Nurses To The Rescue 1997

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

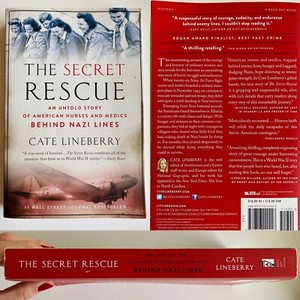

More nurse practitioners are graduating each year than MDs, but will they be prevented from treating patients? (Photo: Jessica Aiduk)

Our latest Freakonomics Radio episode is called “Nurses to the Rescue!” (You can subscribe to the podcast at Apple Podcasts or elsewhere, get the RSS feed, or listen via the media player above.)

They are the most-trusted profession in America (and with good reason). They are critical to patient outcomes (especially in primary care). Could the growing army of nurse practitioners be an answer to the doctor shortage? The data say yes but — big surprise — doctors’ associations say no.

Below is a transcript of the episode, modified for your reading pleasure. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

Let me ask you a quick question. Why do you listen to Freakonomics Radio? I’m guessing it’s for the same reasons that we make it. Because it seems like a good idea to challenge the conventional wisdom once in a while; to dig in and take stuff apart and see how the world really works; also: to explore counterintuitive ideas. Here’s one counterintuitive idea: there’s no way you can give away content like Freakonomics Radio and then expect people to pay for it. Who would voluntarily pay for something you can get free?

But you know what, they do! Not just for Freakonomics Radio, but millions of people do this all the time. Voluntary contributions at museums and other cultural sites; pay-what-you-want meals, and yoga classes. Frankly, this model strikes me as a bit nuts. It makes no sense — and yet, often, it works. And it’s completely Freakonomical. Every week, we give away Freakonomics Radio but we also think it’s worth your support.

The show gets more than 8 million listens every month, so we know a lot of people like it. But, only a very small percentage of listeners make a donation. So, listening — very popular. Giving support to the thing you consume? Not so much.

What’s that about? Maybe the rewards aren’t set up right. But consider this. There’s the short-term reward — a burst of dopamine that makes you feel good right now when you support Freakonomics Radio. Then there’s the long-term reward — keeping something you like healthy and vital for the future — by investing today. Knowing that each week you’re listening to something that you helped make possible. I imagine some of you would be persuaded by that notion. It’s something our friend Richard Thaler, a recent Nobel Laureate, should weigh in on:

Richard THALER: Right, because why should I donate because I can listen for free? So there was a famous paper written by Paul Samuelson defining what’s called the public goods problem in economics and proving that for goods like public radio that anyone can consume without paying that no one will pay for it. And what we know is thankfully some people do contribute. And so the real world is a mixture. There are free riders, and there are cooperators.

So what are you — a free rider or a cooperator? Only you can decide. As for us, here we are, just a podcast standing in front of its audience, asking for money with our transparent, truthful nudge. And we’re going to make it easy.

You can invest in the future of Freakonomics Radio, in future episodes, when you text the word “nudge” to 701-01. You can also go to freakonomics.com/donate and make your donation. Why not, right? After all, you’ve probably been accepting hundreds of nudges for all sorts of things that don’t necessarily make your life better. Twitter notifications on your phone. Those Amazon ads that follow you all the way to your inbox. If you’re working in a big corporate office, your so-called perks — the ping-pong tables and free food — are nudging you to work longer for no extra pay.

Here at Freakonomics Radio, we’re trying to be 100% transparent with our nudges. This show is worth something to you. Otherwise you wouldn’t be listening right now. And we are going to build on the value by making more shows, tell more stories that highlight the amazing connections between economics and human behavior. That’s where your money goes — to making the show. Super simple.

What does that mean? Well, on average, at least five people work on any given episode. Sometimes, it’s as many as eight — Really talented producers who spend their days wrangling the data, lining up the evidence, and tracking down experts that make this show unique. And there are other costs beyond staff — studio time, office space, equipment, engineering and mixing, editing and sound-design software, distribution. And those costs really add up.

