Roman Latin

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

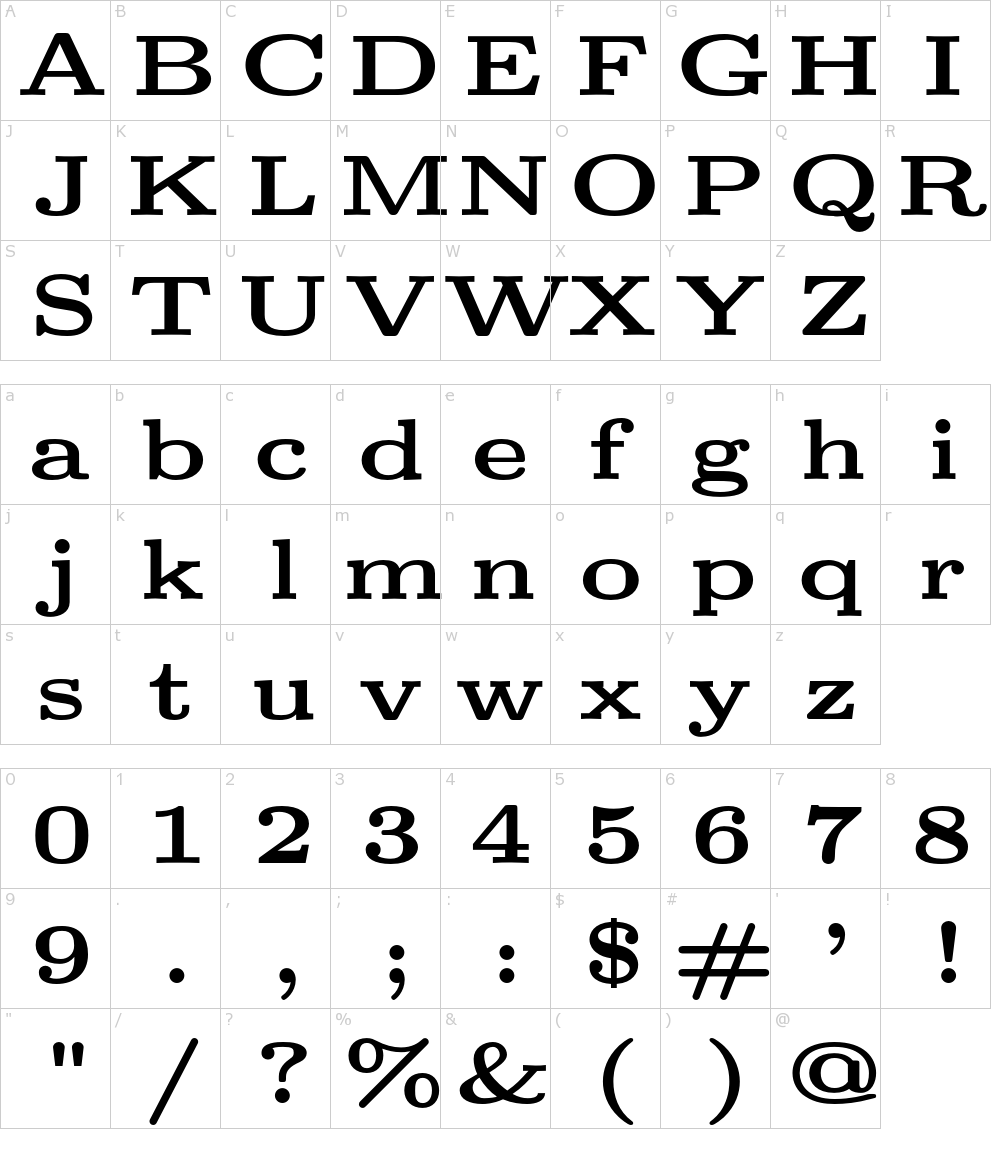

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

Afrikaans

Albanian

Amharic

Arabic

Armenian

Azerbaijani

Basque

Belarusian

Bengali

Bosnian

Bulgarian

Catalan

Cebuano

Chichewa

Chinese

Corsican

Croatian

Czech

Danish

Dutch

Esperanto

Estonian

Farsi

Filipino

Finnish

French

Frisian

Galician

Georgian

German

Greek

Gujarati

Haitian Creole

Hausa

Hebrew

Hindi

Hmong

Hungarian

Icelandic

Igbo

Indonesian

Irish

Italian

Japanese

Javanese

Kannada

Kazakh

Khmer

Korean

Kurdish

Kyrgyz

Lao

Latin

Latvian

Lithuanian

Luxembourgish

Macedonian

Malagasy

Malay

Malayalam

Maltese

Maori

Marathi

Mongolian

Burmese

Nepali

Norwegian

Polish

Portuguese

Punjabi

Romanian

Russian

Samoan

Scots Gaelic

Serbian

Sesotho

Shona

Sinhala

Slovak

Slovenian

Somali

Spanish

Sundanese

Swahili

Swedish

Tajik

Tamil

Telugu

Thai

Turkish

Ukrainian

Urdu

Uzbek

Vietnamese

Welsh

Xhosa

Yiddish

Yoruba

Zulu

Another word for

Opposite of

Meaning of

Rhymes with

Sentences with

Find word forms

Translate from English

Translate to English

Words With Friends

Scrabble

Crossword / Codeword

Words starting with

Words ending with

Words containing exactly

Words containing letters

Pronounce

Find conjugations

Find names

To Afrikaans

To Albanian

To Amharic

To Arabic

To Armenian

To Azerbaijani

To Basque

To Belarusian

To Bengali

To Bosnian

To Bulgarian

To Catalan

To Cebuano

To Chichewa

To Chinese

To Corsican

To Croatian

To Czech

To Danish

To Dutch

To Esperanto

To Estonian

To Farsi

To Filipino

To Finnish

To French

To Frisian

To Galician

