Muslim Art

💣 👉🏻👉🏻👉🏻 ALL INFORMATION CLICK HERE 👈🏻👈🏻👈🏻

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

^ Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, Richard Ettinghausen and Oleg Grabar , 2001, Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250 , Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-08869-4 , p.3; Brend, 10

^ J. M. Bloom; S. S. Blair (2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, Vol. II . New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1 .

^ Davies, Penelope J.E. Denny, Walter B. Hofrichter, Frima Fox. Jacobs, Joseph. Roberts, Ann M. Simon, David L. Janson's History of Art, Prentice Hall; 2007, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. Seventh Edition, ISBN 0-13-193455-4 pg. 277

^ MSN Encarta: Islamic Art and architecture . Archived from the original on 2009-10-28.

^ Melikian, Souren (December 5, 2008). "Qatar's Museum of Islamic Art: Despite flaws, a house of masterpieces" . International Herald Tribune . Retrieved September 6, 2011 . This is a European construct of the 19th century that gained wide acceptance following a display of Les Arts Musulmans at the old Trocadero palace in Paris during the 1889 Exposition Universelle. The idea of "Islamic art" has even less substance than the notion of "Christian art" from the British Isles to Germany to Russia during the 1000 years separating the reigns of Charlemagne and Queen Victoria might have.

^ Melikian, Souren (April 24, 2004). "Toward a clearer vision of 'Islamic' art" . International Herald Tribune . Retrieved September 6, 2011 .

^ Blair, Shirley S.; Bloom, Jonathan M. (2003). "The Mirage of Islamic Art: Reflections on the Study of an Unwieldy Field". The Art Bulletin . 85 (1): 152–184. doi : 10.2307/3177331 . JSTOR 3177331 .

^ De Guise, Lucien. "What is Islamic Art?". Islamica Magazine . Missing or empty |url= ( help )

^ Jump up to: a b Madden (1975), pp.423–430

^ Thompson, Muhammad; Begum, Nasima. "Islamic Textile Art: Anomalies in Kilims" . Salon du Tapis d'Orient . TurkoTek . Retrieved 25 August 2009 .

^ Alexenberg, Melvin L. (2006). The future of art in a digital age: from Hellenistic to Hebraic consciousness . Intellect Ltd. p. 55. ISBN 1-84150-136-0 .

^ Backhouse, Tim. "Only God is Perfect" . Islamic and Geometric Art . Retrieved 25 August 2009 .

^ Jump up to: a b Esposito, John L. (2011). What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15.

^ Jump up to: a b "Figural Representation in Islamic Art" . The Metropolitan Museum of Art .

^ Bondak, Marwa (2017-04-25). "Islamic Art History: An Influential Period" . Mozaico . Retrieved 26 May 2017 .

^ Islamic Archaeology in the Sudan - Page 22, Intisar Soghayroun Elzein - 2004

^ Arts, p. 223. see nos. 278–290

^ J. Bloom; S. Blair (2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art . New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. pp. 192 and 207. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1 .

^ Davies, Penelope J.E. Denny, Walter B. Hofrichter, Frima Fox. Jacobs, Joseph. Roberts, Ann M. Simon, David L. Janson's History of Art , Prentice Hall; 2007, Upper Saddle, New Jersey. Seventh Edition, ISBN 0-13-193455-4 pg. 298

^ King and Sylvester, throughout, but 9–28, 49–50, & 59 in particular

^ King and Sylvester, 27, 61–62, as "The Medici Mamluk Carpet"

^ King and Sylvester, 59–66, 79–83

^ King and Sylvester: Spanish carpets: 11–12, 50–52; Balkans: 77 and passim

^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Graves, Margaret (2 June 2009). "Columns in Islamic Architecture" . Retrieved 2018-11-26 .

^ Jump up to: a b c Graves, Margaret (2009). "Arches in Islamic Architecture". doi : 10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T2082057 . Cite journal requires |journal= ( help )

^ Mason (1995), p. 5

^ Henderson, J.; McLoughlin, S. D.; McPhail, D. S. (2004). "Radical changes in Islamic glass technology: evidence for conservatism and experimentation with new glass recipes from early and middle Islamic Raqqa, Syria". Archaeometry . 46 (3): 439–68. doi : 10.1111/j.1475-4754.2004.00167.x .

