Mikhail Bulgakov against USSR

Ez

There is no political news for me today. These “community work days” are musty, Soviet, slave trash, with a dirty admixture of Jews.”

-Mikhail Bulgakov

The study of anti-Soviet resistance time after time opens new unique pages in the biographies of famous people. We know that hundreds of outstanding Russian writers who went into exile, such as Bunin, Shmelev, Kuprin, openly supported the White Guards, but it is all the more interesting to get acquainted with the articles of writers who remained in sub-Soviet Russia and worked under the supervision of communist censorship. During the years of the Civil War, many of them openly supported the Whites, which once again indicates that the intellectual part of Russian society was strongly anti-Bolshevik.

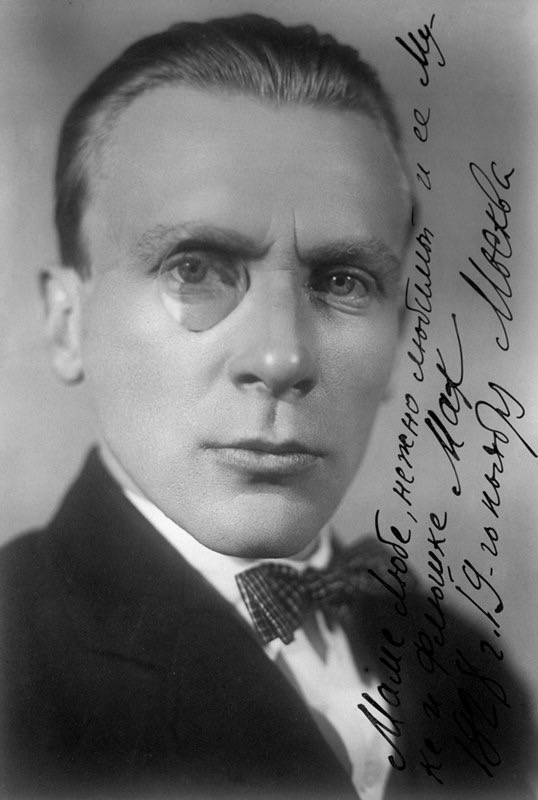

We know Mikhail Bulgakov as the author of the novels "The White Guard", "Heart of a Dog", "The Master and Margarita". All his life he lived and wrote in the USSR.

There is such an episode in his life: in 1919, Bulgakov was mobilized into the Armed Forces of the South of Russia and was appointed military doctor of the 3rd Terek Cossack Regiment. As part of the 3rd Terek Cossack Regiment he was in the North Caucasus. Participated in the famous campaign of General Dratsenko. And Bulgakov served with the Belykhs clearly for ideological reasons and the dictates of his heart - in addition to working as a field doctor, he wrote articles for the Volunteer Army press. Here is one of them:

Michael Bulgakov. "Future Prospects".

Now, when our unfortunate homeland is at the very bottom of the pit of shame and disaster into which the “great social revolution” drove it, many of us are beginning to have the same thought more and more often.

This thought is persistent.

It is dark, gloomy, rises into consciousness and imperiously demands an answer.

It is simple: what will happen to us next?

Its appearance is natural.

We analyzed our recent past. Oh, we have studied almost every point very well over the past two years. Many not only studied it, but also cursed it.

The present is before our eyes. It is such that you want to close your eyes.

Do not see!

What remains is the future. Mysterious, unknown future.

In fact: what will happen to us?..

Recently I had to look through several copies of an English illustrated magazine.

For a long time I looked, enchanted, at the wonderfully executed photographs.

And then I thought for a long, long time...

Yes, the picture is clear!

Colossal machines in colossal factories feverishly day after day, devouring coal, rattling, knocking, pouring streams of molten metal, forging, repairing, building...

They are forging the power of the world, replacing those machines that, until recently, by sowing death and destroying, forged the power of victory.

In the West, the great war of great nations has ended. Now they are licking their wounds.

Of course they will get better, they will get better very soon!

And to everyone whose mind has finally cleared up, to everyone who does not believe the pathetic nonsense that our evil disease will spread to the West and strike it, the powerful rise of the titanic work of peace will become clear, which will lift the Western countries to an unprecedented height of peaceful power.

And we?

We are going to be late...

We will be so much late that none of the modern prophets will probably say when we will finally catch up with them and whether we will catch up with them at all?

Because we are punished.

It is unthinkable for us to create now. We have a difficult task before us - to conquer, to take away our own land.

The reckoning has begun.

Volunteer heroes are tearing Russian land inch by inch from Trotsky’s hands.

