Philip K Dick S

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

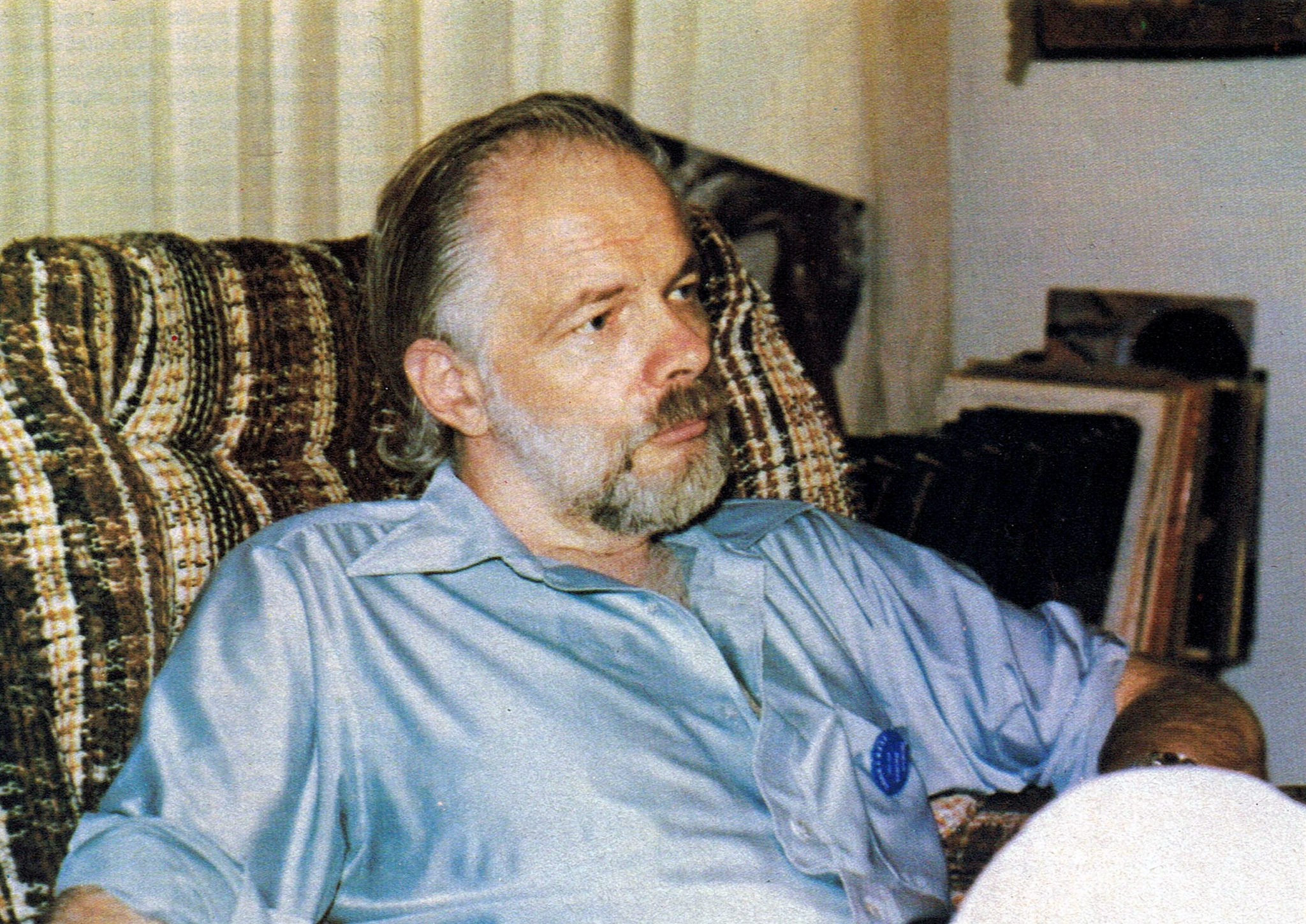

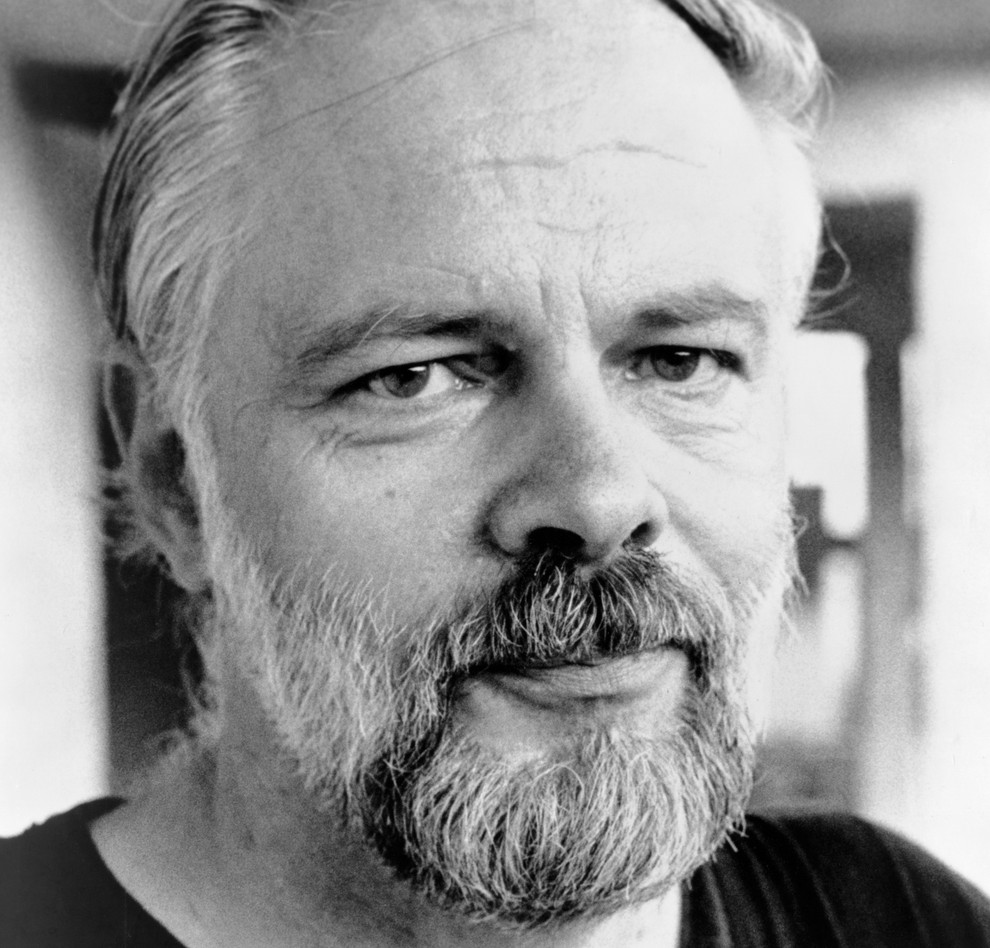

Philip Kindred Dick (December 16, 1928 – March 2, 1982) was an American science fiction writer. He wrote 44 novels and about 121 short stories, most of which appeared in science fiction magazines during his lifetime.[1] His fiction explored varied philosophical and social themes, and featured recurrent elements such as alternate realities, simulacra, monopolistic corporations, drug abuse, authoritarian governments, and altered states of consciousness, and often explored topics such as the nature of reality, perception, human nature, and identity.[2]

Philip Kindred Dick

December 16, 1928

Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

March 2, 1982 (aged 53)

Santa Ana, California, U.S.

