Nipple Areola

⚡ 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Too Short Weak Medium Strong Very Strong Too Long

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

The nipple-areolar complex may be affected by many normal variations in embryologic development and breast maturation as well as by abnormal processes of a benign or malignant nature. Benign processes that may affect the nipple-areolar complex include eczema, duct ectasia, periductal mastitis, adenomas, papillomas, leiomyomas, and abscesses; malignant processes include Paget disease, lymphoma, and invasive and noninvasive breast cancers. Radiologists should be aware of the best methods for evaluating each of these entities: Many disorders of the nipple-areolar complex are unique or differ in important ways from those that occur elsewhere in the breast, and they require a diagnostically specific imaging evaluation. Patients may present with benign developmental variations; inversion, retraction, or enlargement of the nipple, which may have either a benign or a malignant cause; a palpable mass; nipple discharge; skin changes in and around the nipple; infection with resultant nipple changes or a subareolar mass; or abnormal findings at routine mammographic screening. Further diagnostic imaging may include repeat mammography, breast ultrasonography, galactography, and magnetic resonance imaging. When skin changes are present, a clinical evaluation by the patient’s primary care physician, dermatologist, or surgeon should be part of the diagnostic work-up.

After reading this article and taking the test, the reader will be able to:

Describe the normal anatomic variants and abnormal processes that may affect the nipple-areolar complex.

Recognize abnormal imaging features in the nipple-areolar complex.

Describe the clinical and imaging findings of Paget disease of the nipple and the most appropriate methods for managing various phases of the disease.

The nipple-areolar complex may be affected by a broad array of disease processes, many of which have similar appearances; thus, the precise application of clinical and diagnostic skills is necessary for their differentiation and diagnosis. The detection of disorders of the nipple-areolar region may be challenging because of the complex anatomy of this region. A thorough understanding of anatomic variants, benign and pathologic processes, and the imaging features specific to each is the necessary basis for a comprehensive and appropriate imaging assessment, diagnosis, and, if necessary, intervention. In this article, we review normal anatomic variants and benign and malignant processes that may affect the nipple-areolar complex and describe the imaging techniques that are most useful for evaluating this region.

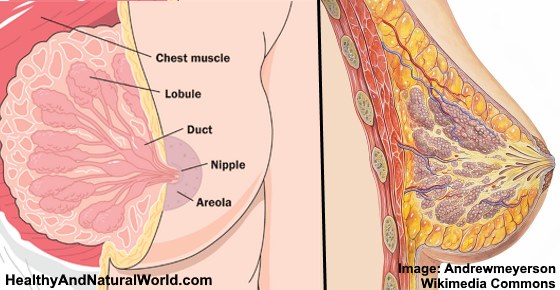

During the 6th week of gestation, paired mammary ridges or milk lines develop on the ventral surface of the embryo, extending from the axilla to the medial thigh. In large part, these milk lines later atrophy; only the part in the pectoral region, where the breasts will develop, remains (,1). The development of the nipple-areolar complex begins in the 12th–16th weeks of gestation, with the differentiation of mesenchymal cells into smooth muscle components. This event is quickly followed by the development of special apocrine glands into the Montgomery glands. In the first stage of glandular development, between eight and 12 mammary ducts form. These ducts are associated with sebaceous glands near the epidermis. Differentiation of the breast parenchyma and development and pigmentation of the nipple-areolar complex begin around the 32nd week and continue to the 40th week (,2). This developmental process is the same for both males and females.

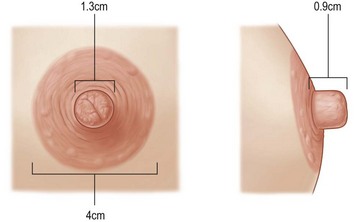

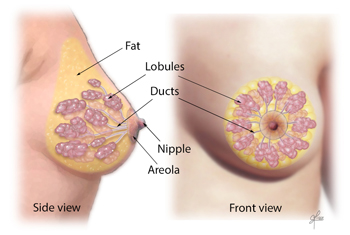

During puberty, the breast mound increases in size. Subsequent enlargement and outward growth of the areola result in a secondary mound (,1). Eventually, the areola subsides to the level of the surrounding breast tissue, leaving a single breast mound (,1). At full development, the nipple-areolar complex overlies the area between the 2nd and 6th ribs, with a location at the level of the 4th intercostal space being typical for a nonpendulous breast. The adult breast consists of approximately 15–20 segments demarcated by mammary ducts that converge at the nipple in a radial arrangement (,Fig 1). Like the number of segments, the number of mammary ducts may vary (,3). The collecting ducts that drain each segment, which typically measure about 2 mm in diameter, coalesce in the subareolar region into lactiferous sinuses approximately 5–8 mm in diameter (,Fig 2). Women occasionally detect a normal lactiferous sinus as a palpable finding at self-examination. In the typical breast, there are 9–20 orifices that drain the segments at the nipple (,3,,4).