And everyone, everyone - both they, fearlessly doing their duty, and those who are now huddling around the rear cities of the south, in the bitter delusion of believing that the matter of saving the country will be accomplished without them, are all passionately waiting for the liberation of the country.

And she will be released.

For there is no country that does not have heroes, and it is criminal to think that the homeland has died.

But you will have to fight a lot, shed a lot of blood, because while the madmen fooled by him are still trampling behind the sinister figure of Trotsky with weapons in their hands, there will be no life, but there will be a mortal struggle.

We need to fight.

And while there, in the West, the machines of creation will be knocking, in our country machine guns will be knocking from one end to the other.

The madness of the last two years has pushed us down a terrible path, and we have no stop, no respite. We have begun to drink the cup of punishment and will drink it to the end.

There, in the West, countless electric lights will sparkle, pilots will drill into the conquered air, there they will build, explore, print, study...

And we... We will fight.

For there is no power that can change this.

We will conquer our own capitals.

And we will conquer them.

The British, remembering how we covered the fields with bloody dew, beat Germany, dragging it away from Paris, will lend us more greatcoats and boots so that we can quickly get to Moscow. And we will get there.

Scoundrels and madmen will be expelled, scattered, destroyed.

And the war will end.

Then the country, bloodied and destroyed, will begin to rise... Slowly,

it's hard to get up.

Those who complain about being “tired” will, unfortunately, be disappointed. Because they will have to be “tired” even more...

It will be necessary to pay for the past with incredible labor, severe poverty

life. Pay both figuratively and literally.

To pay for the madness of the March days, for the madness of the October days, for independent traitors, for the corruption of the workers, for Brest, for the insane use of the money printing machine... for everything!

And we will pay.

And only when it is already very late, we will again begin to create something in order to become full-fledged, so that we will be allowed back into the Versailles halls.

Who will see these bright days?

We?

Oh no! Our children, perhaps, and perhaps our grandchildren, because the scope of history is wide and it can “read” decades just as easily as individual years.

And we, representatives of the unlucky generation, dying in the rank of miserable bankrupts, will be forced to say to our children:

- Pay, pay honestly and always remember the social revolution!

Newspaper "Grozny", November 13, 1919

Such words can only be written by completely dedicating oneself to the cause of the White struggle, realizing the full criminality of Bolshevism. During the retreat of the Volunteer Army at the beginning of 1920, Bulgakov fell ill with typhus and because of this he was unable to leave for Georgia, remaining in Vladikavkaz. At the end of September 1921, he moved to Moscow and here appears that Bulgakov, a Soviet writer whom everyone knows. But who knows how alive the dream was that one day the Whites, about whom he wrote “WE,” would reach Moscow so that the Red scoundrels and madmen entrenched in the ancient Kremlin would be “expelled, scattered, destroyed.” So that historical Russia can be revived. So that people like Bulgakov, who remained in an enslaved country but went into internal emigration, could live freely and create not for the sake of survival, but for the glory of their native land. How many of them were there, forced to write odes to the bloody tyrant Dzhugashvili, but in their souls they kept hope for the liberation of the Fatherland?..

Blood issues are the most difficult issues in the world..."

— M. A. Bulgakov - “The Master and Margarita.”

Bulgakov did not completely personalize the specific heroes of his works. A writer with a great literary gift has no need at all to place emphasis on the author’s text with his own hands. What did Bulgakov do, as all the great satirists did before him, starting with Aristophanes? It was enough for them to show the gap between “one” and “the other,” for example, between the types of people: the Russians Preobrazhensky, Bormenthal, Zinaida and the Bolsheviks of known Middle Eastern origin along with the slow-witted common people. And it’s not for nothing that Dickens was Mikhail’s favorite foreign writer.

Bulgakov really has a lot in common with Preobrazhensky: both of them are doctors, both have a “world name”, both are persecuted by the Bolsheviks, but the most interesting thing is that both have identical origins. Discussing the consequences of the alleged “murder” of Sharikov in a conversation with Bormenthal, Preobrazhensky mentions that his heredity is “even worse” than that of his assistant: his father was a priest, like Bulgakov’s father. Of course, such a pedigree in a country of triumphant manic atheism is comparable in the severity of its burden almost to the imperial family. But for Bulgakov, heredity is something more fundamental, much more significant than the self-determination of characters in literature. And that's why. Firstly, being a doctor, Bulgakov was well versed in biology and knew about eugenics. Secondly, he understood the priestly function of his father’s class, and on this basis he considered himself a full-fledged aristocrat, although he did not belong to the family nobility, but to the personal, that is, acquired. It cannot be said that this “fictitious nobility” was a burden to Bulgakov himself; however, it could not play into his hands either in dealing with the “ancestral nobles” who remained in the USSR (those who had not yet been shot or demonstrably released), much less with the Bolsheviks. And finally, “origin” is an important marker of Bulgakov’s life and work in the Soviet Union. But more on that later.

