Rethinking the key concepts of hypnosis

Vladimir Snigur MDOriginally published in the Antology of the Russian Psychotherapy and Psychology, DOI 10.54775/PPL.2023.74.50.001.

The aim of this work is to make a step towards creating a unified structure and understanding of the essential components and mechanisms of hypnosis. The role of the ideodynamic effect as a central mechanism of hypnosis, the importance of psychological and social factors that moderate the hypnotic response and make up the “frame” of hypnosis, and the positive feedback mechanism as an elementary unit of hypnotic intervention, are examined. The concept of hypnotic resistance is conceptualized in terms of the feedback mechanisms. Parallels are drawn with some approaches that use near-hypnotic and experiential elements, in order to identify more precisely the features unique to hypnosis, and a range of issues requiring further investigation is outlined.

Keywords: hypnosis, suggestion, ideodynamics, resistance, feedback loop

In the modern theoretical understanding of hypnosis, there are three directions: neodissociative, sociocognitive, and interactive-phenomenological (Lynn & Kirsch, 2006). Attempts have been made to define hypnosis, integrating to some extent the theoretical and practical ideas and taking into account the complexity of hypnosis as an entity. Different authors have emphasized different aspects of hypnosis. Elkins et al. (2015) have tracked the development of the definition of hypnosis pointing out the relation between hypnosis-as-procedure vs hypnosis-as-product. Zeig (1988) has taken the phenomenological perspective, emphasizing the importance of considering hypnosis from the perspective of a patient, a therapist, and an observer, as well as the importance of context - defining a situation as “hypnosis”. Short (2018) in his definition of conversational hypnosis has focused on the intentional use of suggestion to activate automatic / dissociated response.

There is still no consensus on what constitutes the nature of hypnosis, especially when one considers not only the clinical / experimental context, but also other options for its use, such as stage hypnosis. In addition, there are difficulties in linking hypnosis to mainstream psychotherapeutic approaches. The following questions are offered as a starting point for setting the context of the story:

● What is the relationship between suggestion and hypnosis?

● What’s the difference between hypnosis and other experiential interventions?

● What are the fundamental components of hypnosis that are applicable both to practice and teaching?

● How does hypnosis combine the formal aspect (hypnosis-as-procedure), the relational aspect (hypnosis as a model of relationships), the interactive aspect (hypnosis as a way of communication) and the intrapsychic aspect (hypnosis-as-state)?

● How does hypnosis fit into the psychotherapeutic process? Where does it “begin” and where does it “end”?

In an attempt to approach these questions, it is proposed to deconstruct hypnosis as a single entity into several components: the mechanism of hypnosis, the core phenomena of hypnosis, the hypnotic frame. Basing on this, a definition of hypnosis and of its elementary unit will be given.

The analysis presented here is based on the author’s psychotherapeutic work with outpatients, on the experience of teaching clinical hypnosis to healthcare professionals, and on an extensive eight-year experience of translating training seminars in collaboration with colleagues from cognitive-behavioral, psychodynamic and other areas of psychotherapy. Difficulties arising in the field of hypnosis education have recently become more often considered, and the insufficient attention paid to this topic is recognized (e.g., Shugarman, 2017). When faced with the need to teach the basics of hypnosis to specialists of various profiles, challenges arise including the need to find universal terminology that fits well with the different psychotherapeutic approaches.

Ideodynamics as the key mechanism of hypnosis

The ideomotor effect has been known since the mid-19th century and implies unconscious fulfillment of motor acts resulting from the involuntary motor realization of an idea. The ideomotor effect is known in the field of hypnosis in terms of classical hypnotic phenomena like automatic writing, hypnotic catalepsy, arm levitation, etc. However, the effect of the spontaneous realization of an idea is not confined to the motor sphere only. Suggestion can cause shifts in all areas of subjective experience: in the cognitive, affective, sensory, motor, and even autonomic spheres (Erickson & Rossi, 1979). Therefore, such automatic effect in terms of the spontaneous realization of an idea could be more broadly designated as ideodynamic effect. The term was coined by Daniel Noble, MD, in his lecture “On ideas, and their dynamic influence” (Noble, 1854).