To Georgian

To German

To Greek

To Gujarati

To Haitian Creole

To Hausa

To Hebrew

To Hindi

To Hmong

To Hungarian

To Icelandic

To Igbo

To Indonesian

To Irish

To Italian

To Japanese

To Javanese

To Kannada

To Kazakh

To Khmer

To Korean

To Kurdish

To Kyrgyz

To Lao

To Latin

To Latvian

To Lithuanian

To Luxembourgish

To Macedonian

To Malagasy

To Malay

To Malayalam

To Maltese

To Maori

To Marathi

To Mongolian

To Burmese

To Nepali

To Norwegian

To Polish

To Portuguese

To Punjabi

To Romanian

To Russian

To Samoan

To Scots Gaelic

To Serbian

To Sesotho

To Shona

To Sinhala

To Slovak

To Slovenian

To Somali

To Spanish

To Sundanese

To Swahili

To Swedish

To Tajik

To Tamil

To Telugu

To Thai

To Turkish

To Ukrainian

To Urdu

To Uzbek

To Vietnamese

To Welsh

To Xhosa

To Yiddish

To Yoruba

To Zulu

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

^ Livy , Ab urbe condita , 1:32

^ Jump up to: a b c Livy , Ab urbe condita , 1:33

^ Livy , Ab urbe condita , 1:35

^ Livy , Ab urbe condita , 1:38

^ Livy , Ab urbe condita , 2.14

^ Livy , Ab urbe condita , 2.16

^ Livy , Ab urbe condita , 2.17

^ Livy , Ab urbe condita , 2:18

^ Livy , Ab urbe condita , 2:19–20

^ Livy , Ab urbe condita , 2.22 , 24

^ Livy, 6.2.3–4 ; Plutarch, Camillus 33.1 (who does not mention the Hernici)

^ Livy, 6.6.2–3

^ Livy, 6.6.4–5

^ Livy, 7.7.1

^ Livy, 6.8.4–10

^ Livy, 6.10.6–9

^ Livy, 6.11.9

^ Livy, 6.12.1

^ Livy, 6.12.6–11 & 6.13.1–8

^ Livy, 6.14.1

^ Livy, 6.17.7–8

^ Livy, 6.15.2

^ Cornell, T. J. (1995). The Beginnings of Rome- Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000–264 BC) . New York: Routledge. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-415-01596-7 .

