Pelvic Organ Prolapse

🛑 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Reviewed by Traci C. Johnson, MD on January 14, 2021

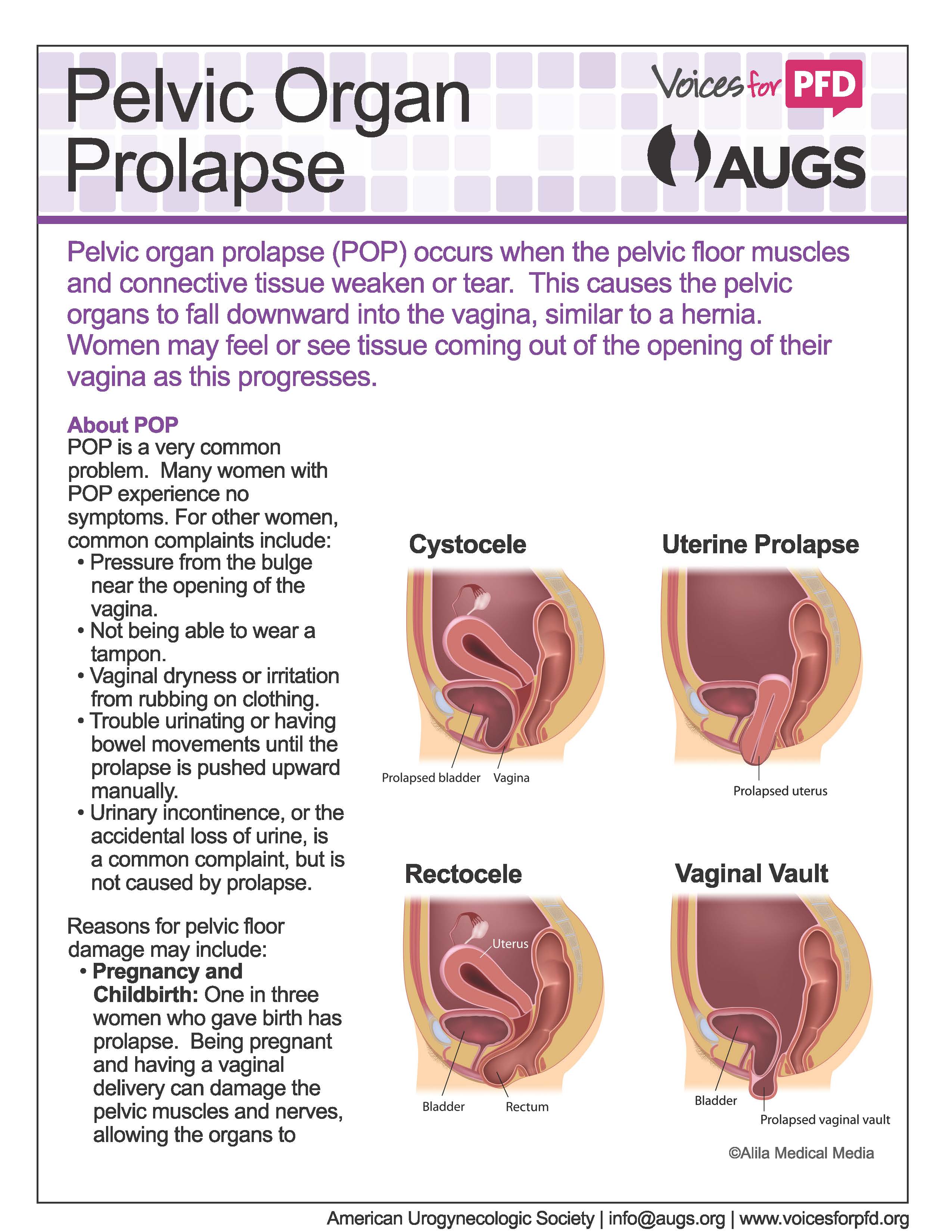

Pelvic organ prolapse, a type of pelvic floor disorder, can affect many women. In fact, about one-third of all women are affected by prolapse or similar conditions over their lifetime.

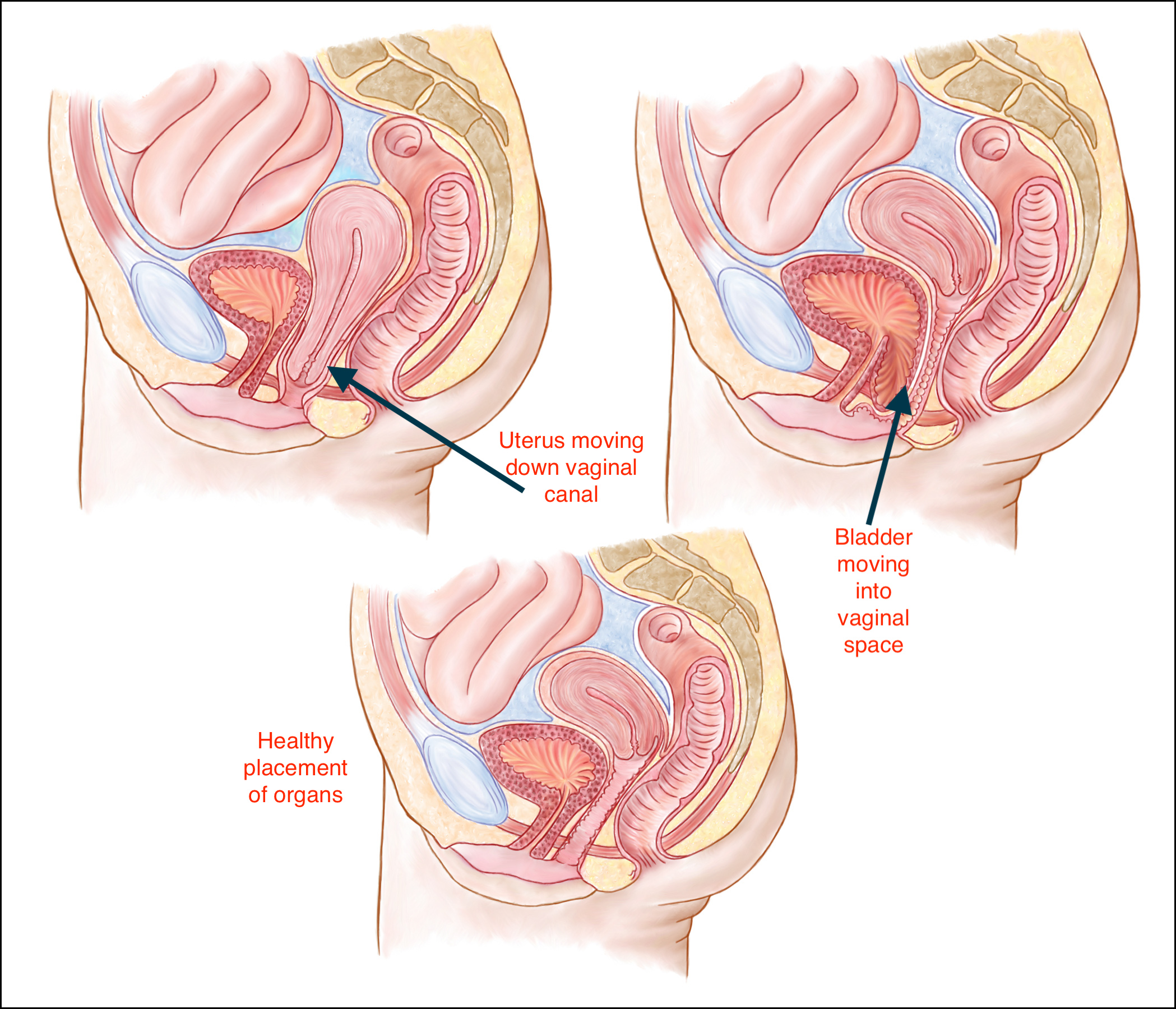

The "pelvic floor" is a group of muscles that form a kind of hammock across your pelvic opening. Normally, these muscles and the tissues surrounding them keep the pelvic organs in place. These organs include your bladder , uterus, vagina , small bowel, and rectum.

Sometimes, these muscles and tissue develop problems. Some women develop pelvic floor disorders following childbirth . And as women age, pelvic organ prolapse and other pelvic floor disorders become more common.

