Roman War Prisoner Art

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

https://paintingvalley.com/roman-warrior-painting

Перевести · All the best Roman Warrior Painting 34+ collected on this page. Feel free to explore, study and enjoy …

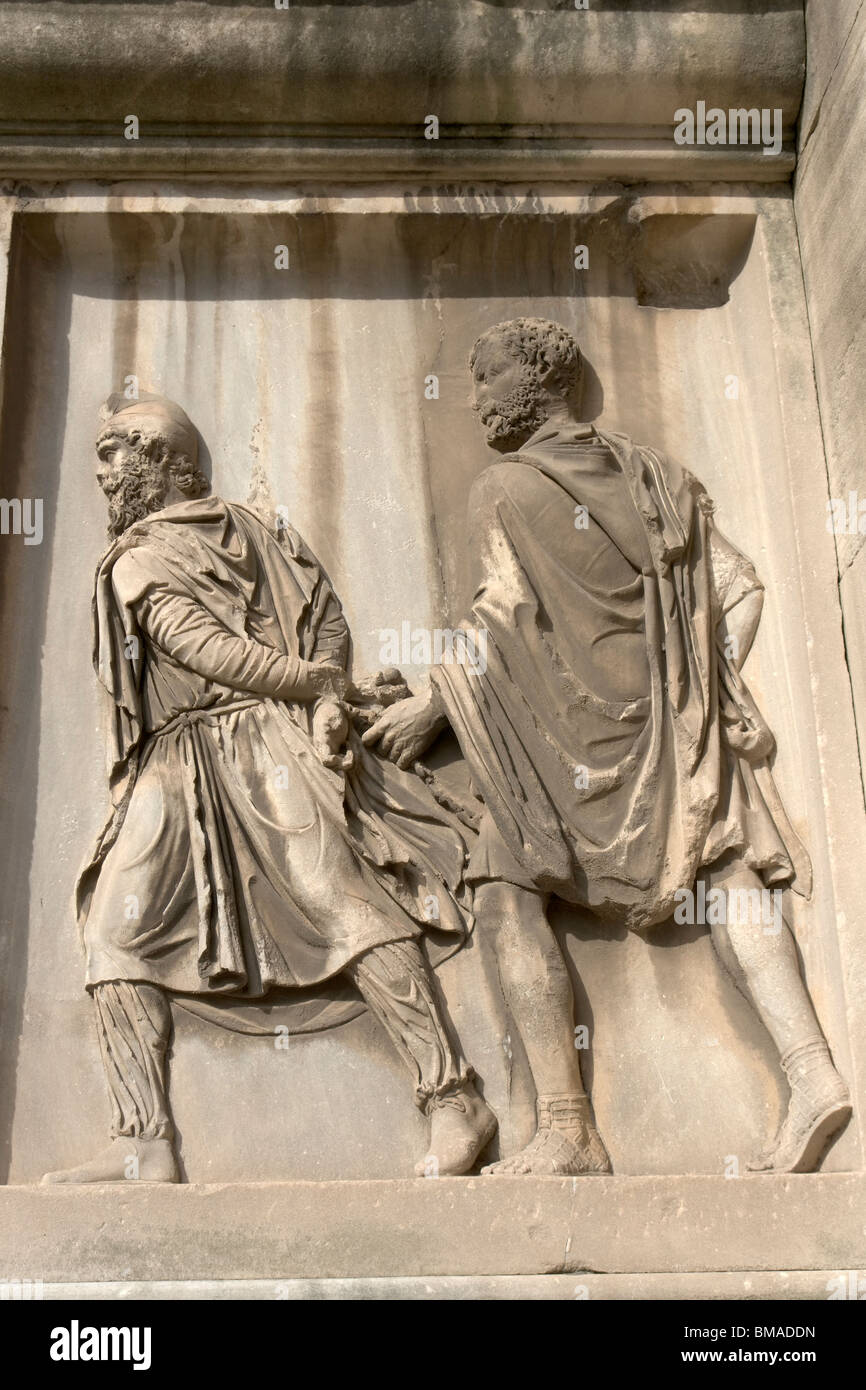

https://www.meisterdrucke.uk/fine-art-prints/Roman-Roman/982082/Roman-art:-“a-dace...