^ Mason (1995), p. 7

^ Arts, 206–207

^ See Rawson throughout; Canby, 120–123, and see index; Jones & Mitchell, 206–211

^ Savage, 175, suggests that the Persians had made some experiments towards producing it, and the earliest European porcelain, Medici porcelain , was made in the late 16th century, perhaps with a Persian or Levantine assistant on the team.

^ Baer, Eva (1983). Metalwork in Medieval Islamic Art . State University of New York Press . pp. 58, 86, 143, 151, 176, 201, 226, 243, 292, 304. ISBN 0-87395-602-8 .

^ Arts, 131, 135. The Introduction (pp. 131–135) is by Ralph Pinder-Wilson , who shared the catalogue entries with Waffiya Essy .

^ Encyclopaedia Judaica, "Glass", Online version

^ Arts, 131–133

^ Arts, 131, 141

^ Arts, 141

^ Endnote 111 in Roman glass: reflections on cultural change , Fleming, Stuart. see also endnote 110 for Jewish glassworkers

^ Arts, 131, 133–135

^ Arts, 131–135, 141–146; quote, 134

^ Arts, 134–135

^ Baer, Eva (1983). Metalwork in Medieval Islamic Art . SUNY Press. pp. whole book. ISBN 978-0-87395-602-4 .

^ Hadithic texts against gold and silver vessels

^ Arts, 201, and earlier pages for animal shapes.

^ But see Arts, 170, where the standard view is disputed

^ "Base of a ewer with Zodiac medallions [Iran] (91.1.530)" . Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, July 2011; see also on astrology , Carboni, Stefano. Following the Stars: Images of the Zodiac in Islamic Art. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997), 16. The inscription reads: "Bi-l-yumn wa al-baraka…" meaning "With bliss and divine grace…"

^ Arts, 157–160, and exhibits 161–204

^ See the relevant sections in "Arts"

^ Fatimid Rock Crystal Ewers, Most Valuable Objects in Islamic Art

^ Arts, 120–121

^ Table in the Victoria & Albert Museum

^ Rogers and Ward, 156

^ Arts, 147–150, and exhibits following

^ Arts, 65–68; 74, no. 3

^ Louvre, Suaire de St-Josse Archived 2011-06-23 at the Wayback Machine . Exhibited as no. 4 in Arts, 74.