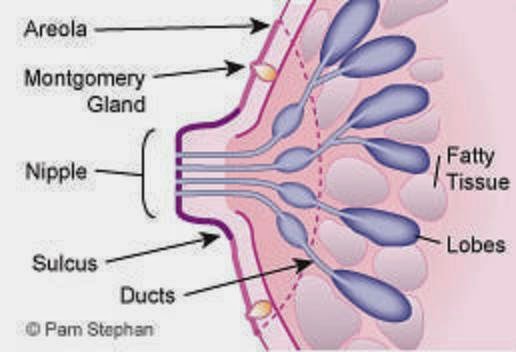

The nipple-areolar complex contains the Montgomery glands, large intermediate-stage sebaceous glands that are embryologically transitional between sweat glands and mammary glands and are capable of secreting milk (,3). The Montgomery glands open at the Morgagni tubercles, which are small (1–2-mm-diameter) raised papules on the areola (,Fig 1) (,5). The nipple-areolar complex also contains many sensory nerve endings, smooth muscle, and an abundant lymphatic system called the subareolar or Sappey plexus. Because the skin of the nipple is continuous with the epithelium of the ducts, cancer of the ducts may spread to the nipple (,3).

There are many possible variants from normal breast development. Knowledge and recognition of these help physicians avoid unnecessary imaging evaluations of benign conditions. The most common abnormal variant, polythelia, occurs when involution of the milk line is incomplete and an accessory nipple or nipples form. Polymastia (formation of an accessory true mammary gland) also may occur when involution of the milk line is incomplete, but it is rare. Accessory nipples and breast tissue most commonly develop in the axilla or inframammary fold, but they may occur anywhere along the embryologic milk line, from the axilla to the groin. Because they are pigmented, accessory nipples may be mistaken for moles.