Перевести · Buy Roman art: “a dace soldier prisoner of Roman soldiers” Mould of 1862 reproducing the bas-reliefs of the column of Trajan (column Trajane) (Colonna Traiana) in Rome built during the reign of Emperor Trajan (53-117). The Trajane column commemorates the v by Roman Roman as fine art …

www.digitalattic.org/home/war/romanarmy

Перевести · The systematic investment and siege of fortified places was an important and well-studied feature of the Roman military art and gave them an …

https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/portchester-castle-from-roman-fort-to...

Перевести · Art movements; Historical events; Historical figures; Places; About; View activity; Send feedback

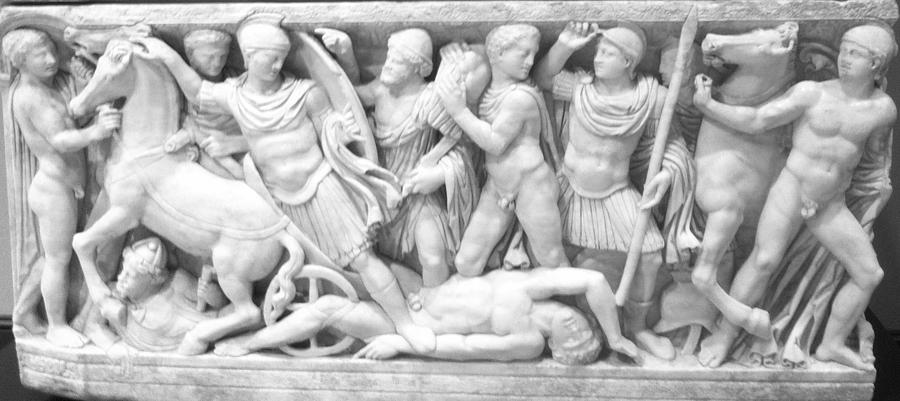

https://www.periodpaper.com/products/1890-print-relief-sculpture-roman-marcomanni...

Перевести · This is an original 1890 black and white relief line-block print of a relief sculpture depicting the battle with the Marcomanni which were a Germanic tribe. This probably occurred in the 2nd century AD when the Marcomanni allied with the Vandals, Quadi, and Sarmatians against the Roman …

What kind of armor did the Romans wear?

What kind of armor did the Romans wear?

They were armed with little protective armor and that quite light (milites levis armaturae); carried light round shields (parmae), and bore spears (hastae) much lighter than the heavy Pilaissued to the legionaries.

www.digitalattic.org/home/war/romanarmy/

What was the military like in ancient Rome?

What was the military like in ancient Rome?

Others were formed into cohorts, armed, trained and disciplined in Roman fashion and commanded by Roman praefects. They were armed with little protective armor and that quite light ( milites levis armaturae ); carried light round shields ( parmae ), and bore spears ( hastae) much lighter than the heavy Pila issued to the legionaries.

www.digitalattic.org/home/war/romanarmy/

Who are the Centurions of a Roman legion?

Who are the Centurions of a Roman legion?

Cohorts, maniples and centuries were commanded by centurions. The first cohort of a legion was occasionally doubled in strength and was always composed of the most experienced and best-trained soldiers, if possible, men of over eight years' service ( cohors veterana) .

www.digitalattic.org/home/war/romanarmy/

Who was the commanding officer of the Roman army?

Who was the commanding officer of the Roman army?

In Caesar's time the term is ill-defined and consequently loosely applied. It usually means the commanding officer of auxiliaries, slingers, archers, cavalry or infantry organized in cohorts. Some were chiefs of countries fumish ing the contingents, and some were Romans.

www.digitalattic.org/home/war/romanarmy/

https://fineartamerica.com/art/paintings/roman+military

Перевести · Entry of the Turks of Mohammed II Painting. Benjamin Constant. $17. More from This Artist. Similar Designs. Pope Benedict XIV presenting the Encyclical Ex Omnibus to the Comte de Stainville Painting. Pompeo Girolamo Batoni. $17. 1 - 72 of 245 roman …

https://fineartamerica.com/art/paintings/prisoner

Перевести · Square. Panoramic Horizontal. Panoramic Vertical. Colors All. Similar Art. prisoner of war political prisoner the prisoner…

https://m.ebay.com/sch/i.html?_nkw=prisoner+of+war+art&_sop=12

Перевести · Wooden Napoleonic Prisoner Of War Model Of A Guillotine Folk Art Model Hand Made. Pre-Owned. $89.95. FAST 'N FREE. Buy It Now. …

https://www.romeartlover.it/Romanwar.html

Перевести · The war erupted in March 101 and it was justified by raids of the Dacians in the Roman region of Moesia (today's Bulgaria), but Trajan had been …

РекламаКупить War Более 2-х млн CD дисков в наличии и под заказ. · Москва · будни 10:00-19:00

РекламаУмная колонка Xiaomi Mi AI Speaker Art Белая по цене 5690 р · Москва · пн-вс 9:00-21:00

Продавец: KremlinStore. ОГРНИП: 310774603600752

Не удается получить доступ к вашему текущему расположению. Для получения лучших результатов предоставьте Bing доступ к данным о расположении или введите расположение.

