NATIVE AMERICANS IN UNITED STATES

Go

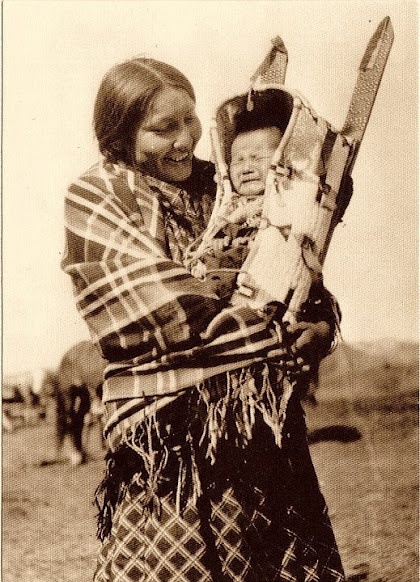

Native Americans in the United StatesNative Americans (also called American Indians, First Americans, or Indigenous Americans) are the Indigenous peoples of the United States, particularly of the lower 48 states and Alaska. They may also include any Americans whose origins lie in any of the indigenous peoples of North or South America. The United States Census Bureau publishes data about "American Indians and Alaska Natives", whom it defines as anyone "having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America ... and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment". The census does not, however, enumerate "Native Americans" as such, noting that the latter term can encompass a broader set of groups, e.g. Native Hawaiians, which it tabulates separately. The European colonization of the Americas from 1492 resulted in a precipitous decline in the size of the Native American population because of newly introduced diseases, including weaponized diseases and biological warfare by colonizers, wars, ethnic cleansing, and enslavement. Numerous scholars have classified elements of the colonization process as comprising genocide against Native Americans. As part of a policy of settler colonialism, European settlers continued to wage war and perpetrated massacres against Native American peoples, removed them from their ancestral lands, and subjected them to one-sided government treaties and discriminatory government policies. Into the 20th century, these policies focused on forced assimilation. When the United States was established, Native American tribes were considered semi-independent nations, because they generally lived in communities which were separate from communities of white settlers. The federal government signed treaties at a government-to-government level until the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871 ended recognition of independent Native nations, and started treating them as "domestic dependent nations" subject to applicable federal laws. This law did preserve rights and privileges, including a large degree of tribal sovereignty. For this reason, many Native American reservations are still independent of state law and the actions of tribal citizens on these reservations are subject only to tribal courts and federal law. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted US citizenship to all Native Americans born in the US who had not yet obtained it. This emptied the "Indians not taxed" category established by the United States Constitution, allowed Natives to vote in elections, and extended the Fourteenth Amendment protections granted to people "subject to the jurisdiction" of the United States. However, some states continued to deny Native Americans voting rights for decades. Titles II through VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 comprise the Indian Civil Rights Act, which applies to Native American tribes and makes many but not all of the guarantees of the U.S. Bill of Rights applicable within the tribes. Since the 1960s, Native American self-determination movements have resulted in positive changes to the lives of many Native Americans, though there are still many contemporary issues faced by them. Today, there are over five million Native Americans in the US, about 80% of whom live outside reservations. As of 2020, the states with the highest percentage of Native Americans are Alaska, Oklahoma, Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas.

List of Native Americans of the United StatesThis list of Native Americans is of notable individuals who are Native Americans in the United States, including Alaska Natives and American Indians. Native American identity is a complex and contested issue. The Bureau of Indian Affairs defines Native American as being American Indian or Alaska Native. Legally, being Native American is defined as being enrolled in a federally recognized tribe including Alaska Native villages. Ethnologically, factors such as culture, history, language, religion, and familial kinships can influence Native American identity. All individuals on this list should have Native American ancestry. Historical figures might predate tribal enrollment practices and would be included based on ethnological tribal membership.

