Robert Koch Was A Prominent German

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

For other people named Robert Koch, see Robert Koch (disambiguation).

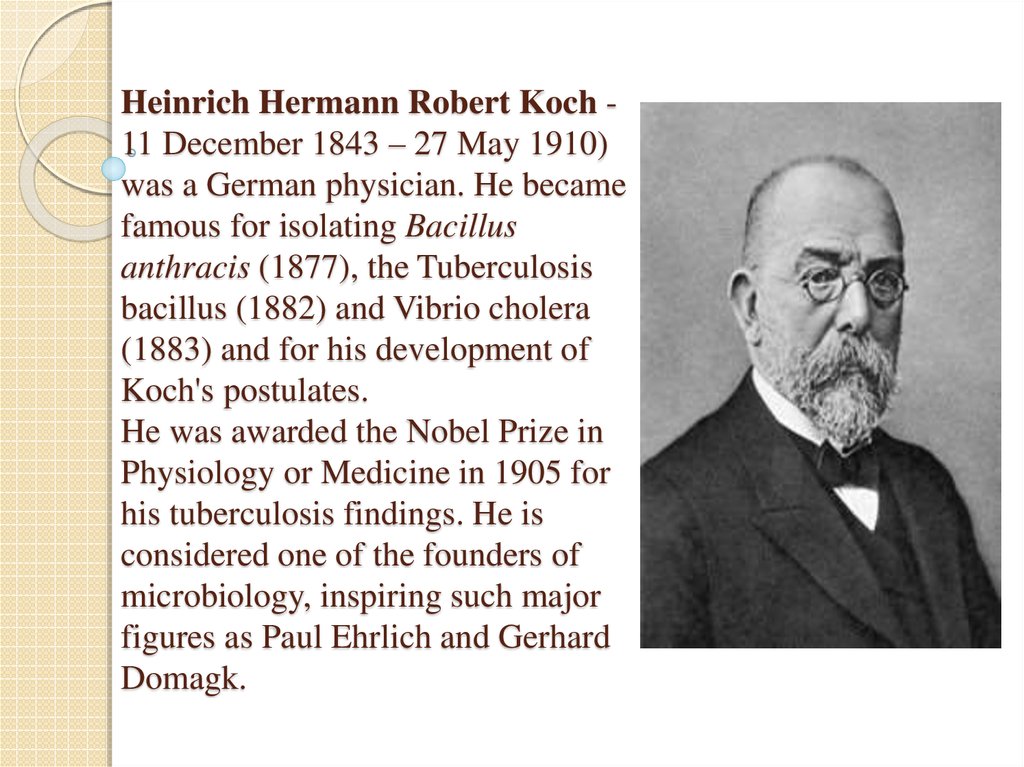

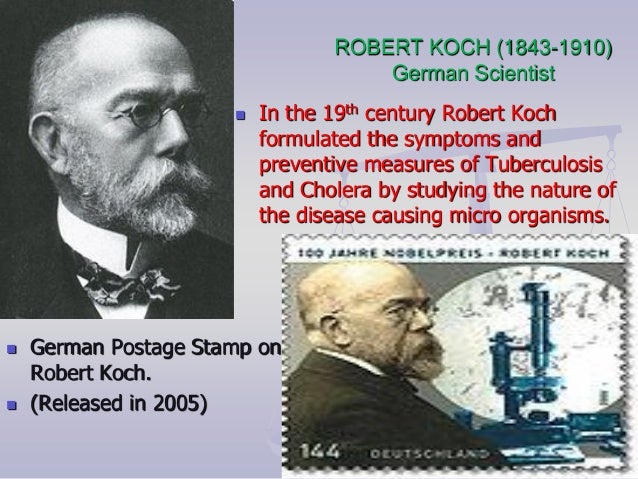

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch (English: /kɒk, kɒx/;[1][2] German: [ˈʁoː.bɛʁt kɔx] (listen); 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera, and anthrax, he is regarded as one of the main founders of modern bacteriology. As such he is popularly nicknamed the father of microbiology (with Louis Pasteur[3]), and as the father of medical bacteriology.[4][5] His discovery of the anthrax bacterium (Bacillus anthracis) in 1876 is considered as the birth of modern bacteriology.[6] His discoveries directly provided proofs for the germ theory of diseases, and the scientific basis of public health.[7]