Не удается получить доступ к расположению вашего устройства. Для получения лучших результатов введите расположение.

The Military Affairs of Ancient Rome &

Roman Art of War in Caesar's Time

©1947 The Military Service Publishing Company. Copyright Expired

Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)

These appendixes were written by Lt. Col. S.G. Brady for the Military Service Publishing Company's 1947 print of "Caesar's Gallic Campaigns" (page 182-230).

I believe the appendixes are one of the most comprehensive and condensely written texts I've read on the Roman art and science of war (a sort of brief, '101' introductory text). The author covers almost every aspect of the Roman war-machine, and draws a few interesting parallels between the Roman military and armies of more modern times (that is, up to the mid 20th century). I also appreciated his references to the original latin terms used by the Romans.

The Military Affairs of Ancient Rome: Appendix A

Caesar's legion was a body of infantrymen with a full strength of some 6,000-6,500 men. Actually, as in modern armies, the effective strength was at times much less, because of detachments, desertions, disease and death. The strength of some legions fell as low as 2,500.

Whatever its strength, the legion was the main tactical and administrative unit of the Roman army and bore the brunt of most of the fighting. Although the legal military age was from seventeen to forty-six, most recruits were between the ages of seventeen and twenty-five.

Composed exclusively of some drafted, but more Roman citizen volunteers, recruited from Italy and mainly from the valley of the Po, members of the legions became professional soldiers who, enlisted for a definite term of years, looked forward to a share in all booty taken and retirement allowances of land and money.

The legion, a body somewhat like our division, was divided into ten tactical units called cohorts, resembling our modern battalions. The cohorts were divided into three maniples or companies and the maniples into two centuries or platoons. Thus there were sixty centuries in a legion, each at full strength with a complement of one hundred men. Cohorts, maniples and centuries were commanded by centurions. The first cohort of a legion was occasionally doubled in strength and was always composed of the most experienced and best-trained soldiers, if possible, men of over eight years' service (cohors veterana) . All legionaries, like good soldiers anywhere, could at any time in addition to fighting, build, construct, design, erect and fortify.

In 58 B. C., Caesar had six legions, eight in 58-57 B. C., and ten in 53 B. C. All legions, like our divisions, were numbered according to date of enlistment and, in the time of the Empire, received in addition distinguishing names such as "Victrix", in much the same manner that we speak of the "Black Watch," "The Foreign Legion," "The Rough Riders," and "The Red One" etc.

These auxilia - and their very name indicates that they were not called upon to bear the brunt of the fighting - were not Roman citizens. In Caesar's army they were mostly Gauls, and were furnished by friendly or allied states or requisitioned from dependent and subject states. Good archers (sagittarii) came from Numidia and Crete and good slingers from the Balearic Isles. Caesar also had detachments from Illyricum and in 52 B. C. had a special task force of 10,000 Aeduan infantrymen.

Some units retained their native officers, dress, weapons and methods of fighting. Others were formed into cohorts, armed, trained and disciplined in Roman fashion and commanded by Roman praefects.

They were armed with little protective armor and that quite light (milites levis armaturae); carried light round shields (parmae), and bore spears (hastae) much lighter than the heavy Pila issued to the legionaries. Slingers and archers had very light or no armor and no helmets, and the latter, from the nature of their weapon, could not use shields. Their standards were vexilla, red or flame-colored banners.

While, like the auxiliary cavalry, of doubtful use in emergencies, they could because of their light armament be used for speed and not for shock against small enemy groups. They were also used to make a show of force to alarm the enemy, to forage, to assist in fortifying, to fight delaying actions, to screen and to assist the cavalry in pursuit. Other uses were as skirmishers, as flank guards in battle and as raiders.