When pelvic floor disorders develop, one or more of the pelvic organs may stop working properly. Conditions associated with pelvic floor disorders include:

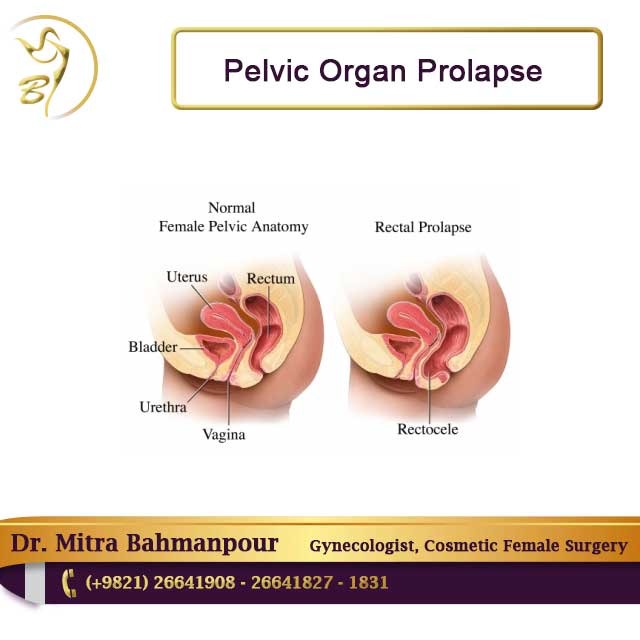

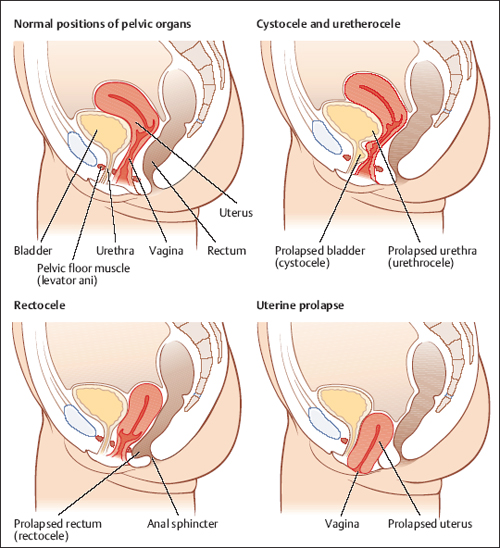

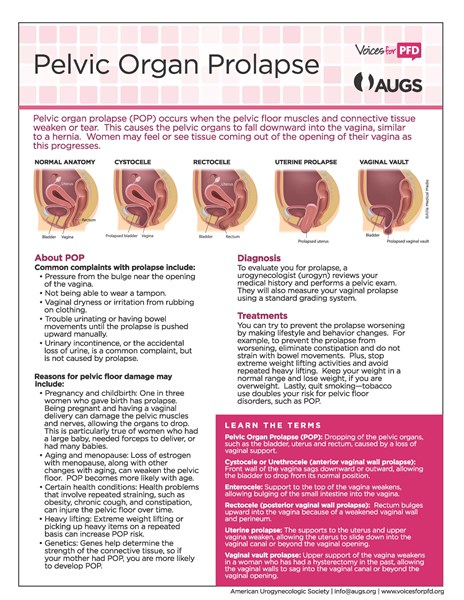

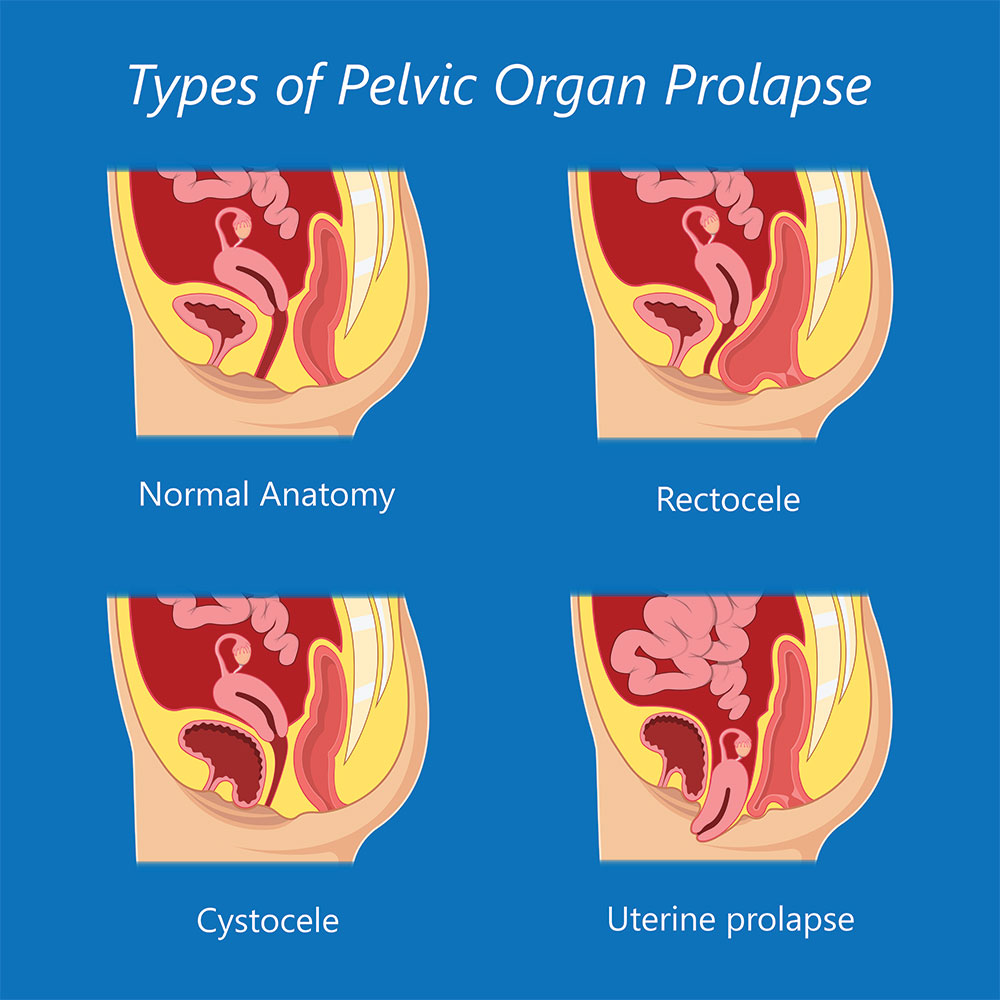

"Prolapse" refers to a descending or drooping of organs. Pelvic organ prolapse refers to the prolapse or drooping of any of the pelvic floor organs, including:

These organs are said to prolapse if they descend into or outside of the vaginal canal or anus . You may hear them referred to in these ways:

Anything that puts increased pressure in the abdomen can lead to pelvic organ prolapse. Common causes include:

Genetics may also play a role in pelvic organ prolapse. Connective tissues may be weaker in some women, perhaps placing them more at risk.

Some women notice nothing at all, but others report these symptoms with pelvic organ prolapse:

Symptoms depend somewhat on which organ is drooping. If the bladder prolapses, urine leakage may occur. If it's the rectum, constipation and uncomfortable intercourse often occur. A backache as well as uncomfortable intercourse often accompanies small intestine prolapse. Uterine prolapse is also accompanied by backache and uncomfortable intercourse.

Your doctor may discover pelvic organ prolapse during a routine pelvic exam, such as the one you get when you go for your Pap smear . Your doctor may order a variety of tests:

Treatment of pelvic organ prolapse depends on how severe the symptoms are. Treatment can include a variety of therapies, including:

Many risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse are out of your control. These include:

But you can reduce the likelihood you will have problems. Try these steps:

SOURCES: WebMD Health Guide: "Pelvic Organ Prolapse." Magee-Womens Research Institute Center for Research in Women's Bladder & Pelvic Health, Pittsburgh, Pa: "Pelvic Organ Prolapse." National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Child Health & Human Development: "Research on Gynecological Disorders." National Association for Continence: "Pelvic Organ Prolapse."

© 2005 - 2021 WebMD LLC. All rights reserved.

WebMD does not provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System - Wikipedia

Pelvic Organ Prolapse : Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment

Pelvic Organ Prolapse - Cancer Therapy Advisor

Pelvic Organ Prolapse , Animation - YouTube

Pelvic Organ Prolapse - Physiopedia

Headlines

Regimens

Drugs

Conferences

Clinical Resources

Tools

Multimedia

CME

Jobs

Cancer Therapy Advisor Weekly Highlights

Cancer Therapy Advisor Daily Update

I would like to receive relevant information via email from Cancer Therapy Advisor / Haymarket Medical Network.

By registering you consent to the collection and use of your information to provide the products and services you have requested from us and as described in our privacy policy and terms and conditions

Next post in Obstetrics and Gynecology

Close

Some areas of this page may shift around if you resize the browser window. Be sure to check heading and document order.

