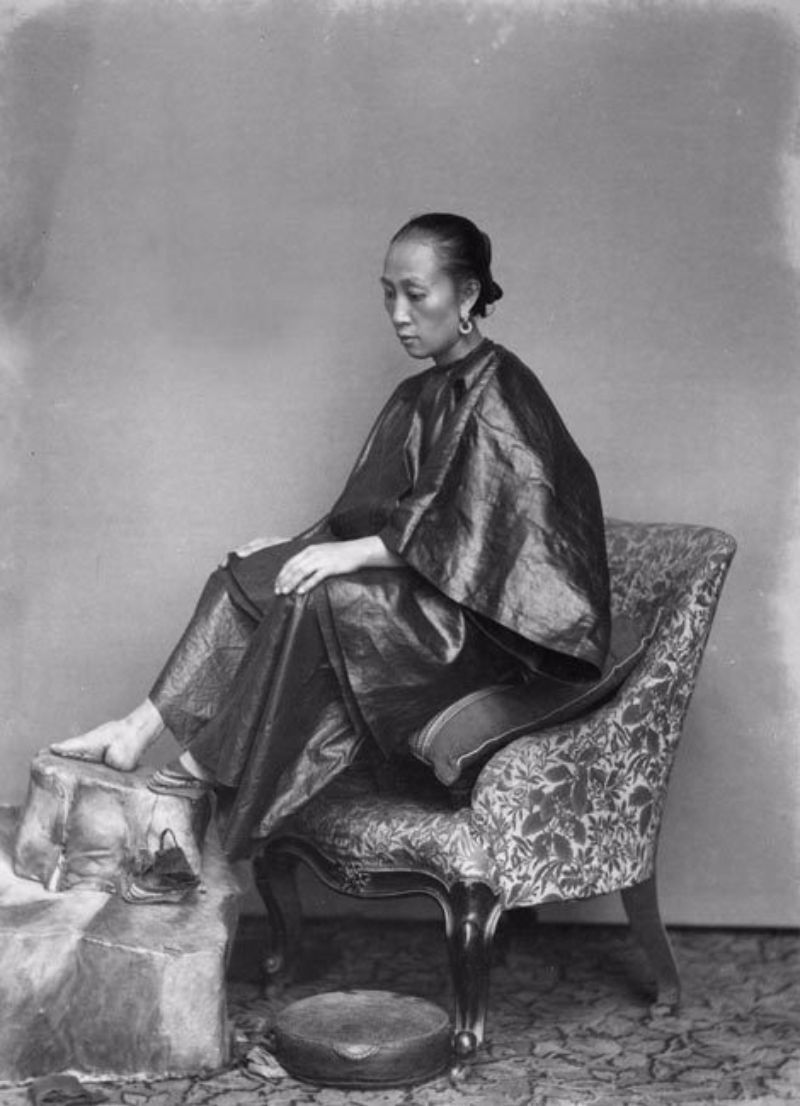

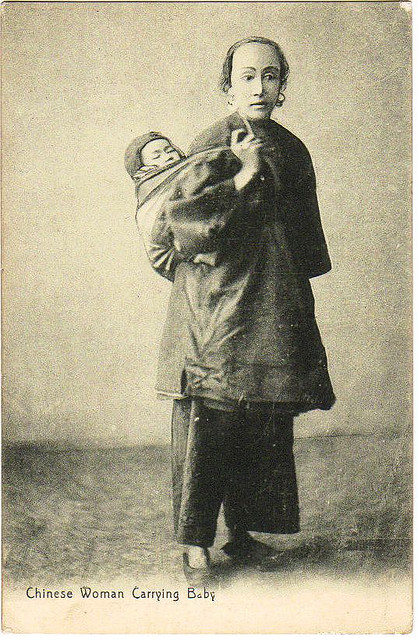

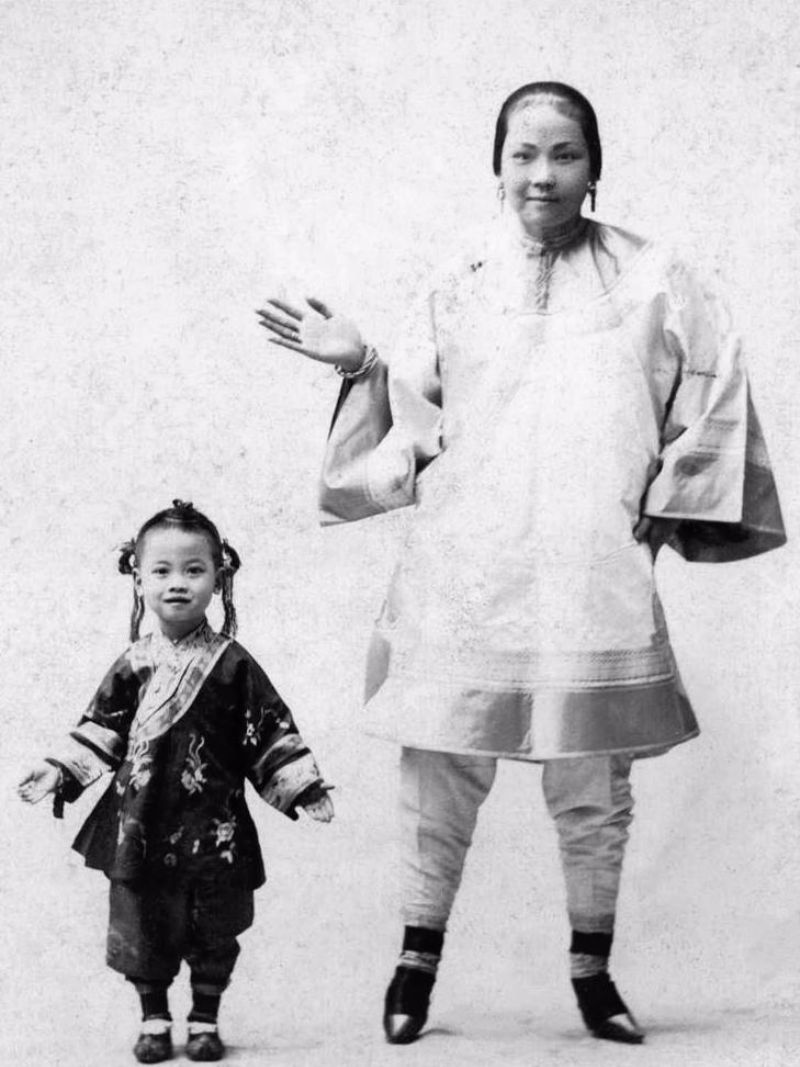

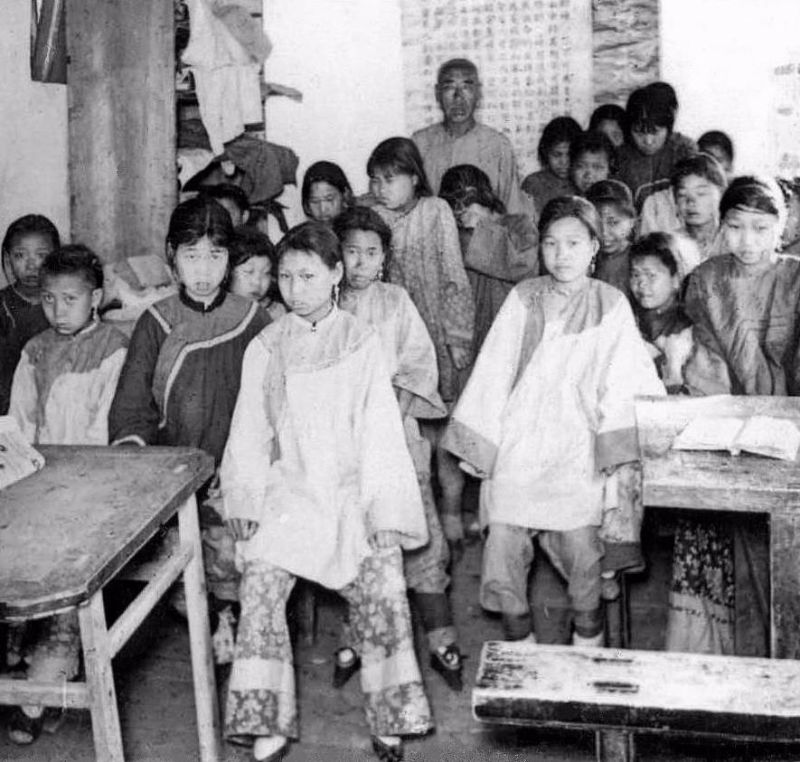

Rare Of Chinese Women

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

https://www.vintag.es/2012/08/rare-photographs-of-chinese-women-from.html?m=1

Перевести · 28.08.2012 · The Empress Dowager Cixi rose from the position of concubine to become the most powerful woman in …