Under Caesar, legions did not have cavalry integrally assigned, as had been the case previously. Roman citizens able to possess, equip and feed horses were now members of the officer class. So that Caesar's cavalry was ordinarily furnished by friendly, allied or conquered states, Spanish, Gallic and German. The Aedui and others furnished 4,000 horse for the first campaign against the Helvetii. The next year the Treveri furnished an additional supply. Probably Caesars total cavalry strength rarely exceeded 5,000 and sometimes went as low as 1,000, for example, in the Civil War. This cavalry was organized on a Roman basis into alae or regiments of about 480 men. Alae were subdivided into sixteen turmae or troops, each of thirty men. The lowest tactical unit was the decuria of ten men.

Being foreign mercenaries and serving for pay, the troopers were dismissed, furloughed to the reserve and allowed to go to their homes in the fall after the completion of the campaign and were reassembled in the spring. They were generally commanded by Roman officers, Praefecti Equitum. Troop commanders were known as Decuriones, and all subordinate officers were ordinarily natives. Standards were vexilla and were perhaps sea-blue in color.

Metal helmets (cassides) were worn, light shields (parmae) carried and darts, or light lances or spears, were issued. With this equipment the cavalry was no match for good infantry and in fact did not have too fine a fighting record. It was at times not trusted, and occasionally in battle was unreliable and lacked discipline and courage. For example, at the battle of Neuf-Mesnil, the discouraged Treveran cavalry quit cold. In another campaign, 5,000 Gallic cavalrymen were put to flight by a mere 800 men.

Nevertheless the cavalry was put to a variety of uses Napoleon and Caesar were alike in their use of mounted troops similar to those prescribed for modem horse cavalry. The cavalry would sometimes open a campaign by close-in and distant reconnaissance, by scouting, screening and making preliminary tests of the enemy strength. It was used for skirmishing, to make surprise attacks, to engage the enemy cavalry, to hold the enemy ground troops in check until the legions could arrive and to attack the enemy's flank. Other uses were as raiders and foragers, as flank guards both on the march and in battle and sometimes to begin the actual battle itself. But above all its main use was that sought by and reveled in by all true cavalrymen, the pursuit, the onset of hard-ridden, sweating, lathered horses and cutting, slashing, hacking, yelling troopers.

At the request of the commander, certain courageous and experienced soldiers who had earned distinction because of exceptional ability and loyalty, voluntarily re-enlisted for further active duty after their twenty-year retirement. Such men were known as Evocati. They were of course treated with marked consideration and accorded many special privileges, including a mount while on the march and exemption from all fatigue duty. They were given extra pay and could be promoted directly to the grade of centurion. They helped sustain the morale of the troops and were in general held up as models for all enlisted men to follow.

In the early Roman army there had been a separate corps of engineers (Fabri), but this organization had been abandoned before Caesars time. Ordnance and engineer work was performed by specially trained legionaries under the direction of men detailed to these tasks because of their skill. Their work included the construction of camps, fortifications, siege works and materiel, bridges, ships and ship repair; the repair of equipment, armor, weapons and artillery, and the building of winter quarters. The chief of engineers or the senior engineer officer was the Praefectus Fabrum.

Individuals detailed for this service, known as speculatores; sometimes could speak the Gallic language and occasionally used disguise. Trained scouts, generally mounted and acting in reconnaissance patrols, were called exploratores.

From the earliest times, when the commanders were Praetors to the end of the Republic, it was customary for each general to have a small body of picked and higher-paid men as his immediate personal bodyguard and escort. Such a group was called the Cohors Praetoria. Caesar does not appear to have had this guard, as he once told his favorite 10th Legion that it would be his Praetorian cohort. But under the Empire, the Praetorian Cohorts were organized into a definite corps of Household troops, the famous Praetorian Guard.

Officers' servants and grooms were slaves known as calones and were under military discipline. In addition other slaves were pack-masters, wagoners and mule-skinners (muliones).

These (mercatores or lixae) were freemen or freedmen who sold extra food, provisions, clothing, and supplies not government issue, and purchased booty and prisoners from the men, paying cash on the spot. Their "canteens" had to be set up outside of the camp rear gate, except in times of danger. On one occasion raiding Germans caught them while outside the camp walls and massacred them to a man.

In early times, the commander of an army of two or more legions was the consul, succeeded later by the proconsul or the propraetor in charge of a province. Caesar was the commanding general by virtue of his authority as Proconsul. Like the consuls, the proconsul had the military imperium or supreme power when outside the city, possessing absolute military authority. Only after expiration of his term of office could he be called to account for his acts as governor. At the beginning of his term the chief officer was called "Dux Belli".

