New tool: Mess with DNS! - Julia Evans

Julia EvansHello! I’ve been thinking about how to explain DNS a bunch in the last year.

I like to learn in a very hands-on way. And so when I write a zine, I oftenclose the zine by saying something like “… and the best way to learn moreabout this is to play around and experiment!“.

So I built a site where you can do experiments with DNS called Mess With DNS. It has examples of experiments you can try, andyou’ve very encouraged to come up with your own experiments.

In this post I’ll talk about why I made this, how it works, and give youprobably more details than you want to know about how I built it (design, testing,security, writing an authoritative nameserver, live streaming updates, etc)

a screencast

Here’s a GIF screencast of what it looks like to use it:

it’s a real DNS server

First: Mess With DNS gives you a real subdomain, and it’s running a real DNSserver (the address is mess-with-dns1.wizardzines.com). The interesting thing about DNSis that it’s a global system with many different computers interacting, and soI wanted people to be able to actually see that system in action.

problems with experimenting with DNS

So, what makes it hard to experiment with DNS?

- You might not be comfortable creating test DNS records on your domain (or you might not even have a domain!)

- A lot of the DNS queries happening behind the scenes are invisible to you. This makes it harder to understand what’s going on.

- You might not know which experiments to do to get interesting/surprising results

Mess With DNS:

- Gives you a free subdomain you can use do to DNS experiments (like

ocean7.messwithdns.com) - Shows you a live stream of all DNS queries coming in for records on your subdomain (a “behind the scenes” view)

- Has a list of experiments to try (but you can and should do any experiment you want :) )

There are three kinds of experiments you can try in Mess With DNS: “weird” experiments, “useful” experiments, and “tutorial” experiments.

the “weird” experiments

When I experiment, I like to break things. I learn a lot more from seeing whathappens when things go wrong than from things going right.

So when thinking about experiments, I thought about things that have gone wrong for me with DNS, like:

- negative DNS caching making me wait an HOUR for my website to work just because I visited the page by accident

- having to wait a long time for cached record expire

- different resolvers having different cached records, which meant I got different results

- pointing at the correct IP address, but having the server not recognize the

Hostheader

Instead of viewing these as frustrating, I thought – I’ll make these into aninteresting experiment with no consequences, that people can learn from! So webuilt a section of “Weird Experiments” where you can intentionally cause someof these problems and see how they play out.

the “useful” and “tutorial” experiments

The “weird” experiments are the ones we spent the most time on, but there arealso:

- “tutorial” experiments that walk you through setting some basic DNS records,if you’re newer to DNS or just to help you see how the site works

- “useful” experiments that let actual realistic DNS tasks (like setting up a website or email)

I think I’ll add more examples of “useful” experiments later.

the experiments have different results for different people

One thing we noticed in playtesting was that the “weird” experiments don’t havethe same results for everyone, mostly because different people are usingdifferent DNS resolvers. For example, there’s a negative caching experimentcalled “Visit a domain before creating its DNS record”. And when I test thatexperiment, it works as described. But my friend who was using Cloudflare(1.1.1.1) as a DNS resolver got totally different results when he tried it!

I was stressed out by this at first – it would for sure be simpler for me if Iknew that everyone has a consistent experience! But, thinking about it more,one of the basic facts about DNS is that people don’t have a consistentexperience of it. So I think it’s better to just be honest about that reality.

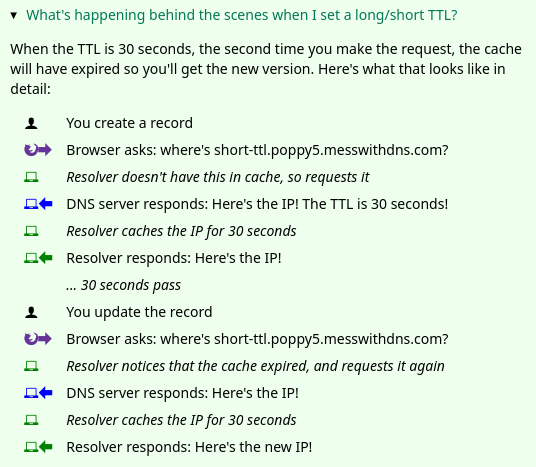

giving “behind the scenes” explanations

For some of the experiments, it’s not really obvious what’s happening behindthe scenes and I wanted to provide explanations at the end.

