Chancellery on 9 June. The Reichsführer-SS gave the eulogy. The Führer attended and placed Heydrich's decorations—including the highest grade of the German Order, the Blood Order Medal, the Wound Badge in Gold, and the War Merit Cross 1st Class with Swords—on his funeral pillow.

Heydrich was interred in Berlin's Invalidenfriedhof, a military cemetery. A photograph of Heydrich's burial shows the wreaths and mourners to be in section A, which abuts the north wall of the Invalidenfriedhof and Scharnhorststraße, at the front of the cemetery. A recent biography of Heydrich also places the grave in Section A. The Führer planned for Heydrich to have a monumental tomb (designed by sculptor Arno Breker and architect Wilhelm Kreis) but, due to Germany's declining fortunes, it was never built.

His second daughter, Marte was born after his death on 23rd July 1942.

His first son, Klaus would die soon after him in a traffic accident on 24th October 1943.

A list of Reinhard Heydrich's awards and decorations:

German Order (Posthumous)

Blood Order (Posthumous)

War Merit Cross 1st Class with Swords (Posthumous)

Wound Badge in Gold (Posthumous)

Golden Party Badge

Iron Cross Second (1940) and First (1941) Classes

Luftwaffe Pilot's Badge (Flugzeugführerabzeichen)

Combatclasp for Reconnaissance (Frontflugspange für Aufklärer) in Bronze (1940) and in Silver (1941)

Danzig Cross First Class (1939)

Anschluss Medal (1938)

Sudetenland Medal with Prague Castle Bar (1938)

Memel Medal (1939)

West Wall Medal (1940)

Olympic Games Decoration First Class (1936)

Social Welfare Decoration First Class

NSDAP Long Service Award in Bronze For 10 Years Service

Police Long Service Award Second Class For 18 Years Service

SS-Honour Ring

Honour Sword of the Reichsführers-SS

Honour Chevron for the Old Guard

German Sports Badge in Silver

German Equestrian Badge in Silver

SA Sports Badge in Gold

SS Long Service Award For 12 Years Service

Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus: Commander (1937) and Grand Officer

Order of the Crown of Italy: Grand Officer (1937) and Knight of the Grand Cross (1938)

A Letter from:

Lina Heydrich to Jean Vaughan, December 12, 1951

TODAY I am going to tell you something about the character of my husband.

The most characteristic trait was that he was a man of few words. He never talked about something or discussed something [just] for the love of talk. Every word had to have a concrete meaning, or purpose, had to hit the point. Therefore he never said even one word more than necessary.

He did not read much. Never did he read novels or philosophical books, eventually he read themes on scientific topics.

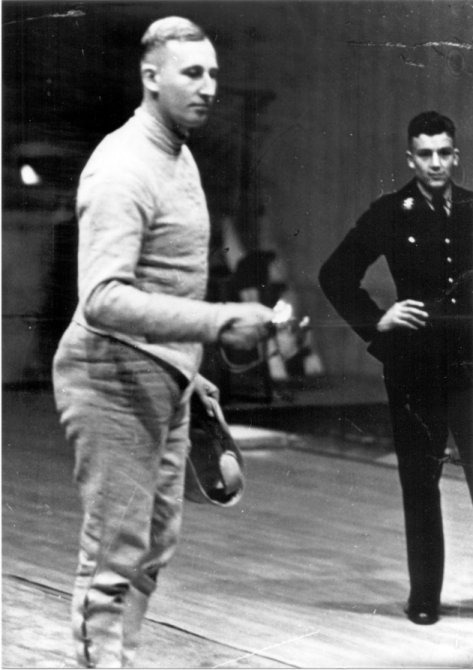

He never wasted a minute of his time. Every minute had to have is aim and purpose. Therefore he simply hated to go for a walk. Gymnastic exercise was not meant for a past-time or leisure, but for discipline, a training to reach the highest possible record in it. Therefore he always chose such sports to which he did not take naturally, but which required a hard training, self discipline. For instance, he was not at all gifted for fencing, but the end of its hard and enduring training was that he became German champion.

The only exception in this respect was perhaps hunting. But even that was not only and simply pleasure and past-time. He knew he had to get away from his office, his work, once [in] a while, that he had to relax; and going hunting meant recreation and activity at the same time.

In the morning, while being shaved, he worked at the new reports that had come in during the night (we call that "Akten," I don't know whether the correct English expression wants perhaps be "file"). After breakfast during the 30 minutes ride to the office this reading was continued. He never let his staff had even a minute's rest, it was very hard and strenuous for them.

During lunch … conferences. Lunch was taken in a small dining room in the office. Very often people who had to report on something were ordered to take part in this luncheons. But woe betide him who tried to begin a "speech." His own way of expression was the condensed and abbreviated style of telegrams (wires) and in this language he expected the reports, bare of every unnecessary word. If some one did not know that, he was sure to be interrupted after a few minutes by the words, "der langen Rede kurzer Sinn ist --" i.e., "that's what you wanted to say, was it not?" (I think the first words of this has been translated into 'the final analysis is..') [i.e., cutting to the bottom line].

My husband never had time. He had lost the human measure. He always hurried his subordinates. He did not know any private or family life, and he did not estimate that of his fellow-workers. His life was the conditionless [unconditional] devotion to his task and that was what he expected from everyone. Once a newly engaged assistant asked quite harmless[ly] what his wages would be. "Wages," my husband asked him. "You ought to ask what your work is going to be. Until now nobody is starved in my ressort."

Money did not mean a thing to my husband. He only knew that you could not live without it. Some one in the office was in charge of his money. He had to meet all the expenses and he talked with me about them eventually. My husband said, "An old stocking is of more value than 10 Reichsmarks, for I cannot put on and wear a stocking, ten marks don't keep me warm." At the time when I heard him say that I laughed, but now I understand him quite well.