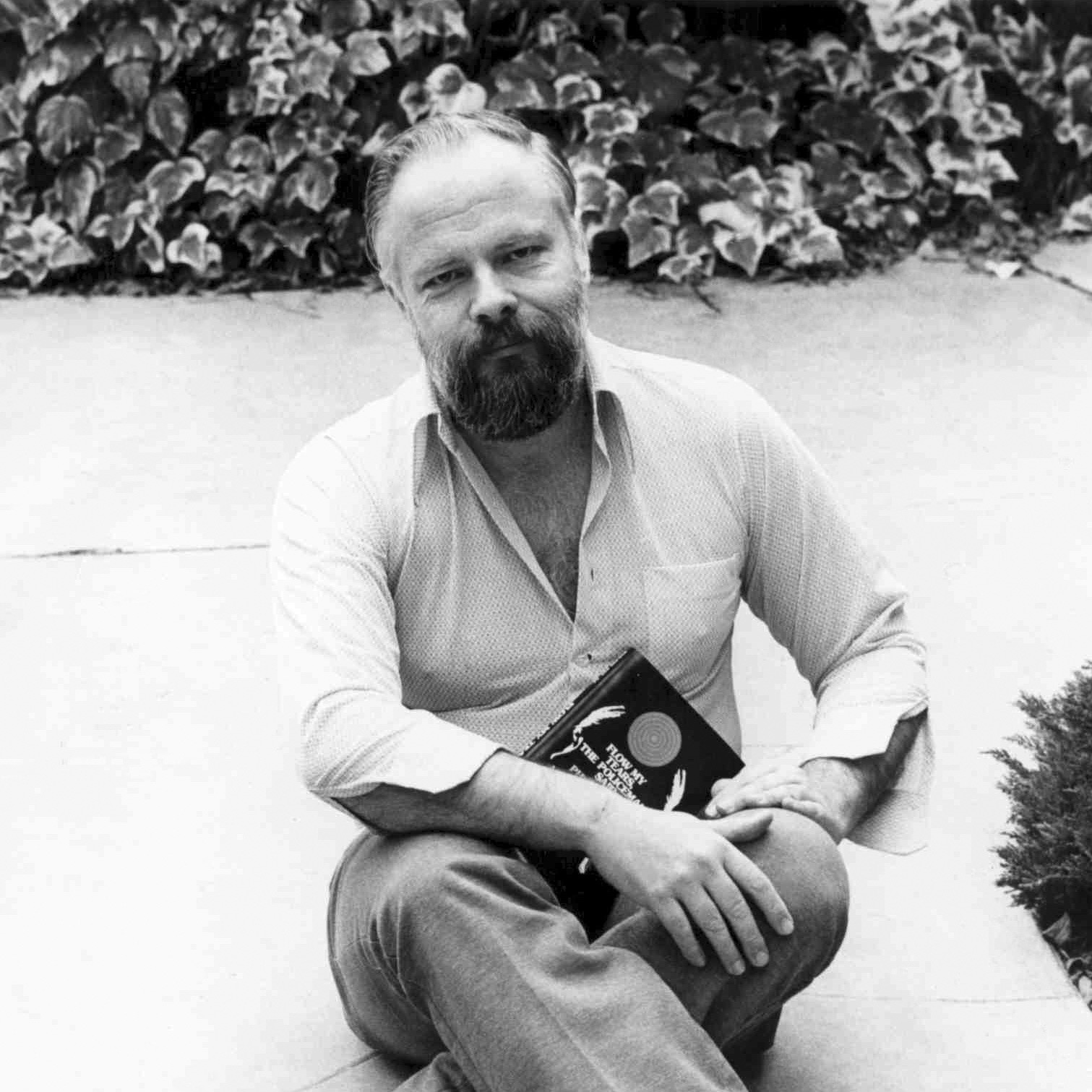

Writer: novelist, short story writer, and essayist

Born in Chicago, Dick moved to the San Francisco Bay Area with his family at a young age. He began publishing science fiction stories in 1952, at age 23. He found little commercial success[3] until his alternative history novel The Man in the High Castle (1962) earned him acclaim, including a Hugo Award for Best Novel, when he was 33.[4] He followed with science fiction novels such as Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) and Ubik (1969). His 1974 novel Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel.[5]

Following a series of religious experiences in 1974, Dick's work engaged more explicitly with issues of theology, metaphysics, and the nature of reality, as in novels A Scanner Darkly (1977) and VALIS (1981).[6] A collection of his speculative nonfiction writing on these themes was published posthumously as The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick (2011). He died in 1982 in Santa Ana, California, at the age of 53, due to complications from a stroke.[citation needed]

Dick's posthumous influence has been widespread, extending beyond literary circles into Hollywood filmmaking.[7] Popular films based on his works include Blade Runner (1982), Total Recall (adapted twice: in 1990 and in 2012), Minority Report (2002), A Scanner Darkly (2006), and The Adjustment Bureau (2011). Beginning in 2015, Amazon produced the multi-season television adaptation The Man in the High Castle, based on Dick's 1962 novel; and in 2017 Channel 4 began producing the ongoing anthology series Electric Dreams, based on various Dick stories. In 2005, Time magazine named Ubik (1969) one of the hundred greatest English-language novels published since 1923.[8] In 2007, Dick became the first science fiction writer included in The Library of America series.[9][10][11]