Imperial Health Office, Berlin

University of Berlin

While working as a private physician, Koch developed many innovative techniques in microbiology. He was the first to use oil immersion lens, condenser, and microphotography in microscopy. His invention of bacterial culture method using agar and glass plates (later developed as Petri dish by his assistant Julius Richard Petri) made him the first to grow bacteria in laboratory. In appreciation of his works, he was appointed as government advisor at the Imperial Health Office in 1880, promoted to a senior executive position (Geheimer Regierungsrath) in 1882, Director of Hygienic Institute and Chair (Professor of hygiene) of the Faculty of Medicine at Berlin University in 1885, and the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases (later renamed Robert Koch Institute after his death) in 1891.

The methods Koch used in bacteriology led to establishment of a medical concept known as Koch's postulates, four generalized medical principles to ascertain the relationship of pathogens with specific diseases. The concept is still in use in most situations and infuences subsequent epidemiological principles such as the Bradford Hill criteria.[8] A major controversy followed when Koch discovered tuberculin as a medication for tuberculosis which was proven to be ineffective, but developed for diagnosis of tuberculosis after his death. For his research on tuberculosis, he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1905.[9] The day he announced the discovery of tuberculosis bacterium, 24 March is observed by the World Health Organization as "World Tuberculosis Day" every year since 1982.

Koch was born in Clausthal, Germany, on 11 December 1843, to Hermann Koch (1814–1877) and Mathilde Julie Henriette (née Biewend; 1818–1871).[10] His father was a mining engineer. He was the third of thirteen siblings.[11] He excelled academically from an early age. Before entering school in 1848, he had taught himself how to read and write.[12] He completed secondary education in 1862, having excelled in science and math.[13]

At the age of 19, in 1862, Koch entered the University of Göttingen to study natural science.[14] He took up mathematics, physics and botany. He was appointed assistant in the university's Pathological Museum.[15] After three semesters, he decided to change his area of study to medicine, as he aspired to be a physician. During his fifth semester at the medical school, Jacob Henle, an anatomist who had published a theory of contagion in 1840, asked him to participate in his research project on uterine nerve structure. This research won him a research prize from the university and enabled him to briefly study under Rudolf Virchow, who was at the time considered as "Germany's most renowned physician."[11] In his sixth semester, Koch began to research at the Physiological Institute, where he studied the secretion of succinic acid, which is a signaling molecule that is also involved in the metabolism of the mitochondria. This would eventually form the basis of his dissertation.[9] In January 1866, he graduated from the medical school, earning honours of the highest distinction, maxima cum laude.[16][17]

After graduation in 1866, Koch briefly work as an assistant in the General Hospital of Hamburg. In October that year he moved to Idiot's Hospital of Langenhagen, near Hanover, as a general physician. In 1868, he moved to Neimegk and then to Rakwitz in 1869. As the Franco-Prussian War started in 1870, he enlisted in the German army as a volunteer surgeon in 1871 to support the war effort.[15] He was discharged a year later and was appointed as a district physician (Kreisphysikus) in Wöllstein in Prussian Posen (now Wolsztyn, Poland). As his family settled there, his wife presented him a microscope as a birthday gift. With the miscroscope, he set up a private laboratory and started his career in microbiology.[16][17]

Koch began conducting research on microorganisms in a laboratory connected to his patient examination room.[14] His early research in this laboratory yielded one of his major contributions to the field of microbiology, as he developed the technique of growing bacteria.[18] Furthermore, he managed to isolate and grow selected pathogens in pure laboratory culture.[18] His discovery of anthrax bacillus (later named Bacillus anthracis) hugely impressed Ferdinand Julius Cohn, professor at the University of Breslau (now University of Wrocław), who helped him publish the discovery in 1876.[15] Cohn had established the Institute of Plant Physiology[19] and invited Koch to demonstrate his new bacterium there in 1877.[20] Koch was transferred as district physician at Breslau in 1879. A year after, he left for Berlin as he was appointed as government advisor at the Imperial Health Office, where he worked from 1880 to 1885.[21] Following his discovery of tuberculosis bacterium, he was promoted to Geheimer Regierungsrath, a senior executive position in June 1882.[22]