It is worth noting that the ideodynamic effect cannot be attributed exclusively to hypnosis and suggestion. There is a consensus among many hypnosis experts that most hypnotic phenomena can be observed in everyday life. The ideodynamic effect can be observed on a daily basis outside the context of hypnosis, trance, or altered states of consciousness. Freud in his classic work “The Psychopathology of Everyday Life” (1914) described many examples of what he called parapraxis — lapses, oversights, which apparently result from spontaneous manifestations of repressed or suppressed thoughts.

Thus, the ideodynamic effect is the involuntary realization of an idea in subjective experience. It can manifest in cognitive, affective, motor, sensory, autonomic sphere. It may be immediate or deferred.

How can one judge the involuntary quality of behavior? It is characterized by a combination of the following features:

● surprise / novelty effect,

● relative subjective unpredictability,

● relative subjective uncontrollability,

● lack of sense of agency,

● manifestations in the areas of subjective experience with limited susceptibility to volitional influence.

The immediate ideodynamic effect can be observed as a result of suggestions involving various modalities and implying an immediate reaction, for example, changes in the sensory, motor sphere, and affective sphere. As an example of the deferred ideodynamic effect, one can consider the seeding of ideas, post-hypnotic suggestions, some forms for the cognitive restructuring, and other strategic interventions.

In fact, it can be stated with great confidence that the ideodynamic effect is the central mechanism of hypnosis. Suggestion, in this case, is any communication that causes ideodynamic response and contains an explicit or implicit declaration of the involuntary effect being induced.

Hypnosis as facilitation of the ideodynamic effect

Hypnosis can greatly enhance this effect and make it more manageable. From a technical point of view, the mechanism of facilitating the ideodynamic effect was described by Erickson and Rossi (Erickson & Rossi, 1976), which implies (1) the fixation of attention, (2) depotentiating conscious sets, (3) unconscious search, (4) unconscious processes, and (5) hypnotic response. Regardless of the specific technical implementation, the result of the procedure, which we call hypnotic induction, is a certain state of awareness, characterized by certain core phenomena described in detail by Ericksonian authors. Zeig (1988) describes four phenomena of hypnosis: changes in attention, changes in intensity, changes in responsiveness, and changes in dissociation. The former two are immediately related: focused attention, along with a deepening of dissociation, naturally leads to an increase in the intensity of something which takes the focus of attention, and weakening of the “background”. Therefore, it makes sense to combine them and thus highlight three core phenomena (Fig. 1).

Interventions aimed at shifts in these three areas constitute the essence of hypnotic induction. Hypnotic techniques are immediate communicative signals of varying complexity geared to change the focus of attention, the degree of interpersonal responsiveness and dissociation, which contributes to the strengthening of the ideodynamic effect, which, in turn, allows to create therapeutic changes or experimental effects.

Based on this, the following broad definition of hypnosis is proposed: hypnosis is the process of using communicative signals by one person to purposefully elicit stable ideodynamic effects in other person or in group of people.

We can judge whether a particular interaction can be called “hypnosis” by the presence of the purposeful elicitation of the ideodynamic effect, i.e. the spontaneous realization of ideas conveyed to the subject and / or arising in his own mind.

However, the mere use of hypnotic techniques aimed at creating the phenomena described above is not enough to create a stable ideodynamic effect. The effectiveness of hypnotic techniques is directly related to the concept of hypnotizability and the discussion of whether all people are susceptible to hypnosis. Studies show that both the structural features of the brain and the functional connectivity between the brain regions may play an important role in hypnotic response (Faymonville et al., 2003; Jiang et al., 2016; Hoeft et al., 2012; Jensen et al., 2015; Landry, 2017). However, there are psychological and social factors to be considered before hypnotic induction can be utilized. These factors provide a frame in which hypnotic induction and therapeutic / experimental work takes place.