^ Oakley, S. P. (1997). A Commentary on Livy Books VI-X, Volume 1 Introduction and Book VI . Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 353–356. ISBN 0-19-815277-9 .

^ Oakley, pp. 446–447

^ Cornell, pp. 306, 322–323

^ Oakley, p. 338

^ Livy, 6.21.2–9

^ Livy, 6.22.1–3

^ Cornell, p. 322

^ Oakley, pp. 356, 573–574

^ Jump up to: a b Oakley, p. 357

^ Livy, 6.22.3–4 ; Plutarch, Camillus 37.2

^ Livy, 6.22.7–24.11

^ Plutarch, Camillus 37.3–5

^ Okley, p. 580

^ Livy, 6.25.1–5

^ Plutarch, Camillus 38.1

^ Livy, 6.25.5–26.8 ; D.H. xiv 6; Plutarch, Camillus 38.1–4; Cass. fr. 28.2

^ Jump up to: a b Cornell, p. 323, Oakley p. 357

^ Forsythe, Gary (2005). A Critical History of Early Rome . Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 257. ISBN 0-520-24991-7 .

^ Cornell, p. 323-324, Oakley p. 357

^ Oakley p. 603-604

^ Livy, 6.27.3–29.10

^ D.H., XIV 5

^ Fest. 498L s.v. trientem tertium

^ D.S, xv.47.8

^ Livy, 6.30.8

^ Cornell, p. 323; Oakley, p. 358; Forsythe, p. 258

^ Oakley, pp. 358, 608–609

^ Oakley, p. 608

^ Forsythe, p. 258

^ Forsythe, p. 206

^ Livy, 6.32.4–33.12

^ Oakley, pp. 642–643

^ Oakley, p. 352

^ Oakley, p. 359

^ Oakley, S. P. (1998). A Commentary on Livy Books VI-X, Volume 2 Books VII-VII . Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-19-815226-2 .

^ Oakley, p. 5-6

^ Livy, 7.11.2–11

^ Livy, 7.12.1–5

^ Oakley, pp. 7, 151

^ Livy, 7.12.7

^ Livy, 7.15.12

^ Cornell p.324; Oakley, p. 5

^ Oakley, p. 7

^ Livy, 7.17.2

^ Livy, 7.18.1–2

^ Livy, 7.19.1–2

^ D.S., xvi.45.8

^ Oakley, pp. 6, 193, 196; Forsythe p. 277

^ Oakley, p. 6

Wiki Loves Monuments: your chance to support Russian cultural heritage!

Photograph a monument and win!

The Roman–Latin wars were a series of wars fought between ancient Rome (including both the Roman Kingdom and the Roman Republic ) and the Latins , from the earliest stages of the history of Rome until the final subjugation of the Latins to Rome in the aftermath of the Latin War .

The Latins first went to war with Rome in the 7th century BC during the reign of the Roman king Ancus Marcius .

According to Livy the war was commenced by the Latins who anticipated Ancus would follow the pious pursuit of peace adopted by his grandfather, Numa Pompilius . The Latins initially made an incursion on Roman lands. When a Roman embassy sought restitution for the damage, the Latins gave a contemptuous reply. Ancus accordingly declared war on the Latins. The declaration is notable since, according to Livy, it was the first time that the Romans had declared war by means of the rites of the fetials . [1]

Ancus Marcius marched from Rome with a newly levied army and took the Latin town of Politorium by storm. Its residents were removed to settle on the Aventine Hill in Rome as new citizens, following the Roman traditions from wars with the Sabines and Albans . When the other Latins subsequently occupied the empty town of Politorium, Ancus took the town again and demolished it. [2] Further citizens were removed to Rome when Ancus conquered the Latin towns of Telleni and Ficana . [2]

The war then focused on the Latin town of Medullia . The town had a strong garrison and was well fortified. Several engagements took place outside the town and the Romans were eventually victorious. Ancus returned to Rome with much loot. More Latins were brought to Rome as citizens and were settled at the foot of the Aventine near the Palatine Hill , by the temple of Murcia . [2]

When Rome was ruled by Lucius Tarquinius Priscus the Latins went to war with Rome on two occasions.