So if you want more of this show, more episodes, more exploration of our world through the lens of Freakonomics, now is the time to chip in. Sign up to become a sustaining member, maybe an $8-a-month donation, and you will be joining the other very smart people who already figured out how they want to support a podcast that’s been in their lives for years. Join the Freakonomics Radio team, become a member. Thank you so much.

If I asked you to name the most-trusted profession in America, what would you guess?

MAN: Ohhh. That’s a challenging question.

WOMAN: Wow. I’m too old to trust anybody.

WOMAN: Maybe something in the arts?

No, it’s not something in the arts.

MAN: Hmmm. The most trusted profession in America today?

Right. It’s not politicians. In fact, they’re the least-trusted.

WOMAN: The most trusted profession? I can’t quite answer that.

MAN: This morning we had breakfast at the hotel. And the lady who served the breakfast, she looked very sweet and kind. So I would say that lady.

WOMAN: I would have to say a teacher.

“Teacher” is a pretty good guess. But not the answer we’re looking for.

MAN: The most trusted profession in America? Maybe a doctor?

WOMAN: The most-trusted profession, I would say… nurses. I would say nurses.

Correct! Nurses. For 15 years straight, nurses have topped the Gallup Poll list of professions that Americans say are most honest and ethical. Last year, nurses got an 84 percent approval rating. The next closest: pharmacists, with 67 percent, and then doctors, with 65. Followed by engineers, police officers, and so on, all the way down to journalists (at 23 percent), lawyers (at 18 percent) and, yes, members of Congress (at 8 percent).

So why are nurses ranked so high? For one thing, there’s a good chance you’ve directly interacted with one. There are more than 3.5 million nurses in the U.S.; it’s far and away the most popular medical profession, and one of the most popular occupations overall. So wouldn’t it be nice to be able to measure the effect that nurses have on patient outcomes? Today on Freakonomics Radio: we’ll give it a shot:

Martin HACKMANN: So one key advantage of this study is that we can compare the effect of nurses on patient health.

We’ll hear about a huge boom in one subset of nursing:

Kelly BOOTH: I’m really excited to be a nurse practitioner because I want to make the health care system less broken.

We’ll hear about a national movement that’s reimagining the role of nurses:

Janet CURRIE: The evidence seems to be that increasing accessibility of care in this way is actually getting better outcomes.

But: how this movement is running into a political and regulatory system that’s hard to change.

Uwe REINHARDT: It’s just almost insane. It’s like putting the Mafia in charge of the New York Police Department.

One reason there are so many nurses in the world is that nurses perform so many functions.

Benjamin FRIEDRICH: They have direct patient contact, they provide medication, they monitor the patients, provide counseling …

And yet, despite their prominent role …

FRIEDRICH: Despite their prominent role, their effect on patient health is not fully understood. And so that’s where our paper comes in.

That’s the economist Benjamin Friedrich.

FRIEDRICH: Yes, I’m an assistant professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University.

HACKMANN: Yeah, so I’m an assistant professor of economics at U.C.L.A.

Hackmann and Friedrich make clever use of what might be called an accidental experiment.

FRIEDRICH: So we’re in Denmark in the mid-90s. And basically the economy’s not doing so well; relatively high unemployment.

HACKMANN: And the idea at the time was to bring in some public programs that would rotate the workforce and give opportunities for people that are currently unemployed.

FRIEDRICH: And what the government decides to do is expand their existing parental-leave program and offer up to one year of additional leave of absence to every parent with a child age eight or younger.

One year of extra paid leave, that is.

FRIEDRICH: So parents will receive typically 70 percent of their previous income, and with job security to return to their previous position.

So Denmark was offering a rather generous parental-leave program, including a guaranteed return to your old job.

HACKMANN: So any parent could take advantage.

FRIEDRICH: Yeah, so the point is this reform was not targeted at the health sector at all, right?

HACKMANN: Statistically, though, it’s heavily women that took advantage of it.

FRIEDRICH: So it hits health-care providers completely by surprise.

HACKMANN: And that’s one reason why we see these large effects in the nurse occupation, because 97 percent of nurses are female and that’s one main reason why that occupation was particularly affected by the program.