As for Stalin and his place in Bulgakov’s life, a few words should also be said about this. As a creative person, Bulgakov was burdened by the total lack of culture triumphing around him, the farce of everything party and plebeian in the cultural life of the country. Bulgakov had been a member of the literary circle of Moscow writers since the days of the editorial office of the magazine “Gudok”, but all these people were no equal to Bulgakov; he was simply bored with them. They discussed things that were on completely different value planes from Bulgakov’s world. If Bulgakov’s world is “Faust” and Dostoevsky, or at least Dickens, then it is not difficult to understand what could have interested everyone else there (for example, Kataev’s reasoning about how to get rich or a game of billiards, in which Mayakovsky beat Bulgakov over and over again In its essence, it was an elite of ordinary people). And Bulgakov knew about a certain interest in Stalin’s art, he heard that he watched his play “Days of the Turbins” about fifteen times. At the same time, Bulgakov was a completely frivolous person, in some ways even naive (only such a person could keep the diary that buried him on a bookshelf in plain sight), and besides, Bulgakov was not very good at understanding people, namely in those aspects human qualities that go beyond the “physiological” and move into the area of “personal”, “everyday”. For example, in “The Master and Margarita” Bulgakov made the main informer the screenwriter Sergei Ermolinsky in the image of Aloysius Mogarych, who remained a supporter and friend of Bulgakov to the end, and who, because of his friendship with Bulgakov, was already sent to prison and camps in the 40s . And in a similar naivety, Bulgakov believed that in Stalin he had found “an equal interlocutor” when he called him two days after Mayakovsky’s suicide. But Stalin was interested in Bulgakov only as a political figure working in the USSR for the regime, and Bulgakov, dreaming that Dzhugashvili had at least some human qualities, tried to gain leniency and obtain official permission to travel abroad.

And yet Bulgakov was not stupid, as it might seem at least for a moment to the reader. There is one character in his work, about whom the time will come later, and who very well characterizes Bulgakov himself in everyday life.

Bulgakov, having experienced a period of suicidal stress, after a call from Stalin, received a position as a screenwriter in the theater, which not only saved the writer from a difficult situation, but also gave him a free hand in independent creativity. That is, his works were still criticized to pieces by the press, and his plays were banned by Soviet censorship only because the author was named Bulgakov. Here's an example: Bulgakov wrote a play about Moliere, “The Cabal of the Holy One,” which tells about the tragedy of the writer during the period of monarchical tyranny (that’s what it looks like at first glance). Politically, the play corresponds to left-wing discourse, but due to the fact that Bulgakov wrote it, it was immediately banned by the Committee for Cultural Affairs. Then Stalin allows it, but when the play is successfully staged several times, the chairman of the Committee on Arts Platon Kerzhentsev writes a report to Stalin and Molotov, in which he “exposes Bulgakov’s secret political plan” - to draw an analogy between the tyranny of the French monarch and the dictatorship of the proletariat, and the play is again banned . Absurd? Without a doubt. But now it’s Bulgakov’s turn to laugh at reality. Since absolutely all of Bulgakov’s plays were banned from production, he mockingly wrote “Batum,” a play about Stalin’s youth. It is not difficult to guess what her future fate was when the committee saw the hated name behind the author.

This is a first-class mocking move, like a blow in response with a weapon taken from the enemy. In those days in the USSR, only Bulgakov could do this, and this is one of the characteristics of the genius of his literary talent and personality. Bulgakov was absolutely unclear, completely alien to everything vulgar, “Soviet”, “socialist”. Now one can only regret that Bulgakov was never able to leave the USSR, which oppressed the writer within the creative framework. If Bulgakov had worked in Europe or free Russia, he would have been spoken of not as a Russian Dickens, but as a new Dostoevsky or Goethe.

However, Bulgakov himself still believed that escape was still possible.

We can say that all three times Bulgakov was happily married. Of course, to the degree of happiness to which an unhappy person can be found in his essence. His first wife, Tatyana Lappa, who came from a hereditary noble family, not only characterizes the stage of the Bulgakovs’ life in pre-revolutionary Russia, but also the marriage of two noble people in the Russian Empire in principle. When the First World War began, she went to the front with Bulgakov as a sister of mercy, she saved the writer from addiction to morphine (secretly reduced the dose to zero), was with her husband during the civil war, treated him for typhus in Vladikavkaz, together they survived their the hungriest year in Moscow. But the marriage of Bulgakov and Lappa could not continue in their new world, primarily for the reason that in its mental essence, the Soviet Union was the antipode of everything noble, the biological enemy of the aristocratic Beginning. When they separated in 1924, Bulgakov asked Lappa not to tell anyone what she knew about him.

