Pregnant Prolapse

👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov took too long to respond.

Check any cables and reboot any routers, modems, or other network devices you may be using.

If it is already listed as a program allowed to access the network, try removing it from the list and adding it again.

Check your proxy settings or contact your network administrator to make sure the proxy server is working. If you don't believe you should be using a proxy server:

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov took too long to respond.

Chunyan Zeng, Feng Yang, Chunhua Wu, Junlin Zhu, Xiaoming Guan, Juan Liu, "Uterine Prolapse in Pregnancy: Two Cases Report and Literature Review", Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 2018, Article ID 1805153, 5 pages, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1805153

1Key Laboratory for Major Obstetric Diseases of Guangdong Province, Key Laboratory of Reproduction and Genetics of Guangdong Higher Education Institutes, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, No. 63 Duobao Road, Liwan District, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510150, China

2Department of Ultrasound Medicine, Laboratory of Ultrasound Molecular Imaging, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, No. 63 Duobao Road, Liwan District, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510150, China

3Division of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine, 6651 Main Street, 10th Floor, Houston, Texas 77030, USA

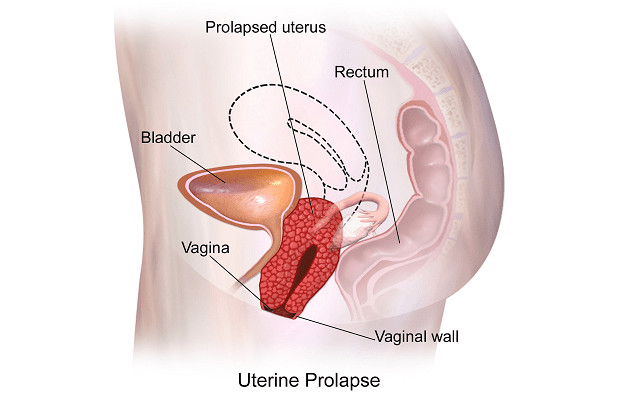

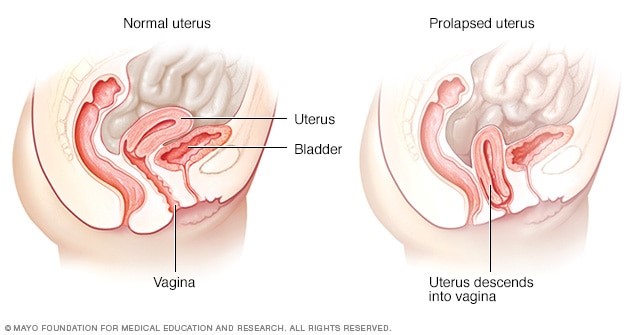

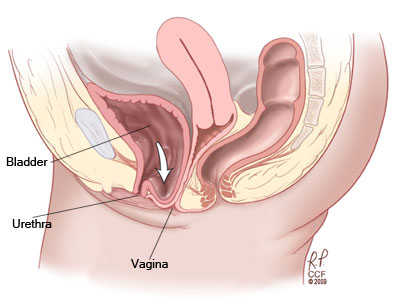

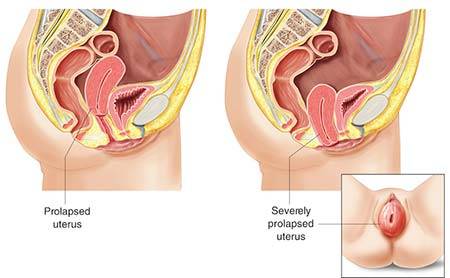

Uterine prolapse complicating pregnancy is rare. Two cases are presented here: one patient had uterine prolapse at both her second and third pregnancy, and the other developed only once prolapse during pregnancy. This report will analyze etiology, clinical characteristics, complication, and treatment of uterine prolapse in pregnancy. Routine gynecologic examination should be carried out during pregnancy. If uterine prolapse occurred, conservative treatment could be used to prolong the gestational period as far as possible. Vaginal delivery is possible, but caesarean section seems a better alternative when prolapsed uterus cannot resolve during childbirth.