Dick and his twin sister, Jane Charlotte Dick, were born six weeks prematurely on December 16, 1928, in Chicago, Illinois, to Dorothy (née Kindred; 1900–1978) and Joseph Edgar Dick (1899–1985), who worked for the United States Department of Agriculture.[12][13] His paternal grandparents were Irish.[14] Jane's death on January 26, 1929, six weeks after their birth, profoundly affected Philip's life, leading to the recurrent motif of the "phantom twin" in his books.[12]

Dick's family later moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. When he was five, his father was transferred to Reno, Nevada, and when Dorothy refused to move, she and Joseph divorced. Both fought for custody of Philip, which was awarded to Dorothy. Determined to raise Philip alone, she took a job in Washington, DC and moved there with her son. Philip was enrolled at John Eaton Elementary School (1936–1938), completing the second through fourth grades. His lowest grade was a "C" in Written Composition, although a teacher said he "shows interest and ability in story telling". He was educated in Quaker schools.[15] In June 1938, Dorothy and Philip returned to California, and it was around this time that he became interested in science fiction.[16] Dick stated that he read his first science fiction magazine, Stirring Science Stories, in 1940.[16]

Dick attended Berkeley High School in Berkeley, California. He and fellow science fiction author Ursula K. Le Guin were members of the class of 1947 but did not know each other at the time. After graduation, he attended the University of California, Berkeley from September 1949 to November 11, 1949, ultimately receiving an honorable dismissal dated January 1, 1950. He did not declare a major and took classes in history, psychology, philosophy, and zoology. Through his studies in philosophy, he believed that existence is based on internal human perception, which does not necessarily correspond to external reality. He described himself as "an acosmic panentheist," believing in the universe only as an extension of God.[17] After reading the works of Plato and pondering the possibilities of metaphysical realms, he came to the conclusion that, in a certain sense, the world is not entirely real and there is no way to confirm whether it is truly there. This question from his early studies persisted as a theme in many of his novels. Dick dropped out because of ongoing anxiety problems, according to his third wife Anne's memoir. She also says he disliked the mandatory ROTC training. At Berkeley, he befriended poet Robert Duncan and poet and linguist Jack Spicer, who gave Dick ideas for a Martian language. Dick claimed to have hosted a classical music program on KSMO Radio in 1947.[18] From 1948 to 1952, he worked at Art Music Company, a record store on Telegraph Avenue.

Dick sold his first story, "Roog", in 1951, when he was 22, about "a dog who imagined that the garbagemen who came every Friday morning were stealing valuable food which the family had carefully stored away in a safe metal container".[19] From then on he wrote full-time. During 1952, his first speculative fiction publications appeared in July and September numbers of Planet Stories, edited by Jack O'Sullivan, and in If and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction that year.[20] His debut novel, Solar Lottery, was published in 1955 as half of Ace Double #D-103 alongside The Big Jump by Leigh Brackett.[20] The 1950s were a difficult and impoverished time for Dick, who once lamented, "We couldn't even pay the late fees on a library book." He published almost exclusively within the science fiction genre, but dreamed of a career in mainstream fiction.[21] During the 1950s, he produced a series of non-genre, relatively conventional novels.[22]

In 1960, Dick wrote that he was willing to "take twenty to thirty years to succeed as a literary writer". The dream of mainstream success formally died in January 1963 when the Scott Meredith Literary Agency returned all of his unsold mainstream novels. Only one of them, Confessions of a Crap Artist, was published during Dick's lifetime.[citation needed]

In 1963 Dick won the Hugo Award for The Man in the High Castle.[4] Although he was hailed as a genius in the science fiction world, the mainstream literary world was unappreciative, and he could publish books only through low-paying science fiction publishers such as Ace. Even in his later years, he continued to have financial troubles. In the introduction to the 1980 short story collection The Golden Man, he wrote:

"Several years ago, when I was ill, Heinlein offered his help, anything he could do, and we had never met; he would phone me to cheer me up and see how I was doing. He wanted to buy me an electric typewriter, God bless him—one of the few true gentlemen in this world. I don't agree with any ideas he puts forth in his writing, but that is neither here nor there. One time when I owed the IRS a lot of money and couldn't raise it, Heinlein loaned the money to me. I think a great deal of him and his wife; I dedicated a book to them in appreciation. Robert Heinlein is a fine-looking man, very impressive and very military in stance; you can tell he has a military background, even to the haircut. He knows I'm a flipped-out freak and still he helped me and my wife when we were in trouble. That is the best in humanity, there; that is who and what I love."[citation needed]

In 1971, Dick's marriage to Nancy Hackett broke down, and she moved out of their house in Santa Venetia, California. He had abused amphetamine for much of the previous decade, stemming in part from his need to maintain a prolific writing regimen due to the financial exigencies of the science fiction field. He allowed other drug users to move into the house. Following the release of 21 novels between 1960 and 1970, these developments were exacerbated by unprecedented periods of writer's block, with Dick ultimately failing to publish new fiction until 1974.[23]

One day, in November 1971, Dick returned to his home to discover it had been burglarized, with his safe blown open and personal papers missing. The police couldn't determine the culprit, and even suspected Dick of having done it himself.[24] Shortly thereafter, he was invited to be guest of honor at the Vancouver Science Fiction Convention in February 1972. Within a day of arriving at the conference and giving his speech, The Android and the Human, he informed people that he had fallen in love with a woman named Janis whom he had met there and announced that he would be remaining in Vancouver.[24] An conference attendee, Michael Walsh, movie critic for the local newspaper The Province, invited Dick to stay in his home, but asked him to leave two weeks later due to his erratic behavior. Janis then ended their relationship and moved away. On March 23, 1972, Dick attempted suicide by taking an overdose of the sedative potassium bromide.[24] Subsequently, after deciding to seek help, Dick became a participant in X-Kalay (a Canadian Synanon-type recovery program), and was well enough by April to return to California.[24]

On relocating to Orange County, California at the behest of California State University, Fullerton professor Willis McNelly (who initiated a correspondence with Dick during his X-Kalay stint), he donated manuscripts, papers and other materials to the University's Special Collections Library, where they are in the Philip K. Dick Science Fiction Collection in the Pollak Library. During this period, Dick befriended a circle of Fullerton State students that included several aspiring science fiction writers, including K. W. Jeter, James Blaylock and Tim Powers. Jeter would later continue Dick's Bladerunner series with three sequels.[citation needed]

Dick returned to the events of these months while writing his novel A Scanner Darkly (1977),[25] which contains fictionalized depictions of the burglary of his home, his time using amphetamines and living with addicts, and his experiences of X-Kalay (portrayed in the novel as "New-Path"). A factual account of his recovery program participation was portrayed in his posthumously released book The Dark Haired Girl, a collection of letters and journals from the period.[citation needed]

On February 20, 1974, while recovering from the effects of sodium pentothal administered for the extraction of an impacted wisdom tooth, Dick received a home delivery of Darvon from a young woman. When he opened the door, he was struck by the dark-haired girl's beauty, and was especially drawn to her golden necklace. He asked her about its curious fish-shaped design. As she was leaving, she replied: "This is a sign used by the early Christians." Dick called the symbol the "vesicle pisces". This name seems to have been based on his conflation of two related symbols, the Christian ichthys symbol (two intersecting arcs delineating a fish in profile), which the woman was wearing, and the vesica piscis.[26]

Dick recounted that as the sun glinted off the gold pendant, the reflection caused the generation of a "pink beam" of light that mesmerized him. He came to believe the beam imparted wisdom and clairvoyance, and also believed it to be intelligent. On one occasion, he was startled by a separate recurrence of the pink beam, which imparted the information that his infant son was ill. The Dicks rushed the child to the hospital, where the illness was confirmed by professional diagnosis.[27][verification needed]

After the woman's departure, Dick began experiencing strange hallucinations. Although initially attributing them to side effects from medication, he considered this explanation implausible after weeks of continued hallucination. He told Charles Platt:

"I experienced an invasion of my mind by a transcendentally rational mind, as if I had been insane all my life and suddenly I had become sane."[28]