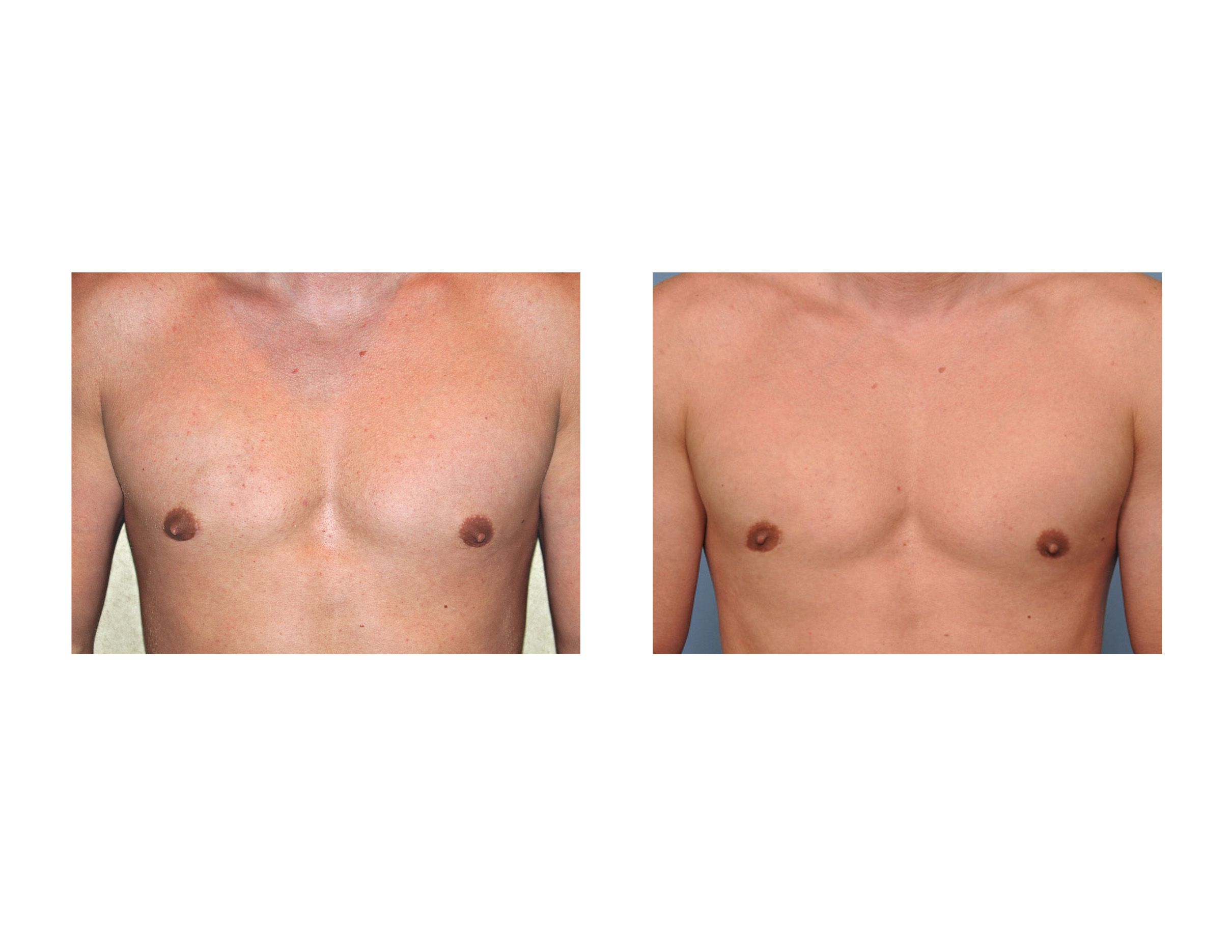

Hypoplasia (underdevelopment of the breast) and amazia (lack of breast tissue, but with the presence of a nipple) are also rare and typically do not affect the appearance of the nipple-areolar complex. Amazia is usually iatrogenic, resulting from surgery or irradiation, whereas amastia (lack of both the breast tissue and the nipple) is congenital. When amastia occurs unilaterally, it is associated with absence of the pectoral muscle; when it occurs bilaterally, it is associated with various other birth defects (,6). If breast development is interrupted at the stage of the secondary mound, the areola will have an appearance that is characteristic of a tuberous breast. Tuberous breasts are defined by reduced parenchymal volume and by herniation of breast parenchyma through the nipple-areolar complex (,Fig 3) (,2,,7).

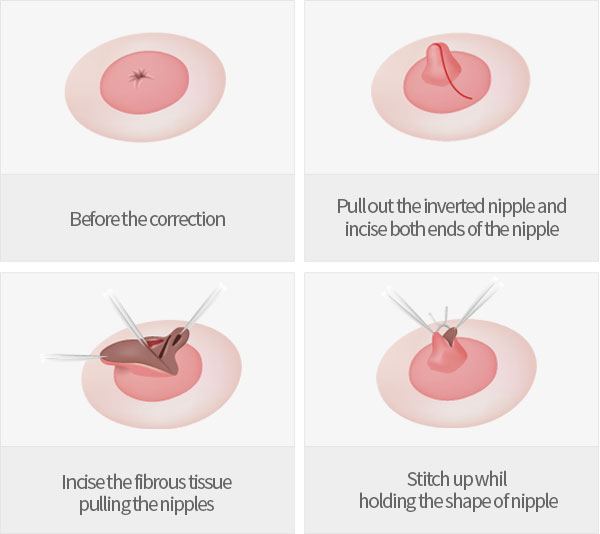

The terms retraction and inversion often are used interchangeably, but such usage is inexact. Retraction is properly applied when only a slitlike area is pulled inward (,Fig 4,,), whereas inversion applies to cases in which the entire nipple is pulled inward—occasionally, far enough to lie below the surface of the breast (,Figs 5,, ,6,,) (,8). Both retraction and inversion may be either congenital or acquired and either unilateral or bilateral. Bilateral and slowly progressive or long-standing nipple retraction is likely benign and may be a normal variant. A woman with an acquired unilateral nipple inversion may have an underlying malignancy or inflammatory condition and should undergo evaluation with mammography and possibly US or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (,Fig 6,,). The differential diagnosis in a case of acquired nipple retraction or inversion includes inflammatory conditions such as duct ectasia (common), periductal mastitis, and tuberculosis, as well as malignancy (,8). Central, symmetric, slitlike retraction usually indicates a benign process (,Fig 4,,), whereas inversion of the whole nipple with distortion of the areola is typically a result of malignancy (,Fig 6,,) (,8).