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/378232068710058808

Перевести · These amazing 19th-century photographs of Chinese women offer a glimpse, however small, of what their lives may have been like. Image: Library of Congress “At home or abroad, in holiday robes or in plain clothing, the heart of a Chinese female …

https://asiandateladies.com/5-characteristics-all-traditional-chinese-women-have

Перевести · 03.02.2020 · 1. Chinese women are practical. It’s rare to find traditional Chinese women who regularly splurge on clothes, cosmetics and shoes. In fact, it’s rare to find a traditional Chinese woman who splurges at all. The Chinese, in general, are known for being practical and frugal. When you’re in a relationship with one, man or woman…

www.bathantiquesonline.com/search/antique/rare-chinese-woman/results-1.html?pass...

Перевести · Rare Chinese Woman for Sale: Browse TODAY's SELECTED Rare Chinese Woman for SALE, BEST OFFER and Auction. FIND 1000's of Antiques, Art, Vintage & RARE …

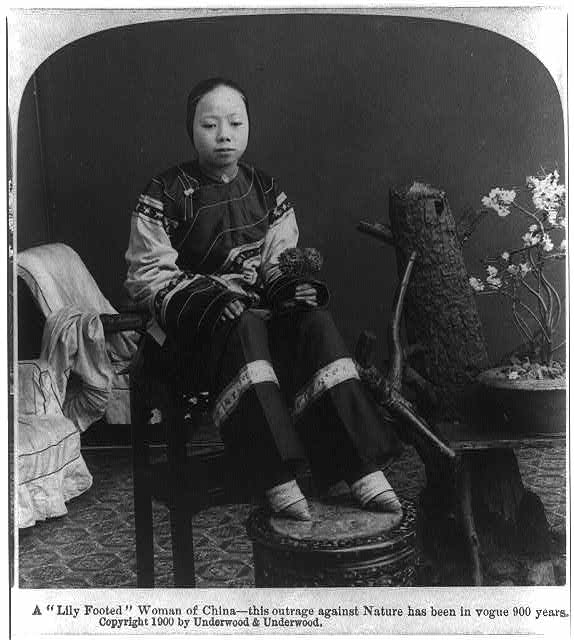

https://www.vintag.es/2017/02/bound-to-be-beautiful-30-rare-and-scary.html?m=1

Перевести · 02.02.2017 · Foot binding or bound feet was a custom practiced on young females for approximately one thousand years in China, from the tenth century until the early twentieth century. The practice originated among entertainers and members of the Chinese …

Are there any Chinese women who splurge on clothes?

Are there any Chinese women who splurge on clothes?

It’s rare to find traditional Chinese women who regularly splurge on clothes, cosmetics and shoes. In fact, it’s rare to find a traditional Chinese woman who splurges at all. The Chinese, in general, are known for being practical and frugal.

asiandateladies.com/5-characteristics-all-tr…

What is the status of women in China?

What is the status of women in China?

In addition, gender equality was personally important to 86 percent of Chinese female as of 2018. The place of Chinese women in society and family is currently still undergoing major transformations. Many women and girls are still facing discrimination, inequality and even violence, especially in rural areas.

www.statista.com/topics/4860/women-in-c…

What are the characteristics of a traditional Chinese woman?

What are the characteristics of a traditional Chinese woman?

Chinese women are practical. It’s rare to find traditional Chinese women who regularly splurge on clothes, cosmetics and shoes. In fact, it’s rare to find a traditional Chinese woman who splurges at all. The Chinese, in general, are known for being practical and frugal. When you’re in a relationship with one, man or woman,...

asiandateladies.com/5-characteristics-all-tr…

Is there a surplus of women in China?

Is there a surplus of women in China?

According to official estimates of 2019, the surplus of men among young adults of marriageable age of 20 to 24 years was almost 115 to 100. This infamous deficit of young Chinese females is naturally accompanied by several social, demographic and economic problems, including black markets for brides and increased age-gaps between spouses.

www.statista.com/topics/4860/women-in-c…

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/womens-blog/2016/aug/27/why-chinese-women...

