Reading To Female

👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Culture and Anarchy

Art still has truth. Take refuge there.

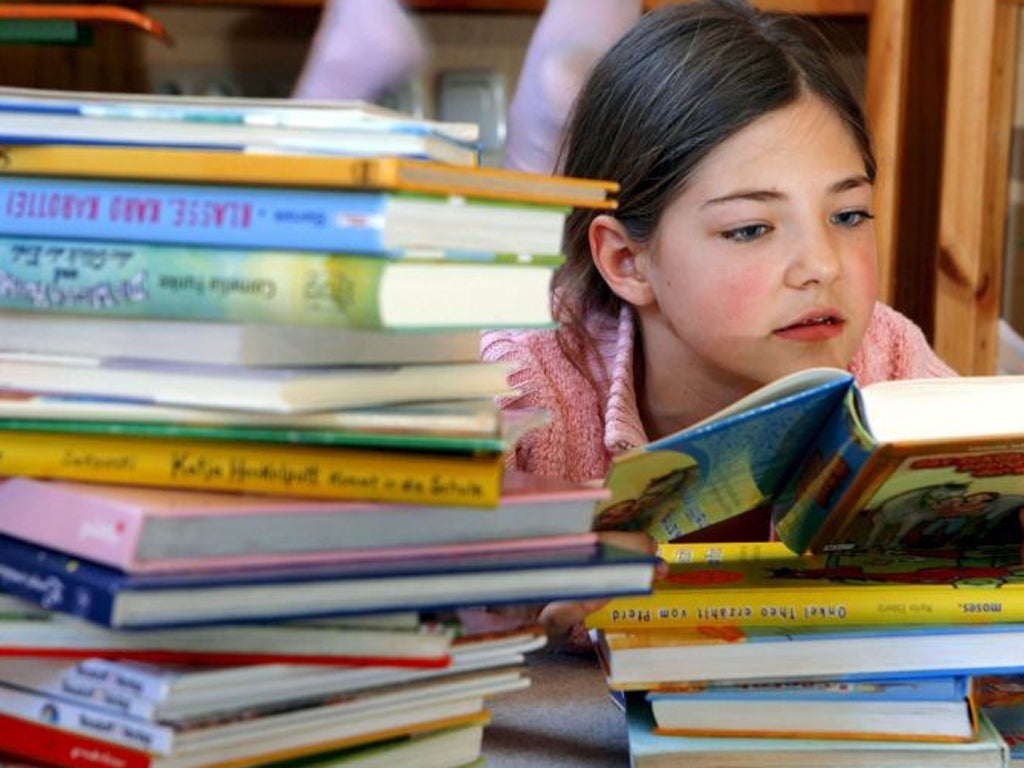

I have a particular fondness for paintings of women reading. I suppose this is because I spend so much time reading – and I like images that have a woman, alone, comfortable, engrossed in a book, ignoring whatever is going on around her (including the artist painting her). I love this 1933 painting by Henry Lamb (left), The Artist’s Wife, for this reason. I’ve just discovered the Tate’s Album facility, in which you can create your own digital exhibition drawing on their collection, so I decided to do one of pictures of women reading. There are quite a few, it turns out (although, of course, many from other collections, too). You can look at my album here. The range of images is fascinating – because, after all, women reading is a historically complex, socially-inflected topic. For centuries women were only encouraged to read the Bible, and, presumably, recipe books – that is, when they were literate enough to read anything, and many of the images I’ve chosen show a woman simply holding, or even near, a book, which at least indicates her ability to read. After all, why teach women to read when they could just memorise a few chunks of improving verses or household advice manuals? Although Jane Austen wrote in Pride and Prejudice that

“I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of any thing than of a book! — When I have a house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library.”

nonetheless there remained a strong suspicion that women, with their tendency to hysteria, emotional outbursts and rather weak minds, were much better off not reading novels, which might drive them over the edge. The psychological consequences of reading fiction were potentially severe, leading women to expect romance and excitement, alongside an increased tendency to swoon at the sight of a man. In fact, well into the nineteenth century there was a view that reading as part of learning could, if taken to extremes, be very bad for a woman’s mental and physical health; it would take all the blood from her womb (thus rendering her infertile) and move it to her head (thus making her insane). It would – apparently – also give her cold feet. I read a lot, and I do always have cold feet, but things seem otherwise well.