A 27-year-old Chinese woman, gravida 3, para 2, body mass index (BMI ) 17.20 kg/m2, visited our clinic with eight-week pregnancy in a prolapsed uterus on of September 2013. Pelvic examination revealed stage 3 pelvic organ prolapse (POP), with point C as the leading edge using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) examination (Aa+3, Ap+3, Ba+6, Bp+6, C+6, D+2, gh 4.5, pb 2, tvl 9 ). Her prolapsed uterus could be restored to pelvic cavity within bed rest. It was more serious while standing or walking. Hospitalization was recommended for this pregnant woman, but she refused and she waited at home for delivery.

Her previous pregnant record was as follows: a dead female baby was induced at the week of gestation during her first vaginal delivery in 2003, puerperium was uneventful, and two days after delivery, she was discharged in good health. She had her second vaginal delivery, after 38+3rd week of gestation and seven-hour labor in 2007; a 2800 g alive baby boy was delivered, with Apgar scores of 10/10. Pelvic examination revealed stage 3 POP using the POPQ examination (Aa+3, Ap+3, Ba+6, Bp+6, C+6, D+2, gh 4.5, pb 2, tvl 9) at the 36+3rd week of gestation in her second pregnancy. No special examination or treatment was executed before and after childbirth. However, the prolapsed vaginal mass was spontaneously restored after childbirth.

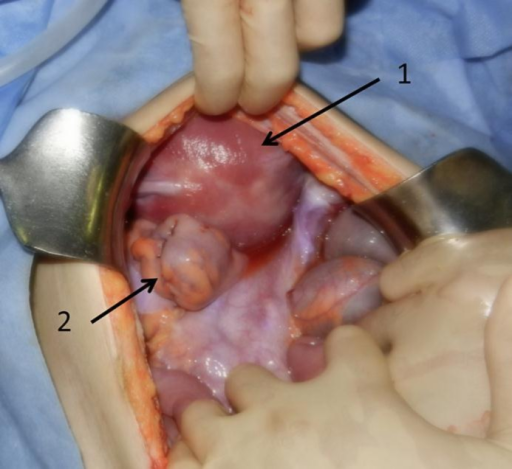

The woman presented to our hospital again with premature rupture of membrane (PROM) in labor at 39+6th week of gestation with an irrestorable uterine prolapse for 8 months on the of May 2014. Pelvic examination revealed stage 4 POP using the POPQ examination (Aa+3, Ap+3, Ba+9, Bp+9, C+9, D+5, gh 4.5, pb 2, tvl 9 ) and it revealed that prolapsed uterus was in size of 20×20 cm, pink, hyperaemic, and edematous but not ulcerated. The cervical canal did not subside, internal orifice of cervix did not open, amnionic vesicle has been broken, and regular contraction was seen. A series of transabdominal ultrasonographic examinations showed a normally developing fetus in the longitudinal position in the uterine cavity, isthmus uteri was 64 mm and it was partially extruded outside the vulva which was protruding from the perineum about 64×68 mm, and the boundary was still clear, and with cervical oedema. Emergency caesarean delivery was decided and an alive boy baby weighting 2480 g, with Apgar scores of 10/10, was delivered. We used Magnesium Sulfate Solution to nurse the prolapsed uterus. Three days postpartum, the prolapsed uterus was in size of 10×10 cm. On the seventh day postpartum, the prolapsed uterus was in size of 7×5 cm, and it was restored inside the pelvic cavity after manual reposition. Pelvic floor three-dimensional ultrasound indicated that residual urine was 40 ml, cervical length was 5.6 cm and internal orifice cervix was dilated, bladder neck displacement was 15 mm, posterior angle of bladder was 180 degree, and hiatus of levator antimuscle was 32 cm2. She was discharged on the eighth days postpartum. A telephone postpartum follow-up on the 14th day showed that there was no lump prolapse when the patient was standing or walking. But when the abdominal pressure increased, such as when squatting and defecating, prolapsed vaginal mass could be palpable, with size of 2 cm × 1 cm. 42 days after childbirth, she refused regular postpartum examinations for personal reasons.

A 33-year-old Chinese woman, gravida 2, para 1, BMI 20.70 kg/m2, noticed a protrusion in size of 2 × 1 cm from her vagina at 13th week of gestation in 2015. Her first pregnancy resulted in one uncomplicated spontaneous vaginal delivery in 2009; the newly-born baby weighted 3000 g. There was neither history of pelvic trauma or prolapse, nor any stress incontinence during or after the first pregnancy.