After his first important victory, his soldiers would usually hail him as Imperator or General-in-chief. The title was then officially confirmed by the Senate, if the victory added territories to the Republic. This occurred in Caesar's case after his victory over the Helvetii in 58 B. C. Thereafter he was addressed as "Imperator" and wore the paludamentum, or cloak of reddish purple, a long flowing garment of fine wool, decorated with gold embroidery, perhaps fringed and easily distinguished.

The office of quaestor, one of senatorial rank, was only quasi-military. The quaestors were elected by the people at Rome each year and were assigned to provinces by lot, each provincial governor and each army commander or imperator having one. In respect to the provinces they were in charge of its finance and revenues and acted as treasurers. In respect to the army they may be compared to our Quartermaster generals's and Chiefs of Finance. They purchased and were charge of supplies, provisions, clothing, arms, equipment, and shelter for the troops. In addition they guarded and supervised the sale of all booty and prisoners and paid the troops, having general administrative authority over all units. Ranking next to the commanding general, the Quaestor was one of his principal staff officers and in camp had special quarters (Quaestorium) near those of the commander (Praetorium or Principia). Sometimes put in command of troops, one commanded a legion in the first German campaign. Crassus and Antony were quaestors for Caesar.

The legati (lego, depute or commission) were men nominated by the proconsul and deputed or commissioned by the Senate as lieutenant or major generals under him. Caesar was allowed ten. This gave the commanding general a useful and efficient staff of general officers of experience who could be intrusted with the responsibility of command and military government or used as ambassadors. They were of senatorial rank, persons who had held at least a curule magistracy, i.e., been quaestors at Rome. The highest in rank, pro praetore, "for the commander", commanded the army in the absence of the General, could be put in charge of an independent force greater than one legion, and in general acted as chief of staff. Caesar, in the first German campaign introduced the custom of using his legati as legionary commanders, a duty previously exercised by the tribunes, but thereafter always performed by the lieutenant generals. Other duties might be in charge of recruiting, of all the cavalry, of constructing a fleet or commanding the winter camps of the troops. Among Caesar's outstanding lieutenant generals were the able and efficient Labienus, young Crassus, Aurunculeius Cotta, Quintus Cicero and Mark Antony. At different times during the years 58-52 B. C., Caesar had eighteen men who were his lieutenant generals.

There were six of these officers in a legion, and to Caesar's time they had been in command of this body, either alone or in pairs for two months. Caesar's tribunes were young men, well educated and of good social position, but in some cases inexperienced and owing their appointment by the general to political influence or personal friendship. They were of equestrian rank at least, having a property rating of 400,000 sesterces or about $20,000. Although some were experienced and capable officers, among whom was Caius Voiusenus, they usually were given less responsible duties, mainly of an administrative sort. They provided and looked after arms and equipment under the quaestor, tried military offenders, selected sites for the camps, superintended the building of same, sometimes commanded detached cohorts or groups of cohorts and were even placed in command of ships. They also discharged men, could be used as adjutants and staff officers for the general and the lieutenant generals, and were in charge of marches, interior guards and camp discipline.

In Caesar's time the term is ill-defined and consequently loosely applied. It usually means the commanding officer of auxiliaries, slingers, archers, cavalry or infantry organized in cohorts. Some were chiefs of countries fumish ing the contingents, and some were Romans. The Roman praefects were, like the tribunes, in some cases young men who had seen little military service. These two grades constituted the lowest "commissioned" officers, and like all officers were distinguished from the men by cuirasses made of gilded bronze metal and shaped to fit the contours of the body. There was a Praefectu

Hairy Pussy Movies Mature Russian

Betting Tips Private Club Apk

Sissy Gang Bang Porno Hd

Furry Anal Dildo

Bi Beeq Sex

Roman Warrior Painting at PaintingValley.com | Explore ...

Roman art: “a dace soldier prisoner of Roman soldiers ...

The Military Affairs of Ancient Rome & Roman Art of War in ...

Portchester Castle: from Roman Fort to Prisoner-of-War ...

1890 Print Relief Sculpture Roman Marcomanni Battle War ...

Roman Military Paintings | Fine Art America

Prisoner Paintings | Fine Art America

prisoner of war art for sale | eBay

Two Roman Wars in the reliefs of Trajan's Column

Roman War Prisoner Art