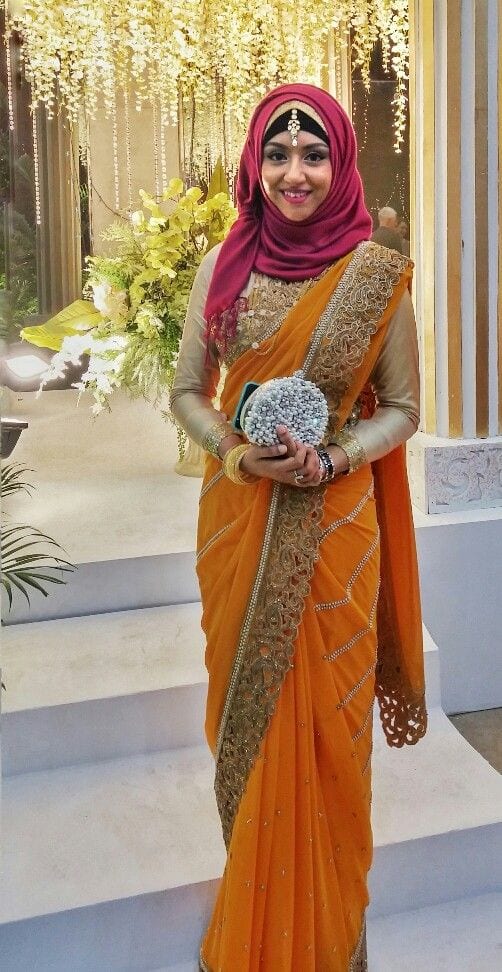

Muslim Style

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

Мусульманский интернет-магазин «Muslim-style» предлагает огромный выбор исламской одежды, соответствующую всем требованиям шариата по низким ценам в Москве и по всей России

"Muslim Style" - является официальным представителем производителей мусульманской одежды. Доставка осуществляется по всему миру.

https://www.marieclaire.com/fashion/news/g3060/muslim-women-style-fashion

Перевести · 11.08.2015 · There is no singular look when it comes to Muslim women's style—despite what the Western world may think. Some women of the faith cover their …

https://www.learnreligions.com/islamic-clothing-glossary-2004255

Перевести · 03.07.2019 · A long robe worn by Muslim men. The top is usually tailored like a shirt, but it is ankle-length and loose. The thobe is usually white but may be found in …

Muslim style chicken biriyani with chicken gravy

CHICKEN CURRY IN MUSLIM STYLE | NHANNI'S KITCHEN |

Хочешь получить настоящий эксклюзив? Уникальная одежда для уникальных людей, выделитесь и покажите всем свою любовь к …

Перевести · Great selection of Women Muslim Clothes & Style at affordable prices! Free shipping. 45 days money back guarantee. Friendly customer service.

https://my.mail.ru/mail/adic-87/video/156/162.html

01.03.2010 · MUSLIM STYLE – просмотров, продолжительность: 02:31 мин. Смотреть …

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_architecture

Some characteristics of Islamic architecture were inherited from pre-Islamic architecture of that region while some characteristics like minarets, muqarnas, arabesque, Islamic geometric pattern, pointed arch, multifoil arch, onion dome and pointed dome developed later.

Paradise garden

Gardens and water have for many centuries played an essential role in Islamic culture, an…

Some characteristics of Islamic architecture were inherited from pre-Islamic architecture of that region while some characteristics like minarets, muqarnas, arabesque, Islamic geometric pattern, pointed arch, multifoil arch, onion dome and pointed dome developed later.

Paradise garden

Gardens and water have for many centuries played an essential role in Islamic culture, and are often compared to the garden of Paradise. The comparison originates from the Achaemenid Empire. In his dialogue "Oeconomicus", Xenophon has Socrates relate the story of the Spartan general Lysander's visit to the Persian prince Cyrus the Younger, who shows the Greek his "Paradise at Sardis". The classical form of the Persian Paradise garden, or the Charbagh, comprises a rectangular irrigated space with elevated pathways, which divide the garden into four sections of equal size:

One of the hallmarks of Persian gardens is the four-part garden laid out with axial paths that intersect at the garden's centre. This highly structured geometrical scheme, called the chahar bagh, became a powerful metaphor for the organization and domestication of the landscape, itself a symbol of political territory.

A Charbagh from Achaemenid time has been identified in the archaeological excavations at Pasargadae. The gardens of Chehel Sotoun (Isfahan), Fin Garden (Kashan), Eram Garden (Shiraz), Shazdeh Garden (Mahan), Dowlatabad Garden (Yazd), Abbasabad Garden(Abbasabad), Akbarieh Garden (South Khorasan Province), Pahlevanpour Garden, all in Iran, form part of the UNESCO World Heritage. Large Paradise gardens are also found at the Taj Mahal (Agra), and at Humayun's Tomb (New Delhi), in India; the Shalimar Gardens (Lahore, Pakistan) or at the Alhambra and Generalife in Granada, Spain.