The Frame of Hypnosis

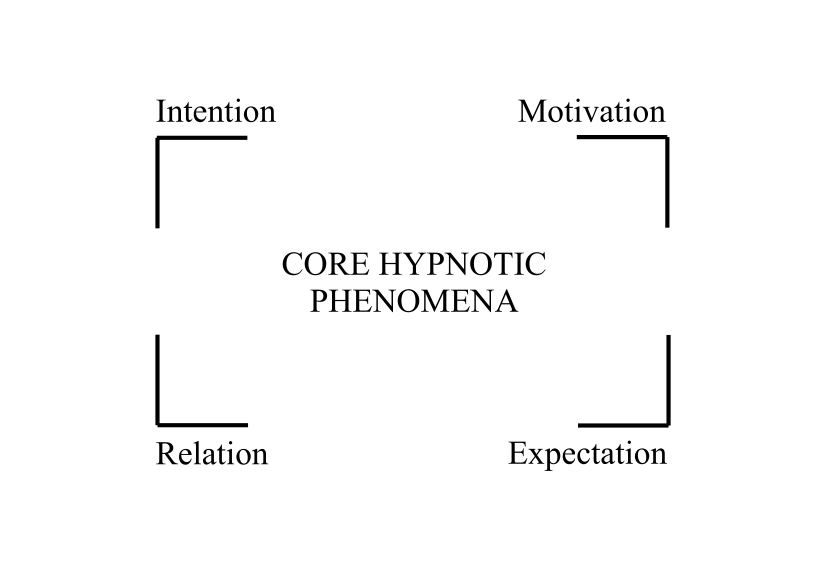

The frame of hypnosis is a set of interpersonal and intrapersonal factors that moderate the effectiveness of hypnotic techniques. Psychological and social factors as the moderators of hypnotic response have been mentioned by hypnosis theorists (Hammond, 2005; Lynn, 2006; Jensen et al., 2015; Lynn et al., 2017). Instead of considering separately the cognitive, social, contextual and other variables, with a purpose of practical convenience the four interrelated focal points are proposed (Fig. 2).

Relation

Relation characterizes the model of the relationship between the therapist and the patient. Relation can range from a more authoritarian to a more collaborative model. It may be significantly influenced by the unconscious processes of both the therapist and the patient. In analytical terms, in may concern the quality of object relations, transference-countertransference.

Intention

Intention is characterized by the goal the patient sets entering into a therapeutic relationship and giving consent to the use of hypnosis. Indirectly, it is associated with the motivational components, but reflects, rather, the conscious layer of goal-setting. It is not always possible to trace the patient's distinct conscious goal, especially in acute situations, but it is a therapist’s responsibility to get a sense of a shared goal from which the patient would benefit.

Motivation

The degree and the sources of motivation affect the quality of the patient’s involvement and the general level of expectancy and arousal, where the optimal level of motivation and positive expectancy contribute to the most favorable performance. Low motivation leads to low involvement, excessively high motivation may lead to burnout and disappointment.

Expectations

Expectations characterize the patient’s concrete internal attitudes regarding what will happen during the hypnosis session and the general course of interaction with the specialist. Basically, the expectations constitute the important sources of internal reinforcement.

All four components contribute to the quality of hypnotic rapport.

Positive Feedback Loop

But hypnotic induction is characterized not only by facilitation of the ideodynamic effect, but also by its stabilization and utilization in order to create lasting changes in the subjective reality of the subject. What makes it possible to develop a stable ideodynamic effect?

Erickson & Rossi (1979) described the ratification technique, which essentially constitutes external reinforcement for the induced ideodynamic effects. A wider Ericksonian concept of utilization can be seen as a generalization of this idea, including also the internal reinforcement which occurs (1) due to the patient’s modeling of the therapist’s behavior (“I am utilizing my own internal processes”), (2) due to the dissociative attitude conveyed by the therapist (“Not knowing, not doing”, that is, not relying on volitional effort and conscious planning), and (3) due to the focus of attention, which intensifies the “figure” and blurs the “background” of what is happening. Basically, utilization and ratification techniques facilitate the external reinforcement for the ideodynamic effects.