Close more info about Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Close more info about Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Close more info about Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Close more info about Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Close more info about Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Other symptoms associated with prolapse include:

tenesmus (sense of incomplete evacuation)

Pelvic or vaginal pain is another symptom that has been studied in relationship to pelvic organ prolapse and again there is no relationship except an inverse one in that with worsening prolapse any discomfort improves.

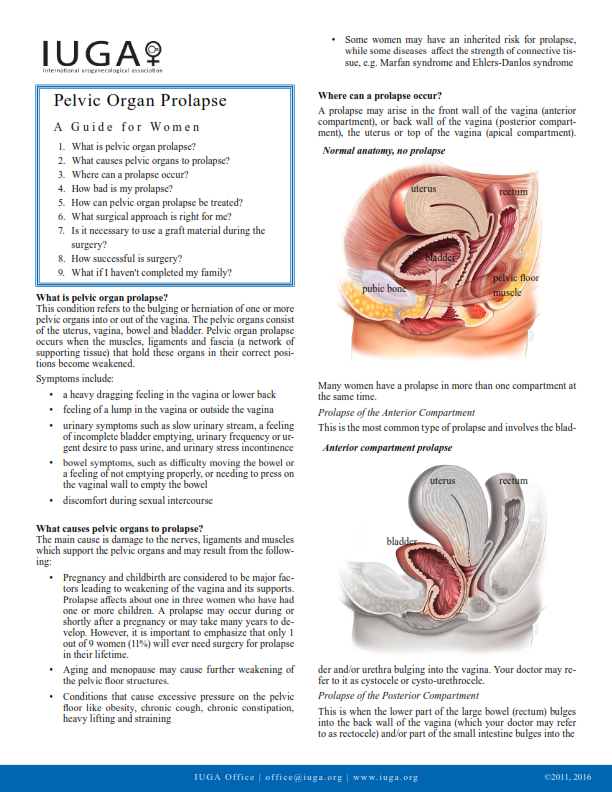

The incidence of pelvic organ prolapse in the population is difficult to estimate as there is no good standard definition. If we use the definition of a vaginal bulge that protrudes beyond the hymen in a symptomatic patient then roughly 3-5% of women will have pelvic organ prolapse.Women have about an 11% incidence of undergoing surgical correction of prolapse at some point in their lives and it is the most common indication for hysterectomy in menopausal females.

Well established risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse include:

women who have had one or more term pregnancies

women who have had prior pelvic organ prolapse surgery

The amount that each of these risk factors contributes is not known but they are consistently identified in most epidemiologic studies.

There are several studies looking at family history of pelvic organ prolapse and there appears to be a weak relationship. There are several ongoing genetic link studies but the findings, while interesting, are still very preliminary. There are only a few studies looking at how physical activity, as related to job or profession, affects pelvic organ support. From limited data there is some evidence to suggest that manual labor and lifting at work play a role.

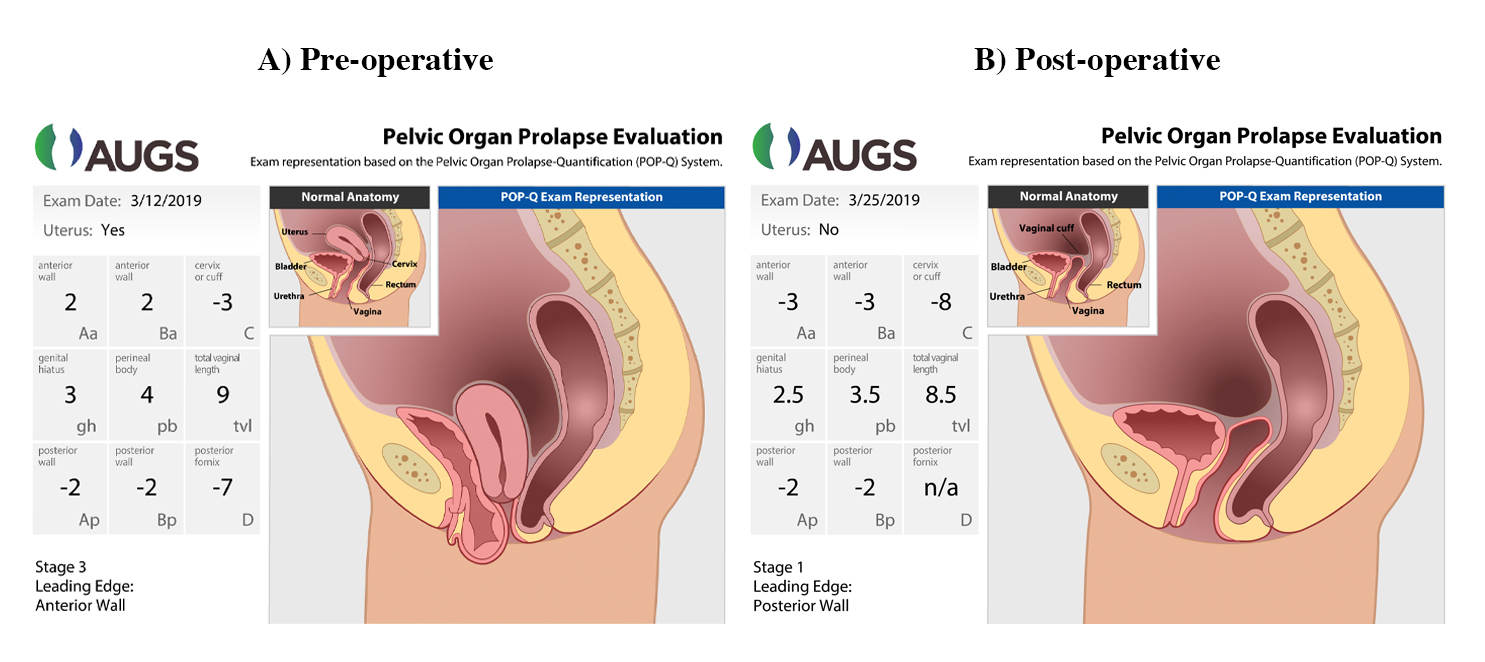

Diagnosing pelvic organ prolapse should be very easy and straightforward; however, there are a few things to keep in mind. First and foremost, the disease has not been rigorously defined. The current trend in the literature is any vaginal wall or cervix extending beyond the hymenal remnants is considered prolapse. The NIH has defined pelvic organ prolapse as POPQ stage II or greater-the leading edge can be above the hymenal remnant (see the POPQ exam below).

The degree of vaginal support has only recently been described for general populations of women. Four studies have all demonstrated that up to 40%percent of normal asymptomatic women will exams where the leading vaginal edge is just above the hymenal remnants making the NIH definition too inclusive. Therefore, In common practice the definition of pelvic organ prolapse is any patient with complaints of a vaginal bulge that can be seen or felt by the patient.

On physical exam a vaginal wall bulge or cervix should be demonstrated protruding to or beyond the hymenal remnants. The findings should be confirmed by the patient with either visualization (with the assistance of a hand held mirror) or by the patient directly palpating the bulge during the exam.