In 1885, Koch received two appointments as an administrator and professor at Berlin University. He became Director of Hygienic Institute and Chair (Professor of hygiene) of the Faculty of Medicine.[15] In 1891, he relinquished his professorship and became a director of the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases (now Robert Koch Institute) which consisted of a clinical division and beds for the division of clinical research. For this he accepted harsh conditions. The Prussian Ministry of Health insisted after the 1890 scandal with tuberculin, which Koch had discovered and intended as a remedy for tuberculosis, that any of Koch's inventions would unconditionally belong to the government and he would not be compensated. Koch lost the right to apply for patent protection.[23] In 1906, he moved to East Africa to research a cure for trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). He established the Bugula research camp where up to 1000 people a day were treated with the experimental drug Atoxyl.[24]

Robert Koch made two important developments in microscopy; he was the first to use an oil immersion lens and a condenser that enabled smaller objects to be seen.[11] In addition, he was also the first to effectively photography (microphotography) for microscopic observation. He introduced the "bedrock methods" of bacterial staining using methylene blue and Bismarck (Vesuvin) brown dye.[7] In an attempt to grow bacteria, Koch began to use solid nutrients such as potato slices.[18] Through these initial experiments, Koch observed individual colonies of identical, pure cells.[18] He found that potato slices were not suitable media for all organisms, and later began to use nutrient solutions with gelatin.[18] However, he soon realized that gelatin, like potato slices, was not the optimal medium for bacterial growth, as it did not remain solid at 37 °C, the ideal temperature for growth of most human pathogens.[18] And also many bacteria can hydrolyze gelatin making it a liquid. As suggested to him by his post-doctoral assistant Walther Hesse, who got the idea from his wife Fanny Hesse, in 1881, Koch started using agar to grow and isolate pure cultures.[25] Agar is a polysaccharide that remains solid at 37 °C, is not degraded by most bacteria, and results in a stable transparent medium.[18][26]

Koch's booklet published in 1881 titled "Zur Untersuchung von Pathogenen Organismen" (Methods for the Study of Pathogenic Organisms)[27] has been known as the "Bible of Bacteriology."[28][29] In it he described a novel method of using glass slide with agar to grow bacteria. The method involved pouring a liquid agar on to the glass slide and then spreading a thin layer of gelatin over. The gelatin made the culture medium solidify by which bacterial samples were introduced. The whole bacterial culture was then put in a glass plate together with a small wet paper. Koch named this container as feuchte Kammer (moist chamber). The typical chamber was a circular glass dish 20 cm in diameter and 5 cm in height and had a lid to prevent contamination. The glass plate and the transparent culture media made observation of the bacterial growth easy.[30]

Koch publicly demonstrated his plating method at the Seventh International Medical Congress in London in August 1881. There, Louis Pasteur exclaimed, "C'est un grand progrès, Monsieur!" ("What a great progress, Sir!")[16] It was using Koch's microscopy and agar-plate culture method that his students discovered new bacteria. Friedrich Loeffler discovered the bacteria of glanders (Burkholderia mallei) in 1882 and diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae) in 1884; and Georg Theodor August Gaffky, the bacterium of typhoid (Salmonella enterica) in 1884.[31] Koch's assistant Julius Richard Petri developed an improved method and published it in 1887 as "Eine kleine Modification des Koch’schen Plattenverfahrens" (A minor modification of the plating technique of Koch).[32] The culture plate was given an eponymous name Petri dish.[33] It is often asserted that Petri developed a new culture plate,[11][34][35] but is was not so. He simply discarded the use of glass plate and instead used the circular glass dish directly, not just as moist chamber, but as the main culture container. This further reduced chances of contaminations.[25] It would also have been appropriate if the name "Koch dish" had been given.[30]