Перевести · 27.08.2016 · There’s one big reason for this: tampons are incredibly rare in China– only 2% of Chinese women use them; in Europe, …

https://www.statista.com/topics/4860/women-in-china

Перевести · 17.11.2020 · Consequently, China is currently one of the rare countries in the world with more men than women. According to official estimates of 2019, the surplus of men among …

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_China

Maternal mortality (per 100,000): 37 (2010)

Women in labour force: 67.7% (2011)

Women in parliament: 24.2% (2013)

Women over 25 with secondary education: 54.8% (2010)

Older Chinese traditions surrounding marriage included many ritualistic steps. During the Han Dynasty, a marriage lacking a dowry or betrothal gift was seen as dishonorable. Only after gifts were exchanged would a marriage proceed; and the bride would be taken to live in the ancestral home of the new husband. Here, a wife was expected to live with the entirety of her husband's family and to follow all of their rules and beliefs. Many families followed the Confucianteachings r…

Older Chinese traditions surrounding marriage included many ritualistic steps. During the Han Dynasty, a marriage lacking a dowry or betrothal gift was seen as dishonorable. Only after gifts were exchanged would a marriage proceed; and the bride would be taken to live in the ancestral home of the new husband. Here, a wife was expected to live with the entirety of her husband's family and to follow all of their rules and beliefs. Many families followed the Confucian teachings regarding honoring their elders. These rituals were passed down from father to son. Official family lists were compiled, containing the names of all the sons and wives. Brides who did not produce a son were written out of family lists. When a husband died, the bride was seen as the property of her spouse's family. Ransoms were set by some brides' families to get their daughters back, though never with her children, who remained with her husband's family.

John Engel, a professor of Family Resources at the University of Hawaii, argues that the People's Republic of China established the Marriage Law of 1950 to redistribute wealth and achieve a classless society. The law "was intended to cause ... fundamental changes ... aimed at family revolution by destroying all former patterns ... and building up new relationships on the basis of the new law and new ethics." Xiaorong Li, a researcher at the Institute for Philosophy and Public Policy at the University of Maryland, asserts that the Marriage Law of 1950 not only banned the most extreme forms of female subordination and oppression, but gave women the right to make their own marital decisions. The Marriage Law specifically prohibited concubinage and marriages when one party was sexually powerless, suffered from a venereal disease, leprosy, or a mental disorder. Several decades after the implementation of the 1950 Marriage Law, China still faces serious issues, particularly in population control.

In a continuing effort to control marriage and family life, a marriage law was passed in 1980 and enacted in 1981. This New Marriage Law banned arranged and forced marriages and shifted the focus away from the dominance of men and onto the interests of children and women. Article 2 of the 1980 Marriage Law directly states: "the lawful rights and interests of women, children and the aged are protected. Family planning is practiced." Adults, both men and women, also gained the right to lawful divorce.

To fight the tenacity of tradition, Article 3 of the 1980 Marriage Law continued to ban concubinage, polygamy, and bigamy. The article forbade mercenary marriages in which a bride price or dowry is paid. According to Li, the traditional business of selling women in exchange for marriage returned after the law gave women the right to select their husbands. In 1990, 18,692 cases were investigated by Chinese authorities.

Although the law generally prohibited the exaction of money or gifts in connection with marriage arrangements, bride price payments are still common in rural areas, though dowries have become smaller and less common. In urban areas the dowry custom has nearly disappeared. The bride price custom has since transformed into providing gifts for the bride or her family. Article 4 of the 1980 marriage law banned the usage of compulsion or the interference of third parties, stating: "marriage must be based upon the complete willingness of the two parties." As Engel argues, the law also encouraged gender equality by making daughters just as valuable as sons, particularly in the potential for old-age insurance. Article 8 states: "after a marriage has been registered, the woman may become a member of the man's family, or the man may become a member of the woman's family, according to the agreed wishes of the two parties."

More recently there has been a surge in Chinese–foreigner marriages in mainland China—more commonly involving Chinese women than Chinese men. In 2010, almost 40,000 women registered in Chinese–foreigner marriages in mainland China. In comparison, fewer than 12,000 men registered these types of marriages in the same year.