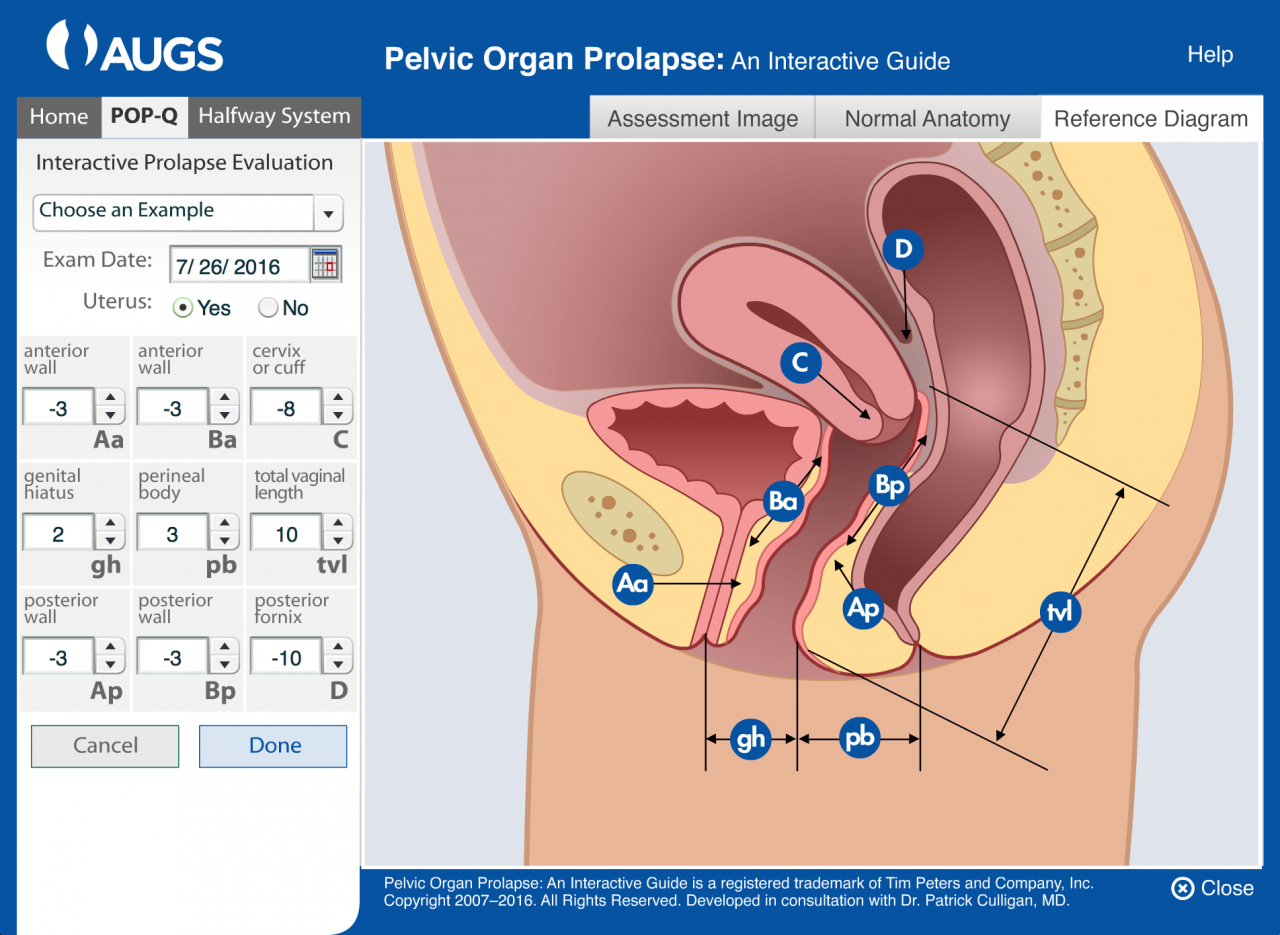

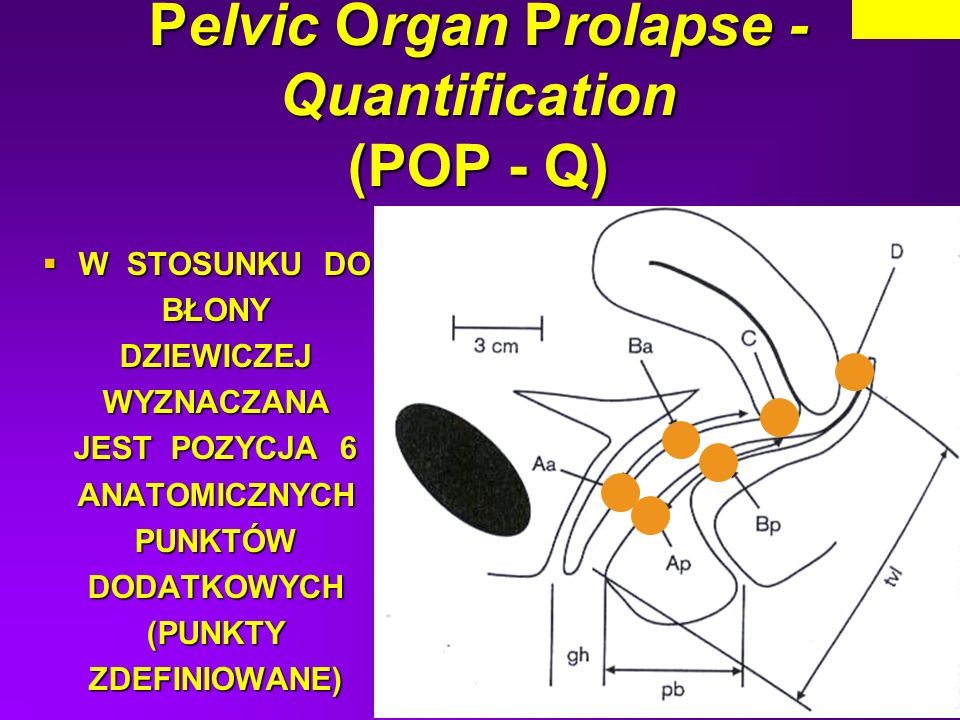

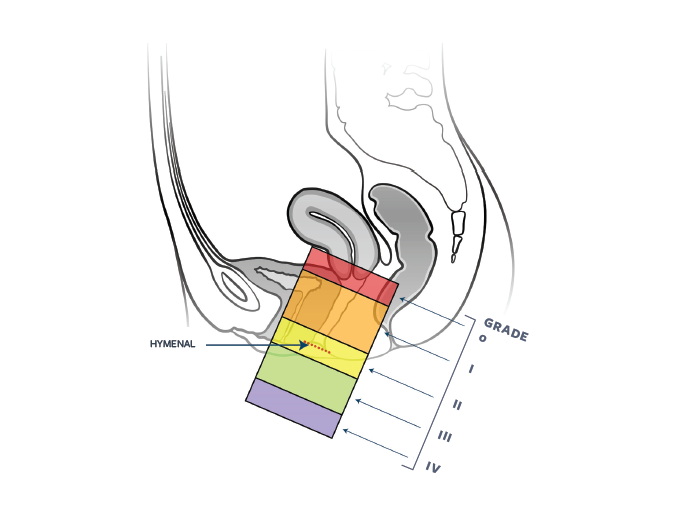

Pelvic organ prolapse should be described using the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POPQ). A full understanding of the nine measured points and how to obtain them is described under knowledge. An understanding of the ordinal staging system will be described here and is frequently substituted for the full POPQ description. It has been described as the simplified POPQ.

To describe vaginal support using the simplified POPQ you divide the vagina into 3 areas or walls; Anterior, Apical and Posterior (if the patient has a cervix that is described as a fourth area). To describe the anterior and posterior walls a point or ruggal fold is identified about 3 cm’s proximal to the hymenal remnants on the wall being examined. The patient is asked to cough or Valsalva and where that identified point descends to in relation to the hymenal remnants is noted. Typically the exam is done with a disarticulated Graves speculum (using the posterior blade) or Simms speculum to retract the posterior wall while examining the anterior wall and vice versa.

Stage 1: If the point or rugal fold remains greater than 1 cm (roughly a fingerbreadth) above the hymenal remnants then that segment is described as stage 1.

Stage 2: If the point or rugal fold descends to within an area described as one centimeter above the hymenal remnants to one centimeter past the hymenal remnants it is described as stage 2.