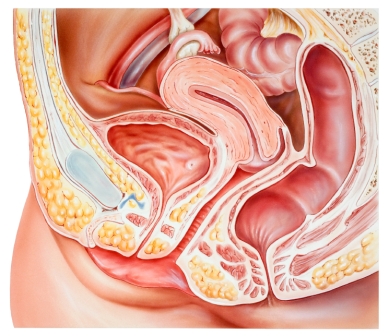

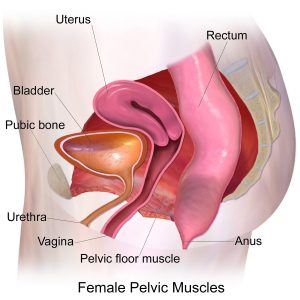

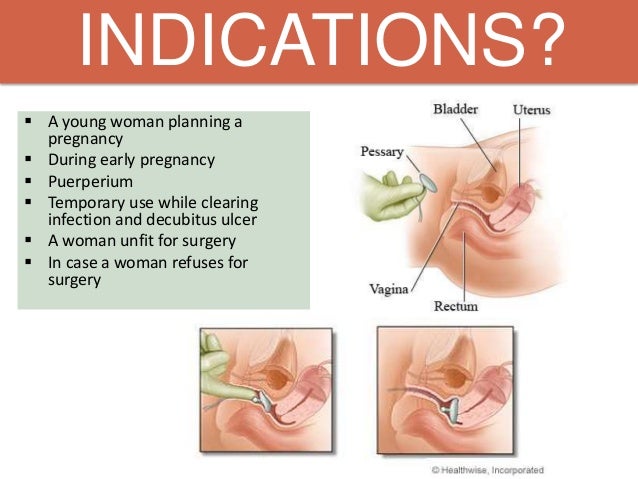

The protrusion was not sensible while resting but rather palpable after moving. She visited our outpatient clinic at her 15th week of gestation in 2015 and complained worsened uterine prolapse. Pelvic examination revealed stage 3 POP, with point C as the leading edge using the POPQ examination (Aa+3, Ap+3, Ba+6, Bp+6, C+6, D+1, gh 5, pb 1, tvl 10 ). A no. 5 ring pessary in size of 7×7 cm (see Figure 1) was applied to keep the uterus inside the pelvic cavity after manual reposition. The gravid uterus persisted in the abdominal cavity after removing at the 30th week of gestation because it became larger. An alive healthy baby boy of 2680 g was delivered after four-hour labor at 39+3 week’s gestation on the of October 2015. She was discharged three days postpartum with complete resolution of the uterine prolapse. A follow-up postpartum examination after 42 days revealed evidence of uterine prolapse and a no. 3 ring pessary in size of 5×5 cm has been applied to keep the uterus inside the pelvic cavity after manual reposition until now. At the time of reporting, pelvic examination of this woman revealed stage 3 POP, with point C as the leading edge using the POPQ examination (Aa-2, Ap-2, Ba-1, Bp-1, C+2, D-3, gh 5, pb 1, tvl 10). Pelvic floor four-dimensional ultrasound indicated that bladder neck mobility was slightly increasing, posterior wall of the bladder was slightly bulged, and anterior vaginal wall was slightly prolapsed in anterior compartment. Stage 2 uterus prolapse was seen in middle compartment, the levator animuscle was not broken, and hiatus of levator animuscle was normal in posterior compartment (see Figure 2). Follow-up is on-going.

Pelvic floor four-dimensional ultrasound of Case 2. Pelvic floor four-dimensional ultrasound indicated that residual urine was 0 ml, thickness of detrusor was normal, internal orifice of urethra was closed, posterior angle of bladder was intact, and there was no dark area of liquid and scattered point of calcification around urethra in quiescent condition. CDFI revealed that sparse color flow signals were seen around the urethra, the bladder neck was 19 mm above the pubic symphysis, the uterus was 17 mm above the pubic symphysis, and ampulla portion of rectum was located at the pubic symphysis. Bladder neck displacement was 15 mm, bladder neck was located 9 mm below the pubic symphysis, posterior angle of bladder was intact, the uterus was 35 mm below the pubic symphysis, ampulla portion of rectum was located at the pubic symphysis, rectocele was not seen, and anal sphincter was complete in Valsalva.