On the first, which according to the Fasti Triumphales occurred prior to 588 BC, Tarquinius took the Latin town of Apiolae by storm, and from there brought back a great amount of loot to Rome. [3]

On the second occasion, Tarquinius subdued the entirety of Latium, and took a number of towns that belonged to the Latins or which had revolted to them: Corniculum , old Ficulea , Cameria , Crustumerium , Ameriola , Medullia and Nomentum , before agreeing to peace. [4]

In 508 BC, Lars Porsena king of Clusium (at that time reputed to be one of the most powerful cities of Etruria ) departed Rome after ending his war against Rome by peace treaty. Porsena split his forces, and sent part of the Clusian army with his son Aruns to besiege the Latin city of Aricia . The Aricians sent for assistance from the Latin League, and also from the Greek city of Cumae . When support arrived, the Arician army ventured beyond the walls of the city, and the combined armies met the Clusian forces in battle. According to Livy, the Clusians initially routed the Arician forces, but the Cumaean troops allowed the Clusians to pass by, then attacked from the rear, gaining victory against the Clusians. Livy says the Clusian army was destroyed. [5]

In 503 BC two Latin towns, Pometia and Cora , said by Livy to be colonies of Rome, revolted against Rome. They had the assistance of the southern Aurunci tribe.

Livy says that a Roman army led by the consuls Agrippa Menenius Lanatus and Publius Postumius Tubertus met the enemy on the frontiers and was victorious, after which Livy says the war was confined to Pometia. Livy says many enemy prisoners were slaughtered by each side. [6] Livy also says that the consuls celebrated a triumph, however the Fasti Triumphales record that an ovation was celebrated by Postumius and a triumph by Menenius, both over the Sabines.

In the following year the consuls were Opiter Virginius and Sp. Cassius . Livy says that they attempted to take Pometia by storm, but then resorted to siege engines. However the Aurunci launched a successful sally, destroying the siege engines, wounding many, and nearly killing one of the consuls. The Romans retreated to Rome, recruited additional troops, and returned to Pometia. They rebuilt the siege engines and when they were about to take the town, the Pometians surrendered. The Aurunci leaders were beheaded, the Pometians sold into slavery, the town razed and the land sold. Livy says the consuls celebrated a triumph as a result of the victory. [7] The Fasti Triumphales record only one triumph, by Cassius (possibly over the Sabines although the inscription is unclear).

In 501 BC word reached Rome that thirty of the Latin cities had joined in league against Rome, at the instigation of Octavius Mamilius of Tusculum . Because of this (and also because of a dispute with the Sabines ), Titus Lartius was appointed as Rome's first dictator , with Spurius Cassius as his magister equitum . [8]

However war with the Latins did not come to pass until at least two years later.

In 499 BC, or possibly 496 BC, war broke out. At first Fidenae was besieged (although it is not clear by whom), Crustumerium was captured (again it is not clear by whom), and Praeneste defected to the Romans. Aulus Postumius was appointed dictator, with Titus Aebutius Elva as his magister equitum. With the Roman army, they marched into the Latin territory and were victorious at the Battle of Lake Regillus . [9]

Shortly afterwards, in 495 BC, the Latins resisted calls from the Volsci to join with them to attack Rome, and went so far as to deliver the Volscian ambassadors to Rome. The Roman senate, in gratitude, granted freedom to 6,000 Latin prisoners, and in return the Latins sent a crown of gold to the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in Rome. A great crowd formed, including the freed Latin prisoners, who thanked their captors. Great bonds of friendship were said to have arisen between the Romans and the Latins as a result of this event. The Latins also warned Rome of the Volscian invasion which occurred shortly after in the same year [10]

In 493 a treaty, the Foedus Cassianum , was concluded, establishing a mutual military alliance between the Latin cities with Rome as the leading partner. A second people, the Hernici , joined the alliance sometime later. While the precise workings of the Latin League remains uncertain, its overall purpose seems clear. During the 5th century the Latins were threatened by invasion from the Aequi and the Volsci , as part of a larger pattern of Sabellian -speaking peoples migrating out of the Apennines and into the plains. Several peripheral Latin communities appear to have been overrun, and the ancient sources record fighting against either the Aequi, the Volsci, or both almost every year during the first half of the 5th century. This annual warfare would have been dominated by raids and counter-raids rather than the pitched battles described by the ancient sources.