Throughout February and March 1974, Dick experienced a series of hallucinations which he referred to as "2-3-74",[21] shorthand for February–March 1974. Aside from the "pink beam", he described the initial hallucinations as geometric patterns, and, occasionally, brief pictures of Jesus and ancient Rome. As the hallucinations increased in duration and frequency, Dick claimed he began to live two parallel lives—one as himself, "Philip K. Dick", and one as "Thomas",[29] a Christian persecuted by Romans in the first century AD. He referred to the "transcendentally rational mind" as "Zebra", "God" and "VALIS" (an acronym for Vast Active Living Intelligence System). He wrote about the experiences, first in the semi-autobiographical novel Radio Free Albemuth, then in VALIS, The Divine Invasion, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer and the unfinished The Owl in Daylight (the VALIS trilogy).[citation needed]

In 1974, Dick wrote a letter to the FBI, accusing various people, including University of California, San Diego professor Fredric Jameson, of being foreign agents of Warsaw Pact powers.[30] He also wrote that Stanisław Lem was probably a false name used by a composite committee operating on orders of the Communist party to gain control over public opinion.[31]

At one point, Dick felt he had been taken over by the spirit of the prophet Elijah. He believed that an episode in his novel Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said was a detailed retelling of a biblical story from the Book of Acts, which he had never read.[32] He documented and discussed his experiences and faith in a private journal he called his "exegesis", portions of which were later published as The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick. The last novel he wrote was The Transmigration of Timothy Archer; it was published shortly after his death in 1982.[citation needed]

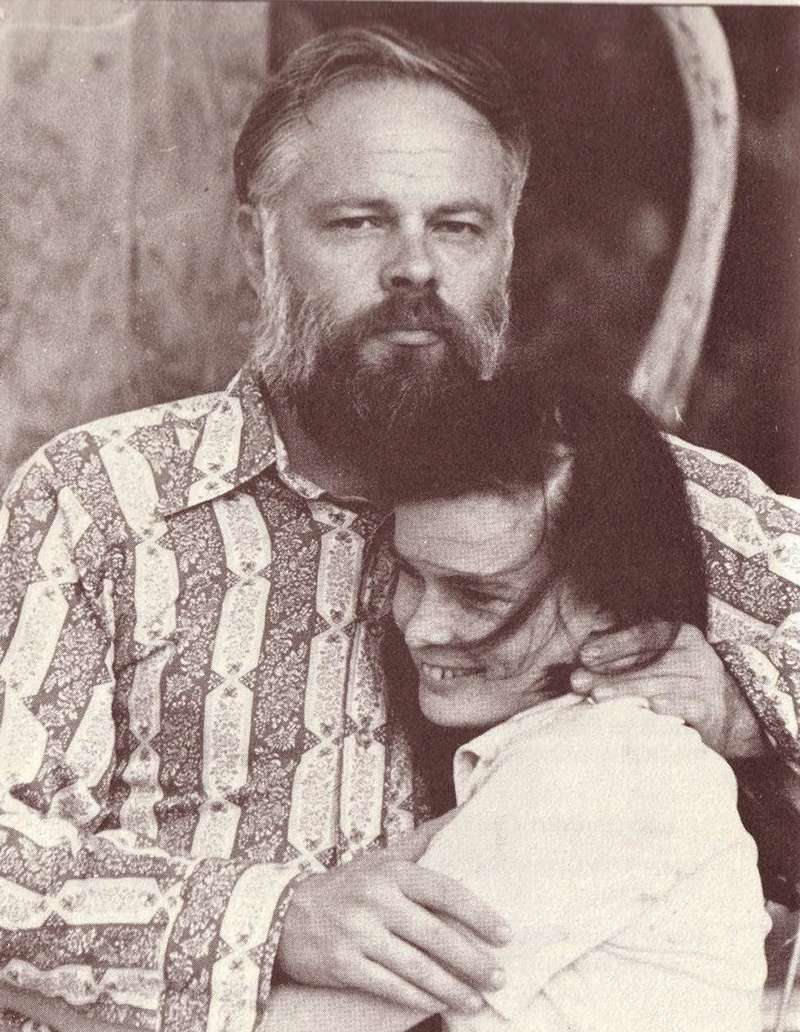

Dick had three children, Laura Archer Dick[33] (born February 25, 1960 to Dick and his third wife, Anne Williams Rubenstein), Isolde Freya Dick[34] (now Isa Dick Hackett) (born March 15, 1967, to Dick and his fourth wife, Nancy Hackett), and Christopher Kenneth Dick (born July 25, 1973, to Dick and his fifth wife, Leslie "Tessa" Busby).[citation needed]