History of Native Americans in the United StatesThe history of Native Americans in the United States began tens of thousands of years ago with the settlement of the Americas by the Paleo-Indians. The Eurasian migration to the Americas occurred over millennia via Beringia, a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska, as early humans spread southward and eastward, forming distinct cultures. Archaeological evidence suggests these migrations began 20,000 years ago and continued until around 12,000 years ago, with the earliest inhabitants classified as Paleo-Indians, who spread throughout the Americas, diversifying into numerous culturally distinct nations. Major Paleo-Indian cultures included the Clovis and Folsom traditions, identified through unique spear points and large-game hunting methods, especially during the Lithic stage. Around 8000 BCE, as the climate stabilized, new cultural periods like the Archaic stage arose, during which hunter-gatherer communities developed complex societies across North America. The Mound Builders created large earthworks, such as at Watson Brake and Poverty Point, which date to 3500 BCE and 2200 BCE, respectively, indicating early social and organizational complexity. By 1000 BCE, Native societies in the Woodland period developed advanced social structures and trade networks, with the Hopewell tradition connecting the Eastern Woodlands to the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico. This period led to the Mississippian culture, with large urban centers like Cahokia—a city with complex mounds and a population exceeding 20,000 by 1250 CE. From the 15th century onward, European contact drastically reshaped the Americas. Explorers and settlers introduced diseases, causing massive Indigenous population declines, and engaged in violent conflicts with Native groups. By the 19th century, westward U.S. expansion, rationalized by Manifest destiny, pressured tribes into forced relocations like the Trail of Tears, which decimated communities and redefined Native territories. Despite resistance in events like the Sioux Uprising and Battle of Little Bighorn, Native American lands continued to be reduced through policies like the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and later the Dawes Act, which undermined communal landholding. In the 20th century, Native Americans served in significant numbers during World War II, marking a turning point for Indigenous visibility and involvement in broader American society. Post-war, Native activism grew, with movements such as the American Indian Movement (AIM) drawing attention to Indigenous rights. Landmark legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 recognized tribal autonomy, leading to the establishment of Native-run schools and economic initiatives. By the 21st century, Native Americans had achieved increased control over tribal lands and resources, although many communities continue to grapple with the legacy of displacement and economic challenges. Urban migration has also grown, with over 70% of Native Americans residing in cities by 2012, navigating issues of cultural preservation and discrimination. Continuing legal and social efforts address these concerns, building on centuries of resilience and adaptation that characterize Indigenous history across the Americas.

List of Native Americans in the United States CongressThis is a list of Native Americans with documented tribal ancestry or affiliation who are in the United States Congress. All entries on this list are related to Native American tribes based in the continental United States. There are Native Hawaiians who have served in Congress, but they are not listed here because they are distinct from North American Natives. Richard H. Cain was the first Native American to serve in Congress, serving in the United States House of Representatives. Charles Curtis was the first Native American to serve in the United States Senate and would go on to become the first Native American Vice President of the United States. Only two Native Americans served in the 115th Congress: Tom Cole (serving since 2003) and Markwayne Mullin (served from 2013 until 2023), both of whom are Republican Representatives from Oklahoma. On November 6, 2018, Democrats Sharice Davids of Kansas and Deb Haaland of New Mexico were elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, and the 116th Congress, which commenced on January 3, 2019, had four Native Americans. Davids and Haaland are the first two Native American women with documented tribal ancestry to serve in Congress. At the start of the 117th Congress on January 3, 2021, five Native Americans were serving in the House, the largest Native delegation in history: Cole, Mullin, Haaland and Davids were all reelected in 2020, with Republican Yvette Herrell of New Mexico elected for the first time in 2020. The number dropped back down to four on March 16, 2021 when Haaland resigned her House seat to become the first Native American Secretary of the Interior. On August 16, 2022, Mary Peltola, a Yup'ik woman, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives to represent Alaska, becoming the first person with documented Native Alaskan ancestry to serve in Congress. This returned the number of the Native delegation to five, with a partisan split of three Republicans and two Democrats. This also marked the first time that a Native American, Native Alaskan, and Native Hawaiian (Kai Kahele) simultaneously served in Congress. Following the November 2022 elections, incumbents Cole (R-OK), Davids (D-KS) and Peltola (D-AK) all retained their seats, while Cherokee Republican Markwayne Mullin retired from the House and was elected to the Senate: Mullin became the first Native senator since the retirement of Ben Nighthorse Campbell (R-CO) in 2005, and his House seat was won by Choctaw Republican Josh Brecheen. In the same election, Yvette Herrell lost her seat due to redistricting, which drew litigation over alleged political gerrymandering; as such, Native Americans in the 118th Congress remain five, four in the House and one in the Senate. The partisan split is three Republicans and two Democrats. The states represented by Native members of Congress also dropped from four to three with Herrell's defeat in New Mexico.

Native Americans in United States electionsNative Americans in the United States have had a unique history in their ability to vote and participate in United States elections and politics. Native Americans have been allowed to vote in United States elections since the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, but were historically barred in different states from doing so. After a long history of fighting against voting rights restrictions, Native Americans now play an increasingly integral part in United States elections. They have been included in more recent efforts by political campaigns to increase voter turnout. Such efforts have borne more notable fruit since the 2020 U.S. presidential election, when Native American turnout was attributed to the historic flipping of the state of Arizona, which had not voted for the Democratic Party since the 1996 U.S. presidential election. Despite this increase, in general, voter turnout remains low among Native Americans, as does overall trust in American political institutions. They are usually more likely to vote in tribal elections and to trust their officials.