Second wives

In traditional China, polygamy was legal and having a concubine (see concubinage) was considered a luxury for aristocratic families. In 1950, polygamy was outlawed, but the phenomenon of de facto polygamy, or so-called "second wives" (二奶 èrnǎi in Chinese), has reemerged in recent years. When polygamy was legal, women were more tolerant of their husband's extramarital affairs. Today, women who discover that their husband has a "second wife" are less tolerant, and since the New Marriage Law of 1950 can ask for a divorce.

The sudden industrialization in China brought two types of people together: young female workers and rich businessmen from cities like Hong Kong. A number of rich businessmen are attracted to these economically dependent women and started relationships known as "keeping a second wife" (bao yinai) in Cantonese. Some migrant women who struggle to find husbands become second wives and lovers. There are many villages in the southern part of China where predominantly these "second wives" live. The men come and spend a large amount of time in these villages every year while their first wife and family stay in the city. The relationships can range from just being casual paid sexual transactions to long-term relationships. If a relationship does develop more, some of the Chinese women quit their job and become 'live-in lovers' whose main job is to please the working man.

The first wives in these situations have a hard time and deal with it in different ways. Women that are far away from their husbands do not have many options. Even if the wives do move to mainland China with their husbands, the businessman still finds ways to carry on affairs. Some wives follow the motto "one eye open, with the other eye closed" meaning they understand their husbands are bound to cheat but want to make sure they practice safe sex and do not bring home other children. Many first wives downplay the father's role to try to address the children's questions about a father that is often absent. Other women fear for their financial situations and protect their rights by putting the house and other major assets in their own names.

This situation has created many social and legal issues. Unlike previous generations of arranged marriages, the modern polygamy is more often voluntary. Women in China face serious pressures to be married, by family and friends. There is a derogatory term for women who are not married by the time they are in their late twenties, sheng nu. With these pressures to be married, some women who have few prospects willingly enter into a second marriage. Sometimes these women are completely unaware that the man was already married. Second wives are often poor and uneducated and are attracted by promises of a good life, but can end up with very little if a relationship ends.[5] There are lawyers who specialize in representing "second wives" in these situations. The documentary, "China's Second Wives"[6] takes a look at the rights of second wives and some of the issues they face.

Policies on divorce

The Marriage Law of 1950 empowered women to initiate divorce proceedings. According to Elaine Jeffreys, an Australian Research Council Future Fellow and Associate Professor in China studies, divorce requests were only granted if they were justified by politically proper reasons. These requests were mediated by party-affiliated organizations, rather than accredited legal systems. Ralph Haughwout Folsom, a professor of Chinese law, international trade, and international business transactions at the University of San Diego, and John H. Minan, a trial attorney in the Civil Division of the U.S. Department of Justice and a law professor at the University of San Diego, argue that the Marriage Law of 1950 allowed for much flexibility in the refusal of divorce when only one party sought it. During the market-based economic reforms, China re-instituted a formal legal system and implemented provisions for divorce on a more individualized basis.

Jeffreys asserts that the Marriage Law of 1980 provided for divorce on the basis that emotions or mutual affections were broken. As a result of the more liberal grounds for divorce, the divorce rates soared As women began divorcing their husbands tensions increased and men resisted, especially in rural areas . Although divorce was now legally recognized, thousands of women lost their lives for attempting to divorce their husbands and some committed suicide when the right to divorce was withheld. Divorce, once seen as a rare act during the Mao era (1949–1976), has become more common with rates continuing to increase. Along with this increase in divorce, it became evident that divorced women were often given an unfair share or housing and property.

The amended Marriage Law of 2001, which according to Jeffreys was designed to protect women's rights, provided a solution to this problem by reverting to a "moralistic fault-based system with a renewed focus on collectivist mechanisms to protect marriage and family." Although all property acquired during a marriage was seen as jointly-held, it was not until the implementation of Article 46 of the 2001 Marriage Law that the concealment of joint property was punishable. This was enacted to ensure a fair division during a divorce. The article also granted the right for a party to request compensation from a spouse who committed illegal cohabitation, bigamy, and family violence or desertion.

