Muslim Ban

🛑 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 INFORMATION AVAILABLE CLICK HERE👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

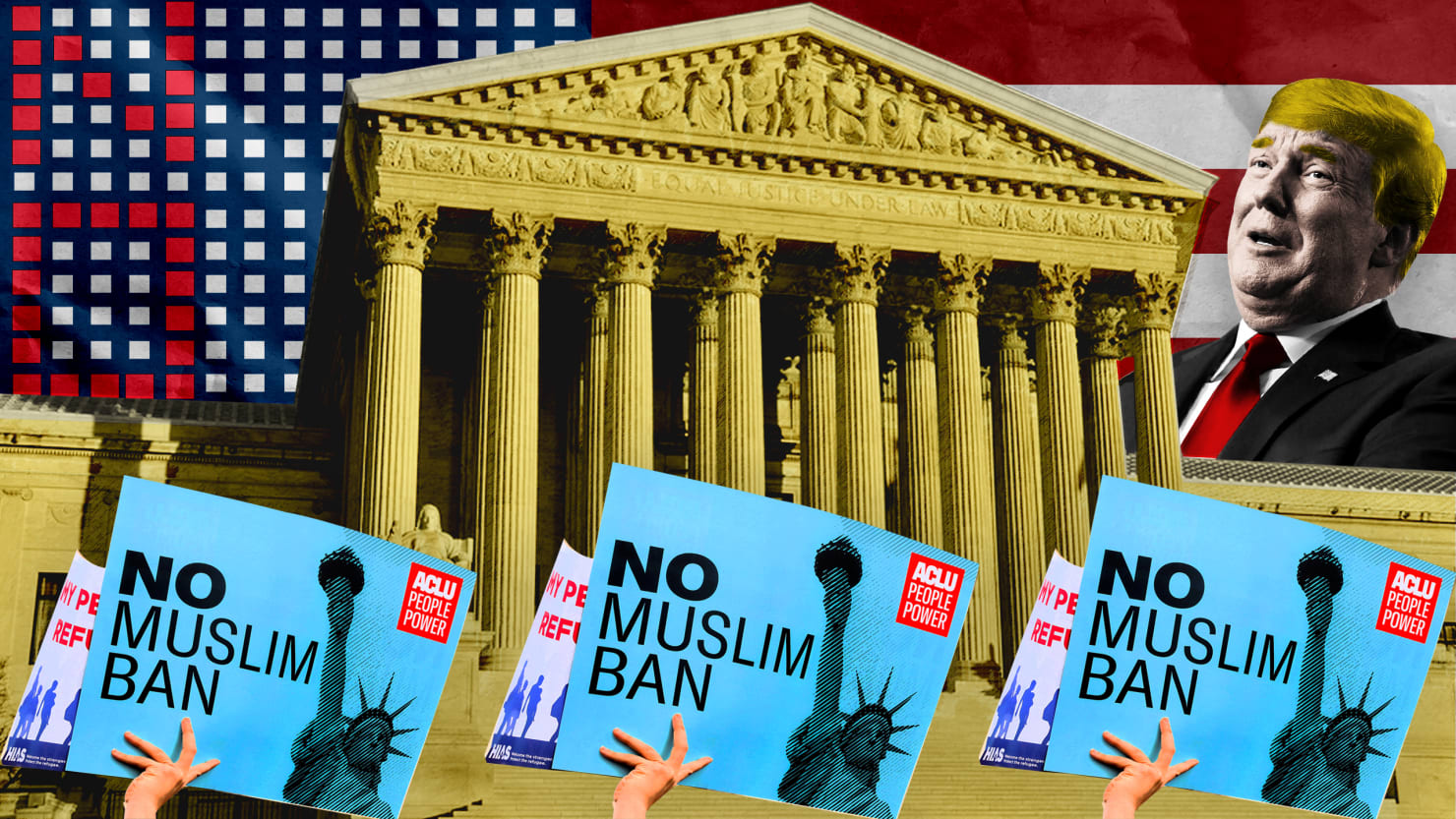

Executive Order 13769, titled Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States, otherwise known as the Muslim Ban[1] or a travel ban, was a controversial executive order by former US President Donald Trump. Except for the extent to which it was blocked by various courts, it was in effect from January 27, 2017, until March 6, 2017, when it was superseded by Executive Order 13780. Executive Order 13769 lowered the number of refugees to be admitted into the United States in 2017 to 50,000, suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) for 120 days, suspended the entry of Syrian refugees indefinitely, directed some cabinet secretaries to suspend entry of those whose countries do not meet adjudication standards under U.S. immigration law for 90 days, and included exceptions on a case-by-case basis. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) listed these countries as Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen.[2] More than 700 travelers were detained, and up to 60,000 visas were "provisionally revoked".[3]

Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States

U.S. President Donald Trump signing the order at the Pentagon, with Vice President Mike Pence (left) and Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis

Executive Order 13769 in the Federal Register

Suspends the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program for 120 days*

Restricts admission of citizens from seven countries for 90 days*

Orders list of countries for entry restrictions after 90 days

Suspends admission of Syrian refugees indefinitely

Prioritizes refugee claims by individuals from minority religions on the basis of religious-based persecution

Expedites a biometric tracking system

Other provisions

* Not in force since 3 February 2017

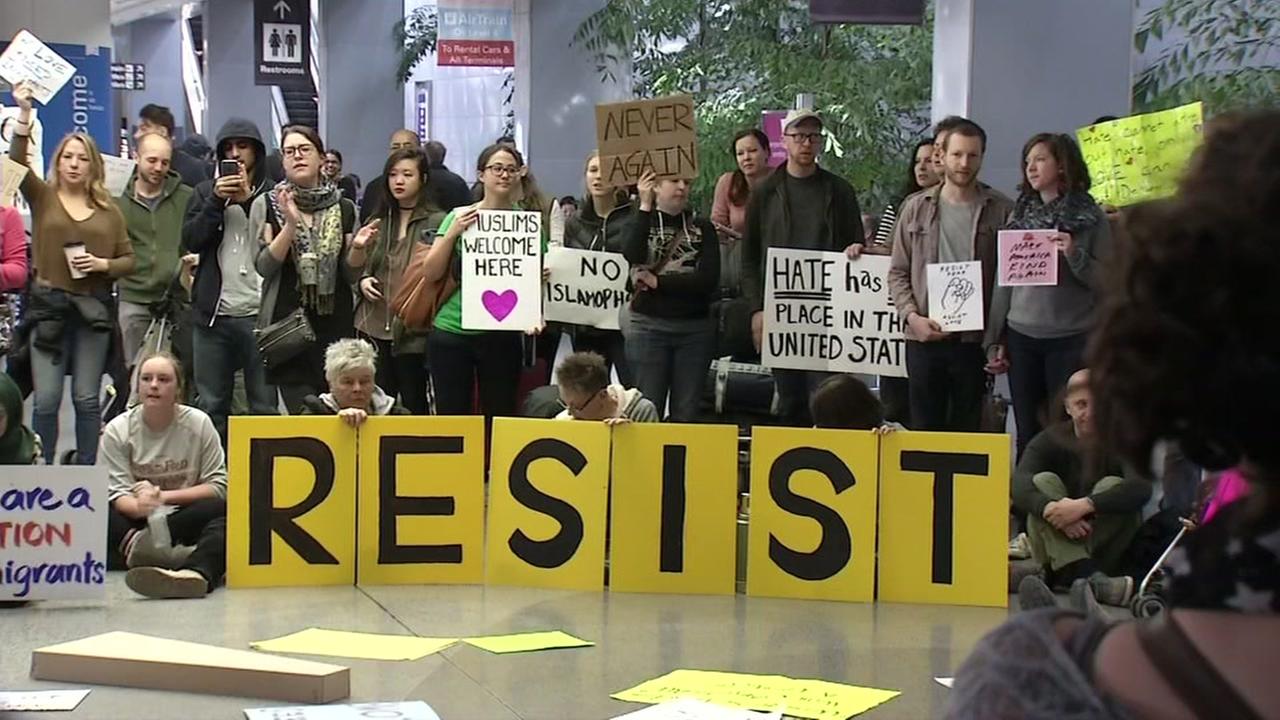

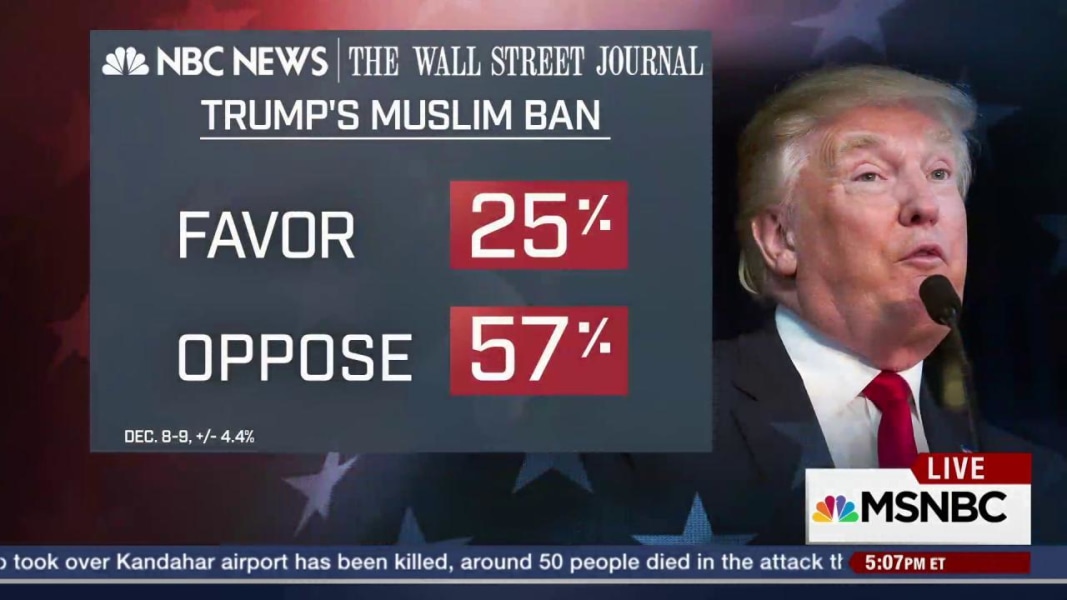

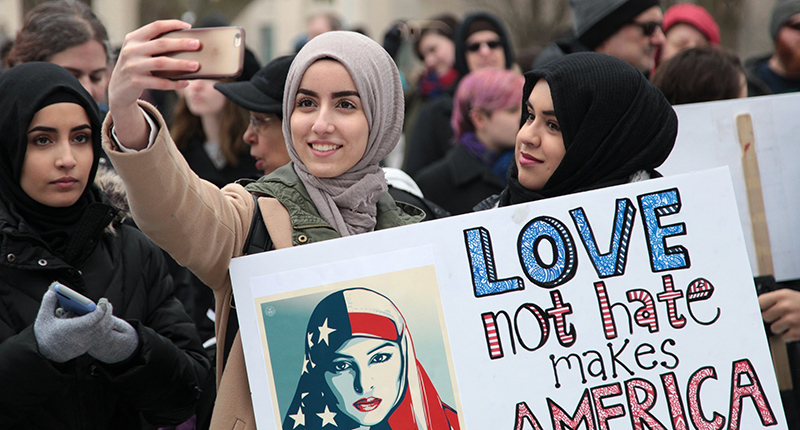

The signing of the Executive Order provoked widespread condemnation and protests and resulted in legal intervention against the enforcement of the order with some calling it a "Muslim ban" because President Trump had previously called for temporarily banning Muslims from entering America soon after the 2015 San Bernardino terrorist attack (a call he reiterated after the Orlando nightclub shooting six months later[citation needed]), and because all of the affected countries had a Muslim majority.[1] A nationwide temporary restraining order (TRO) was issued on February 3, 2017 in the case Washington v. Trump, which was upheld by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit on February 9, 2017. Consequently, the Department of Homeland Security stopped enforcing portions of the order and the State Department re-validated visas that had been previously revoked. Later, other orders (Executive Order 13780 and Presidential Proclamation 9645) were signed by President Trump and superseded Executive Order 13769. On June 26, 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the third Executive Order (Presidential Proclamation 9645) and its accompanying travel ban in a 5–4 decision, with the majority opinion being written by Chief Justice John Roberts.[4]

On January 20, 2021, President Joe Biden revoked Executive Order 13780 and its related proclamations with Presidential Proclamation 10141.[5]

Key provisions of executive orders 13769 and 13780 cite to paragraph (f) of Title 8 of the United States Code § 1182, which discusses inadmissible aliens. Paragraph (f) states:

Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.[a]

No person shall receive any preference or priority or be discriminated against in the issuance of an immigrant visa because of the person's race, sex, nationality, place of birth, or place of residence.[b]

The language in the INA of 1965 is among the reasons District of Maryland Judge Chuang issued a temporary restraining order blocking Section 2(c) of Executive Order 13780.[7]

In 1986, the Visa Waiver Program was initiated by President Ronald Reagan, allowing alien nationals of select countries to travel to the United States for up to 90 days without a visa, in return for reciprocal treatment of U.S. nationals. By 2016, the program had been extended to 38 countries.[8] In 2015, Congress passed a Consolidated Appropriations Act to fund the government, and Obama signed the bill into law. The Visa Waiver Program Improvement and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act of 2015, which was previously passed by the House of Representatives as H.R. 158, was incorporated into the Consolidated Appropriations Act as Division O, Title II, Section 203. The Trump administration's executive order relied on H.R. 158, as enacted.[9] The Visa Waiver Program Improvement and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act originally affected four countries: Iraq, Syria, and countries on the State Sponsors of Terrorism list (Iran and Sudan). Foreigners who were nationals of those countries, or who had visited those countries since 2011, were required to obtain a visa to enter the United States, even if they were nationals or dual-nationals of the 38 countries participating in the Visa Waiver Program.[10] Libya, Yemen, and Somalia were added later as "countries of concern" by Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson during the Obama administration.[11][12][13][14][15][16] The executive order refers to these countries as "countries designated pursuant to Division O, Title II, Section 203 of the 2016 consolidated Appropriations Act".[17] Prior to this, in 2011, additional background checks were imposed on the nationals of Iraq.[18]

Trump's press secretary Sean Spicer cited these existing restrictions as evidence that the executive order was based on outstanding policies saying that the seven targeted countries were "put (...) first and foremost" by the Obama administration.[15] Fact-checkers at PolitiFact.com, The New York Times, and The Washington Post said the Obama restrictions cannot be compared to this executive order because they were in response to a credible threat and were not a blanket ban on all individuals from those countries, and concluded that the Trump administration's statements about the Obama administration were misleading and false.[17][19][20]

Donald Trump became the U.S. president on January 20, 2017. He has long claimed that terrorists are using the U.S. refugee resettlement program to enter the country.[22] As a candidate Trump's "Contract with the American Voter" pledged to suspend immigration from "terror-prone regions".[23][24] Trump-administration officials then described the executive order as fulfilling this campaign promise.[25] Speaking of Trump's agenda as implemented through executive orders and the judicial appointment process, White House chief strategist Steve Bannon stated: "If you want to see the Trump agenda it's very simple. It was all in the [campaign] speeches. He's laid out an agenda with those speeches, with the promises he made, and [my and Reince Priebus'] job every day is to just to execute on that. He's maniacally focused on that."[26][27]

During his initial election campaign Trump had proposed a temporary, conditional, and "total and complete" ban on Muslims entering the United States.[22][28][29][30] His proposal was met by opposition by U.S. politicians including Mike Pence and James Mattis.[28][31]

On June 12, in reference to the Orlando nightclub shooting that occurred on the same date, Trump used Twitter to renew his call for a Muslim immigration ban.[32][33] On June 13 Trump proposed to suspend immigration from "areas of the world" with a history of terrorism, a change from his previous proposal to suspend Muslim immigration to the U.S; the campaign did not announce the details of the plan at the time, but Jeff Sessions, an advisor to Trump campaign on immigration,[34] said the proposal was a statement of purpose to be supplied with details in subsequent months.[35]

On July 15, Pence, who as governor of Indiana attempted to suspend settlement of Syrian refugees to the state but was prevented from doing so by the courts, said that decision was based on the fall 2015 FBI assessment that there is risk associated with bringing in refugees. Pence cited the infiltration of Iraqi refugees in Bowling Green Kentucky who were arrested in 2011 for attempting to provide weapons to ISIS and Obama's suspension of the Iraqi refugee program in response as precedent for a U.S. President's "temporarily suspend[ing] immigration from countries where terrorist influence and impact represents a threat to the United States".[36][37]