So the new Danish parental-leave program appealed especially to women, and the nursing sector is almost exclusively female, which meant a lot of nurses took leave. But then — here’s the really important part:

HACKMANN: But then there were no unemployed licensed nurses that could replace them.

That’s right: even though this leave program was designed to ease unemployment, it turns out there weren’t that many unemployed nurses. Certainly not enough to replace all the ones who took a leave.

HACKMANN: And that overall led to an average a reduction in nurse employment of about 12 percent.

So an unintended consequence of this parental-leave program was that the nursing workforce suddenly shrank by 12 percent. The doctor workforce, meanwhile, being mostly male, barely shrank at all. This sudden shortage of nursing care turned out to be exactly the kind of shock to the system that a researcher can exploit to measure cause and effect. In this case, Hackmann and Friedrich wanted to see how the nursing shortage affected health outcomes. They had something else going for them: Denmark, like the rest of Scandinavia, is a bit obsessive about record-keeping, and it collects all sorts of personal data on just about every citizen.

FRIEDRICH: So that means we can observe every individual and whether they take advantage of this leave program.

HACKMANN: So that gives us rich information on employment. And then we have very rich health data.

FRIEDRICH: And we can analyze information about patients in hospitals and nursing homes, so we’ll know hospital admissions, we’ll know diagnoses and treatments.

HACKMANN: We see detailed diagnosis codes, so that allows us to zoom into different hospitals sub-populations. We can compare heart-attack patients. We look at people that have pneumonia. Newborns at risk.

FRIEDRICH: And we’ll know from the death register, for example, the mortality rates of different patient groups. And so we can very specifically say which patients were most affected by the reduction in nurse employment at these different providers.

Okay, so that’s a lot of data on nurses, patients, nursing homes, and hospitals. What’d they find? Let’s start with hospitals:

HACKMANN: We do find negative effects on hospitals.

FRIEDRICH: Yes. So the way we measured it was to look at the 30-day readmission rates.

Readmission rate is a standard measure of hospital care — the idea being that if you have to go back to the hospital after you’re discharged, the original diagnosis and care weren’t so great. On this measure, the economists found the nursing shortage led to a 21 percent increase in readmission for adults and children, and a 45 percent increase for newborns. So nurses would seem to be quite important to overall health outcomes. But if you think that effect is large, consider the data from nursing homes, where nurses play an even more prominent role than in hospitals.

HACKMANN: We see that this reduction in nurses leads to a 13 percent increase in mortality among people aged 85 and older.

FRIEDRICH: Yes. So what we find is that in particular circulatory and respiratory deaths in nursing homes significantly increase.

HACKMANN: To put this roughly into perspective, the parental-leave program reduced the number of nurses by 1,200 in nursing homes persistently and that increased the number of moralities by about 1,700 per year when you consider the 65-year-olds and older, or about 900 people if you look at people aged 85 and older. So these effects are what we think quite large.

Quite large indeed. Which suggests that the returns to nursing are quite high. So, if nothing else, this evidence would seem to justify the fact that nurses consistently win the most-trusted profession competition. But what else should we make of this finding? Imagine you’re a policymaker. You’d think you’d look at this finding and say — well, since nurses are plentiful, and effective, and relatively much cheaper than doctors, perhaps we should think about reassessing and maybe expanding the role nurses play in our health-care system.

Okay, let’s do think about that. For this part of the story, we’ll bring in Freakonomics Radio producer Greg Rosalsky.

ROSALSKY: The story I’m about to tell goes to the heart of the American health care system.

Christy Ford CHAPIN: This very expensive, inefficient model.

ROSALSKY: It’s a story about how political pressures can lead to distorted economics.

REINHARDT: So you should not be surprised that your health spending is double what it is in other countries.

ROSALSKY: And yeah, it’s a story about nurses. But before I start, I should tell you something about myself and nursing. My mom’s a nurse (hi, Mom). My aunt’s a nurse. My sister’s mother-in-law is a nurse. As if all that weren’t enough to make me pro-nurse, then there’s my younger sister.

Alexandra HOBSON: So my name’s Alexandra Hobson. I’m your sister. I’m a registered nurse that’s about to graduate from nurse practitioner school and I’m excited about the graduation that’s coming up soon.

