Private Organization

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Raymond L. Smith, ... Michael A. Gonzalez, in Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, 2014

While both private organizations and the public are asking for increased attention to sustainability (economic, environmental, and social aspects), the amount of information available on the topic continues to expand. People from many fields, for instance accountants and related business professionals, are also getting involved. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB, 2013) looks for evidence of interest and financial impact in establishing the materiality of sustainability issues. Sustainable “materiality” can be defined as sustainability information which when omitted misleads investors about expectations of a company (IRI, 2012). These accounting impacts can be direct (e.g., scarcity of resources) or indirect, when consumer, NGO, or other groups could affect company performance (SASB, 2013). The Initiative for Responsible Investment (2012) points out that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has a number of social and environmental disclosure requirements which apply whether or not there is an immediate impact on financial results. This expansion beyond financial results is the focus of such groups as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI, 2013), whose G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines help organizations measure performance, with the intent that sustainability performance disclosure leads to increasing sustainability.

Increasing sustainability can be approached by other means, including through the education of those who design, construct, and operate facilities. When the facilities of interest are manufacturing processes, then introducing sustainability into the engineering curricula helps satisfy the need. In addition, learning about sustainability simultaneously along with conventional process system engineering (PSE) knowledge will help students to incorporate sustainability with PSE at early education stages rather than just as an add-on during their professional careers. Sustainability in the engineering curricula has been the subject of recent interest (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2013), where objectives (i.e., desired results) are put forth as well as principles for achieving them (e.g., using systems thinking). When the function of a facility is the production of chemical products, the substantial need for sustainability education falls upon chemical engineers. As Allen and Shonnard (2012) state, there is a new need in chemical engineering to systematically address sustainability at multiple scales in a global setting with multiple objectives. They further suggest three elements are needed to educate chemical engineers: framing challenges to put sustainability into context, considering multiple system-level perspectives, and assessing and designing for sustainability.

The final element, assessing and designing for sustainability, demonstrates the need for tools and methodologies that are capable of providing an assessment and informing of design needs which consider and implement aspects of sustainability. In this work, an opportunity for addressing this needed element in chemical engineering education is suggested. This evaluation technique is based on the EPA’s GREENSCOPE methodology and its tool application for designing more sustainable processes.

Fig. (1) describes a framework for a methodology to connect a set of sustainability assessment approaches with different levels (multiple-system levels) and actions relative to the performance impact of product manufacturing. The GREENSCOPE portion represents a gate-to-gate sustainability evaluation and quantifies the contribution the facility provides to the next higher level of sustainability evaluation, a life cycle assessment (LCA) of the chemical product (and supply chain). Finally, the next higher level, Eco-LCA, encompasses sustainable system indicators which represent the interaction of the chemical facility and its inputs and outputs with the surrounding ecosystem. This approach demonstrates the domino effect alterations at the process level can have on the entire ecosystem, and by applying sustainability assessment and design tools significant improvements to the entire ecosystem can be realized.

Figure 1. Framework for multiple-system level sustainability assessments based on characteristics of a chemical production facility and product.

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444634337501085

As explained in Chapter 3, a number of private organizations assist public and private sector efforts at security, safety, and fire protection. This assistance is through research, standards, and publications. Examples of these private organizations include NFPA and UL. Another related private organization is Factory Mutual Global. This organization works to improve the effectiveness of fire protection systems and new fire suppression chemicals, as well as cost evaluation of fire protection systems. It tests materials and equipment submitted by manufacturers. An approval guide is published, and like UL, it issues labels to indicate that specific products have passed its tests.

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123878465000139

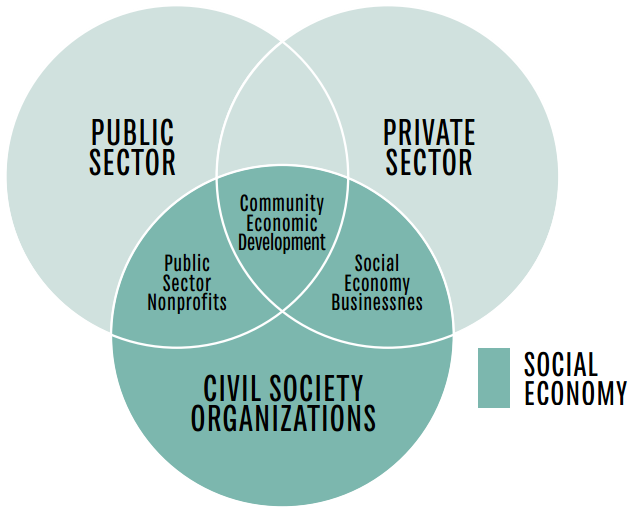

Environmental planning embraces those activities of government agencies and private organizations whose primary purpose is to manage the impacts of human development and use of land on the natural environment, by taking thought for the future and choosing courses of action that promote appropriate goals. It is closely integrated with environmental pollution control, and is an integral component of the management of urban development and redevelopment. Societies have engaged in some form of environmental planning for millennia, but the field has expanded dramatically in the last 30 years, as scientists and legislators have come to understand the seriousness and magnitude of impact of humankind on the natural world.