Domestic violence

In 2004, the All-China Women's Federation compiled survey results to show that thirty percent of families in China experienced domestic violence, with 16 percent of men having beaten their wives. In 2003, the percentage of women domestically abusing men increased, with 10 percent of familial violence involving male victims. The Chinese Marriage Law was amended in 2001 to offer mediation services and compensation to those who were subjected to domestic violence. Domestic violence was finally criminalized with the 2005 amendment of the Law of Protection of Rights and Interests of Women. However, the lack of public awareness of the 2005 amendment has allowed spousal abuse to persist.

Education

Males are more likely to be enrolled than females at every age group in China, further increasing the gender gap seen in schools among older age groups. Female primary and secondary school enrollment suffered more than male enrollment during the Great Chinese Famine (1958–1961), and in 1961 there was a further sudden decrease. Although the gender gap for primary and secondary education has narrowed over time, gender disparity persists for tertiary institutions.

The One Percent Population Survey in 1987 found that in rural areas, 48 percent of males aged 45 and above and 6 percent of males aged 15–19 were illiterate. Although the percentage of illiterate women decreased significantly from 88 percent to 15 percent, it is significantly higher than the percentage of illiterate men for the same age groupings.

Health care

In traditional Chinese culture, which was a patriarchal society based on Confucian ideology, the healthcare system was tailored for men, and women were not prioritized.

Chinese health care has since undergone much reform and has tried to provide men and women with equal health care. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the People's Republic of China began to focus on the provision of health care for women. This change was apparent when the women in the workforce were granted health care. Health care policy required all women workers to receive urinalysis and vaginal examinations yearly. The People's Republic of China has enacted various laws to protect the health care rights of women, including the Maternal and Child Care law. This law and numerous others focus on protecting the rights of all women in the People's Republic of China.

For women in China, the most common type of cancer is cervical cancer. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests using routine screening to detect cervical cancer. However, information on cervical cancer screening is not widely available for women in China.

Ethnic and religious minorities

After the founding of People's Republic of China in 1949, the communist government authorities called traditional Muslim customs on women “backwards or feudal”.

Hui Muslim women have internalized the concept of gender equality because they view themselves as not just Muslims but Chinese citizens, so they have the right to exercise rights like initiating divorce.

A unique feature of Islam in China is the presence of female-only mosques. Women in China can act as prayer leaders and also become imams. Female-only mosques grant women more power over religious affairs. This is rare by global standards. By comparison, the first women's mosque in the United States didn't open until January 2015.

Among the Hui people (but not other Muslim ethnic minorities such as the Uyghurs) Quranic schools for girls evolved into woman-only mosques and women acted as imams as early as 1820. These imams are known as nü ahong (女阿訇), i.e. "female akhoond", and they guide female Muslims in worship and prayer.

Due to Beijing having tight control over religious practices, Chinese Muslims are isolated from trends of radical Islam which emerged after the 1979 Iranian Revolution. According to Dr Khaled Abou El Fadl from the University of California in Los Angeles, this explains the situation whereby female imams, an ancient tradition long ended elsewhere, continue to exist in China.

Among Uyghurs, it was believed that God designed women to endure hardship and work. The word for "helpless one", ʿājiza, was used for women who were not married, while women who were married were called mazlūm among in Xinjiang; however, divorce and remarriage was facile for the women. The modern Uyghur dialect in Turfan uses the Arabic word for oppressed, maẓlum, to refer to "married old woman" and pronounce it as mäzim. Women were normally referred to as "oppressed person" (mazlum-kishi). 13 or 12 years old was the age of marriage for women in Khotan, Yarkand, and Kashgar.

During the last years of imperial China, Swedish Christian missionaries observed the oppressive conditions for Uyghur Muslim women in Xinjiang during their stay between 1892-1938. Uyghur Muslim women were oppressed and of

Darryl Hannah Ass Worship Porno

Hentai Manga Anal Enema

Private Matador 5 Sex Trip

Lesbian Domination Humiliation

Femdom Anal Licking

Rare Vintage Photographs of Chinese Women From Betwee…

Rare Photographs of Chinese Women from the 1800s

Characteristics all Traditional Chinese Women Have ...

Rare Chinese Woman for SALE, BEST Offer & Auction | Bath ...

Bound To Be Beautiful: 30 Scary Vintage Photos of Chinese ...

Why Chinese women don't use tampons | Women | The Guardian

Women in China - Wikipedia

100 Most Unique And Beautiful Chinese Names For Girls ...

Chinese Women at ChinaLoveCupid.com

Rare Of Chinese Women

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)