Courtyard (Sahn)

In the architecture of the Muslim world courtyards are found in secular and religious structures.

1. Residences and other secular buildings typically contain a central private courtyard or walled garden. This was also called the wast ad-dar ("middle of the house") in Arabic. The tradition of courtyard houses was already widespread in the ancient Mediterranean world and Middle East, as seen in Greco-Roman houses (e.g. the Roman domus). The use of this space included the aesthetic effects of plants and water, the penetration of natural light, allowing breezes and air circulation into the structure during summer heat, as a cooler space with water and shade, and as a protected and proscribed place where the women of the house need not be covered in the hijab clothing traditionally necessary in public.

2. A ṣaḥn (Arabic: صحن) – is the formal courtyard found in almost every mosque in Islamic architecture. The courtyards are open to the sky and surrounded on all sides by structures with halls and rooms, and often a shaded semi-open arcade. Sahns usually feature a centrally positioned ritual cleansing pool under an open domed pavilion called a howz. A mosque courtyard is used for performing ablutions and as a patio for rest or gathering.

Hypostyle hall

A hypostyle, i.e., an open hall supported by columns, is considered to be derived from architectural traditions of Achaemenid period Persian assembly halls (apadana). This type of building originated from the Roman-style basilica with an adjacent courtyard surrounded by colonnades, like Trajan's Forum in Rome. The Roman type of building has developed out of the Greek agora. In Islamic architecture, the hypostyle hall is the main feature of the hypostyle mosque. One of the earliest hypostyle mosques is the Tarikhaneh Mosque in Iran, dating back to the eighth century.

Vaulting

In Islamic buildings, vaulting follows two distinct architectural styles: While Umayyad architecture continues Syrian traditions of the sixth and seventh century, Eastern Islamic architecture was mainly influenced by Sasanian styles and forms.

Umayyad diaphragm arches and barrel vaults

In their vaulting structures, Umayyad period buildings show a mixture of ancient Roman and Persian architectural traditions. Diaphragm arches with lintelled ceilings made of wood or stone beams, or, alternatively, with barrel vaults, were known in the Levant since the classical and Nabatean period. They were mainly used to cover houses and cisterns. The architectural form of covering diaphragm arches with barrel vaults, however, was likely newly introduced from Iranian architecture, as similar vaulting was not known in Bilad al-Sham before the arrival of the Umayyads. However, this form was well known in Iran from early Parthian times, as exemplified in the Parthian buildings of Aššur. The earliest known example for barrel vaults resting on diaphragm arches from Umayyad architecture is known from Qasr Harane in Syria. During the early period, the diaphragm arches are built from coarsely cut limestone slabs, without using supporting falsework, which were connected by gypsum mortar. Later-period vaults were erected using pre-formed lateral ribs modelled from gypsum, which served as a temporal formwork to guide and center the vault. These ribs, which were left in the structure afterwards, do not carry any load. The ribs were cast in advance on strips of cloth, the impression of which can still be seen in the ribs today. Similar structures are known from Sasanian architecture, for example from the palace of Firuzabad. Umayyad-period vaults of this type were found in Amman Citadel and in Qasr Amra.

Spain (al-Andalus)

The double-arched system of arcades of the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba is generally considered to be derived from Roman aqueducts like the nearby aqueduct of Los Milagros. Columns are connected by horseshoe arches, and support pillars of brickwork, which are in turn interconnected by semicircular arches supporting the flat timberwork ceiling.

• Arcades of the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba

• Arcades of the Aljafería of Zaragoza

In later-period additions to the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba, the basic architectural design was changed: horseshoe arches were now used for the upper row of arcades, which were now supported by five-pass arches. In sections which now supported domes, additional supporting structures were needed to bear the thrust of the cupolas. The architects solved this problem by the construction of intersecting three- or five-pass arches. The three domes spanning the vaults above the mihrab wall are constructed as ribbed vaults. Rather than meeting in the centre of the dome, the ribs intersect one another off-center, forming an eight-pointed star in the centre, which is superseded by a pendentive dome.