Uterine prolapse is a common case in nonpregnant older women; however, uterine prolapse complicating pregnancy is a rare event, which either exists before or has an acute onset during pregnancy.

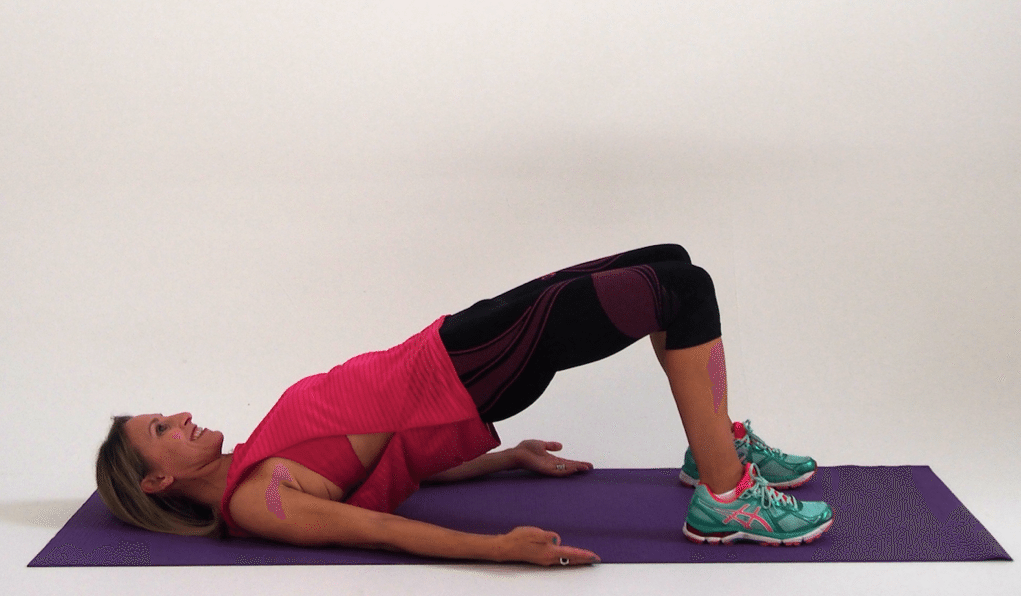

Successful pregnancy outcome requires individualized treatment with respect to patient’s wishes, gestation, and severity of prolapse. Obstetrician should consider the above-mentioned possible complications. The management varies from a conservative approach to laparoscopic treatment. Conservative management with genital hygiene and bed rest in a moderately Trendelenburg position to enable prolapse replacement should be considered as the foremost treatment option. These precautions protect the cervix from trauma desiccation and reduce the incidence of preterm labor. Case 1 had successful pregnancy outcome because of bed rest. This again demonstrated that bed rest in a moderately Trendelenburg position is a practical management strategy.

The method of delivery should be individualized according to the patients’ preferences, status of cervix uteri, and labor progression. A vaginal delivery can be expected. Nonetheless, according to our experience, an elective caesarean section near term could be a valid and safe delivery option when the prolapsed uterus cannot be restored. Patient in Case 2 already had a favorable ripened cervix and the prolapsed uterus has already been in the pelvic cavity when she was referred to our hospital at 39+3 week’s gestation. We did not have to insist on a caesarean section, so the patients ended with vaginal delivery. However, considering cervical dystocia, which results in inability to attain adequate cervical dilatation, in addition to obstructive labor, as well as cervical laceration and a predisposition to rupture of the lower uterine segment, emergency caesarean section was performed to avoid the above-mentioned intrapartum complication in Case 1.

Follow-up is necessary, pelvic floor four-dimensional ultrasound can clearly show the spatial relationship of anterior, middle, and posterior compartments in pelvic cavity, and pelvic examination and pelvic floor four-dimensional ultrasound may be a valid method for follow-up.

Obstetricians as well as all involved caregivers should be aware of this rare phenomenon, as early diagnosis is crucial for a safe gestation. Conservative treatment of these patients throughout pregnancy can lead to an uneventful, normal, spontaneous delivery. Management of uterine prolapse in pregnancy during labor should be individualized depending on the severity of the prolapse, gestational age, parity, and patient’s preference.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81671440). The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

D. De Vita and S. Giordano, “Two successful natural pregnancies in a patient with severe uterine prolapse: A case report,” Journal of Medical Case Reports, vol. 5, p. 459, 2011.