Robert Koch is widely known for his work with anthrax, discovering the causative agent of the fatal disease to be Bacillus anthracis.[36] He published the discovery in a booklet as "Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, Begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus Anthracis" (The Etiology of Anthrax Disease, Based on the Developmental History of Bacillus Anthracis) in 1876 while working at in Wöllstein.[37] His publication in 1877 on the structure of anthrax bacterium[38] marked the first photography of a bacterium.[11] He discovered the formation of spores in anthrax bacteria, which could remain dormant under specific conditions.[14] However, under optimal conditions, the spores were activated and caused disease.[14] To determine this causative agent, he dry-fixed bacterial cultures onto glass slides, used dyes to stain the cultures, and observed them through a microscope.[39] His work with anthrax is notable in that he was the first to link a specific microorganism with a specific disease, rejecting the idea of spontaneous generation and supporting the germ theory of disease.[36]

During his time as the government advisor with the Imperial Department of Health in Berlin in the 1880s, Robert Koch became interested in tuberculosis research. At the time, it was widely believed that tuberculosis was an inherited disease. However, Koch was convinced that the disease was caused by a bacterium and was infectious. In 1882, he published his findings on tuberculosis, in which he reported the causative agent of the disease to be the slow-growing Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[18] He published the discovery as "Die Ätiologie der Tuberkulose" (The Etiology of Tuberculosis),[26] and presented before the Berlin Physiological Society on 24 March 1882. Koch announced, saying,

When the cover-glasses were exposed to this staining fluid [methylene blue mixed with potassium hydroxide] for 24 hours, very fine rod-like forms became apparent in the tubercular mass for the first time, having, as further observations showed, the power of multiplication and of spore formation and hence belonging to the same group of organisms as the anthrax bacillus... Microscopic examination then showed that only the previously blue-stained cell nuclei and detritus became brown, while the tubercle bacilli remained a beautiful blue.[16][17]

There was no particular reaction to this announcement. Eminent scientist such as Rudolf Virchow remained skeptical. Virchow clung to his theory that all diseases are due to faulty cellular activities.[40] On the other hand, Paul Ehrlich later recollected that this moment was his "single greatest scientific experience."[5] Koch expanded the report and published under the same title as a booklet in 1884, in which he concluded that the discovery of tuberculosis bacterium fulfilled the three principles, eventually known as Koch's postulates, which were formulated by his assistant Friedrich Loeffler in1883, saying:

All these factors together allow me to conclude that the bacilli present in the tuberculous lesions do not only accompany tuberculosis, but rather cause it. These bacilli are the true agents of tuberculosis.[40]

In August 1883, the German government sent a medical team led by Koch to Alexandria, Egypt, to investigate cholera epidemic there.[41] Koch soon found that the intestinal mucosa of people who died of cholera always had bacterial infection, yet could not confirm whether the bacteria were the causative pathogens. As the outbreak in Egypt declined, he was transferred to Calcutta (now Kolkata) India, where there was a more severe outbreak. He soon found that the river Ganges was the source of cholera. He performed autopsies of almost 100 bodies, and found in each bacterial infection. He identified the same bacteria from water tanks, linking the source of the infection.[11] He isolated the bacterium in pure culture on 7 January 1884. He subsequently confirmed that the bacterium was a new species, and described as "a little bent, like a comma."[42] His experiment using fresh blood samples indicated that the bacterium could kill red blood cells, and he hypothesized that some sort of poison was used by the bacterium to cause the disease.[11] [The poison was discovered by an Indian scientist Sambhu Nath De in 1959 and is known as cholera toxin.[43]] Koch reported his discovery to the German Secretary of State for the Interior on 2 February, and published it in the Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (German Medical Weekly) the following month.[44]

