Dark Ages in Agony (promotional excerpt)

Ignat Solovey (translation); text by Sergei Zotov, Mikhail Maizuls, Dilshat HarmanPassions of Middle Ages: (not so) sacred images

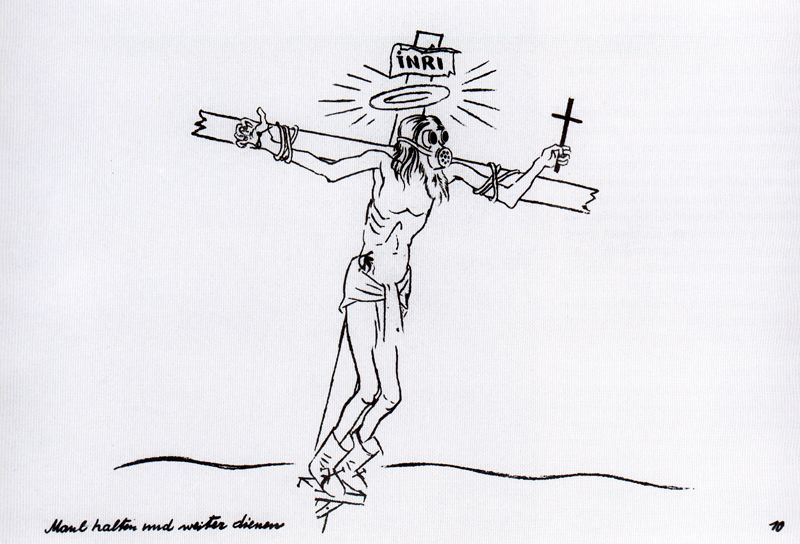

A cross. A loinclothed man nailed to it, halo shining over his head. Above is the plate that reads INRI: “Jesus of Nazareth, King of Jews”. A regular crucifix, apart from boots that Jesus wears and a gas mask covering his face. This sketch was drawn by German expressionist Georg Gross in 1927 for a setting of “The Good Soldier Švejk”, an anti-war play staged in one of Berlin theaters (based on the famous novel by Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek).

Soon afterwards “Jesus in a Gas Mask” was published in a separate book together with other Gross's sketches. Gross and the publisher were convicted according to Article 166 of Wiemar Republic Penal Code for “insult of religion”. For a blasphemy, as such.

Gross lost the first suit, being acknowledged guilty in denigration of Christ and Church. The artist and the publisher were each sentenced to either to spend two months in jail or pay a 2000 Mark fine. The prosecution that deemed three pictures blasphemous was outraged with iconographic frivolity of the crucifix meaning boots and gas mask, but the key concern was the writing in the bottom left corner: Maul halten und weiter dienen — “Shut up and follow the orders”.

Who said that and to whom? The prosecution stated that the artist's intent was to make Christ utter that ruthless command. Gross retorted that, quite contrary, the words were addressed to Christ who depicted the humanity crucified by war. That was what would Jesus hear if he came to trenches of the Great War preaching love and peace. The court agreed to the party of charge and ruled that Christ, from Gross's standpoint, offers people nothing but a cynical slogan.

Yet, in 1929 a superior court sustained the artist's appeal and ruled the following: preaching war in a church is as incompatible with ecclesial doctrine as gas mask and boots are incompatible with an image of Christ, so the artist wanted to show that those who preach war rejected Christ. Still, both Catholic and Lutheran clergy continued to attack Gross and the prosecution kept pushing. After much drudgery, the case reached the Supreme Court in 1931. While being unable to prove the artist and his publisher guilty, the Supreme Court ruled to confiscate and destroy all printed copies of the pictures. Gross had to leave Germany on January of 1933, shortly before Adolf Hitler became the Chancellor, not in the least because Nazis long labeled him bolshevik and an enemy of Fatherland. [...]