View at: Google Scholar

C. M. Tarnay and C. H. Dorr, Current Obstetric And Gynecology Diagnosis and Treatment, A. H. DeCherney and L. Nathan, Eds., Lange Medical/McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, USA, 2003.

S. A. Obed, “Pelvic Relaxation,” in Comprehensive Gynaecology in the Tropics, E. Y. Kwawukume and E. E. Emuveyan, Eds., pp. 138–146, Science & Education, Accra, Ghana, 2005.

View at: Google Scholar

H. A. Ugboma, A. O. Okpani, and S. E. Anya, “Genital prolapse in Port Harcourt, Nigeria,” Nigerian Journal of Medicine, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 124–129, 2004.

View at: Google Scholar

E. R. Horowitz, Y. Yogev, M. Hod, and B. Kaplan, “Prolapse and elongation of the cervix during pregnancy,” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 77, no. 2, pp. 147-148, 2002.

View at: Publisher Site | Google Scholar

P. S. Hill, “Uterine prolapse complicating pregnancy. A case report,” The Journal of Reproductive Medicine, vol. 29, no. 8, pp. 631–633, 1984.

View at: Google Scholar

H. L. Brown, “Cervical prolapse complicating pregnancy,” Journal of the National Medical Association, vol. 89, pp. 346–348, 1997.

View at: Google Scholar

L. Guariglia, B. Carducci, A. Botta, S. Ferrazzani, and A. Caruso, “Uterine prolapse in pregnancy,” Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 192–194, 2005.

View at: Publisher Site | Google Scholar

A. L. O'Boyle, J. D. O'Boyle, B. Calhoun, and G. D. Davis, “Pelvic organ support in pregnancy and postpartum,” International Urogynecology Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 69–72, 2005.

View at: Publisher Site | Google Scholar

Z. Rusavy, L. Bombieri, and R. M. Freeman, “Procidentia in pregnancy: a systematic review and recommendations for practice,” International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 1103–1109, 2015.

View at: Publisher Site | Google Scholar

B. Cingillioglu, M. Kulhan, and Y. Yildirim, “Extensive uterine prolapse during active labor: A case report,” International Urogynecology Journal, vol. 21, no. 11, pp. 1433-1434, 2010.

View at: Publisher Site | Google Scholar

Y. E. Erata, B. Kilic, S. Güçlü, U. Saygili, and T. Uslu, “Risk factors for pelvic surgery,” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 267, no. 1, pp. 14–18, 2002.

View at: Publisher Site | Google Scholar

P. Tsikouras, A. Dafopoulos, N. Vrachnis et al., “Uterine prolapse in pregnancy: Risk factors, complications and management,” The Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 297–302, 2014.

View at: Publisher Site | Google Scholar

S. Lau and A. Rijhsinghani, “Extensive cervical prolapse duringlabor: a case report,” The Journal of Reproductive Medicine, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 67–69, 2008.

View at: Google Scholar

A. H. Klawans and A. E. Kanter, “Prolapse of the uterus and pregnancy,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 939–946, 1949.

View at: Publisher Site | Google Scholar

P. J. Sulak, “Nonsurgical correction of defects, the use of vaginal support devices,” in Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology, pp. 1082-1083, 8th edition, 1997.

View at: Google Scholar

T. Matsumoto, M. Nishi, M. Yokota, and M. Ito, “Laparoscopic treatment of uterine prolapse during pregnancy,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 93, no. 5, p. 849, 1999.

View at: Publisher Site | Google Scholar

Copyright © 2018 Chunyan Zeng et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Cookies Settings Accept All Cookies

Britney Amber Nipples

King Of The Hill Xxx Parody

100 Natural Latex

Scream Xxx Parody

12 Years Old Sex Video

Uterine prolapse in pregnancy: risk factors, complications ...

Uterine Prolapse in Pregnancy: Two Cases Report and ...

Uterine Prolapse In Pregnancy: Signs, Causes And Treatment

Mitral valve prolapse and pregnancy - PubMed

What Are the Concerns of Prolapse in Pregnancy? (with ...

Pregnant with a Prolapse — Elemental Chiropractic

I Completely Cured My Prolapsed Uterus While Pregnant ...

Pregnant Prolapse