Never Tell Our Business to Strangers

@americanwords

Nine years ago, when my mother suffered a minor heart attack, my father and I learned that for more than two decades she had been lying about her age. She was actually three years older than my father, not two years younger, as she had always said. Apparently sensing that her real age might be relevant to her treatment, she had given the nurse her actual birth date, and then my father and I saw it scrawled on her plastic hospital bracelet.

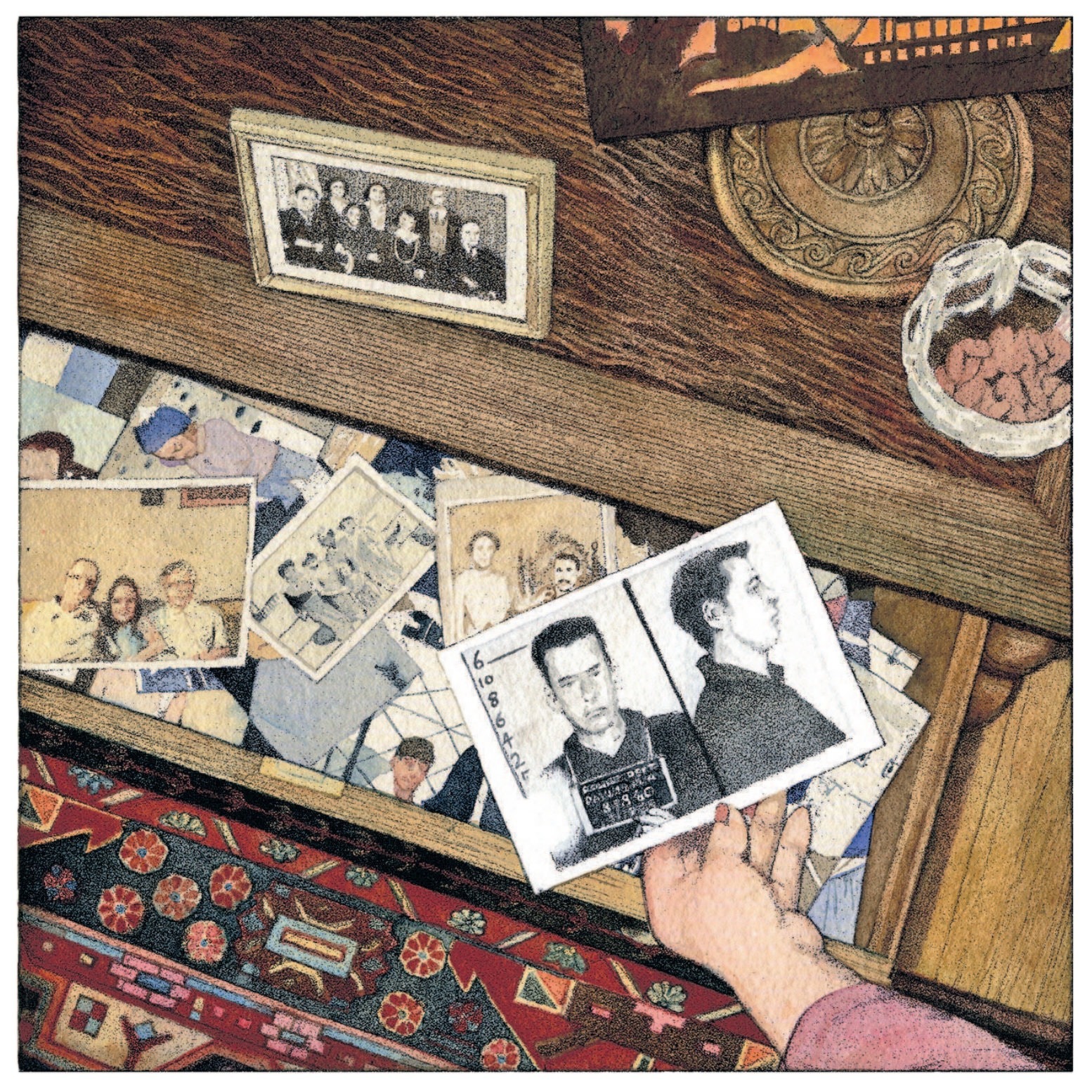

That my mother had maintained this deception for so long shouldn’t have surprised me. My parents were all about deception on a grand scale: false identities, hidden pasts, dark deeds. As an only child, I was mostly isolated with my parents throughout my childhood as we crisscrossed the country, went bankrupt three times and had run-ins with the law.