Tatyana Lappa, of course, kept her word. Largely thanks to this loyalty (and mutual, despite the separation, they still loved each other) Bulgakov lived until 1940. What did Lappa know and what should have remained secret? First of all, Bulgakov’s worldview. In this sense, the novel “The White Guard” serves as the most valuable autobiographical source of Bulgakov’s world. It is well known that the Turbin family and their friends (that is, all the main characters of the novel) have their real prototypes from the acquaintances, friends and relatives of Bulgakov himself, who experienced those events in Kyiv with him. For example, the writer’s closest friend, Nikolai Syngaevsky, in the novel Lieutenant Myshlaevsky, speaks on behalf of his friends: “Only one thing is possible in Rus': the Orthodox faith, the power of the Tsar!”, thereby denoting a common marker of the White Guard ideology of Bulgakov’s heroes and the author himself.

The most antagonistic character in The White Guard is Captain Talberg, the husband of Elena Talberg-Turbina, whose image is completely copied from Leonid Karum, the husband of Bulgakov’s sister, whom Bulgakov himself hated. A cowardly careerist, he leaves his wife and leaves by emergency train on an embassy mission to Germany, leaving the heroes of the novel (that is, Bulgakov and his friends) to their deaths. In reality, everything was much simpler and much more vile: Karum was one of the first who betrayed the military oath to Russia and went over to the side of the Bolsheviks in Kyiv.

- “In March 1917, Talberg was the first - understand, the first - who came to the military school with a wide red bandage on his sleeve...”

After the publication of The White Guard, Bulgakov even quarreled with his sister over her husband, and it is obvious that this conflict was primarily an ideological conflict: Bulgakov never betrayed Russia, and Karum was one of the first to do so...

The clear opposite of the scoundrel Talberg is the heroic Colonel Nai-Tours, who has become the collective image of the Russian White officer. Nai-Tours speaks with a clear accent, it may seem that Lavr Kornilov or someone else with Eastern origin was taken as his basis, but in fact, his image is revealed to the reader through the transcription of this mysterious name. Nai-Tours is nothing more than a derivative of the English Knight (Knight) and the Latin Urs (Bear), that is, Knight-Bear. Thus, the etymology of his name speaks of a purely military archetype, characteristic of the Nordic sagas and heroic myths of Antiquity. Therefore, Count Fyodor Keller, with whom Bulgakov might have been familiar, is often considered to be the prototype of Nai-Tours. Then it becomes clear why Nai-Tours speaks with an accent characteristic of Germans in Russian service. Nai-Tours is not only the most heroic character in Bulgakov’s entire work, but, thus, also the most “White Guard”, the most military and the most ur-fascist, for whom the writer himself has the deepest respect and honor.

All this, as well as many other facts that Tatyana Lappa faithfully kept with herself as a secret until the end of her life, obviously speak not only about monarchical, but above all about traditionalism in Bulgakov’s worldview (of course, not in the context of the teachings of Rene Guenon, but in its general conceptual form). And although Bulgakov himself was not religious, it is also obvious that he believed in the necessity of Faith for Russia in the same order of political structure, characteristic of all traditionalists.

There is nothing special to say about his second wife, Lyubov Belozerskaya, except that she, like Lappa, came from a noble family, but at the same time came to the USSR from emigration and served as the prototype for Margarita from The Master and Margarita, despite the fact that that Elena Shilovskaya, the writer’s third wife, after Bulgakov’s death, defended the thesis that Margarita was her.

Elena Shilovskaya herself, born Nuremberg in the family of a baptized Jew, was for Bulgakov, as it seemed to him, the last lifeline in the whirlpool of destinies of his life. Actually, marriage with a representative of a certain nationality that seized power in Russia was for a Russian nobleman at least some kind of (often very strong) guarantor of “loyalty” to the Soviet regime and the subsequent preservation of his own life. An indicative moment: her ex-husband, General Shilovsky, only thanks to his marriage to her was not shot when he should have received a bullet in the dungeons of the NKVD (1929, 1937).