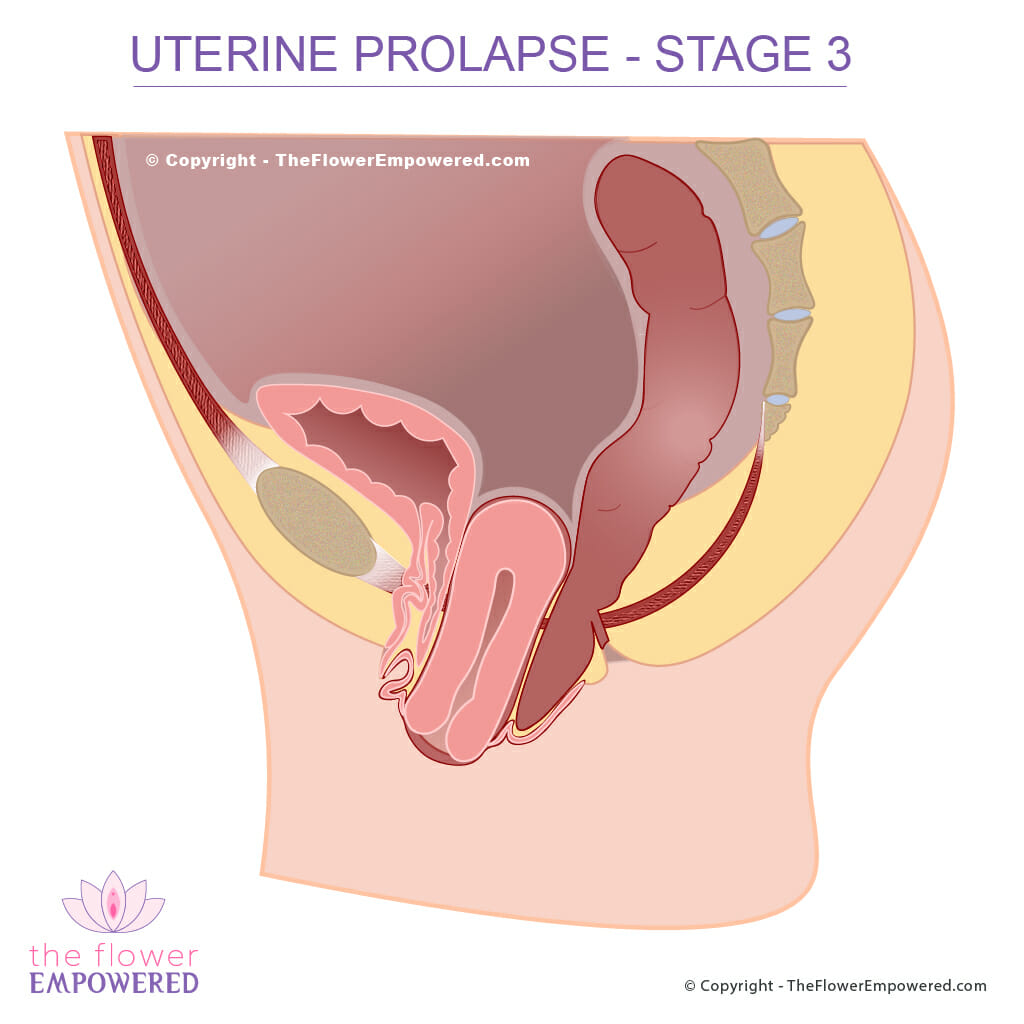

Stage 3: If the point descends greater the one centimeter beyond or past the hymenal remnants but is not complete vaginal eversion then it is described as stage 3.

Stage 4: If there is complete eversion of the wall in question outside the hymenal remnants it is stage IV.

The key to remembering the system is stage 2. If the point on the vaginal wall (or cervix) being evaluated descends to the hymenal remnants or just above or below (1 cm or one fingerbreadth above or past), it is stage 2. If the point being evaluated remains well above the hymenal remnants (greater than 1 cm, or 1 fingerbreadth), it is stage 1. If it descends well past the hymenal remnants (greater than 1 cm, or 1 fingerbreadth), it is stage 3. Complete uterine procidentia or vault eversion is stage 4.

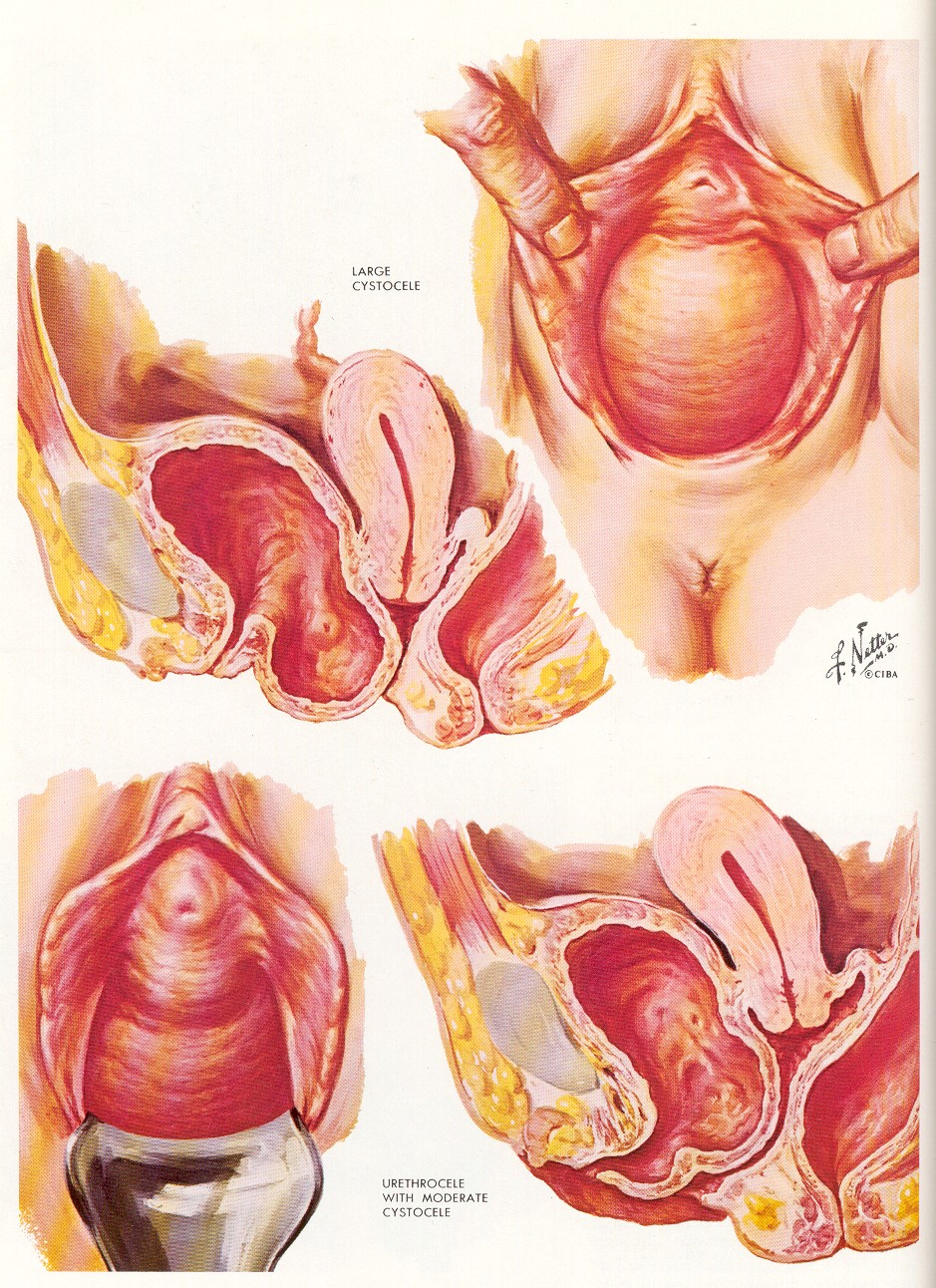

A second commonly used technique to describe pelvic organ prolapse is the Baden and Walker “halfway” system. The Baden and Walker system describes six points: urethrocele, cystocele, uterine prolapse, culdocele, and rectocele.

Stage 0: Normal position for each respective point

Stage 1: The point in question descends halfway to the hymen during cough or strain.

Stage 2: The point in question descends to the hymen during cough or strain.

Stage 3: The point in question extends halfway past the hymen during cough or strain.

Stage 4: The point in question extends maximally.

It is important to remember that if no vaginal or cervical protrusion can be identified on physical exam in the dorsal lithotomy position then the patient should be re-examined standing. If in both positions no vaginal bulge can be identified then the patient probably doesn’t have pelvic organ prolapse and another source should be sought to explain her complaints.

Imaging modalities to describe pelvic organ prolapse are currently not clinically indicated for evaluation of prolapse. The following are all imaging modalities that are being studied, but their clinical utility has not yet been demonstrated. Therefore, their routine use in diagnosing pelvic organ prolapse is not indicated.

These radiographic studies can help in better understanding functional abberations (the associated symptoms of urinary incontinence or obstruction, fecal incontinence or constipation) but should not constitute part of a routine evaluation of patients with pelvic organ prolapse.

Vaginal bulges or protruberances that are suspicious for being a vaginal wall cyst or urethral diverticula can be assess by radiographic studies, but again should be reserved for instances where the diagnosis is in doubt. Pelvic MRI can differentiate cystic vaginal wall structures and urethral diverticulum from prolapse. Pelvic Ultrasound is another modality that can help but doesn’t give as much information as MRI.

Other diseases that can mimic the pelvic organ prolapse symptoms of pressure or “a sense of something falling out” are urogenital atrophy and severe irritation of the vaginal mucosa from a Candida or bacterial source, and a large urethral diverticulum or vaginal wall cyst can present as a bulge that the patient can see or feel. Outside of these few conditions there are not many diseases that can be mistaken for pelvic organ prolapse.