I often make comic to show how different computers interact. But I didn’t feellike drawing a bunch of comics (it takes a long time, and they’re hard toedit).

So we came up with this format for showing how the different characters interact,using icons to identify each character. It looks like this:

Honestly I think this could probably be made clearer and I don’t love thedesign of the icons, but maybe I’ll improve it later :)

Okay, that’s everything I have to say about the experiments.

design is hard

Next, I want to talk about is the website’s design, which was a challenge for me.

I built this project with Marie Claire LeBlanc Flanagan, a friend of mine who’s a game designerand who thinks a lot about learning. We pair programmed on writing all theexperiments, the design and the CSS.

I used to think that design is about how things look – that websitesshould look nice. But every time I talk to someone who’s better at design thanme, the first question they always ask instead is “okay, how should thiswork?“. It’s all about functionality and clarity.

Of course, the site isn’t perfect – it could probably be more clear! But wedefinitely improved it along the way. So I want to talk about how wemade the website more clear by doing user testing.

user testing is incredibly helpful

The way we did user testing was to observe a few people using the websiteand get them to narrate their thoughts out loud and see what’s confusing tothem.

We did 5 of these tests (thanks so much to Kamal, Aaron, Ari, Anton, and Tom!).We came out of each test with like 50 bullet points of notes and possible things to change, and then we needed to distill them into actual changes to make.Here are 3 things we improved because of the user testing:

1. the sidebar

One thing we noticed was – we had this sidebar with experiments people couldtry. It looked like this, and I originally thought it was okay.

But in the user testing, we saw that people kept getting confused and lost inthe sidebar. I really didn’t know how to improve it, but luckily Marie isbetter at this than me and we came up with a different design thatbetter isolates the information about each experiment. Here’s a gif:

Also, everything in that gif implemented in pure CSS with a

2. the terminology

Another thing we learned in user experience testing was that a lot of peoplewere confused about the DNS terms we were using like “A record” or “resolver”.So we wrote a short DNS dictionary to try to help with that a bit.

3. the instructions

Originally, in the instructions I’d written something like

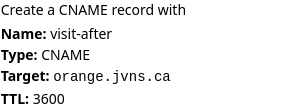

Create a CNAME record that points visit-after.fox3.messwithdns.com at orange.jvns.ca with a TTL of 3600

In the playtesting, we noticed that people took a long time to parse thatsentence and translate it into which fields they needed to fill in. So wechanged the instructions to look like this instead:

That feels a lot clearer to me.

That’s all I’ll say about the design, let’s move on to the implementation.

frontend test automation is amazing

Even though it’s pretty small, this is a bigger Javascript project than I’vedone previously. Usually my testing strategy for Javascript is “write a bunchof terrible untested code, manually test it, hope for the best”.

But when taking that approach this time, I kept breaking the site and I gota familiar feeling of “JULIA, you need to write TESTS, come on, this isridiculous”.

I know about frontend test automation frameworks like Selenium, but I hadn’tused them for ages. I asked Tom what I should use, he suggested Playwright, so I used that and it worked great.

All of the Playwright tests are integration tests which is really helpful –even though it’s a frontend testing framework, the integration tests havehelped me find a bunch of bugs on the backend too.