My husband was vain. He hated nothing more than to be dressed inadequately. That did not apply to his wife. She might have worn the most impossible dresses, he thought them all right.

He also was ambitious, ambition meant work and efficiency, it meant "don't seem to be more than you are." The fact that he spoke so little made him seem a ruffian, but his refined and exquisite manners charmed every one.

He could deliver speeches or orations, but he could take part in discussions and then his logic was forceful. Once when he explained to Himmler the nonsense of one of Himmler's speeches, Himmler said to him: "You, with your damned logic!"

His memory was astounding. He never needed a telephone directory. He knew by heart all the numbers he needed, he never forgot a single report that he had read. In this respect the most surprising stories are told about him.

Neither in his youth nor later on had he any personal friends. He also tried to avoid every social contact with neighbors or fellow workers. That was very hard on me. When I once asked him for the reason, he answered, "How can I be friends with any one, as I never can tell whether there might not perhaps arise the possibility of having him arrested one day!"

He distrusted every one and he was hardly ever mistaken in his judgment of persons. How often did he not say to me, "I don't know, there is something about this person that I don't like, if I would only know what's wrong with him." So my husband who seemed to be guided only by his logic and intelligence was in the end led by intuition. There was an immense danger in his development, that of human isolation.

He was easily irritated and got excited about the smallest matters such as wrongly filed reports, incorrectness in the behavior of adjutants, belated beginnings of public assemblies, and so on. But difficult problems in his work he solved without any signs of excitement. He was the man who passed the most dangerous cliff without difficulty, but whom a straw caused to stumble.

He required absolute obedience as he himself obeyed without questioning. Order was order, and a soldier had to have no personal opinion as to an order.

His way of living (standard of life?) was modest. He did not like pomp, nor to be the centre of a society. He loved good food, but he did not like splendid dinners. Receptions, state funerals, public affairs of every kind he just hated, and he tried to get away from them wherever he could. He smoked little and hardly ever took alcohol. When he did go out, he preferred to go incognito. His daily life was scheduled to the minute. He kept absolute silence as to office matters.

He never gave in before he had reached the aim he wanted to reach. If he did once mistrust a person, it was exceedingly difficult to convince him or to prove to him that this person did not earn [deserve] this judgment.

He was not at all conciliate [sic. conciliatory?] nor did he flatter. Therefore he thought it convenient to have a superior like Himmler, who took over all that he himself did not like. He saw quite well that Himmler cut a rather poor figure in social affairs, but as long as he himself did not need appear in public he did not mind.

As to all the funny ideas of Himmler, his tendency to mysticism, his pride of being a soldier, my husband just had a well-meaning smile for them. But when there were differences of opinion concerning official matters my husband stood his ground unshakably.

Orders from Hitler were obeyed absolutely. My husband saw in him the one great man. I sometimes ask myself what his thoughts would have been if he had seen the bitter end. He thought him to be the one and only being who could lead the German nation to greatness and glory. Therefore it is good that my husband died in 1942. He has kept hisHis memory was astounding. He never needed a telephone directory. He knew by heart all the numbers he needed, he never forgot a single report that he had read. In this respect the most surprising stories are told about him.

Neither in his youth nor later on had he any personal friends. He also tried to avoid every social contact with neighbors or fellow workers. That was very hard on me. When I once asked him for the reason, he answered, "How can I be friends with any one, as I never can tell whether there might not perhaps arise the possibility of having him arrested one day!"

He distrusted every one and he was hardly ever mistaken in his judgment of persons. How often did he not say to me, "I don't know, there is something about this person that I don't like, if I would only know what's wrong with him." So my husband who seemed to be guided only by his logic and intelligence was in the end led by intuition. There was an immense danger in his development, that of human isolation.

He was easily irritated and got excited about the smallest matters such as wrongly filed reports, incorrectness in the behavior of adjutants, belated beginnings of public assemblies, and so on. But difficult problems in his work he solved without any signs of excitement. He was the man who passed the most dangerous cliff without difficulty, but whom a straw caused to stumble.

He required absolute obedience as he himself obeyed without questioning. Order was order, and a soldier had to have no personal opinion as to an order.

His way of living (standard of life?) was modest. He did not like pomp, nor to be the centre of a society. He loved good food, but he did not like splendid dinners. Receptions, state funerals, public affairs of every kind he just hated, and he tried to get away from them wherever he could. He smoked little and hardly ever took alcohol. When he did go out, he preferred to go incognito. His daily life was scheduled to the minute. He kept absolute silence as to office matters.

He never gave in before he had reached the aim he wanted to reach. If he did once mistrust a person, it was exceedingly difficult to convince him or to prove to him that this person did not earn [deserve] this judgment.

He was not at all conciliate [sic. conciliatory?] nor did he flatter. Therefore he thought it convenient to have a superior like Himmler, who took over all that he himself did not like. He saw quite well that Himmler cut a rather poor figure in social affairs, but as long as he himself did not need appear in public he did not mind.

As to all the funny ideas of Himmler, his tendency to mysticism, his pride of being a soldier, my husband just had a well-meaning smile for them. But when there were differences of opinion concerning official matters my husband stood his ground unshakably.

Orders from Hitler were obeyed absolutely. My husband saw in him the one great man. I sometimes ask myself what his thoughts would have been if he had seen the bitter end. He thought him to be the one and only being who could lead the German nation to greatness and glory. Therefore it is good that my husband died in 1942. He has kept his faith and ideal.

I wrote you these items today because they just came to my mind. I am not always able to write, there are too hard and woeful memories connected with this.

Gez. [signed] L H