It was not a normal childhood, but what did I know of normal? My parents were my whole world, and I loved them. I was especially devoted to my father, who showered me with attention, sneaking candy under my pillow that my mother had forbidden me to eat.

It wasn’t until I was an adult and discovered just how dark their past was that my love and loyalty were severely tested. And I’m still not sure what to make of the scattered truths and fictions that define who I am today.

For me, our story began when I was 5 years old and the F.B.I. came for my father. We were living in Irvine, Calif., where he had a small carpet-cleaning business. My older cousin happened to be visiting from Florida, and my mother told her to keep me in my bedroom as the agents arrested my father. It was a harrowing ordeal; distraught, I rushed my bedroom door time and again, trying to get to my father as my cousin restrained me.

What had he done? My mother first told me they had mistaken him for someone with the same name. (And there is, in fact, an organized crime figure with his name.) After his arrest led to his detention, however, my mother conceded that he’d done something wrong, but she wouldn’t tell me what.

Regardless, our lives were turned upside down. The F.B.I. took my father to New York, and my mother followed to arrange for his defense, while I was sent to live with my aunt in North Miami Beach. A parade of character witnesses testifying to my father’s honest work as a carpet cleaner finally led to his release a year later.

I didn’t learn of his release until my parents showed up in Florida on my aunt’s doorstep, which was the best surprise I have ever received and remains my fondest memory of my parents. I was 6 years old.

We stayed in Florida for a few months until my father, who had gotten a job as a line cook, could save enough money to take us back to California. When we returned, we kept on the move, living over the years in Garden Grove, El Toro, Lake Forest, Mission Viejo, Laguna Hills, Aliso Viejo and Laguna Niguel. The nature of our cocoonlike existence led me to trust only my parents, to look only to them to tell me who I was and to feel fearful and disloyal for seeking outside comfort. My parents’ mantra, drilled into me, was, “Never tell our business to strangers.” And I didn’t.

But I wasn’t even sure who we were or what our business was. Until I was 5, I knew our last name to be Cassese, but then my parents told me our real last name was Mascia. Cassese was the surname of a prison buddy of my father’s. I knew my father both as John, his real name, and Frank, his father’s. During our brief time in Houston, he had apparently gone by Nicholas.

The day after I graduated from high school, we packed our belongings into a U-Haul and moved to New York, where my father had friends who could get him work. He joined a painting crew, earning $100 a day, leaving my mother and me with nothing to do for the summer but drive around Long Island in a car that was soon to be repossessed, talking. After one of these drives, I broke down in tears, recalling the anguish of the day my father was arrested. “I deserve to know what happened,” I told her.

At my insistence, she finally opened up. She began by telling me the real story of how she and my father met, which was not “through friends,” as had been their story, but at the Fishkill Correctional Facility in New York, where my father had been incarcerated for “racketeering.” My mother was a high school English teacher with a humanitarian bent, who visited prisons, hoping to write a book about the prison reform movement. My father was among the inmates she interviewed.

Their interviews gave way to animal attraction, and when my father was paroled a few months later, they started dating. Within a year they married and moved from New York to Miami, so he could escape his previous life of crime. But after I was born, he went back to his old partners and their sources of income: bulk marijuana and cocaine sales in the Port of Miami.

When I was a year old, my father was arrested on cocaine possession charges. The authorities didn’t yet know he had violated his parole and mistakenly let him out on bail. And the second my parents stepped outside, my father said to my mother, “If we stay here, I’m going to end up dead or in jail. I’m running. You coming?”