Here’s an example of one of my tests, that makes sure that when I make a DNSrequest to the backend it appears in the frontend. (This one broke just theother day when I was refactoring the backend!)

test('empty dns request gets streamed', async ({ page }) => { await page.goto('http://localhost:8080') await page.click('#start-experimenting'); const subdomain = await getSubdomain(page); const fullName = 'asdf.' + subdomain + '.messwithdns.com.' await getIp(fullName); await expect(page.locator('.request-name')).toHaveText(fullName); await expect(page.locator('.request-host')).toHaveText('localhost.lan.'); await expect(page.locator('.request-response')).toContainText('Code: NXDOMAIN');});I won’t really explain the details but hopefully that gives you a basic idea.These tests are still a little flaky for reasons I don’t quite understand, butI think maybe that’s normal with frontend automation? I’ve found them pretty easyto write, pretty reliable, and super useful.

Okay, now let’s move to talking about the backend, which was more in my comfortzone. This was fun to build and there were a bunch of things I thought were interesting.

I’ve put a snapshot of the backend’s code on GitHub if you want to read it.

the authoritative DNS server

I needed to write an authoritative DNS server, and I took my usual approachwhen trying to do something I haven’t done before:

- start with an empty program that does almost nothing (copied from How to write a DNS server in Go)

- read 0 documentation and just start implementing stuff

- see what breaks

- Begrudgingly read a little bit of documentation to fix things that break

I used this wonderful DNS libraryhttps://github.com/miekg/dns which I used previously for the backend ofhttps://dns-lookup.jvns.ca/.

Here’s what my main ServeDNS function looks like, with some error handling and logging removed:

func (handle *handler) ServeDNS(w dns.ResponseWriter, request *dns.Msg) { // look up records in the databasemsg := dnsResponse(handle.db, request)w.WriteMsg(msg) // Save the request to the database and send it to any clients who have a websocket openremote_addr := w.RemoteAddr().(*net.UDPAddr).IPLogRequest(handle.db, r, msg, remote_addr, lookupHost(handle.ipRanges, remote_addr))}following the DNS RFCs? not exactly

I think I’m doing a pretty bad of following the DNS RFCs. Basically my algorithm for which records to return is:

for which DNS response code to return:

- return

NXDOMAINif I don’t have any records for a name, andNOERRORif I do have a record - return a

REFUSEDerror if someone requests a name that doesn’t end with.messwithdns.com. - return

SERVFAILif I run into some kind of error like not being able to

for which queries to return:

- if I have a

CNAMErecord for a name, then return it no matter what query type is requested - if I get a

HTTPSquery, return any A/AAAA records I have. (I’m doingthis because it’s what Cloudflare seems to do and I get a lot of HTTPS DNSqueries, I spent a few minutes trying to read the IETF draft about whatHTTPS queries are and I couldn’t really understand it so I gave up) - otherwise just return any records that match the requested type

Hopefully that’s close enough that it won’t cause any major problems. I thinkthere are some rules I’m not following, like if there’s already an A recordfor a name I’m not supposed to let people set a CNAME record. But I’m lazy soI did not implement that.

I did find this test suite for an authoritative DNS server which I might spend more time looking through later.

live streaming the requests with websockets and Go channels

I wanted people to be able to livestream all requests coming in for theirdomain. When I was first thinking about how this works, I started googlingthings like “firebase” and “google pubsub” and “redis” and other pub/sub orstreaming systems. I started implementing it this way but then I was havingtrouble getting it to work and I thought… wait… I don’t want to deal with aseparate service!

So instead I wrote60ish lines of code using Go channels (stream.go).Basically every time someone opens a websocket, I create a Go channeland store it in a map. Then whenever a DNS request comes in, I can just send itto all the channels that are waiting for requests.

This seems to work great. Originally I was using SSE (server side events)instead of websockets, but for some reason it wasn’t working on one friend’scomputer so I switched to websockets and that seems more reliable.

tradeoff: no distributed systems, but slower response times

Implementing my pub/sub system with Go channels means that both the DNS serverand the HTTP server need to live in a single process, and so I can’t runmultiple DNS servers.