The ribbed vaults of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba served as models for later mosque buildings in the Islamic West of al-Andalus and the Maghreb. At around 1000 AD, the Mezquita de Bab al Mardum (today Mosque of Cristo de la Luz) in Toledo was constructed with a similar, eight-ribbed dome. Similar domes are also seen in the mosque building of the Aljafería of Zaragoza. The architectural form of the ribbed dome was further developed in the Maghreb: the central dome of the Great Mosque of Tlemcen, a masterpiece of the Almoravids built in 1082, has twelve slender ribs, the shell between the ribs is filled with filigree stucco work.

Iran (Persia)

Because of its long history of building and re-building, spanning the time from the Abbasids to the Qajar dynasty, and its excellent state of conservation, the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan provides an overview over the experiments Islamic architects conducted with complicated vaulting structures.

The system of squinches, which is a construction filling in the upper angles of a square room so as to form a base to receive an octagonal or spherical dome, was already known in Sasanian architecture. The spherical triangles of the squinches were split up into further subdivisions or systems of niches, resulting in a complex interplay of supporting structures forming an ornamental spatial pattern which hides the weight of the structure.

The "non-radial rib vault", an architectural form of ribbed vaults with a superimposed spherical dome, is the characteristic architectural vault form of the Islamic East. From its beginnings in the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, this form of vault was used in a sequence of important buildings up to the period of Safavid architecture. Its main characteristics are:

1. four intersecting ribs, at times redoubled and intersected to form an eight-pointed star;

2. the omission of a transition zone between the vault and the supporting structure;

3. a central dome or roof lantern on top of the ribbed vault.

While intersecting pairs of ribs from the main decorative feature of Seljuk architecture, the ribs were hidden behind additional architectural elements in later periods, as exemplified in the dome of the Tomb of Ahmed Sanjar in Merv, until they finally disappeared completely behind the double shell of a stucco dome, as seen in the dome of Ālī Qāpū in Isfahan.

• Dome of the Fire temple of Harpak in Abyaneh

• Non-radial rib vault in the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan

• Dome of the tomb of Ahmed Sanjar in Merv

• Upper dome of Ālī Qāpū, Isfahan

• Adina Mosque, West Bengal, India

Domes

Based on the model of pre-existing Byzantine domes, the Ottoman architecture developed a specific form of monumental, representative building: wide central domes with huge diameters were erected on top of a centre-plan building. Despite their enormous weight, the domes appear virtually weightless. Some of the most elaborate domed buildings have been constructed by the Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan.

When the Ottomans had conquered Constantinople, they found a variety of Byzantine Christian churches, the largest and most prominent amongst them was the Hagia Sophia. The brickwork-and-mortar ribs and the spherical shell of the central dome of the Hagia Sophia were built simultaneously, as a self-supporting structure without any wooden centring. In the early Byzantine church of Hagia Irene, the ribs of the dome vault are fully integrated into the shell, similar to Western Roman domes, and thus are not visible from within the building. In the dome of the Hagia Sophia, the ribs and shell of the dome unite in a central medallion at the apex of the dome, the upper ends of the ribs being integrated into the shell; shell and ribs form one single structural entity. In later Byzantine buildings, like the Kalenderhane Mosque, the Eski Imaret Mosque (formerly the Monastery of Christ Pantepoptes) or the Pantokrator Monastery (today Zeyrek Mosque), the central medallion of the apex and the ribs of the dome became separate structural elements: the ribs are more pronounced and connect to the central medallion, which also stands out more pronouncedly, so that the entire construction gives the impression as if ribs and medallion are separate from, and underpin, the proper shell of the dome. Elaborately decorated ceilings and dome interiors draw influence from Near Eastern and Mediterranean architectural decoration while also serving as explicit and symbolic representations of the heavens. These dome shaped architectural features could be seen at the early Islamic palaces such as Qusayr ῾amra (c.712–15) and Khirbat al-mafjar (c.724–43).

Mimar Sinan solved the structural issues of the Hagia Sophia dome by constructing a system of centrally symmetric pillars with flanking semi-domes, as exemplified by the design of the Süleymaniye Mosque (four pillars with two flanking shield walls and two semi-domes, 1550–1557), the Rüstem Pasha Mosque (eight pillars with four diagonal semi-domes, 1561–1563), and the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne (eight pillars with four diagonal semi-domes, 1567/8–1574/5). In the history of architecture, the structure of the Selimiye Mosque has no precedent. All elements of the building subordinate to its great dome.

• Schematic drawing of a pendentive dome

• Central domes of the Hagia Sophia

• Dome of the Kalenderhane Mosque

• Selimiye Mosque, Edirne

• Sultan Ahmed Mosque

Muqarnas

The architectural element of muqarnas developed in northeastern Iran and the Maghreb around the middle of the 10th century. The ornament is created by the geometric subdivision of a vaulting structure into miniature, superimposed pointed-arch substructures, also known as "honeycomb", or "stalactite" vaults. Made from different materials like stone, brick, wood or stucco, its use in architecture spread over the entire Islamic world. In the Islamic West, muqarnas are also used to adorn the outside of a dome, cupola, or similar structure, while in the East is more limited to the interior face of a vault.