Defining pelvic organ prolapse using currently published guidelines suggest using POPQ stage II, III or IV as anatomically defining pelvic organ prolapse. The description of POPQ stage II includes subjects where the leading edge is one centimeter above to one centimeter past the introitus. This definition was developed at an NIH consensus conference in the absence of knowledge regarding what POPQ stages represented normal support and without any information regarding surgical outcomes and what level of support would result in resolution of symptoms or “cure from prolapse”.

Since that time several large studies of general asymptomatic female populations have demonstrated the up to 40% of normal asymptomatic females have vaginal exams where the leading edge comes to within one centimeter of the introitus and should be considered normal. Also, postoperatively if the vaginal walls remain at or just above the hymenal remnants patients report resolution of symptoms and are pleased with their surgical outcome.

Therefore, the NIH definition is over inclusive and is currently losing favor as a definition for pelvic organ prolapse. However, as of 2011 the NIH is the only formal definition of pelvic organ prolapse in existence. Using the NIH definition of pelvic organ prolapse as POPQ stage II, III, IV exams would suggest that over 40% of women have pelvic organ prolapse. This is the biggest argument against the IH definition as it is too inclusive.

The pelvic organ prolapse quantification system or POPQ defines 9 measures in and around the vaginal tube which are recorded in centimeters. These nine points are recorded in a 3×3 grid and then translated into a 5 stage ordinal staging system; Stage 0, Stage I, Stage II, Stage III, Stage IV. The nine measures described are Gh, Pb, Tvl, Aa, Ba, C, Ap, Bp and D. The measures are all in centimeters using ruler (often a wooden pap smear spatula that is marked in pen with centimeter gradations). The Gh is the genital haitus measured from the urethral meatus to the posterior fourchette during cough or Valsalva.

The Pb is the perineal body measured forms the posterior fourchette to the rectum during cough or Valsalva. The Tvl is the total vaginal length measured with all prolapse reduced and at rest form the hymenal remnants to the apex of the vaginal vault. This represents the potential vaginal length and is the only point measured at rest.

The Aa and Ba are two on the anterior vaginal wall and represent point A anterior and point B anterior and both are measured during cough or Valsalva. Point Aa is fixed and defined as a midline point 3 centimeters proximal to the hymenal remnants and usually the urethral meatus. Point Ba is more difficult to conceptualize and is the most dependent point between point Aa and the cervix or cuff.

Point C is the cervix or cuff scar in a hysterectomized patient and is measured during cough or Valsalva. The Apand Bpare two on the posterior vaginal wall and represent point A posterior and point B posterior and both are measured during cough or Valsalva. Point Ap is fixed and defined as a midline point 3 centimeters proximal to the hymenal remnants. Point Bp is more difficult to conceptualize and is the most dependent point between point Ap and the cervix or cuff. Point D is the posterior fornix in a subject with a uterus and is measured during cough or Valsalva. In a patient who has had a complete hysterectomy there is no point D recorded.

For points Aa, Ba, C, Ap, Bp and D the values are measured in relation to the hymenal remnants during a cough or Valsalva. They can be negative or positive values with the hymenal remnants being 0. If the point being measured remains above the hymenal remnants then it is recorded as the numbers of centimeters above the hymenal remnants and recorded as a negative number. If the point descends to the hymenal remnants then it is recorded as 0. If the point being measured descends beyond the hymenal remnants then it is recorded as the numbers of centimeters beyond the hymenal remnants and recorded as a positive number.

The greatest value among points Aa, Ba, C, D, Ap, Bp is used to give an ordinal stage. For the POPQ only 1 overall stage is given.

Stage 0: Points Aa, Ba, Ap and Bp are all -3 cms and points C and D are no greater then (-) TVL -2. For example if the Tvl is 10 cms then Points Aa, Ba, Ap, Bp must be -3 cms and points C and D must be no greater then -8cms.

Stage I: The greatest value among points Aa, Ba, Ap, Bp, C and D must all be less the -1 cms.

Stage II: The greatest value among points Aa, Ba, Ap, Bp, C and D must be between -1 cm and +1 cm.

Stage III: The greatest value among points Aa, Ba, Ap, Bp, C and D must be greater than +1cms but less than TVL -2cms.

Stage IV: The greatest value among points Aa, Ba, Ap, Bp, C and D must be greater than Tvl -2cms.

For points Gh, Tvl and Pb the values are recorded in centimeters and can only have positive designations. They are not used in determining the stage.

There are three options to treat pelvic organ prolapse and patients should be counseled on all three options:

There is very little data about the natural history of pelvic organ prolapse but it has always just been accepted (right or wrong) that it is a progressive disease. From the few studies available this does not appear to be the case. While some prolapse may progress (only 5-20%) to more severe stages this is not a universal occurrence and in a few cases there can be some regression. In the majority of patients pelvic organ prolapse is a fairly static disease with little or no progression over 2- 5 years.

In the majority of patients presenting with milder stages of prolapse (POPQ Stage II or early III) there appears from limited data to be little change in their severity over time and therefore observation, or non-intervention, becomes a viable option. If patients are being observed they should be educated about the symptoms of prolapse and follow up visits with re-examination should be planned every 6 months to one year.

The one caveat to simple observation involves subjects with greater degrees of anterior vaginal wall prolapse, patients where the anterior vaginal wall is a more severe POPQ stage III and IV (the anterior vaginal wall 5-10 cms beyond the hymenal remnants). In these subjects an assessment of renal function is warranted as ureteral obstruction and renal injury has been described. Annual serum creatinine to assess renal function and renal ultrasound looking for hydronephrosis is probably sufficient. If renal insult is identified then therapy is mandatory.

Once patients decide on therapy the interventions to relieve symptoms there are two; pessary management or surgical correction.

Pessary management historically has been relegated to patients who were not surgical candidates or as a bridge therapy to provide symptom relief while patients awaited surgical intervention. However, as surgical success rates have been called into question pessary management has become a more viable long term option for many patients. About 60% of subjects initially fitted with a pessary will chose to continue use beyond 4-6 months.

There are over 20 different pessaries of various shapes and sizes to treat pelvic organ prolapse. The majority of prolapse can be managed by one of three pessaries: the ring with support (or some variant), the Gelhorn, and the Cube. The ring and cube pessaries can treat any type of prolapse while the Gelhorn is suggested for anterior wall prolapse.

If observation and pessary management are not acceptable options, then surgery is the only other choice. Surgical correction depends on the defect and deciding on which procedure to perform depends on which anatomic compartment is involved and whether or not to use any material to re-inforce the repair.

The vagina is classically divided into three compartments; Anterior, Apical and posterior and there are different surgical therapies that depend on which compartment is being addresses.

For Anterior vaginal wall defects or cystoceles a standard anterior repair/colporraphy (placating the endopelvic fascia in the midline) is a good choice.The literature on unacceptably high failure rates with standard anterior colporraphy are a misconception based solely on anatomic definitions of success.When the studies are evaluated based on patients level of symptom relief or overall satisfaction the success rates for anterior colporraphy are in the 90% range.

Mesh re-enforced anterior coplorraphy

The universal use of a mesh to re-enforce an anterior colporraphy is currently being debated and studies. It is not to be recommended unless the surgeon is well versed in the literature and can adequately counsel patients and manage complications.The use of synthetic mesh in anterior vaginal prolapse repairs is currently being studied to determine in which patients the benefits outweigh the risks. Once these studies are complete better guidelines for when to use synthetic meshes will emerge.

The use of biologic meshes to re-enforce anterior colporraphies may have some merit as they appear to slightly increase efficacy and don’t carry the complications that are associated with synthetic meshes.The decision on whether or not to use a synthetic or biologic mesh in all primary repairsshould be thoroughly discussed with patients as it may only improve success rates by a few percent but can carry other consequences.

For posterior vaginal wall prolapse or rectocele repair there are three basic repair techniques: Levator plication or endopelvic fascia plication, site specific repairs, or standard repair reinforced with mesh.

The classic levator/endopelvic fasciaplication is the repair of choice for most surgeons.The biggest concern with this procedure is an over correction, leading to vaginal stenosis or a posterior “shelf” being created.This can lead to dyspareunia in up to 30% of patients undergoing this type of repair.On way to avoid this is to perform a “looser” repair and check the vaginal canal after each suture is placed to avoid over correction.

A site specific repair is done when a specific defect in the posterior vaginal wall endopelvic fascia is identified during dissection.The edges of the defect are re-approximated with interrupted sutures in the fashion of any classic hernia repair.he site specific has been studied in comparison to the classic posterior/endopelvic fascia plication and it does not have an obvious advantage in either recurrence or dyspareunia.