The nipple may be mistaken for a mass both at mammography and at MR imaging. To prevent such an event, the nipple should be positioned in profile on at least one mammographic view (,9). If the source of an apparent mass is questionable and the nipple is not visible in profile, doubts may be laid to rest by placing a BB on the nipple and repeating the mammographic acquisition with the nipple in profile (,Fig 7,). Keeping the nipple in profile and applying appropriate imaging techniques also helps improve the detection of retroareolar masses (,Fig 6,,). The retroareolar region is a challenging location in which to detect a mass, and oblique positioning of the nipple or underexposure of the image may obscure a significant finding (,10). Clinical examination is more sensitive than mammography for the detection of subareolar or central (within 2 cm of the nipple) cancers (,11). Approximately 8% of breast cancers arise in the subareolar region (,12), and these cancers are usually palpable (,10). If a patient presents with a palpable mass behind the nipple, spot compression views may better demonstrate the mass than routine mammographic images.

During US evaluation of a subareolar abnormality, a standoff pad moves the finding into the focal zone of the ultrasound beam (about 1.5 cm) and improves the detectability of a mass (,13). On US images, the nipple often is depicted with posterior acoustic shadowing, which likely is due to the fibrous composition of nipple tissue and the confluence of multiple structures with interfaces.

The use of a standoff pad helps remove shadowing caused by air trapped in the crevices within the raised nipple. The use of copious amounts of US gel with various compression techniques, described by Stavros (,13), also may help improve the detection of clinically significant lesions located near or in the nipple.

The normal nipple may have various imaging appearances on MR images obtained after the administration of contrast material (,Fig 8,). Normal nipples typically are surrounded by a smooth thin rim of enhancement and appear symmetric bilaterally (,14). This characteristic appearance is maintained even if a nipple is retracted or inverted. However, the area of enhancement surrounding an inverted nipple in the subareolar position may cause it to be mistaken for a mass (,Fig 5,). Comparison of the appearance of both breasts and correlation of the areas of enhancement in two intersecting mammographic planes may help confirm that the finding is an inverted nipple and not a clinically significant lesion. The normal nipple also may not enhance in some patients.

Skin lesions on the areola also may resemble masses. Identifying a superficial skin lesion or skin tag with a metallic marker before performing mammography may help clarify the nature of an apparent mass and help avoid unnecessary further imaging and other diagnostic evaluations (,Fig 9,).

Calcifications may develop in the nipple-areolar complex in some patients and typically are benign (,Fig 10,) (,15,,16). Calcifications may occur in the skin of the areola, within the Montgomery glands, within hair follicles, in association with a mass, or in the context of Paget disease. Calcifications in the skin of the areola may be secondary to surgery such as reduction mammoplasty (,Fig 11) but also may occur in patients without a history of such surgery. Occurrences of calcified cutaneous horns, conical projections of keratin above the skin surface in the nipple-areolar complex, also have been described (,16). Cutaneous horns are typically asymptomatic and benign but also have been associated with malignant lesions, including Paget disease and squamous cell carcinoma (,17,,18).

Both benign and malignant processes may produce visible changes in the skin of the nipple, including erythema, scaling, crusting, fissures, vesicles, erosions, lichenification, or some combination of these. These changes may be accompanied by pain or itching (,19). Correct diagnosis of the underlying pathologic process is important because of the possibility of a breast malignancy (,20). A negative result at cytologic analysis of an associated discharge may be inaccurate (,21), and the imaging appearance may be normal. The clinical history may be helpful, but histologic analysis of a biopsy specimen often is necessary for accurate diagnosis.

Eczema of the nipple-areolar complex typically occurs bilaterally (,Fig 12) and may be associated with systemic symptoms of atopic dermatitis, including (but not limited to) flexural dermatitis (,22). Eczema is responsive to topical application of a moderate-dose steroid cream. However, if the symptoms do not improve, a biopsy may be necessary to exclude Paget disease of the nipple, which may have a similar appearance.

Psoriasis also may cause nipple changes, including excoriation and ulceration (,23). A complete clinical history may be helpful for differential diagnosis, as patients may have other manifestations of disease. Other benign processes that occasionally cause similar changes in the nipple include allergic contact dermatitis, irritant dermatitis (so-called jogger’s nipple), lichen simplex chronicus, and Candida infection (which typically occurs in lactating women) (,24).