In 1932, Bulgakov married Shilovskaya. He understood that only in this way, having proven his loyalty to the ruling class, would he be able to get exit from the USSR through the writer's line. But Bulgakov was not Zamyatin, who was loyal to the left fundamentally and ideologically even before the revolution, and who was given the go-ahead to leave already in the post-NEP Iron Curtain years. He remained until the end of his life “White Guard Bulgakov,” a captive of the Soviet Union and the literary property of communist cannibalism, and the Bolsheviks themselves, who built an empire of lies and denunciations, perfectly felt this trickery of Bulgakov - a promise to be, like Zamyatin, loyal to the USSR, but to leave. Several times after his marriage to Shilovskaya, he applied for a foreign visa, but was always refused (often at the last moment). And then Bulgakov died. It is believed that he died, like his father, from kidney failure. He was diagnosed with “hypertensive nephrosclerosis” on September 15, 1939, and six months later, on March 10, 1940, Bulgakov died. Then there was an autopsy, which Shilovskaya refers to in her memoirs, but there are no documents about the autopsy themselves, and Bulgakov’s body was cremated.

It’s incredible how Bulgakov lived for 29 years in a country in which he should have been shot back in the 20s. A few people like Bulgakov, already in the 30s, were long-livers for Soviet realities, and for 1939 they were generally living dead. Before his death, Bulgakov said: “As you know, there is one decent type of death - from a firearm, but, unfortunately, I don’t have one.”

There is every reason to believe that the Bolsheviks killed Bulgakov during the well-known foreign policy processes in Europe. Bulgakov himself was an excellent doctor and throughout his treatment he noted that he was treated in an extremely strange way. In other words, there was no treatment at all. So, for example, M. S. Vovsi (one of the defendants in the “Trial of Doctors” in the future) predicted Bulgakov’s death in three days and suggested that the writer die in a Kremlin hospital. Bulgakov refused and lived for several months. Moreover, Bulgakov, like the underground millionaire Koreiko, carefully monitored his health and was examined almost every year, and he did not have any pathologies. It is most likely that Bulgakov's kidney disease arose as a side effect of the use of low-grade antidepressants and headache medications that tormented Bulgakov in the 30s. One way or another, when the writer fell ill, the Bolsheviks did everything possible to ensure that the disease “finished” him.

Bulgakov is believed to have fallen ill on August 14, 1939. But the first attacks, from his memories, began only in September, which leads to certain thoughts. The chain of subsequent historical events looks like this:

On August 19, Bulgakov begins to learn Italian (Mikhail Afanasyevich himself was a polyglot and spoke about six foreign languages).

August 23, 1939 – Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

September 1, 1939 – the beginning of hostilities in Europe.

September 17 – USSR troops enter Poland.

On October 14, Bulgakov issues a power of attorney to conduct business in his wife’s name and also registers a will.

November 30, 1939 – the beginning of the war between the USSR and Finland.

December 14, 1939 – expulsion of the USSR from the League of Nations.

In February 1940, at the request of Fadeev, A. A. Bulgakov was allowed to go to Italy for treatment (!).

March 10, 1940 Bulgakov dies.

If we today, having proper knowledge of racial theory and understanding the psychology of the masses and classes, ask ourselves the question: “Why was Bulgakov persecuted by the Bolsheviks?” - we will come to an answer that is extremely fundamental for us: this was a man who could buy a monocle as a joke and be photographed in it, turning out to be so natural for himself and that general biological collective type that forms the aristocratic class in Europe, thereby giving the photograph itself a lasting feeling the fact that the photograph itself simply could not have been taken in Soviet Russia, that it depicts not a Soviet citizen, but a family Prussian aristocrat (where the fashion for monocles came from in the 19th century). This was a man from another world, who was surrounded by annoying critics, “poets of the revolution”, journalists, would-be writers, outright scatterers of papers, such as Kataev, Ilf and Petrov, Olesha, and the like. He was perceived by this mass with ressentimental hatred for the figure, photographed in the authentic form of an aristocrat with a monocle, that is, in front of them was a real master as an enemy, not only a class enemy, but above all a biological enemy. And because of this, the entire mob surrounding him fell into a frenzy.

So, from the moment he began studying Italian and Bulgakov’s desire to leave for fascist Italy until the fictitious approval of an exit visa, and then his imminent death. But could Bulgakov leave? - Rather, it is correct to ask another question: could Bulgakov even survive?

The great Russian writer Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov occupies a special place in the literary pantheon for Russian fascists and heirs of the White Guard idea. He is not only the very last great Russian writer, whose literary heritage and personality should be subjected to careful revisionism (also undertaken by our editors for our readers), but also a colossal, above all in his absolute tragedy, example of how “good” really is. life of a noble Russian man under Soviet rule.

Eternal memory to Mikhail Bulgakov.