In 1955, Dick and his second wife, Kleo Apostolides, received a visit from the FBI, which they believed to be the result of Kleo's socialist views and left-wing activities. The couple briefly befriended one of the FBI agents.[35]

He was physically abusive with his third wife, Anne Williams Rubinstein; after one argument in 1963, he attempted to push her off a cliff in a car, then later claimed she was trying to kill him,[36] and convinced a psychiatrist to commit her involuntarily. After filing for divorce in 1964, he moved to Oakland to live with a fan, author and editor Grania Davis. Shortly after, he attempted suicide by driving off the road while she was a passenger.[37]

Dick tried to stay out of the political scene because of high societal turmoil from the Vietnam War. Still, he did show some anti-Vietnam War and anti-governmental sentiments. In 1968, he joined the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest",[17][38] an anti-war pledge to pay no U.S. federal income tax, which resulted in the confiscation of his car by the IRS.[citation needed]

On February 17, 1982, after completing an interview, Dick contacted his therapist, complaining of failing eyesight, and was advised to go to a hospital immediately, but did not. The following day, he was found unconscious on the floor of his Santa Ana, California home, having suffered a stroke. On February 25, 1982, Dick suffered another stroke in the hospital, which led to brain death. Five days later, on March 2, 1982, he was disconnected from life support. After his death, Dick's father, Joseph, took his son's ashes to Riverside Cemetery in Fort Morgan, Colorado, (section K, block 1, lot 56), where they were buried next to his twin sister Jane, who died in infancy. Her tombstone had been inscribed with both of their names at the time of her death, 53 years earlier.[39][40] He died four months before the release of Blade Runner, the film based on his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?.[41]

Dick's stories typically focus on the fragile nature of what is real and the construction of personal identity. His stories often become surreal fantasies, as the main characters slowly discover that their everyday world is actually an illusion assembled by powerful external entities, such as the suspended animation in Ubik,[42] vast political conspiracies or the vicissitudes of an unreliable narrator. "All of his work starts with the basic assumption that there cannot be one, single, objective reality", writes science fiction author Charles Platt. "Everything is a matter of perception. The ground is liable to shift under your feet. A protagonist may find himself living out another person's dream, or he may enter a drug-induced state that actually makes better sense than the real world, or he may cross into a different universe completely."[28]

Alternate universes and simulacra are common plot devices, with fictional worlds inhabited by common, working people, rather than galactic elites. "There are no heroes in Dick's books", Ursula K. Le Guin wrote, "but there are heroics. One is reminded of Dickens: what counts is the honesty, constancy, kindness and patience of ordinary people."[42] Dick made no secret that much of his thinking and work was heavily influenced by the writings of Carl Jung.[39][43] The Jungian constructs and models that most concerned Dick seem to be the archetypes of the collective unconscious, group projection/hallucination, synchronicities, and personality theory.[39] Many of Dick's protagonists overtly analyze reality and their perceptions in Jungian terms (see Lies, Inc.).[citation needed]

Dick identified one major theme of his work as the question, "What constitutes the authentic human being?"[44] In works such as Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, beings can appear totally human in every respect while lacking soul or compassion, while completely alien beings such as Glimmung in Galactic Pot-Healer may be more humane and complex than their human peers.[citation needed]

Dick's third major theme is his fascination with war and his fear and hatred of it. One hardly sees critical mention of it, yet it is as integral to his body of work as oxygen is to water.[45]

Mental illness was a constant interest of Dick's, and themes of mental illness permeate his work. The character Jack Bohlen in the 1964 novel Martian Time-Slip i

Novi Seks Bdsm

Bdsm Strapon Chita

Big Dick Trap Hentai

Sucking Dick Webcam

Degraded Slut Bdsm

Philip K. Dick - Wikipedia

Philip K. Dick - IMDb

Philip K. Dick bibliography - Wikipedia

Электрические сны Филипа К. Дика: смотреть онлайн все ...

10 Best Philip K. Dick Books (2021) - That You Must Read!

Electric Dreams (2017 TV series) - Wikipedia

The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick - Wikipedia

Valis (novel) - Wikipedia

Philip K Dick S