In addition, two rare conditions of the nipple-areolar complex may be seen: nevoid hyperkeratosis, a benign idiopathic condition that is characterized by slowly growing verrucous thickening and hyperpigmentation of the nipple, areola, or both (,25); and periareolar fistula, an extraintestinal cutaneous manifestation of Crohn disease (,26). The latter diagnosis should be considered when a lesion initially thought to be a breast abscess is not controlled with antibiotics.

Paget disease of the nipple-areolar complex is characterized by the presence of neoplastic cells in the epidermis. It is most often associated with underlying ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and rarely with invasive ductal cancer (,27). Paget disease is typically suspected on the basis of specific clinical manifestations, particularly if the skin changes are unilateral and associated with a breast mass, breast calcifications, or a nipple discharge. The gamut of skin changes may range from mild to severe, with a variety of appearances including nipple erythema, scaliness, erosion, ulceration, and fissures (,Fig 13,,,,,). When an underlying invasive breast cancer is present, the physical manifestations may include skin retraction, skin thickening, or a palpable mass. When these signs are evident and Paget disease is suspected, imaging should be performed to detect the underlying carcinoma.

A mammogram may depict a mass or calcification representative of invasive cancer or DCIS, respectively. However, mammographic findings in some patients with breast cancer and Paget disease are normal (,28). In one study, breast cancer was occult at mammography in 15% of 52 patients with Paget disease and at both mammography and US in 13% of those patients (,28). US depicts changes within the nipple or immediately deep to it in a few patients with Paget disease; however, the findings are nonspecific and resemble those in cases of infection. US images may reveal parenchymal heterogeneousness, hypoechoic areas, discrete masses, skin thickening, or dilated ducts (,28). In patients in whom the mammographic findings are normal or the extent of disease is uncertain, MR imaging may show abnormal nipple enhancement, thickening of the nipple-areolar complex, an associated enhancing DCIS or invasive tumor, or a combination of these (,29–,31).

Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) is an additional possibility when a patient presents with an itchy and scaly nipple. However, squamous cell carcinoma is only rarely found in the nipple-areolar complex. Bowen disease cannot be clinically differentiated from Paget disease, and a biopsy is necessary for diagnosis (,32).

Masses of the nipple and the underlying subareolar ducts are most commonly benign (,Figs 14,, ,15,). The differential diagnosis of such masses includes papilloma, adenoma, fibroadenoma, and complicated cyst (fibrocystic changes). Patients may present with a palpable lump, visible infection, or nipple discharge, or a mass may be clinically occult and detected only at screening. When clinical symptoms are present and findings at routine mammography are normal, it may be necessary to perform spot compression mammography, US, galactography, or MR imaging to localize and diagnose the cause of symptoms. The lesions may enhance and may be associated with an abnormal dilated and fluid-filled duct on MR images (,Figs 16,, ,17,,,).

Benign lesions include cysts, fibroadenomas, adenomas, papillomas (,Figs 15,–,,,17,,,), galactoceles, abscesses (,Fig 18,), leiomyomas, and, more rarely, nodular mucinosis (,33) and spindle cell proliferation like that seen in fibrous histiocytoma (,34). It may be difficult to differentiate the most common of these entities from one another, as their imaging features are similar and nonspecific; therefore, a biopsy may be necessary for diagnosis. The clinical history may be helpful: Papillomas may manifest with a nipple discharge (,35); abscesses may be associated with redness, swelling, and pain; and fibrous histiocytoma–like spindle cell proliferation may occur after nipple piercing (,36). Morphologic features also are helpful for narrowing the differential diagnosis of a mass in the nipple-areolar complex: Papillomas, adenomas, and leiomyomas are typically oval and circumscribed, whereas abscesses and fibrous lesions are more commonly ill defined.

Abscesses may have an appearance that arouses suspicion, with an irregular shape, ill-defined or spiculated margins, high density at mammography, and a central region of hypoechogenicity with a thick echogenic rim at US (,Fig 18,). The imaging features of an abscess are difficult to differentiate from those of a breast carcinoma. The differential diagnosis of nonpuerperal breast abscesses includes chronic recurrent subareolar breast abscess, inflammatory breast cancer, cystic breast disease, duct ectasia, and fat necrosis (,37). The clinical manifestation and past medical history may be helpful, but symptoms may be minimal. Patients who are presumed to have an infection should undergo follow-up imaging evaluations to exclude a malignancy until the appearance of the region returns to normal. It is noteworthy that lymph nodes may be enlarged in the presence of either m

3d Handjob Cartoon

Porn Funny Moments

Mistress Melanie

Anal Hole Dildo

No Gag Reflex Throatdown

Areola - Wikipedia

Nipple and Areolar Changes: What's Normal, What's Not

Nipple-Areolar Complex: Normal Anatomy and Benign and ...