“Of course,” she answered. It would prove to be the defining moment of her life, and mine.

And so, as she explained, it was that act — skipping out on bail and then crossing state lines — that led to my father’s being arrested by the F.B.I. in California five years later.

Which was the truth, but not, as it turned out, the whole truth.

A year after my mother and I had this conversation, when I was in college, I read a newspaper article about a woman who had searched an online database for criminals who had been shuffled through the New York State Corrections Department. One afternoon I found the site and typed my father’s last name into the search field. His record appeared, and I was able to verify that it was the right John Mascia. The birth date matched. I scrolled down the page past his identification number to a table listing “crimes of conviction.” And there it was, the real act that had bound the three of us together.

Murder.

I sat silently as my center seemed to drop through the floor.

By then my father was dying of lung cancer, and in his remaining time I never told him what I had learned. For my whole life he had tried to protect me from his darkest secret, and I didn’t feel able to broach it with him now.

It took me days to confront my mother, who mostly reacted with concern that my father’s awful past was available to anyone with a modem.

A year later my father died. At the memorial service I stood and eulogized him, declaring: “My parents and I are soul mates. We are cut from the same cloth, and nothing, not even death, can change what we mean to each other. The type of bond we have transcends death. It exists, even today, even in this very room.”

I meant it. But what I didn’t fully appreciate then was that my parents were the true soul mates, bound by ugly crimes. As a child, I had always felt their united front against the world — and sometimes me — but I didn’t know why until last winter, when my mother had a stroke and was close to dying herself. When she emerged from her haze, she somehow felt compelled to tell me the rest. “Your father did some bad things after he got out of jail, Jenny.”

No. Was it possible he had repeated the crime that put him away in the 1960s and ’70s? “Tell me,” I said. “Was it...?”

She nodded.

“How many?”

“Four, maybe five,” she said sheepishly.

I was reeling.

“It was after you were born,” she continued. “It was a part of that life. He was doing a job, and one of the byproducts of that job was to do what he did.” She went on to explain that his victims were fellow drug dealers, as if that made it more palatable.

No matter. The horror of my father’s legacy was too much to bear. I fled, sobbing. Nineteen days later, my mother suffered a heart attack and died.

I never reported my mother’s rambling deathbed confession to anyone. I knew so little. The crimes, if true, were more than 25 years old. My parents were gone, and I wanted their past buried with them. Or so I told myself.

I have since marveled at my mother’s choice to stay with my father and to defend him, though, of course, I loved him, too, albeit in ignorance. He and my mother were all I had, and although my mother was deceitful and overbearing, she was also my best friend. If I didn’t tell her about something, it felt as if it hadn’t happened.

In her final days, after the heart attack had sapped her strength and left her nearly brain dead, I ducked into a bathroom in the intensive care unit and saw myself in the mirror, and that’s when I felt it. Not a crack, but a slow tearing of the fiber that connected us. I stood in the unforgiving fluorescent glow, and I saw that for the first time I was standing alone. I was 28, and I could no longer look to my parents to tell me who I was. I had outlived their past, and now it was up to me to create a new future.

The bad was still with me, of course, but so was the good. A few days after my mother’s death, I was snooping on her computer and found three unnotarized wills languishing among various e-mail messages and letters she had saved. In each she gave me detailed instructions on how to extract cash advances from her credit cards, betraying her larcenous streak to the end. After those instructions, to my utter surprise, was this:

“Dear Jenny: I loved you very much. I was astonished that at my age I could have had such a lovely, funny, beautiful child. Your father and I both loved you very much. I hope you know this, that in spite of imagined or real hurts, and all the times we were separated or fought with you or with each other, that we showed you that love. We three were a family, a real one that sat down to dinner together, and explored and traveled together, even if we didn’t go to the Grand Canyon.

“Wherever I am, even though I am not a believer, I know that part of me will belong to this earth somewhere. And thus part of the earth will always remember and love you.”