Gilligan (1981) uses the concept of interpersonal feedback, which is established within the hypnotic rapport. The idea of intrapsychic feedback is discussed mainly by nonclinical authors (Tripp, 2020a). The idea of positive feedback leads to the elementary unit of the hypnotic process, the hypnotic feedback loop (Fig. 3). It is a stable psychic positive feedback between an idea and its ideodynamic realization through internal and / or external reinforcement. The hypnotic feedback loop is closely related to the interpersonal feedback loop of the rapport, which serves as a source of external reinforcement for the ideodynamic effect.

First, joining with the subjective reality of the subject, the hypnotist uses suggestion to induce an ideodynamic effect. For instance, the hypnotist suggests imagining a sensation of lightness in the subject’s hand. Then the hypnotist uses verbal feedback from the subject and/or his own observations to pick up the autonomic responses to this suggestion, which can manifest in form of numbness, tickling, spontaneous muscle contractions etc., in order to ratify them and feed back to the subject, intensifying and acknowledging the effect and thus closing the loop.

The concept of hypnotic trance as a state, which is traditionally the first “stop” on the path of hypnotic induction, is associated with a persistent feedback loop involving different areas of subjective experience based on the concept of “sleep” or “relaxation”. However, some forms of hypnosis may not involve the concepts of “trance,” “sleep,” “relaxation,” but include the same three core phenomena: narrowed attention, interpersonal responsiveness, and dissociation (e.g., Short, 2018; Bányai 2018). Some techniques for creating hypnotic phenomena in an alert state (James Tripp, personal communication, 2017; e.g., Tripp, 2020b) focus primarily on building a frame and eliciting isolated ideodynamic effects in different areas of internal experience (for example, glove anaesthesia, induced paralysis, hallucinations, amnesia, etc.). The hypnotist begins with a simpler ideodynamic effects, for instance, ideosensory or ideomotor one, establishing stable positive feedback and then proceeding to more complex ones. In this sense, the feedback loops are interconnected in a manner of chain.

Here is an example of such a chain in experimental hypnosis: Left arm levitation — Numbness of the left hand — Induced left arm paralysis — Induced right arm paralysis with glove anesthesia — Induced legs paralysis — Name amnesia.

Several patterns concerning the hypnotic loops are curious to explore. First, a more complex hypnotic phenomenon is often easier to elicit by first establishing a loop with a simpler phenomenon. For example, one subject may find it easier to develop catalepsy than anaesthesia. If arm catalepsy is first elicited, then it may be much easier to elicit glove anesthesia, which, in turn, facilitates more complex phenomena like hallucinations or amnesia. Secondly, feedback loops can be transformed, when one phenomenon transforms into another, or they can overlap, when in the presence of two loops, primary and secondary, the secondary one is functionally connected with the primary, and the primary loop continues to function while the secondary loop is functional. With the collapse of the primary loop, the secondary one also collapses.

In clinical work, such chains of loops often begin with the state of hypnotic trance, wherefrom further work with imagery, memories, ego-states, or other phenomena is developed. But this model conceptualizes trance just as one of the phenomena of hypnosis rather than its inherent trait.

Resistance

From this perspective, resistance can be considered at two levels: at the level of establishing the frame and at the level of forming a hypnotic feedback loop.

At the level of establishing the frame, resistance can be related to any of its elements: (1) excessively low or high motivation can negatively affect the degree of the subject’s involvement in the work; (2) unrealistic expectations (high, magical, fearful, etc.) require clarification and correction before the beginning of the hypnotic induction; (3) the absence of a shared goal or an unrealistic goal can also impair the degree of cooperation in hypnosis; and (4) the distortions in the transference-countertransference or inadequate role relationship can weaken the rapport.

At the level of a feedback loop, resistance can be conceived as negative feedback between an idea and its ideodynamic realization (Fig. 4). Many techniques of working with resistance described by Erickson include the utilization of reactions that occur in response to or in opposition to the ideodynamic effects of therapeutic suggestions. These reactions are accepted as desired and appropriate, then positive feedback is established for them, which can elicit confusion and deepen the hypnotic dissociation.