ROSALSKY: Alex is getting her nurse-practitioner doctorate from the University of San Francisco, where she also got her bachelor’s degree in nursing.

HOBSON: So I’ve been a nurse now for six years and I’ve been mainly focused in primary care, because it’s an area that I am passionate about.

ROSALSKY: Primary care — including things like annual checkups and vaccinations — is usually our first line of defense against chronic health problems. Public-health experts say it’s incredibly important, and the medical literature points to a strong relationship between access to primary care and good health outcomes. Studies also show that in many cases, it can save money, since good primary care means catching and treating ailments before they become chronic, and costly. My sister grew passionate about primary care during nursing school.

HOBSON: Because after doing my rotations in the hospital I saw a lot of complications and advanced chronic diseases that I know could be prevented if provided the right preventative services. Without primary-care services, patients usually wait until they have complex illnesses and they end up in the emergency room.

ROSALSKY: Despite the importance of primary care, America suffers from a shortage of doctors who actually provide it. Of the roughly 600,000 practicing physicians in the U.S., only about a third of them work in primary care. This shortage is getting worse, as baby-boomer doctors retire, and since fewer than a quarter of newly minted doctors go into primary care. By 2030, the Association of Medical Colleges projects a potential shortage of more than 40,000 primary-care doctors.

REINHARDT: I think we underpay primary-care physicians and that’s one reason young people don’t go into it.

REINHARDT: I teach health economics, regular economics, and finance at Princeton.

ROSALSKY: Reinhardt says medical students are drawn to higher-paying specialities like plastic surgery and cardiology at the expense of pediatrics, general practice, and other primary-care concentrations. The average specialist earns about 46 percent more than the average primary-care physician. But financial incentives aren’t the only driver.

REINHARDT: It’s an issue of prestige. The culture of the medical school is such that students sort of automatically look up to the specialists and that somehow primary care is kind of viewed as a stepchild.

ROSALSKY: The primary-care gap is increasingly being filled by nurses, like my sister. She worked in a clinic serving Bay Area veterans. While working nearly full-time, she went on to get her masters in public health, and now her doctorate.

HOBSON: Yep, I’m a doctor nurse and proud of it!

ROSALSKY: The nurse practitioner degree, which can be a doctorate or a master’s, requires a lot of training and exams. It leads to a sort of hybrid position, that combines the patient-centered focus of nursing with skills historically reserved for doctors. Like physicians, nurse practitioners, or NP’s, make diagnoses, prescribe medications, order tests and x-rays, and refer patients to specialists. One key difference is the focus and rigor of their training. NPs are required to do hundreds of hours of supervised clinical work and, like my sister, they often spend years in the workforce as a registered nurse before getting their NP degree. But they aren’t required to do a residency, which for doctors is a minimum of three years, typically in a hospital; once in the workforce, their responsibilities vary. For example, in fields involving complex surgeries, NPs assist physicians. But when it comes to primary care, NPs are increasingly taking a leading role.

Surani Hayre KWAN: There are not enough providers to take care of all the patients in the country today.

ROSALSKY: That’s Surani Hayre Kwan, former president of the California Association of Nurse Practitioners, and an NP herself.

KWAN: And everyone is scrambling to figure out how to fix that problem.

ROSALSKY: Between aging baby boomers and the Affordable Care Act, there’s been a huge spike in demand for health care services, especially primary care. But the supply of health care isn’t keeping up. It was a similar imbalance, in the mid-1960’s, that led to the creation of the nurse practitioner profession. The federal government had just created Medicare and Medicaid, which provides health care coverage to the elderly and the poor. The sudden, massive demand for services was not met with a commensurate

Porno Video Hd Korean

Porno Little Teens Pictures

Ftv Upskirt Teen Girls

Katrina Jade New Porn

Feet Hard Porn

Nurses to the rescue: Pandemic changes job descriptions ...

Freakonomics Radio - Nurses to the Rescue! - YouTube

Nurses to the Rescue in Chicago, IL

Nurses To The Rescue 1997