^ Arts, 68, 71, 82–86, 106–108, 110–111, 114–115

^ Gruber, World of Art

^ Hillenbrand (1999), p.40

^ Hillenbrand (1999), p.54

^ Hillenbrand (1999), p.58

^ Hillenbrand (1999), p.89

^ Hillenbrand (1999), p.91

^ Hillenbrand (1999), Chapter 4

^ Hillenbrand, p.100

^ Hillenbrand, p.128-131

^ Levey, chapters 5 and 6

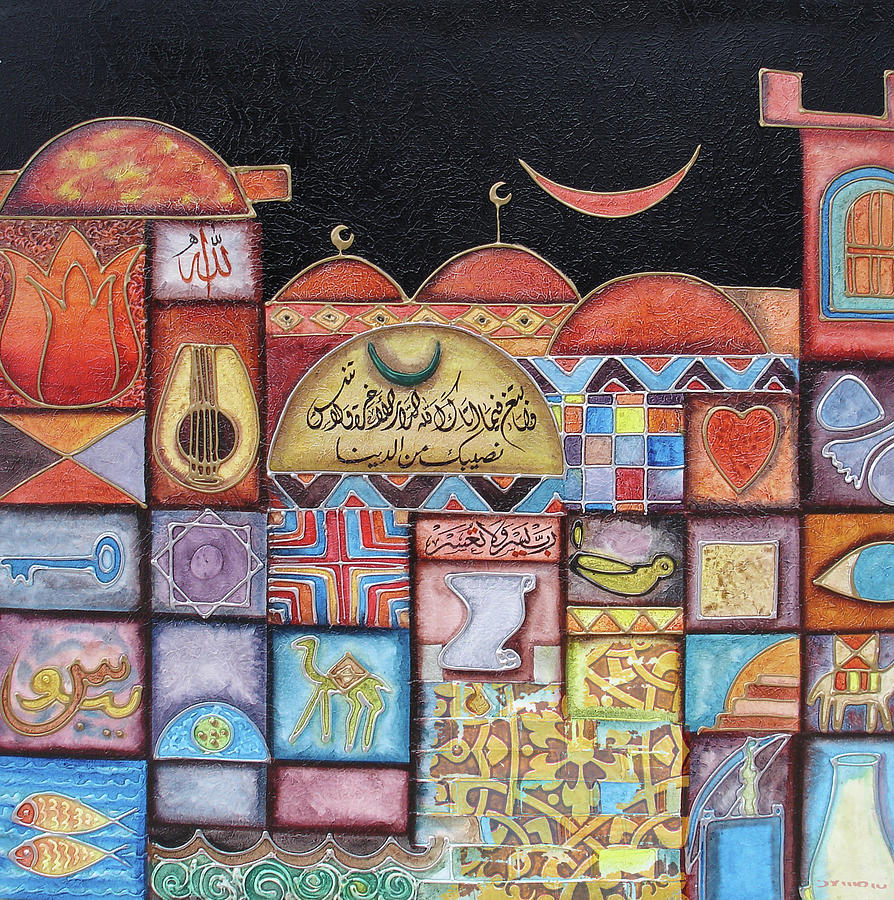

Islamic art encompasses the visual arts produced in the Islamic world . [1] Islamic art is difficult to characterize because it covers a wide range of lands, periods, and genres, [2] including Islamic architecture , Islamic calligraphy , Islamic miniature , Islamic glass , Islamic pottery , and textile arts such as carpets and embroidery . It comprises both religious and secular art forms. Religious art is represented by calligraphy, architecture and furnishings of religious buildings, such as mosque fittings (e.g., mosque lamps and Girih tiles ), woodwork and carpets. Secular art also flourished in the Islamic world, although some of its elements were criticized by religious scholars . [3]

Early development of Islamic art was influenced by Roman art , Early Christian art (particularly Byzantine art ), and Sassanian art, with later influences from Central Asian nomadic traditions. Chinese art had a significant influence on Islamic painting, pottery, and textiles. [4] Islamic art was based on Islamic ideals, which were reflected in the art. For example, Minars were constructed to help the Muezzin in spreading the recitation of the Adhan . Islamic art was also represented differently from culture to culture and molded with local traditions. Though the concept of "Islamic art" has been criticised by some modern art historians as an illusory Eurocentric construct, [5] [6] [7]

the similarities between art produced at widely different times and places in the Islamic world, especially in the Islamic Golden Age , have been sufficient to keep the term in wide use by scholars. [8]

Islamic art is often characterized by recurrent motifs, such as the use of geometrical floral or vegetal designs in a repetition known as the arabesque . The arabesque in Islamic art is often used to symbolize the transcendent, indivisible and infinite nature of God. [9] Mistakes in repetitions may be intentionally introduced as a show of humility by artists who believe only God can produce perfection, although this theory is disputed. [10] [11] [12]