The moral panic about women’s reading – whether they should, and if so what they should – provides the context to these images of women reading. Many of them, unsurprisingly, show a woman reading in a devotional context. These are often the most sombre, beautiful images, showing a religious devotion which is pictured as sacred as well as picturesque. One of my favourites of these is Marianne Stokes, Candlemas Day (1901), which shows a very pious-looking girl, totally focused, reading by candlelight. Appropriately, another name for Candlemas is the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin, and this young lady looks very virginal indeed.

Another good reason for a woman to be reading, historically, was to share a (morally improving, no doubt) story with her children. That’s another good reason to educate women; so they can teach their offspring. Some of these are ghastly cloying images, such as Arthur Boyd Houghton’s Mother and Children Reading, but others, such as Harrington Mann’s The Fairytale, are less morally improving and more appealing. These domestic reasons for women reading are historically accurate, I suppose, but there are more interesting paintings, in my view: I was surprised by the number of eighteenth century women pictured with a book in their hand, or tucked under their arm.

Some of the women in the paintings are writers, and are thus depicted with a book to indicate their position as such. Robert Southey may have written to Charlotte Bronte that:

“Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life: & it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure she will have for it, even as an accomplishment & a recreation. To those duties you have not yet been called, & when you are you will be less eager for celebrity”

but literature – both writing and reading it – has, luckily, often been the business of a woman’s life, and many of the paintings reflect that. I love the famous Opie picture of Mary Wollstonecraft, looking up from her book severely but with just a tiny twinkle in her eye.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries clearly took it for granted that women might read as a pastime – but, interestingly, they increasingly abandoned their books in aesthetic langour. There are a lot of books put aside in this period, such as Harold Gilman’s Lady on a Sofa (1910) and Matisse’s The Inattentive Reader (1919). The reading woman, then, becomes a much more appealing subject for male painters, as an aesthetic object to be looked at – presumably because while she is reading, she’s not paying attention to who is watching. I’m particularly struck – not in a good way – by Theodore Roussel’s The Reading Girl (1886-7) – after all, we all read like that, don’t we? Who needs clothes to enjoy a book? Perhaps most appealing, then, is Gwen John’s sober depiction of A Lady Reading (1909-11), in which a young woman stands alone, so engrossed in her book she doesn’t even sit on the nearby chair. I understand that absorption, and the painting speaks much more to reading women than the male gaze.

There is continually a great difference between images of women reading by women and those by men. By men before the 19th century it’s almost always that the women is presented as sensually engaged; she is almost always pictured in sexy clothes, not overt but clearly there. Or she is luxuriously dressed; the upper class woman. The rhetoric against reading was it stirred people’s passions and of course this was dangerous for women. In the 19th century this is less a faultline but not lost. Women show women’s faces; they dwell on the details around the woman reading; her clothes are often plain, not sexy at all; she is reading for a purpose or her escape is intelligent. That last image is a return to Aretino (pornographer of the 16th century).

Thank you! Absolutely – that sums it up nicely! The Gwen John painting is, as you say, a very different approach, and women certainly paint women differently.

Reblogged this on West Coast Review and commented:

I too love paintings of women reading. Wonderful article!

I had assumed the original purpose of images of women reading was to indicate that bright women couldn’t play sport, hold down a job or travel abroad, but at least they could enjoy intellectual stimulation. But Bloomsbury women could do anything they wanted! So when Duncan Grant painted Interior with the Artist’s Daughter 1935, he was not suggesting that his and Vanessa Bell’s daughter Angelica had a limited life. Rather he might have been indicating that in the social and intellectual whirl that was his home, quiet reading was still a very great pleasure.

I love that painting. Yes, it indicates a vibrant inner life, being painted with a book – something I suppose women have only really been allowed to have for just over a century!

Your email address will not be published.

Notify me of new comments via email.

Privacy & Cookies: This site uses cookies. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use.

To find out more, including how to control cookies, see here: Cookie Policy

%d bloggers like this:

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

Последнее обновление: 44 недели назад

Erotic Video Download

Love Dick Milf

Rus Couples

Fit Milf

Boobs Machine

Women Reading – Culture and Anarchy

900+ Women reading ideas | woman reading, reading art ...

Women's Reading List

What I learnt from a year of reading only books by women ...

21 Books From The Last 5 Years That Every Woman Should ...

Free Text to Speech: Online, App, Software, Commercial ...

Amanda's Reading Room | Transgender and Cross-Dressing ...

Reading To Female

/woman-reading-a-book-on-sofa--117845380-5977a22c519de200119d6f32.jpg)