On July 17, Trump (with Pence) participated in an interview on 60 Minutes that sought to clarify whether Trump's position on a Muslim ban had changed; when asked whether he had changed position on the Muslim ban, he said: "—no, I—Call it whatever you want. We'll call it territories, OK?"[38] Trump's response would later be interpreted by Judge Brinkema of the Eastern District of Virginia as acknowledging "the conceptual link between a Muslim ban and the [executive order]" in her ruling finding the executive order likely violates the Establishment Clause of the U.S. Constitution.[39][40]

In a speech on August 4 to a Maine audience Trump called for stopping the practice of admitting refugees from among the most dangerous places in the world; Trump specifically opposed Somali immigration to Minnesota and Maine, describing the Somali refugee program, which has resettled tens of thousands of refugees in the U.S., as creating "a rich pool of potential recruiting targets for Islamic terror groups". In Minnesota 10 men of Somali or Oromo family backgrounds were charged with conspiring to travel to the Middle East to join ISIS and 20 young men traveled to Somalia to join a terror group in 2007.[41][42] Trump went on to list alleged terrorist plots by immigrants from Somalia, Yemen, Iraq, and Syria, along with incidents of alleged terrorism plots or acts by immigrants from countries not among the seven specified by the eventual executive order such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, the Philippines, Uzbekistan, and Morocco.[42]

In a speech on August 15 Trump listed terrorism attacks in the United States (9/11; the 2009 Fort Hood shooting; the Boston Marathon bombing; the shootings in Chattanooga, Tennessee; and the Orlando nightclub shooting[43]) as justification for his proposals for increased ideological testing and a temporary ban on immigration from countries with a history of terrorism; on this point, the Los Angeles Times' analysis observed Trump "failed to mention that a number of the attackers were U.S. citizens, or had come to the U.S. as children".[44] (The same analysis also acknowledged an act of Congress eventually cited to in the executive order was probably what Trump would attempt to use in implementing such proposals.[44] No deaths in the U.S. had been caused by extremists with family backgrounds in any of the seven countries implicated by the executive order as of the day before it was signed.[45]) In the speech, Trump vowed to task the departments of State and Homeland Security to identify regions hostile to the United States such that the additional screening was justified to identify those who pose a threat.[46]

In a speech on August 31 Trump vowed to "suspend the issuance of visas" to "places like Syria and Libya".[47][48] On September 4 vice presidential candidate Mike Pence defended the Trump–Pence ticket's plan to suspend immigration from countries or regions of the world with a history of terrorism on Meet the Press. He gave Syria as an example of such a country or region: "Donald Trump and I believe that we should suspend the Syrian refugee program" because, Pence said, Syria was a region of the world that was "imploding into civil war" and had "been compromised by terrorism".[49]

In late November following the Ohio State attack, President-elect Trump claimed the attacker was a "Somali refugee who should not have been in" the U.S.[50] In early December he said the attack showed immigration security is national security when stating goals for his administration.[51][52] The attacker injured 11 before he was killed by police.[53] The attacker was a Somali-born refugee who spent seven years in Pakistan, the country from which he immigrated to the U.S. with his family on a refugee visa. The attacker was a legal permanent resident living in the U.S. reportedly inspired by but not in direct contact with ISIS.[50] In an interview given for a feature in the Ohio State student newspaper approximately two months before the attack, the eventual attacker expressed fear about Donald Trump's rhetoric toward Muslims and what it might mean for immigrants and refugees.[54]

In an interview broadcast the day he would sign the order President Trump told the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) that Christian refugees would be given priority in terms of refugee status in the United States[55][56] after saying that Syrian Christians were "horribly treated" by his predecessor, Barack Obama.[57][58] Christians make up very small fractions (0.1% to 1.5%) of the Syrian refugees who have registered with the UN High Commission for Refugees in Syria, Jordan, Iraq, and Lebanon; those registered represent the pool from which the U.S. selects refugees.[59]

António Guterres, then-UN high commissioner for refugees, said in October 2015 that many Syrian Christians have ties to the Christian community in Lebanon and have sought the UN's services in smaller numbers.[59] During 2016 the U.S. had admitted almost as many Christian as Muslim refugees. Pew research also pointed out that over 99% of admitted Syrian refugees were Muslim and less than 1% Christian, despite the demographics of Syria being estimated by Pew to be 93% Muslim and 5% Christian.[58] Senator Chris Coons (D-DE) accused Trump of spreading "false facts" and "alternative facts".[60]