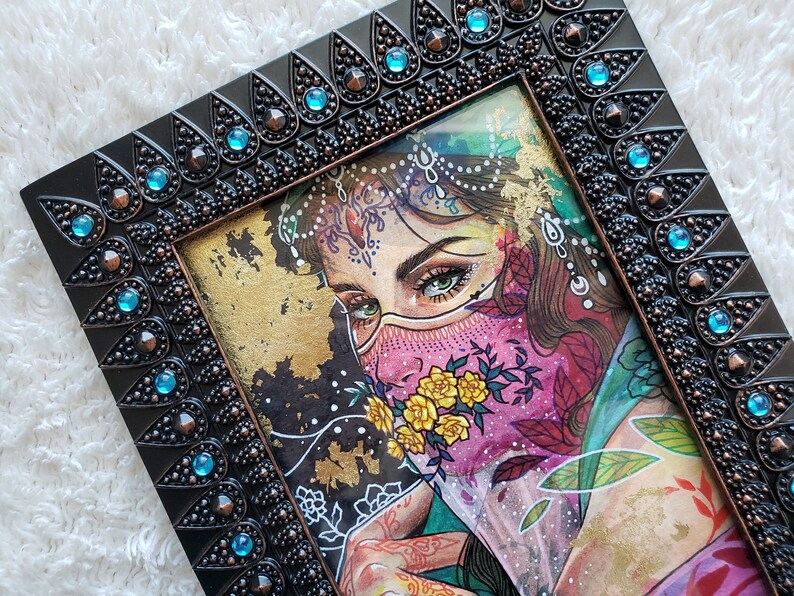

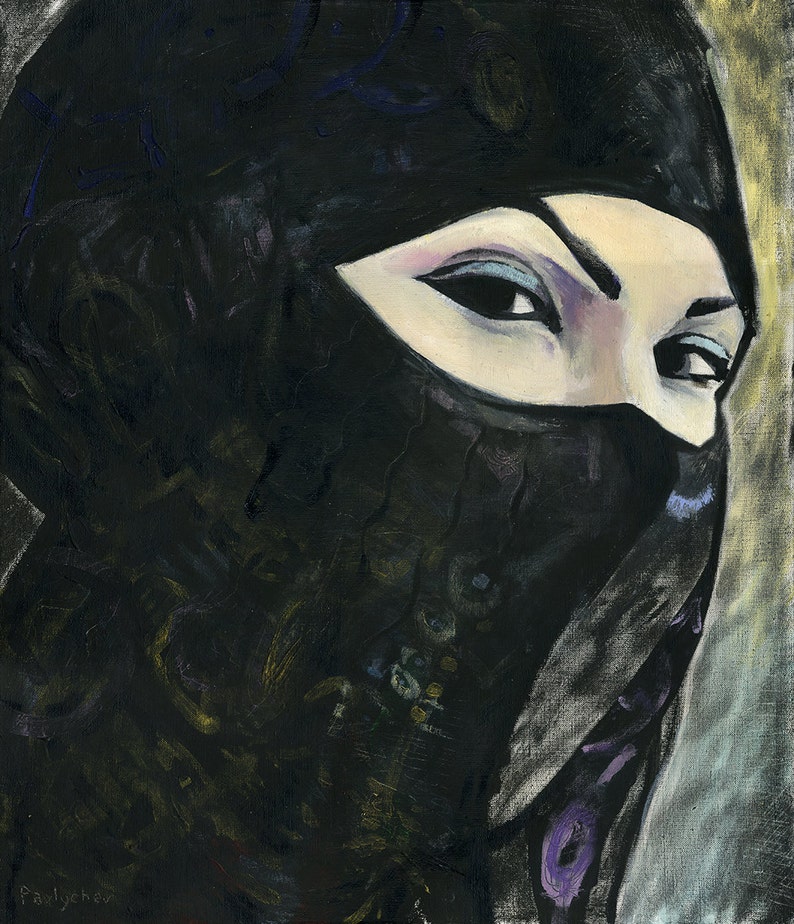

Some interpretations of Islam include a ban of depiction of animate beings, also known as aniconism. Islamic aniconism stems in part from the prohibition of idolatry and in part from the belief that creation of living forms is God's prerogative. [13] [14] Muslims have interpreted these prohibitions in different ways in different times and places. Religious Islamic art has been typically characterized by the absence of figures and extensive use of calligraphic , geometric and abstract floral patterns. However, representations of Islamic religious figures are found in some manuscripts from Ottoman Turkey and Mughal India . These pictures were meant to illustrate the story and not to infringe on the Islamic prohibition of idolatry, but many Muslims regard such images as forbidden. [13] In secular art of the Muslim world, representations of human and animal forms historically flourished in nearly all Islamic cultures, although, partly because of opposing religious sentiments, figures in paintings were often stylized, giving rise to a variety of decorative figural designs. [14]