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0080430767044442

Tomas Lidman, in Libraries and Archives, 2012

There is no general agreement as to the nature of a modern archive. Thus it should not come as any surprise that professional archivists and the users of archives have difficulty agreeing upon a definition of archives. The one used by the ICA (International Council on Archives) is very broad and inclusive, thus easy to accept. Bradsher, without belying his North American background and making use of this general definition, states that:

archives are the official or organised records of governments, public and private institution and organisations, groups of people and individuals, whatever their date, form and material appearance, preserved, either as evidence of origins, structure, function, and activities or because of the value of the information they contain, whether or not they have been transferred to an archival institution.

Less elegant in style and approach, the Swedish archivist Nils Nilsson had claimed that:

the primary mission of archives is to preserve and provide access to archival collections and primary sources, regardless of their condition and their age. Recent documents are just as indispensable as historically significant sources. Additionally, archives should provide the necessary service for the scholarly community, administrative agencies and society at large. An archive is a collection of documents which furnishes evidence about and reflects the activity of its creator.

Dutch archival theory, as it was codified and standardised in the manual of 1898, claimed that:

an archival collection is the whole of the written documents, drawings and printed materials, officially received or produced by an administrative body or one of its officials, in so far as these documents were intended to remain in the custody of that body of that official.

Each of these definitions has a different point of reference, but they do share a common denominator. They all agree that archives are intentional in purpose and are construed around the principle that their content must be preserved, systematised, defined and described through their characteristic markers, and made available to potential users. The ICA definition has as its starting point the aims and missions of archives, which are then supplemented by a more practical description of archival structures. The definition is rather general and uncontroversial.

The principle of provenance became the guiding principle of archival theory at the end of the late nineteenth century and radically transformed the organisational structure of archives in Western Europe. Its attractiveness lay in its tri-fold nature: it defined the origin of the material, traced its transfer of ownership and emphasised the sanctity of each collection as a unit. An integral part of this principle was an inherent critique of earlier archival theory and an indisputable emphasis on efficacy. Archives were now viewed as a whole. If previously attention was primarily directed at individual collections, now it underlined the place and role of these individual collections in a larger, often multifarious whole. Archival theory distinguished clearly between archives and collections. A collection could be created by an individual or an institution and have almost any form whatsoever. An archive could be defined by its function or organisation – the only prerequisite was that it had its source in some sort of activity. Nils Nilsson asserted that the adaptation of this principle led to conventions on the nature and essence of the materials and helped coin new meanings for the notion of the archive and its constituent elements – the materials stored. Archival materials were clearly distinguished from other sources, especially books and other printed materials. This, in turn, allowed one to define the ideas which lay at the foundation of archival theory and were implicit in the activity of archivists. From this a methodology could be derived, especially for systematising and documenting the materials. Finally, this theoretical foundation also provided guidelines for how to appraise collections, how to store materials and how to retrieve relevant information (Nilsson, 1977).

I have already directed attention to the developments at the beginning of the twentieth century which transformed how libraries perceived themselves. Of interest for us is the dichotomy which arose between libraries and archives. This dichotomy has been reinforced by varying epistemological ideologies. National libraries were deeply engaged in the search for knowledge. But how was this search to be adapted to a new world in which the object of studies was being construed in new subject categories? Libraries were deeply engaged in finding practical solutions which would adapt the search for knowledge and truth to these new categories. At the same time, national libraries had to reaffirm and develop further the whole idea of legal deposit, thus becoming perhaps the most visible champions of open access. Archives, on the other hand, regarded materials as organic units which could not be dispersed or rearranged. A book or a periodical could be extracted from its original context and assigned to a new one, without losing its identity. This stratification could enhance the search for knowledge. It could even assume a completely new identity by being catalogued as a separate item. Archive materials, however, were to be viewed as belonging to a unit and thus also derived their identity from it. Perhaps oversimplifying a little, we could claim that the library had to guarantee free access to all information, even its most basic constituent element. If in the library world one looked at the collection from the outside in, the archive reveals what makes an item that which it is, by underscoring its place in a larger structure.

The archive must work in conjunction with those institutions providing material, be they public or private, and devise methods of compounding the material in a way which most accurately reflects the activity of the institution. This is an ongoing process due to the dynamic nature of human society, which is never stationary. A good example of this dynamic quality is the recent transition to electronic platforms, which have altered not only the form in which material is transferred and its organisational structure, but even its essence, attributes and modality. As a result, archives have become much more involved in the process of creating archives and determining how material will be stored, as well as with the legal aspects of documenting a society. The integrity of the individuals and institutions which make up this society must be protected without jeopardising the right of the individual to retain free access to this material. This has resulted in a rather peculiar set of circumstances. Safeguarding the rights of individuals, while documenting societal development, has proved to be an expensive proposition. Archives have had trouble processing, preserving and providing access to these vast materials.