Right now the single process is in Virginia, so that means the HTTP API and DNSresponses are going to be slower if you’re in Tokyo or something. I decidedthis was okay because it’s an educational site – it’s ok if it’s a littleslow!

And this means I don’t need to deal with any distributed systems, which isamazing. Distributed systems are very annoying.

The static files for the frontend are distributed though: I put the site behind a CDN which should helpmake everything feel faster.

finding out who owns IP addresses with an ASN database

When a DNS requests comes in, it comes from an IP address. I wanted to tellusers who owns that IP address (Google? Cloudflare? their ISP?). The obvious way is to do a reverse DNS lookup.But what if that doesn’t work?

I started out by using an API to look up the owner of an IP. Thisworked great, but then, similarly to with the pub/sub question, I thoought –why rely on an external service? I bet I can do this myself without taking adependency on an API that might go down.

So I googled “asn database download”, and I found this free IP to ASN database which lists every IP address and who it belongs to.

Then I just needed to implement a binary search(well, technically it was mostly Github Copilot that implemented a binary search, I just fixed the bugs), and I could look upthe owner of any IP super quickly.

So the IP address lookup code does a reverse DNS lookup and then falls back to the ASN database.

some notes on picking a database

I started out using planetscale because they have a free tier and I love free tiers.

But then I realized that my application is very write-heavy (I do a databasewrite every time a DNS request comes in!!), and their free tier only allows 10million writes per month. Which seemed like a lot initially, but I’d alreadygotten 100,000 DNS queries while it was only me using the service, and suddenly10 million really wasn’t feeling like that much.

So I switched to using a small Postgres instance with a 10GB volume. I thinkthat should be a reasonable amount of disk space because even though I store alot of requests, I don’t actually need to store the requests for that long –I could easily clear out old requests every hour and it probably wouldn’t makea difference.

The data volume is attached to a stateless machine running Postgres that I can easily upgrade togive it more CPU/RAM if I need to.

I’m also excited about using Postgres because my partner Kamal has a lot moreexperience using Postgres than me so I can ask him questions.

let’s talk about security

Like with the nginx playground, Ihad some security concerns. When I started building the project, I set it up sothat anybody could set any DNS record on any subdomain of messwithdns.com.This felt a little scary to me, though I couldn’t put my finger on exactly whyinitially.

Then I implemented Github OAuth, but that felt kind of bad too – logging in addsfriction! Not everyone has a GitHub account!

Eventually I chatted with Kamal about it and we decided I was concerned about 3 things:

- Accidental collisions where 2 people get assigned the same subdomain and get confused

- People trying to create phishing subdomains

- I wnated people to get short, easy-to-type in domains

So I wrote a simple login function that:

- Generates a random subdomain like

ocean8that’s never been used before - Saves

ocean8to a database table so nobody else can take it - Sends a secure cookie to the client (using

gorilla/securecookie) - Then the user (you!) can make any changes you want to

ocean8.messwithdns.com.

Also the website’s domain (https://messwithdns.net)is hosted on a different domain entirely than the domain where users can setrecords (which is https://messwithdns.com). So that means that if someone somehow does set a record on messwithdns.com at least it won’t take the site down.

some static IP addresses

One more quick note about the experiments: I wanted to have some IP addresses people could use in their experiment if theywanted. So I set up two static IPv4 addresses: orange.jvns.caand purple.jvns.ca. They show a picture of an orange and somegrapes respectively, so you can easily see which is which.

It’s important that each one has a dedicated IP address because they’ll beaccessed using a bunch of different domains, so I couldn’t use the domain nameto decide how to route the request.

that’s all

I hope this project helps some of you understand DNS better, and I’d love tohear about any problems you run into. Again, the site is athttps://messwithdns.net and you can report problems on GitHub.

本文章由 flowerss 抓取自RSS,版权归源站点所有。