Either an elevator/endopelvic fascia plication or a site specific repair has a high degree of efficacy with a low recurrence rate in the 5% range. Despite this high level of efficacy investigators have studied the addition of mesh (either biologic or synthetic) to these repairs to further strengthen them.

The literature here is sparse and as yet no clear benefit can be seen to adding mesh (either synthetic or biologic) to these repairs. Eventually, as with the anterior repair, we will identify a sub-set of patients who require mesh augmentation of a posterior repair. Currently, its routine use cannot be advocated.

The apical segment or cervix is more difficult to assess and the decision as to who needs surgical correction is controversial. If the cervix descends to within 3 cms of the hymen or lower it is appropriate to offer a hysterectomy with your other prolapse procedures. If the vaginal apex (Posterior fornix or vaginal cuff) descends to within 3-4 cms of the hymenal remnants then an apical procedure should be performed as well.

There are two areas of controversy in the management of apical support defects. First is the old notion of always performing a hysterectomy (regardless of how well the uteruus is supported) with all prolapse procedures is obselete. The literature looking at prophylactic hysterectomy as an adjunct to prolapse surgery demonstrates either no benefit or worse outcomes in patients undergoing a concomitant hysterectomy. The second is the new thinking on anterior vaginal wall prolapse is that this is just a reflection of an apical defect and if the apex can be drawn back up to its normal position then most anterior wall defects will be automatically corrected. Proponents of this theory feel that most cystoceles requiring apical support procedures and not anterior wall procedures. This concept is still in its infancy and has not been rigorously tested in clinical trials.

The current gold standard for vaginal vault prolapse is the abdominosacrocoplpopexy. It is a procedure where the vaginal apex is suspended from the sacrum by an interposed piece of synthetic mesh. The success rate of this procedure is approximately 90%, if success is defined as resolution of symptoms. This is one area where synthetic mesh has demonstrated superiority to biologic or absorbable meshes.

The procedure can be performed as an open procedure, a laparoscopic procedure or a robotic procedure. The advantages/disadvantages to each technique are the advantages/disadvantages for any open vs. laparoscopic vs. robotic procedure. The technique should be left up to the surgeon and patient as to which technique they are most comfortable with.

One area of controversy involves the addition of a hysterectomy to the abdominosacrocolpopexy. There are several studies demonstrating apical erosion rates of up to 20-30% in patients who undergoes a hysterectomy concurrent with an abdominosacrocoplopexy. This has lead to the recommendation that the two procedures not be performed concurrently and instead the patient should undergo a staged procedure with the hysterectomy first followed by the abdominosacrocoplopexy after healing is complete. This is not a universal recommendation and one report revealed no increase in apical mesh exposure with the addition of a hysterectomy as compared to vaginal vault suspension.

Transvaginal vaginal vault suspension procedures

There are various vaginal procedures to correct apical prolapse that have gained popularity particularly if used in conjunction with a hysterectomy. These repairs include:

sacrospinous vaginal vault fixation

They are all performed using suture to attach the vaginal cuff to the various ligaments or muscular fascia noted. Efficacy is high and complications are low. They all have success rates that are in the 85-90% range for relief of symptoms. Complications vary for each procedure but in general pelvic and buttock pain are common after the sacrospinous vaginal vault fixation and illeococcygeous suspension, and ureteral injury is a potential complication of the uterosacral ligament suspension.

As with an abdominosacrocolpoexy the choice of procedure should be left up to the surgeon as to which procedure they feel most confident with. In the few trials comparing the vaginal fixation procedures to the Gold Standard Abdominosacrcolpopexy the efficacy is slightly less but the morbidity and cost are also slightly less.

A colpectomy or LeForte’s colpocleisis are obliterative procedures that close off the vaginal canal and preclude any vaginal coitus. They are procedures with few surgical complications and very high patient satisfaction if patients are properly counseled pre-operatively. The colpectomy is performed on subjects who have previously had a hysterectomy and now have vaginal vault prolapse. It is performed by excising the vaginal mucosa in its entirety back to the level of the introitus and the closing the vault with a series of purse string sutures. The vaginal mucosal edges are then closed effectively abolishing the vaginal canal and reapproximating the bladder to the rectum.

A LeForte colpocleisis is performed on subjects who have complete uterine procidentia and the by excising a rectangular segment of both the anterior and posterior vaginal mucosa and the approximating these two denuded areas and obliterating the central vaginal canal. A lateral channel on either side is left open for drainage of cervical secretions.

The addition of either a synthetic mesh or a biologic/xerograph mesh to re-enforce an anterior colporraphy is currently a widely accepted practice but remains controversial in the literature. The misconception of high anatomic failure rates reported in the literature lead to the development of reinforcing meshes for anterior colporraphies. As mentioned above the studies suggesting high failure rates (approaching 70%) had many problems and dramatically over estimated failure rates. The subsequent research on the addition of a mesh is inconsistent and leaves the clinician with mixed signals on how best to proceed.

A simple summary statement comes from a 2010 Cochran library review. It states that incorporating either synthetic or absorbable meshes into Anterior compartment repairs results in better anatomic outcomes but does not improve patients symptoms relief. If pelvic organ prolapse is a disease of symptoms and our goal is to provide symptom relief then the routine addition of mesh to augment repairs appears unjustified.

If a clinician decides to use a synthetic mesh kits to re-enforce an anterior colporraphy they need to be aware that it carries a 10-15% risk of mesh erosion into the vaginal canal. About 2-10% of meshes implanted that will require re-operation to excise. If the clinician uses a xenograft or absorbable mesh the rate of exposure requiring re-operation is <1%. The risk of re-operation for recurrent symptomatic prolapse following a mesh augmented repair is 2-5%.

If a simple anterior colporraphy is performed there is obviously no risk of re-operation for a mesh complication and a 5-10% risk of re-operation for recurrent symptomatic prolapse. Overall, about 5-10% of patients will require re-operation for one reason or another. Therefore the decision to use meshes or not is an individual choice with no current guidelines or recommendations. Current research is being aimed at determining which patients are at very high risk of recurrence after standard anterior colporraphies and possibly restricting mesh use to this population. The population at high risk for recurrence has not yet been identified.

Deciding on which pessary is to place is fairly simple. A ring w/support is always an adequate choice. It is the preferred choice of most Urogynecologists and can manage most types of prolapse.

The decision on which size to fit is based on the size of the vaginal introitus. If the introitus is 2 cms as measured from the urethral meatus to the posterior fourchette then start with a #2 ring pessary w/support. If it is 3 cms try a #3 and so on. If the patient cannot keep or tolerate a ring w/support in place then try a cube. Again, in a patient with a 2 cm introitus try a #2 cube and so on. The gelhorn works best with anterior defects as the stem is placed at the posterior fourcheet and the cup is directed to the anterior vaginal wall.

After the pessary is placed ask the patient to ambulate. If it is comfortable and doesn’t fall out it is fit correctly. Always fit the smallest pessary that doesn’t fall out and restores support. The patient should return in 1-2 weeks to assess their level of satisfaction. If the patient is satisfied, on return teach them how to place and remove the pessary on their own and start them on an estrogen cream every other night.

The estrogen cream will help reduce complications of ulcerations. Patients should remove the pessary once each week at night, clean it , leave it out overnight and replace it the following morning. If the patient cannot remove clean and replace the pessary on their own they can come to the office every 2-4 months to have it removed, cleaned and replaced.

For a general gynecology practice having a modest selection of pessaries will save time and trouble for your patients. It is suggested that having two of each of the following pessaries is sufficient to manage most patients: #2-#6 ring w/support, and #1-#5 cube. Pessaries often come with an antibiotic cream as part of the “kit”. Generally, these antibiotic creams are not necessary but can help patients with excessive discharge who are being managed with every other month cleanings. In subjects that can remove and clean the pessary weekly no supplemental antibiotic creams are necessary.

If vaginal ulcerations arise with pessary use the best course of action is to remove the pessary and leave it out until the ulcers resolve. Estrogen cream and antibiotic cream do not treat ulcers if the pessary is left in place.

For observation there are few complications except a 5-20% chance of worsening prolapse. If the prolapse being observed extends beyond the protection of the vagina and labia the vaginal walls can become ulcerated with secondary infection (usually a mild local infection). A rare complication of observation is hydronephrosis and renal damage. This only occurs with advance degrees of anterior vaginal wall prolapse (large POPQ stage III and POPQ stage IV).

Complications of pessary management involve vaginal discharge and ulcerations of the vaginal epithelium with vaginal bleeding. The discharge is not always infectious and can be managed with topical estrogen cream alternating with topical antibiotic cream and more frequent removal and cleaning (weekly removal and cleaning is ideal). If vaginal ulcerations occur removing the pessary for 3-6 weeks and allowing the ulcer to heal will work in the majority of patients. Occasionally ulcers will heal with the use of estrogen cream alternating with an antibiotic cream and leaving the pessary in place.