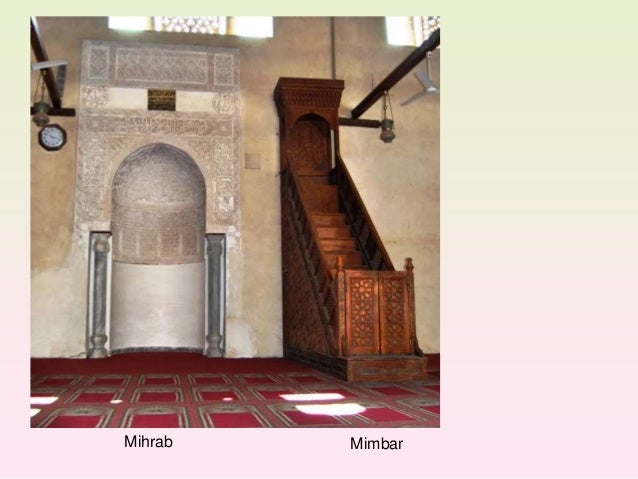

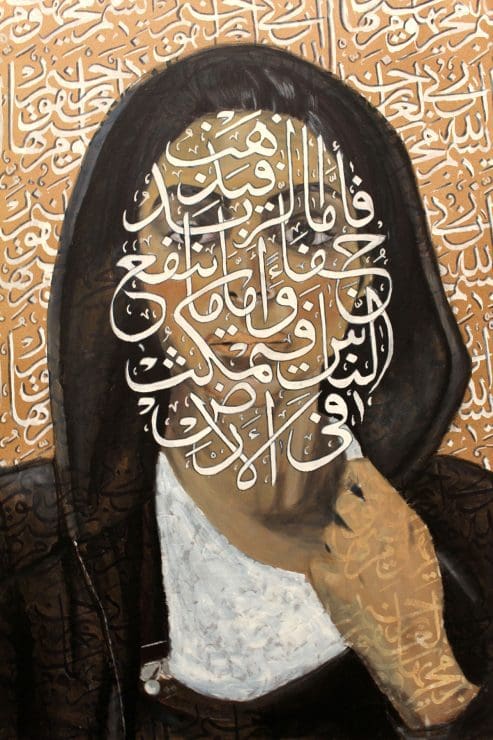

Calligraphic design is omnipresent in Islamic art, where, as in Europe in the Middle Ages , religious exhortations, including Qur'anic verses, may be included in secular objects, especially coins, tiles and metalwork, and most painted miniatures include some script, as do many buildings. Use of Islamic calligraphy in architecture extended significantly outside of Islamic territories; one notable example is the use of Chinese calligraphy of Arabic verses from the Qur'an in the Great Mosque of Xi'an . [15] Other inscriptions include verses of poetry, and inscriptions recording ownership or donation. Two of the main scripts involved are the symbolic kufic and naskh scripts, which can be found adorning and enhancing the visual appeal of the walls and domes of buildings, the sides of minbars , and metalwork. [9] Islamic calligraphy in the form of painting or sculptures are sometimes referred to as quranic art . [16]

East Persian pottery from the 9th to 11th centuries decorated only with highly stylised inscriptions, called "epigraphic ware", has been described as "probably the most refined and sensitive of all Persian pottery". [17] Large inscriptions made from tiles, sometimes with the letters raised in relief , or the background cut away, are found on the interiors and exteriors of many important buildings. Complex carved calligraphy also decorates buildings. For most of the Islamic period the majority of coins only showed lettering, which are often very elegant despite their small size and nature of production. The tughra or monogram of an Ottoman sultan was used extensively on official documents, with very elaborate decoration for important ones. Other single sheets of calligraphy, designed for albums, might contain short poems, Qur'anic verses, or other texts.

The main languages, all using Arabic script , are Arabic , always used for Qur'anic verses, Persian in the Persianate world, especially for poetry, and Turkish , with Urdu appearing in later centuries. Calligraphers usually had a higher status than other artists.

Although there has been a tradition of wall-paintings, especially in the Persianate world, the best-surviving and highest developed form of painting in the Islamic world is the miniature in illuminated manuscripts , or later as a single page for inclusion in a muraqqa or bound album of miniatures and calligraphy . The tradition of the Persian miniature has been dominant since about the 13th century, strongly influencing the Ottoman miniature of Turkey and the Mughal miniature in India. Miniatures were especially an art of the court, and because they were not seen in public, it has been argued that constraints on the depiction of the human figure were much more relaxed, and indeed miniatures often contain great numbers of small figures, and from the 16th century portraits of single ones. Although surviving early examples are now uncommon, human figurative art was a continuous tradition in Islamic lands in secular contexts, notably several of the Umayyad Desert Castles (c. 660-750), and during the Abbasid Caliphate (c. 749–1258). [18]

The largest commissions of illustrated books were usually classics of Persian poetry such as the epic Shahnameh , although the Mughals and Ottomans both produced lavish manuscripts of more recent history with the autobiographies of the Mughal emperors, and more purely military chronicles of Turkish conquests. Portraits of rulers developed in the 16th century, and later in Persia, then becoming very popular. Mughal portraits, normally in profile, are very finely drawn in a realist style, while the best Ottoman ones are vigorously stylized. Album miniatures typically featured picnic scenes, portraits of individuals or (in India especially) animals, or idealized youthful beauties of either sex.