From this point of view, we can consider the widespread misconception about hypnosis, which is as follows: "If I am aware of what happened in hypnosis, then it was not real hypnosis." Metacognitive functioning alone may not result in negative feedback for the ideodynamic effect of therapeutic suggestions. Apparently, anxiety and/or the unconscious devaluation or denial of certain aspects of subjective experience may cause negative feedback, which does not allow the ideodynamic effect to gain a foothold and prevents the subject from becoming fully absorbed by hypnotic experience. Such processes are often observed in patients with severe personality disorders.

Conclusion

This model considers hypnosis as a psychotherapeutic process in miniature, where the elements of the frame make it possible to effectively apply the therapeutic techniques.

Any communication that causes an ideodynamic effect can be called suggestion. To be able to call a certain communication “hypnosis”, it is necessary: (1) to establish a frame that includes relation, intention, motivation and expectations, (2) to use techniques which create shifts in attention, responsiveness, and dissociation, (3) to elicit and enhance the ideodynamic effect, (4) to stabilize it through positive feedback and (5) to strategically sequence the feedback loops.

The elements of the hypnotic frame serve two main goals: securing the therapeutic rapport and establishing a framework of psychological factors, which constitutes the sources of the external and internal reinforcement accordingly.

The utilization of the ideodynamic effect is at the heart of therapeutic work in hypnosis, which occurs due to the establishment of persistent loops of positive feedback between ideas conveyed by the therapist or arising in the mind of the subject and their dynamic realizations, and the subsequent sequencing of these loops in form of strategic interventions.

This approach allows a line to be drawn between hypnosis and imagery-based interventions, such as imagery rescripting in Schema Therapy, which can also use the ideodynamic effect and deal with attention, responsiveness, and dissociation, but usually lack the constellation of the processes given above.

From an educational perspective, teaching hypnosis implies a certain set of skills for managing the hypnotic frame, managing the core phenomena of hypnosis, eliciting and stabilizing hypnotic feedback loops, and strategic sequencing of the loops.

Discussion

This model has shown to be beneficial in clinical work and convenient in teaching. However, it is heuristic in nature and raises questions that require more in-depth theoretical research. In particular, the very nature of the ideodynamic effect remains largely unexplored. For now, we might agree with the original statement by D. Noble:

The dynamic influence which peculiar ideas and trains of thought exert, under circumstances in which volitional agency is imperfect or altogether in abeyance, is curiously exhibited in the origin and progress of numerous mental maladies; and, in instances wherein there may be no actual insanity, the singular effects which at times result, as ideodynamic phenomena, have, in their significance, important practical relations. (Noble, 1854).

The role of hypnosis as a tool for modeling and researching psychopathology has already been discussed in the literature (e.g., Bell et al., 2011). The concept of an intrapsychic feedback loop may allow us to explain more fully the persistent effects of suggestion, to draw parallels with some models of psychopathology, such as the vicious circles found in anxiety (Clark, 1986) and depression (Beck et al., 1979), and to substantiate the further study of hypnotic interventions, which essentially draw on the same principle.

This model makes it possible to conceptualize the resistance to hypnosis. The mechanisms of the intrapsychic negative feedback regarding the ideodynamic effect are of particular interest to clinicians in order to understand the nature of resistance at the level of hypnotic induction. This kind of resistance may correlate with the functioning of primitive defenses of denial and idealization/devaluation, from a psychoanalytic perspective, or with the functioning of early maladaptive schemas, such as emotional inhibition or unrelenting standards, from the cognitive perspective. Psychological and social factors that constitute the hypnotic frame also appear to be related to the resistance to hypnosis and hypnotizability.

Some authors (e.g., Yapko, 2001; Alladin, 2010, 2016) have pointed out the importance of strategical sequencing of interventions. The concept of feedback loops and their sequencing can be a useful tool for conceptualizing such interventions.

References

Alladin, A. (2010) Evidence-based hypnotherapy for depression. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 58:2, 165-168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140903523194

Alladin, A., & Amundson, J. (2016) Cognitive hypnotherapy as a transdiagnostic protocol for emotional disorders. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 64:2, 147-166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2016.1131585

Bányai, É.I. (2018). Active-alert hypnosis: History, research, and applications. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 61(2), 88-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2018.1496318

Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B.F., Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press.