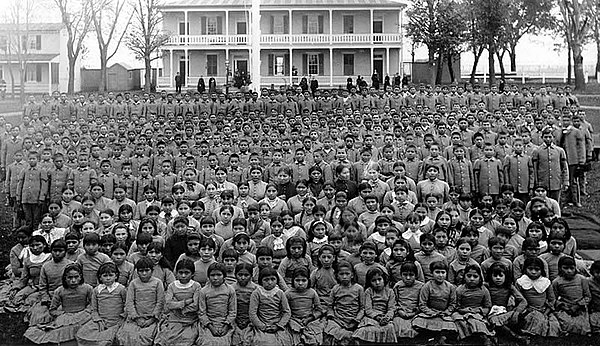

Racism against Native Americans in the United StatesBoth during and after the colonial era in American history, white settlers engaged in prolonged conflicts with Native Americans in the United States, seeking to displace them and seize their lands, resulting in American enslavement and forced assimilation into settler culture. The 19th century witnessed a surge in efforts to forcibly remove certain Native American nations, while those who remained faced systemic racism at the hands of the federal government. Ideologies like Manifest destiny justified the violent expansion westward, leading to the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and armed clashes. The dehumanization and demonization of Native Americans, epitomized in the United States Declaration of Independence, underscored a pervasive attitude that underpinned colonial and post-colonial policies. Historical events such as the California genocide, American Indian Wars, and the forced removal of the Navajos reflected the deep-seated racism and violence which were both ingrained in American expansionism, perpetuating a legacy of suffering, forced displacement, and death among indigenous peoples. Today, despite legal recognition of their formal equality, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders grapple with economic disparities and disproportionately high rates of health issues, including alcoholism, depression, and suicide. Native Americans face a higher likelihood of being killed in police encounters than any other racial or ethnic group. Native Americans are underrepresented and receive harsher sentences in the criminal justice system, and experience severe disparities in health and healthcare. Racism, oppression, and discrimination persist, fueling a crisis of violence against Native Americans, compounded by societal indifference.

Native American genocide in the United StatesThe destruction of Native American peoples, cultures, and languages has been characterized as genocide. Debates are ongoing as to whether the entire process or only specific periods or events meet the definitions of genocide. Many of these definitions focus on intent, while others focus on outcomes. Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term "genocide", considered the displacement of Native Americans by European settlers as a historical example of genocide. Others, like historian Gary Anderson, contend that genocide does not accurately characterize any aspect of American history, suggesting instead that ethnic cleansing is a more appropriate term. Historians have long debated the pre-European population of the Americas. In 2023, historian Ned Blackhawk suggested that Northern America's population (Including modern-day Canada and the United States) had halved from 1492 to 1776 from about 8 million people (all Native American in 1492) to under 4 million (predominantly white in 1776). Russell Thornton estimated that by 1800, some 600,000 Native Americans lived in the regions that would become the modern United States and declined to an estimated 250,000 by 1890 before rebounding. The virgin soil thesis (VST), coined by historian Alfred W. Crosby, proposes that the population decline among Native Americans after 1492 is due to Native populations being immunologically unprepared for Old World diseases. While this theory received support in popular imagination and academia for years, recently, scholars such as historians Tai S. Edwards and Paul Kelton argue that Native Americans "'died because U.S. colonization, removal policies, reservation confinement, and assimilation programs severely and continuously undermined physical and spiritual health. Disease was the secondary killer.'" According to these scholars, certain Native populations did not necessarily plummet after initial contact with Europeans, but only after violent interactions with colonizers, and at times such violence and colonial removal exacerbated disease's effects. The population decline among Native Americans after 1492 is attributed to various factors, mostly Eurasian diseases like influenza, pneumonic plagues, cholera, and smallpox. Additionally, conflicts, massacres, forced removal, enslavement, imprisonment, and warfare with European settlers contributed to the reduction in populations and the disruption of traditional societies. Historian Jeffrey Ostler emphasizes the importance of considering the American Indian Wars, campaigns by the U.S. Army to subdue Native American nations in the American West starting in the 1860s, as genocide. Scholars increasingly refer to these events as massacres or "genocidal massacres", defined as the annihilation of a portion of a larger group, sometimes intended to send a message to the larger group. Native American peoples have been subject to both historical and contemporary massacres and acts of cultural genocide as their traditional ways of life were threatened by settlers. Colonial massacres and acts of ethnic cleansing explicitly sought to reduce Native populations and confine them to reservations. Cultural genocide was also deployed, in the form of displacement and appropriation of Indigenous knowledge, to weaken Native sovereignty. Native American peoples still face challenges stemming from colonialism, including settler occupation of their traditional homelands, police brutality, hate crimes, vulnerability to climate change, and mental health issues. Despite this, Native American resistance to colonialism and genocide has persisted both in the past and the present.

Quick Access

Tag Explorer

Discover Fresh Ideas in the Universe of aéPiot

MultiSearch | Search | Tag Explorer

SHEET MUSIC | DIGITAL DOWNLOADS