Chinese influences included the early adoption of the vertical format natural to a book, which led to the development of a birds-eye view where a very carefully depicted background of hilly landscape or palace buildings rises up to leave only a small area of sky. The figures are arranged in different planes on the background, with recession (distance from the viewer) indicated by placing more distant figures higher up in the space, but at essentially the same size. The colours, which are often very well preserved, are strongly contrasting, bright and clear. The tradition reached a climax in the 16th and early 17th centuries, but continued until the early 19th century, and has been revived in the 20th.

No Islamic artistic product has become better known outside the Islamic world than the pile carpet, more commonly referred to as the Oriental carpet ( oriental rug ). Their versatility is utilized in everyday Islamic and Muslim life, from floor coverings to architectural enrichment, from cushions to bolsters to bags and sacks of all shapes and sizes, and to religious objects (such as a prayer rug , which would provide a clean place to pray). They have been a major export to other areas since the late Middle Ages, used to cover not only floors but tables, for long a widespread European practice that is now common only in the Netherlands . Carpet weaving is a rich and deeply embedded tradition in Islamic societies, and the practice is seen in large city factories as well as in rural communities and nomadic encampments. In earlier periods, special establishments and workshops were in existence that functioned directly under court patronage. [19]

Very early Islamic carpets, i.e. those before the 16th century, are extremely rare. More have survived in the West and oriental carpets in Renaissance painting from Europe are a major source of information on them, as they were valuable imports that were painted accurately. [20] The most natural and easy designs for a carpet weaver to produce consist of straight lines and edges, and the earliest Islamic carpets to survive or be shown in paintings have geometric designs, or centre on very stylized animals, made up in this way. Since the flowing loops and curves of the arabesque are central to Islamic art, the interaction and tension between these two styles was long a major feature of carpet design.

There are a few survivals of the grand Egyptian 16th century carpets, including one almost as good as new discovered in the attic of the Pitti Palace in Florence, whose complex patterns of octagon roundels and stars, in just a few colours, shimmer before the viewer. [21] Production of this style of carpet began under the Mamluks but continued after the Ottomans conquered Egypt. [22] The other sophisticated tradition was the Persian carpet which reached its peak in the 16th and early 17th century in works like the Ardabil Carpet and Coronation Carpet ; during this century the Ottoman and Mughal courts also began to sponsor the making in their domains of large formal carpets, evidently with the involvement of designers used to the latest court style in the general Persian tradition. These use a design style shared with non-figurative Islamic illumination and other media, often with a large central gul motif, and always with wide and strongly demarcated borders. The grand designs of the workshops patronized by the court spread out to smaller carpets for the merely wealthy and for export, and designs close to those of the 16th and 17th centuries are still produced in large numbers today. The description of older carpets has tended to use the names of carpet-making centres as labels, but often derived from the design rather than any actual evidence that they originated from around that centre. Research has clarified that designs were by no means always restricted to the centre they are traditionally associated with, and the origin of many carpets remains unclear.

As well as the major Persian, Turkish and Arab centres, carpets were also made across Central Asia, in India, and in Spain and the Balkans. Spanish carpets, which sometimes interrupted typical Islamic patterns to include coats of arms , enjoyed high prestige in Europe, being commissioned by royalty and for the Papal Palace, Avignon , and the industry continued after the Reconquista . [23] Armenian carpet -weaving is mentioned by many early sources, and may account for a much larger proportion of East Turkish and Caucasian production than traditionally thought. The Berber carpets of North Africa have a distinct design tradition. Apart from the products of city workshops, in touch with trading networks that might carry the carpets to markets far away, there was also a large and widespread village and nomadic industry producing work that stayed closer to traditional local designs. As well as pile carpets, kelims and other types of flat-weave or embroidered textiles were produced, for use on both floors and walls. Figurative designs, sometimes with large human figures, are very popu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_art

https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/art/art_1.shtml

Old Men Fuck Japanese Mom And Daughter

Niyama Private Island 5 Deluxe

Espn College Basketball Point Spread

Islamic art - Wikipedia

BBC - Religions - Islam: Islamic art

Islamic Art Definition, Paintings, Sculptures Artists and ...

Introduction to Islamic Art - Muslim HeritageMuslim Heritage

Islamic art - the most expensive Arabic paintings

200+ Free Islamic Art & Islam Images - Pixabay

Islamic arts | Characteristics, Calligraphy, Paintings ...

Islamic Art Images, Stock Photos & Vectors | Shutterstock

Muslim Paintings | Fine Art America

Islamic art... - YouTube

Muslim Art