Although Koch was convinced that the bacterium was the cholera pathogen, he could not entirely establish a critical evidence the bacterium produced the symptoms in healthy subjects (following Koch's postulates). His experiment on animals using his pure bacteria culture did not cause the disease, and correctly explained that animals are immune to human pathogen. The bacterium was then known as "the comma bacillus", and scientifically as Bacillus comma.[45] It was later realised that the bacterium was already described by an Italian physician Filippo Pacini in 1854,[46] and was also observed by the Catalan physician Joaquim Balcells i Pascual around the same time.[47][48] But they failed to identify the bacterium as the causative agent of cholera. Koch's colleague Richard Friedrich Johannes Pfeiffer correctly identified the comma bacillus as Pacini's vibrioni and renamed it as Vibrio cholera in 1896.[49]

Koch gave much of his research attention on tuberculosis throughout his career. After medical expeditions to various parts of the world, he again focussed on tuberculosis from the mid-1880s. By that time the Imperial Health Office was carrying out a project for disinfection of sputum of tuberculosis patients. Koch experimented with arsenic and creosote as possible disinfectants. These chemicals and other available drugs did not work.[11] His report in 1883 also mentioned a failed experiment on an attempt to make tuberculosis vaccine.[22] By 1888, Koch turned his attention to synthetic dyes as antibacterial chemicals. He developed a method for examining antibacterial activity by mixing the gelatin-based culture media with a yellow dye, auramin. His notebook indicates that by February 1890, he tested hundreds of compounds.[5] In one of such tests, he found that an extract from the tuberculosis bacterium culture dissolved in glycerine could cure tuberculosis in guinea pigs. Based on a series of experiments from April to July 1891, he could conclude that the extract did not kill the tuberculosis bacterium, but destroyed (by necrosis) the infected tissues, thereby depriving bacterial growth. He made a vague announcement in August 1890 at the Tenth International Congress of Medicine in Berlin,[40] saying,

In a communication which I made a few months ago to the International Medical Congress [in London in 1881], I described a substance of which the result is to make laboratory animals insensitive to inoculation of tubercle bacilli, and in the case of already infected animals, to bring the tuberculous process to a halt.[16][17] I can tell […] that much, that guinea pigs, which are highly susceptible to the disease [tuberculosis], no longer react upon inoculation with tubercle virus [bacterium] when treated with that substance and that in guinea pigs, which are sick (with tuberculosis), the pathological process can be brought to a complete standstill.[5]

By November 1890, Koch was able to show that the extract was effective in humans as well.[50] Many patients and doctors went to Berlin to get Koch's remedy.[11] But his experiments showed that tuberculosis infected guinea pigs developed severe symptoms when the substance was inoculated. The severity was more so in humans.[40] This development of sever immune response, which is now known to be due to hypersensitivity, is known as the "Koch phenomenon."[51] The chemical nature was not known, and among several independent experiments done by the next year, only his son-in-law, Eduard Pfuhl, was able to reproduce similar results.[5] It nevertheless became a medical sensation, and the unknown substance was referred to as "Koch's Lymph." Koch published his experiments in the 15 January 1891 issue of Deutsche Medicinische Wochenschrift,[52][53] and The British Medical Journal immediately published the English version simultaneously.[54] The English version was also reproduced in Nature,[55] and The Lancet in the same month.[56] The Lancet presented it as "glad tidings of great joy."[50] Koch simply referred to the medication as "brownish, transparent fluid."[12] Josephs Pohl-Pincus had used the name tuberculin in 1844 for tuberculosis culture media,[57] and Koch subsequently adopted as "tuberkulin."[58]

The first report on the c

Boobs Sleep

Hairy Aunt Tattoo Doggystyle Anal

Baby Young Girls

Sia Siberia Dildo

Zoo Sex Dog Fucked

Robert Koch Was A Prominent German Bacteriologist ...

Robert Koch - Wikipedia

Robert Koch

Text B. Robert Koch — Студопедия

Robert Koch | German bacteriologist | Britannica

Студопедия — Text B. Robert Koch

Robert Koch is a prominent German bacteriologist, the ...

Robert Koch is a prominent German bacteriologist, the ...

Robert Koch Was A Prominent German