In 390 a Gaulish warband first defeated the Roman army at the Battle of the Allia and then sacked Rome. According to Livy the Latins and Hernici, after a hundred years of loyal friendship with Rome, used this opportunity to break their treaty with Rome in 389. [11] In his narrative of the years that followed, Livy describes a steady deterioration of relations between Rome and the Latins. In 387 the situation with Latins and Hernici was brought up in the Roman senate, but the matter was dropped when news reached Rome that Etruria was in arms. [12] In 386 the Antiates invaded the Pomptine territory and it was reported in Rome that the Latins had sent warriors to assist them. The Latins claimed they had not sent aid to the Antiates, but had not prohibited individuals from volunteering for such service. [13] A Roman army under Marcus Furius Camillus and P. Valerius Potitus Poplicola met the Antiates at Satricum . In addition to Volscians the Antiates had brought a large number of Latins and Hernicians to the field. [14] In the battle that followed the Romans were victorious and the Volscians were slaughtered in great number. The Latins and Hernicians now abandoned the Volscians, and Satricum fell to Camillus. [15] The Romans demanded to know from the Latins and Hernici why for the last few years' wars they had not furnished any contingents. They claimed not to have been able to supply troops due to fear of Volscian incursions. The Roman senate considered this defence to be insufficient, but that time was not right for war. [16] In 385 the Romans appointed Aulus Cornelius Cossus Dictator to deal with the Volscian war. [17] The Dictator marched his army into the Pomptine territory, which he had heard was being invaded by the Volscians. [18] The Volscian army was once again swelled by Latins and Hernici, including contingents from the Roman colonies of Circeii and Velitrae , and in the battle that followed the Romans were once again victorious. The majority of the captives were found to be Hernici and Latins, including men of high rank, which the Romans took as proof that their states were formally assisting the Volscians. [19] However the sedition of Marcus Manlius Capitolinus prevented Rome from declaring war on the Latins. [20] When the Latins, Hernici, and the colonists of Circeii and Velitrae tried to persuade the Romans to release those of their countrymen who had been made prisoner, they were refused. [21] That same year Satricum was colonized with 2,000 Roman citizens, each to receive two and a half jugera of land. [22]

Some modern historians have questioned Livy's portrayal of the Latins as rebelling from Rome. Cornell (1995) believes that there was no armed uprising of Latins, rather the military alliance between Rome and the other Latin towns seems to have been allowed to wither. In the preceding decades Rome had grown considerably in power, especially with the conquest of Veii , and the Romans might now have preferred freedom of action to the obligations of the alliance. Also, several Latin towns appear to have remain allied to Rome; based on later events these would have included at least Tusculum and Lanuvium to which Cornell adds Aricia , Lavinium and Ardea . The colonies of Circeii and Velitrae are likely to have remained partly inhabited by Volsci, which helps explain their rebellion, but these two settlements more than any other Latin towns would have felt vulnerable to Rome's aggressive designs for the Pomptine region . [23]

Division among the Latins is also the stance taken by Oakley (1997) who substantially accepts Cornell's analysis. The continued loyalty of Ardea, Aricia, Gabii, Labicum , Lanuvium and Lavinium would help explain how Roman armies could operate in the Pomptine region. [24] In their writings on the early Roman Republic Livy and Dionysius of Halica

https://www.wordhippo.com/what-is/the/latin-word-for-238a1843d81dd7fbe80b5c1b99515c4ba8c94d0d.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman%E2%80%93Latin_wars

American Pie Naked Mile

Gif Cumshot On Dolly Girl

Threesome Video Vk

How to say roman in Latin - WordHippo

Roman–Latin wars - Wikipedia

Latin - Wikipedia

Latin Roman шрифт - fonts-online.ru

Spoken Roman Latin, from TV Show "Barbarians" - YouTube

Dictionar online roman - latin, latin - roman

roman - Wiktionary

Latin alphabet - Wikipedia

Roman Latin