The complications of any surgery include: bleeding, infection and damage to pelvic organs. These are all rare complications. Complications unique to specific procedures include ureteral injury or compromise, which occurs in up to 11% of subjects undergoing an uterosacral ligament suspension and ureteral patency should always be established after these sutures are tied down. Also, if placing a synthetic mesh in the anterior compartment a 1-10% risk of bladder perforation is present. This occurs more commonly if the deep sub endopelvic fascia technique is being used.

For apical and anterior vaginal segment repairs there is a risk of developing urinary issues post-operatively. Generally about 10% will develop symptomatic incontinence that will require some form of additional treatment (some surgical and some medical/behavioral). Please see the section on mesh placement for other complications of synthetic mesh placement

Dyspareunia occurs in 10-15% of subjects undergoing a levatorplasty as part of a posterior repair. This occurs when the apical or proximal sutures are placed too laterally and when tied down form a posterior vaginal band. After every posterior levatorplsasty suture is placed two fingers should be placed into the vaginal canal to insure that no band is being formed.

All pelvic organ prolapse operation there is about a 5-10% risk of failure and the prolapse recurring. Rates of recurrence are slightly lower for posterior repairs and slightly higher for anterior or apical vaginal repairs.

For observation of minimally symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, roughly 70-80% will have minimal change in their exam findings and symptoms over time. About 20-25% of subjects will see a worsening of their disease and ultimately elect an intervention. Rarely (2-5%) does the prolapse improve. About 80% of patients that elect pessary use will be successfully fitted for a pessary. Of those successfully fitted only about 50-60% will use the pessary beyond the initial 3 months.Those that select another form of therapy do so because of discomfort, vaginal discharge or from bother with the management issues involved with pessary use.

For those electing reconstructive surgery, about 10% will need further therapy for a recurrence of their prolapse or urinary tract symptoms. Generally, the recurrences will occur in the first two years.

Pelvic organ prolapse is not a life threatening disease, with the rare exception of renal failure with advanced anterior vaginal segment prolapse (large POPQ stage III and POPQ stage IV prolapse). Instead it is a disease of quality of life. Therefore, if a patient selects no therapy it will not adversely affect her physical health but may affect her sense of well being.

Swift, SE, Wioodman, P, O’Byle, A, Kahn, M, Valley, M. “Pelvic organ support study (POST): the distribution, clinical definition and epidemiology of pelvic organ support defects”. Am J Obstet Gynecol. vol. 192. 2005. pp. 795-806. (Early study describing the distribution of pelvic organ support in over 1000 women attending a variety of outpatient gynecology clinics for annual exams. The authors concluded that a large portion of the population (roughly 40% had pelvic organ prolapse as defined by the NIH criteria despite being asymptomatic. First authors to suggest a more concise definition of prolapse to be a bulge protruding to or beyond the hymen as a clinical definition of prolapse.)

Swift, SE, Barber, MD. “Pelvic organ prolapse: defining the disease”. Female Pelvic Med Reconstruct Surg. vol. 16. 2010. pp. 201-3. (Good editorial/opinion piece collating all the studies on defining the condition of pelvic organ prolapse. The epidemiology, surgical and questionnaire literature involved with defining symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and successful surgical outcomes are reviewed. The authors suggest that based on the literature it is now appropriate to define symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse as any vaginal walls protruding to or beyond the hymenal remnants.)

Woodman, PJ, Swift, SE, O’Boyle, A, Valley, MT, Bland, DR. “Prevalence of severe pelvic organ prolapse in relation to job description and socioeconomic status: a multicenter cross-sectional study”. Inter Urogynecol J. vol. 17. 2006. pp. 340-5. (Study of the effect of job description and socioeconomic factors in the epidemiology of pelvic organ prolapse. The study findings suggest that lower socioeconomic status and job description as laborer are associated with more severe pelvic organ prolapse.)

Miedel, A, Ek, M, Tegerstedt, G, Maehle-Schmidt, M, Nyren, O, Hammarstrom, M. “Short-term natural history in women with symptoms indicative of pelvic organ prolapse”. Inter Urogynecol J. vol. 22. 2011. pp. 461-8. (Population based study done over 5 years looking at the rates of progression and regression of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse.)

Cundiff, G, Amundsen, C, Bent, A. “The PESSARI study: Symptom relief and outcomes of a randomized cross over trial of the ring and Gelhorn pessaries”. Am J Obstet Gynecol. vol. 196. 2007. pp. 405-7. (Good study of optimal pessary use and differences between the two most commonly used pessaries. The authors noted that ring and gelhorn pessaries both improve symptoms equally with equivalent continuation rates suggesting no benefit of one type over the other.)

Adams, EJ, Thomson, AJM, Maher, C, Hagen, S. “Mechanical devices for pelvic organ prolapse in women”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . 2004. (Excellent review on the use of pessaries for treating pelvic organ prolapse. Last updated 2009, the authors found no consensus on how to best use pessaries. There is also no evidence that they work better then surgery or that one pessary is superior to another. Randomized controlled trials to establish best use of pessaries are badly needed.)

Nieminen, K, Hiltunen, R, Takala, T, Heiskanen, E, Merikari, M. “Outcomes after anterior vaginal wall repair with mesh: a randomized, controlled trial with 3 year follow-up”. Am J Obstet Gynecol. vol. 203. 2010. pp. 235-7. (Excellent prospective randomized trial of anterior repair using native tissue vs. an anterior repair with synthetic mesh overlay. Improved anatomic outcomes in the patients who had a mesh overlay but identical symptomatic improvements in both groups. Seventeen percent in the no mesh group and eleven percent in the mesh group required re-operation. There was no difference in new onset dyspareunia between the groups.)

Maher, C, Feiner, B, Baessler, K, Glazener, CMA. “Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapses in women”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010. (Excellent review on all aspects of surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse. The authors concluded that abdominosacrocolpopexy with synthetic mesh has the highest success rate for vaginal vault prolapse, but vaginal procedures had similar patient satisfactions and similar re-operation rates for recurrent prolapse as the abdominosacrocolpopexy. The use of mesh overlays or kits for anteruior vaginal wall (cystocele) repairs improves anatomy but does not improve patient satisfaction. Transvaginal posterior vaginal wall (rectocele) repairs performed transvaginally may be better then trans anal repairs.)

Altman, D, Vayrynen, T, Engh, ME, Axelsen, S, , Falconer, C. “Anterior Colporraphy versus Transvaginal Mesh for Pelvic-Organ Prolapse”. N Engl J Med. vol. 364. 2011. pp. 1826-36. (Excellent prospective randomized trial of Anterior Mesh vs. Standard native tissue repair fort anterior vaginal wall (cystocele) defects. The Mesh Kits had greater anatomic success and a 10% improvement in proplapse symptoms over the native tissue repairs, but there were more returns to the operating room to correct post repair stress urinary incontinence and mesh exposures.)

Copyright © 2017, 2013 Decision Support in Medicine, LLC. All rights reserved.

No sponsor or advertiser has participated in, approved or paid for the content provided by Decision Support in Medicine LLC. The Licensed Content is the property of and copyrighted by DSM.

Sign up to get the latest cancer therapy news in your inbox.

Already have an account? Sign in

here

CancerTherapyAdvisor.com is a free online resource that offers oncology healthcare professionals a comprehensive knowledge base of practical oncology information and clinical tools to assist in making the right decisions for their patients.

Our mission is to provide practice-focused clinical and drug information that is reflective of current and emerging principles of care that will help to inform oncology decisions.

Copyright © 2021 Haymarket Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in any form without prior authorization.

Your use of this website constitutes acceptance of Haymarket Media’s Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions .

You’ve read 1 of 5 articles this month.

We want you to take advantage of everything Cancer Therapy Advisor has to offer. To view unlimited content, log in or register for free.

f_auto" width="550" alt="Pelvic Organ Prolapse" title="Pelvic Organ Prolapse">w_1920/v1560143800/gu0t0urovobjh05qzvgo.jpg" width="550" alt="Pelvic Organ Prolapse" title="Pelvic Organ Prolapse">

f_auto" width="550" alt="Pelvic Organ Prolapse" title="Pelvic Organ Prolapse">w_1920/v1560143800/gu0t0urovobjh05qzvgo.jpg" width="550" alt="Pelvic Organ Prolapse" title="Pelvic Organ Prolapse">