In January 2016, the Department of Justice (DOJ), on request of the Senate Subcommittee on Immigration and the National Interest, provided a list of 580 public international terrorism and terrorism-related convictions from September 11, 2001 through the end of 2014.[61][62] Based on this data and news reports and other open-source information the committee in June determined that at least 380 among the 580 convicted were foreign-born.[63] The publicly released version of Trump's August 15 speech quoted that report.[64] Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato Institute said the list of 580 convictions shared by DOJ was problematic in that "241 of the 580 convictions (42 percent) were not even for terrorism offences"; they started with a terrorism tip but ended up with a non-terrorism charge like "receiving stolen cereal".[65][66][67][68] The day after Executive Order 13780 was signed, Ohio Congressman Bill Johnson said 60 individuals of the 380 foreign-born individuals or 580 total individuals (16% or 10%, respectively) were from the seven countries implicated by Executive Order 13769, but because Iraq is not among the six countries implicated in Executive Order 13780, Johnson suggested the number may be lower than 60 for countries implicated by that executive order.[69] Nowrasteh notes 40 of the 580 individuals (6.9%) were foreign-born immigrants or non-immigrants convicted of planning, attempting, or carrying out terrorist attacks on U.S. soil (his analysis does not specify whether any, some, or all 40 are from the six or seven countries specified by executive orders 13780 or 13769).[70] He contrasts this figure with EO 13780's statement that "[s]ince 2001, hundreds of persons born abroad have been convicted of terrorism-related crimes in the United States", which he says requires including planned acts outside the United States" because "If the people counted as 'terrorism-related' convictions were really convicted of planning, attempting, or carrying out a terrorist attack on U.S. soil then supporters of Trump's executive order would call them 'terrorism convictions' and exclude the [descriptor] 'related'."[70]

The New York Times said that candidate Trump in a speech on June 13, 2016, read from statutory language to justify the President's authority to suspend immigration from areas of the world with a history of terrorism.[35] The Washington Post identified the referenced statute as 8 U.S.C. 1182(f).[71] This was the statutory subsection eventually cited in sections 3, 5, and 6 of the executive order.[72]

According to CNN the executive order was developed primarily by White House officials (which the Los Angeles Times reported as including "major architect" Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon[73]) without input from the U.S. Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) that is typically a part of the drafting process. This was disputed by White House officials.[74] The OLC usually reviews all executive orders with respect to form and legality before issuance. The White House under previous administrations, including the Obama administration, has bypassed or overruled the OLC on sensitive matters of national security.[75]

Trump aides said that the order had been issued in consultation with Department of Homeland Security and State Department officials. Officials at the State Department and other agencies said it was not.[76][77] An official from the Trump administration said that parts of the order had been developed in the transition period between Trump's election and his inauguration.[78] CNN reported that Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly and Department of Homeland Security leadership saw the details shortly before the order was finalized.[79]

On January 31 John Kelly told reporters that he "did know it was under development" and had seen at least two drafts of the order.[80] (Note: With the final draft, two drafts of the order were public by the time the order was released on January 27. See prior leaked draft of order, which was public on January 25.) James Mattis, for the Department of Defense, did not see a final version of the order until the morning of the day President Trump signed it (the signing occurred shortly after Mattis' swearing-in ceremony for secretary of defense in the afternoon[81][82]) and the White House did not offer Mattis the chance to provide input while the order was drafted.[83] Rex Tillerson, though not yet confirmed as secretary of state, was involved in cabinet-level discussions about implementation of the order at least as early as 2:00 a.m. Sunday, January 29.[84] According to the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General, the only people at DHS who saw the executive order before it was signed were Kelly and DHS's acting general counsel, who was first shown the order one hour in advance of signing.[85][86] The DHS inspector general found that U.S. Cus

Www Mother Porn Com

Download Japan Mother And Son Xxx

Tits Massage Video

Mother Son Porno

Leather Men Porn

Executive Order 13769 - Wikipedia

What is the 'Muslim Ban'? - Anti-Defamation League

The Muslim Ban: What Just Happened? | American Civil ...

What is the Muslim Ban and how can we end it? | Oxfam

Trump travel ban - Wikipedia

Understanding Trump's Muslim Bans - National Immigration ...

Muslim Ban News | Today's latest from Al Jazeera

Muslim Ban

.jpg)