Simultaneously, not all materials can and should be preserved indefinitely. Some limits should be imposed. With the expansion of administrative structures, the sheer volume of materials is overwhelming. This was not as pressing a problem previously. But for modern societies with large administrative infrastructures, this problem can be alleviated only by appraisal. Appraisal requires its own policy and procedures.

Archives are also unique since they are called upon to keep in store for future use even classified materials under strict confidence. These can be of a political nature or deal with security issues. But most sensitive is usually private confidentiality. Private confidentiality agreements guarantee that materials are stored, but not released for significant periods of time. Once they are released, there may be careful regulations about who is permitted to access them – for example, family members or serious scholars. Administering confidentiality has become an ever-increasing burden for archives since the number of electronic registers has increased to a manifold degree with the digital revolution. There does not appear to be any end to the collection of structured data in computer storage. Confidentiality is an issue with which archives must deal on a daily basis. It may be necessary to decide what is really confidential and what is not; it may be necessary to determine who should have access to what. Any transgression in this area can be financially and legally punitive. Libraries are seldom compelled to engage these issues. When it happens, it is often a result of sensitive private collections which cannot be opened for a set time or documents, periodicals, etc. which contain materials which are morally objectionable or politically ‘hot stuff’.

The need for international standards and principles for library materials has been self-evident. Archival materials must be processed differently, due to their unique nature. For this reason, less attention has been paid to principles of standardisation. But even in this area, significant steps have been taken in conjunction with the ISO (International Organization for Standardization). The greatest effort has been expended in creating standards for digital materials – for electronically delivered materials from both governmental and private agencies as well as more general digital content. Due to the reasons mentioned above, archives have not made use of technical aids to the same degree as libraries.

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978184334642550005X

Cyber-terrorism is common nowadays. There is a complex network of private and public organizations used in supervising the Internet. Even so, the complexity of the system is leading to an increase in the response time due to various bottlenecks in relation to information flow. As a result, a paradigm shift in security auditing in cyberspace is required. An approach based on intelligent agents may decrease the time needed to gather and process the basic information. A multi-agent system with the goal of helping the user, the security expert, and the security officer is presented in this chapter. The system will process local knowledge databases as well as external information provided by social networks, news feeds, and other forms of published information available on the Internet. An executive summary will be automatically generated and presented to the security chief of the organization using the system. Also, the system may provide advice to ordinary users when disputable decisions regarding computing node security must be made.

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124114746000268

Gabriella von Rosing, ... Henrik von Scheel, in The Complete Business Process Handbook, 2015

Strong social and business demand for wide sustainability creates a scenario in which organizations, public and private, feel more pressure to improve in sustainability performance to achieve:

Cost efficiencies, in which eco-efficiency is taking an increasing role as it delivers a reduction in raw materials and energy consumption, in greenhouse and other taxed emissions and waste

Easier accommodation to stricter environmental standards and regulations, whether governmental or voluntary

Exploitation of business opportunities in the form of new products and services or new revenue streams brought about by the monetization of emission rights, sale of by-products, or license of know-how on sustainability. Here, we can find some new products and services such as electric and hybrid cars, renewable energy projects, and smart grids and cities

Radical transformation of those business models most affected by sustainability concerns, such as logistics, oil, power, mining, and forest products, among others

Improved reputation as well as proactive response to customer and stakeholder requirements of environmental- and community-friendly products, services, and processes

Currently, there are several approaches to environmental and social responsibility (ISO 14,001, EMAS (Eco-Management and Audit Scheme), GRI (Global Reporting Initiative), ISO 26,000, etc.). Unfortunately, their focus is narrow because they seek only specific aspects of sustainability in organizations, addressing areas such as reporting, communication of impacts to stakeholders, process controls, compliance, or performance improvement, but typically only an environmental or social context. When any of these approaches takes on the larger view, it is at best addressed in a partial and restricted way. Then, wider opportunities for sustainable value creation remain mostly untouched because of a lack of integration of those considerations in the organization’s (or indeed, the enterprise’s) overall operations.

URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012799959300024

Skinny Russian Blondes

Sex Rough Fuck

Cute Anal Fuck

Piss Teen Pee

Female Form

Private Organization | UpCounsel 2020

Private Organization - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

Private organization definition - Law Insider

Private Organizations - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

Private Organization Law and Legal Definition | USLegal, Inc.

Private Sector Definition

(PDF) Public and Private Organizations: How Different or ...

Privately held company - Wikipedia

Private Organization