• Design of a muqarnas quarter vault from the Topkapı Scroll

• Muqarnas in the necropolis of Shah-i-Zinda, Samarqand

• Muqarnas in the Alhambra

• The muqarna of a mosque in Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Ornaments

As a common feature, Islamic architecture makes use of specific ornamental forms, including mathematically complicated, elaborate geometric patterns, floral motifs like the arabesque, and elaborate calligraphic inscriptions, which serve to decorate a building, specify the intention of the building by the selection of the textual program of the inscriptions. For example, the calligraphic inscriptions adorning the Dome of the Rock include quotations from the Quran (e.g., Quran 19:33–35) which reference the miracle of Jesus and his human nature.

The geometric or floral, interlaced forms, taken together, constitute an infinitely repeated pattern that extends beyond the visible material world. To many in the Islamic world, they symbolize the concept of infinite proves of existence of one eternal God. Furthermore, the Islamic artist conveys a definite spirituality without the iconography of Christian art. Non-figural ornaments are used in mosques and buildings around the Muslim world, and it is a way of decorating using beautiful, embellishing and repetitive Islamic art instead of using pictures of humans and animals (which some Muslims believe is forbidden (Haram) in Islam).

Instead of recalling something related to the reality of the spoken word, calligraphy for the Muslim is a visible expression of spiritual concepts. Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The holy book of Islam, al-Qur'ān, has played a vital role in the development of the Arabic language, and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. Proverbs and complete passages from the Qur'an are still active sources for Islamic calligraphy. Contemporary artists in the Islamic world draw on the heritage of calligraphy to use calligraphic inscriptions or abstractions in their work.

• Geometrical tile ornament (Zellij), Ben Youssef Madrasa, Maroc

• Calligraphic inscription on the dome of the Mevlana mausoleum

• Dome of the Shah Mosque in Isfahan with calligraphic inscription

• Bengali Islamic terracotta on a 17th-century mosque in Tangail, Bangladesh

• Tiles in Topkapı Palace, an example of Ottoman Architecture

• Divriği Great Mosque and Hospital, an example of Seljuk architecture in Turkey

Architectural forms

Many forms of Islamic architecture have evolved in different regions of the Islamic world. Notable Islamic architectural types include the early Abbasid buildings, T-Type mosques, and the central-dome mosques of Anatolia. The oil-wealth of the 20th century drove a great deal of mosque construction using designs from leading modern architects.

Arab-plan or hypostyle mosques are the earliest type of mosques, pioneered under the Umayyad Dynasty. These mosques are square or rectangular in plan with an enclosed courtyard and a covered prayer hall. Historically, because of the warm Mediterranean and Middle Eastern climates, the courtyard served to accommodate the large number of worshippers during Friday prayers. Most early hypostyle mosques have flat roofs on top of prayer halls, necessitating the use of numerous columns and supports. One of the most notable hypostyle mosques is the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba, Spain, as the building is supported by over 850 columns. Frequently, hypostyle mosques have outer arcades so that visitors can enjoy some shade. Arab-plan mosques were constructed mostly under the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties; subsequently, however, the simplicity of the Arab plan limited the opportunities for further development, and as a result, these mosques gradually fell out of popularity.

The Ottomans introduced domed mosques in the 15th century with a large dome centered over the prayer hall. In larger mosques, smaller domes are often built off-center throughout the rest of the complex, where prayers are not performed - exemplified by Istanbul's Blue Mosque. This style was heavily influenced by the Byzantine church architecture with its use of large central domes.

• Prayer Hall of the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba, Spain

• A sample of modern Islamic architecture - The mosque of international conferences center in Isfahan, Iran

• Sancaklar Mosque, A modern mosque in Istanbul

Specific architectural elements

Islamic architecture may be identified with the following design elements, which were inherited from the first mosque buildings (originally a feature of the Masjid al-

Real Mother Son Submission Who Fuck

Long Cock Xxx

Skachat Hijab Mother Porno Skachat

Xxx Brazzers Mother

Tableofcontents Latex

Muslim-style

MS | Muslim Style | ВКонтакте - VK

Muslim Women Fashion and Style - Muslim Fashionistas

The 11 Most Common Types of Islamic Clothing

Одежда Muslim-Style.ru | ВКонтакте

Buy Women Muslim Clothes & Style online

Islamic architecture - Wikipedia

Muslim & Style – Muslim & Style

Muslim Style