Bell V., Oakley, D.A., Halligan, P.W., Deeley, Q. (2011) Dissociation in hysteria and hypnosis: Evidence from cognitive neuroscience. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 82, 332-339. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2009.199158

Clark, D. M. (1986). A cognitive model of panic. Behavior Research and Therapy, 24, 461−470. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(86)90011-2

Erickson, M.H., Rossi, E.L., Rossi, S.I. (1976). Hypnotic realities: The induction of clinical hypnosis and forms of indirect suggestion. New York: Irvington Publishers.

Elkins, G. R., Barabasz, A.F., Coucil, J. R., Spiegel, D. (2015) Advancing research and practice: The revised APA definition of hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 63(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2014.961870

Erickson, M.H., Rossi, E.L. (1979). Hypnotherapy: An exploratory casebook. New York: Irvington Publishers.

Faymonville, M. E., Roediger, L., Fiore, G. D., Delgueldre, C., Phillips, C., Lamy, M., Luxen, A., Maquet, P., Laureys, S. (2003) Increased cerebral functional connectivity underlying the antinociceptive effects of hypnosis. Cognitive Brain Research, 17, 255-262. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0926-6410(03)00113-7

Freud, S. (1914). Psychopathology of everyday life. New York: The Macmillan company.

Gilligan, S.G. (1981). Ericksonian approaches to clinical hypnosis. In J.K. Zeig (Ed.). Ericksonian approaches to hypnosis and psychotherapy (pp. 87-103). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Hammond, D.C. (2005) An integrative, multi-factor conceptualization of hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 48:2-3. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2005.10401508

Hoeft, F., Gabrieli, J. D. E., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., Haas, B. W., Bammer, R., Menon, V., Spiegel, D. (2012) Functional brain basis of hypnotizability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(10), 1064-1072. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2190

Jensen, M.P., Adachi, T., Tomé-Pires, C., Lee, J., Osman, Z.J., Miró, J. (2015) Mechanisms of hypnosis: Toward the development of a biopsychosocial model. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 63(1), 34–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2014.961875

Jiang, H., White, M. P., Greicius, M. D., Waelde, L. C., & Spiegel, D. (2017) Brain activity and functional connectivity associated with hypnosis. Cerebral Cortex, 1, 27(8), 4083-4093. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw220

Landry, M., Lifshitz, M., Raz, A. (2017) Brain correlates of hypnosis: A systematic review and meta-analytic exploration. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Review, 81(Pt A), 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.020

Lynn, S.J., Kirsch, I. (2006). Essentials of clinical hypnosis: An evidence based approach. Washington, DC: American psychological association.

Lynn, S.J., Maxwell R, Green JP. (2017) The hypnotic induction in the broad scheme of hypnosis: A sociocognitive perspective. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 59(4), 363–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2016.1233093

Noble, D. (1854). Three lectures on the correlation of psychology and physiology. Association Medical Journal, 2(81), 642–646.

Short, D. (2018) Conversational hypnosis: Conceptual and technical differences relative to traditional hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 61(2), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2018.1441802

Sugarman, L.I. (2017) Exploring, evolving, and refining hypnosis education. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 59(3), 231–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2017.1247544

Tripp, J. (2020a, March 4). How Hypnosis Works (The Hypnotic Loop) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o0MKrCnWfa0

Tripp, J. (2020b, March 6). Hypnotic 'Jedi Skills' | Hypnosis Without Trance [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JY4c0BGXZPk

Yapko, M. D. (2001) Treating depression with hypnosis: integrating cognitive-behavioral and strategic approaches. New Tork: Routledge.

Zeig, J.K. (1988). An Ericksonian phenomenological approach to therapeutic hypnotic induction and symptom utilization. In J.K.Zeig & S.R.Lankton (Eds.), Developing Ericksonian therapy: State of the art (pp. 353-375). New York: Brunner/Mazel.