Parts of a Nipple, Areola, and Montgomery Glands

Common and Unusual Diseases of the Nipple-Areolar Complex ...

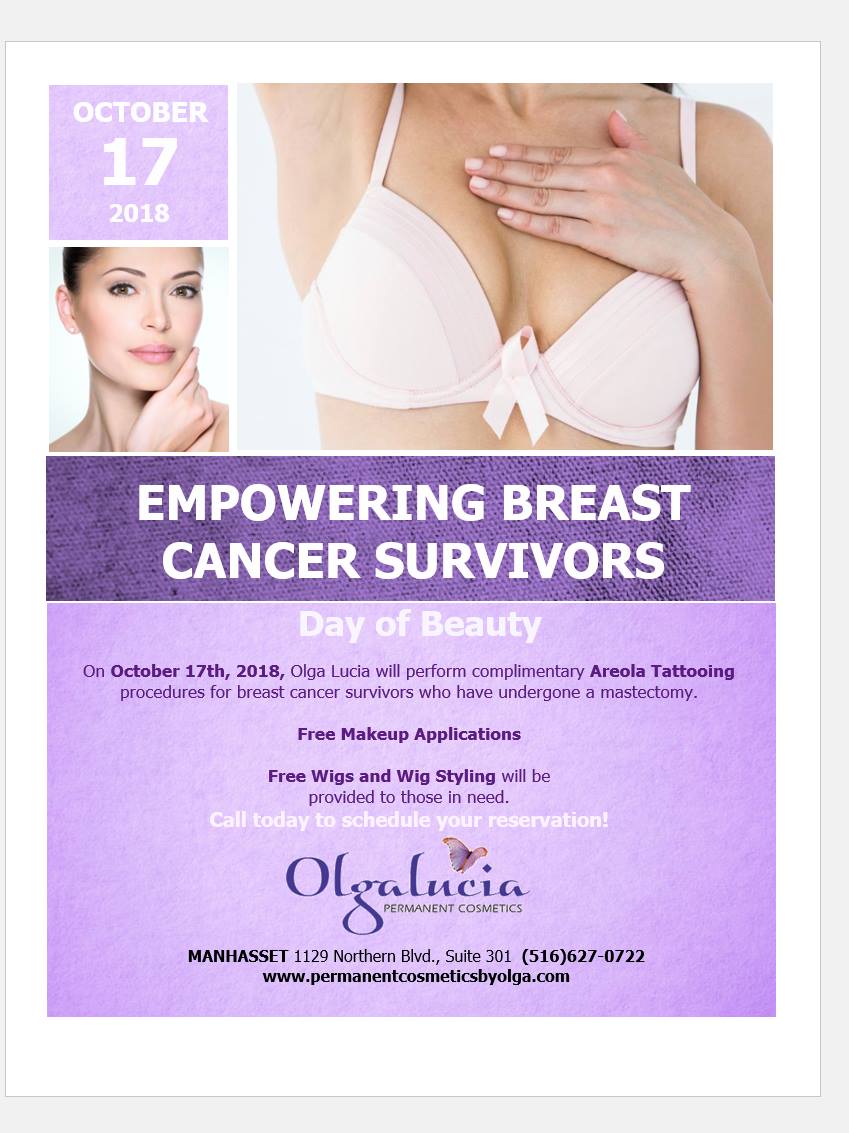

What Are Areola Tattoos? The Ultimate Guide to Nipple ...

The 8 Nipple Types in the World - Different Areola Sizes ...

3D AREOLA/NIPPLE PIGMENTATION - Avarte Micro…

Areola + Nipple Reconstruction | MicroBladers Studio ...

Areola | Luton | 3D Areola Tattoos - The permanent solution

Nipple Areola

/female-breast-anatomy--illustration-769724385-964156769b2a423497ad992305a01ac2.jpg)

/breast-56c501725f9b58e9f32fa57e.jpg)