Eternity in the Present

A gas mask drawn by Gross in his version of crucifix seemed scandalous not only because it concealed Christ's face and effectively depersonalized him. It was the very item: a gas mask was annoyingly modern and earthbound. Had Gross, say, veiled the God-man with an aer, like it was done on many medieval depictions of the Mocking of Christ, hardly anyone would feel that hurt.

From conservative standpoint, evangelical subjects transferred to the present with modern artifacts in the picture often look sacrilegious by themselves, and it is absolutely unnecessary for an image to be satirical to cause an outrage. The scandalized ones think that an artist who depicts Jesus and apostles wearing suits or, say, jeans and tee shirts instead of ancient chitons, disperses the sacred glory. Paradoxically, modernization is often used to restore the emotional power of ancient concepts and to help a viewer to identify with them.

While it may seem that such “adjustment” of the past to the present is a recent invention, it is not so. Since the time when medieval iconography started to distance itself from pure symbolism (it happened in the 12th–13th centuries) and paid more attention to reality like clothes, interiors and architecture, such technique became ubiquitous. The episodes of Scripture were simultaneously perceived both as something from a distant past (Egypt of Moses and Palestine of Christ) and as a source of timeless verity, a key to each and everyone's salvation and a matrix of myriad of other events that happen here and now. Saints murdered for their beliefs repeated the Epichristian martyrdom, sinners crucified Jesus again and again with their crimes... This perpetually living past was often depicted in (seemingly) contemporary setting.[...]

Even if medieval artists and their clerical “consultants” knew what Jerusalem looked like in the 1st century A.D., and what did Jewish fishermen and Roman warriors wear then (neither, of course had a way to know that), such information would hardly add documentary precision in a modern sense. In a whole, the High Middle Ages were interested neither in archeology or ethnography of the past, nor in the changes of material world built by people. Chronologists and theologians, of course, saw the upheavals of history and divided it into two eras (before and after Christ), or into six “periods” (Adam to Noah, Noah to Abraham, Abraham to David, etc.) or into three “ages” (“before the Law”, “the Age of Law”, “the Age of Holy Grace”). Still, that concerned Divine Providence and the key points of the Salvation history. Changes in customs, mores, clothing, architectural styles and other elements of material world were of no consequence.[...]

By their illustrations of Scripture medieval artists tried to uncover the timeless sense of evangelical stories, to show their perpetual modernity, i.e. that the eternal past is always here and passes through each person's destiny. If an artist from, say, 13th century Paris had to draw the Pharaoh's army pursuing Moses, or Philistines fighting Israelis, or King Herod's warriors during the Massacre of the Innocents, he would probably draw them wearing armor suits common for France of his time. Shields of ancient Israelis and their enemies, and even the early Christian warriors like St. George or St. Mauritius and their foes, often bore coats of arms. The whole idea of a coat of arms emerged only in the 12th century A.D.

Such anachronisms were common not only when it came to the episodes of Sacred History. Ancient Greeks fighting Trojans, or Romans during the Carthage campaign were depicted as medieval knights as well. Ancient foes of Christ were often shown as contemporary foes of Christianity, most commonly Mohammedans. Such double-edged approach (it simultaneously demonized gentiles and related them to the Savior's extortioners, and affirmed the hatred to the latter correlating them to the former) nicely survived till the early modern period. For example, in Venetian paintings of the 16th century (like Tintoretto's) the pursuers of Christ and first martyrs are regularly depicted as Ottomans wearing colorful robes and turbans. The present and the past, the common and the exotic were intertwined to strengthen the ideological and emotional message of images.

Medieval artist would never say that recent fashions and technical advancements have no place in scriptural subjects. Since the 14th century Saint Jerome of Stridonium (Christian erudite and ascetic hermit who lived in 300–400s A.D. and later was proclaimed one of the Church Fathers) was depicted wearing cardinal's dress, a long crimson robe and matching wide-brimmed hat, to emphasize his high position. At that, there were no cardinals in St. Jerome's times. Such attire appeared only in the same 14th century and was brought to the distant past by imagination.

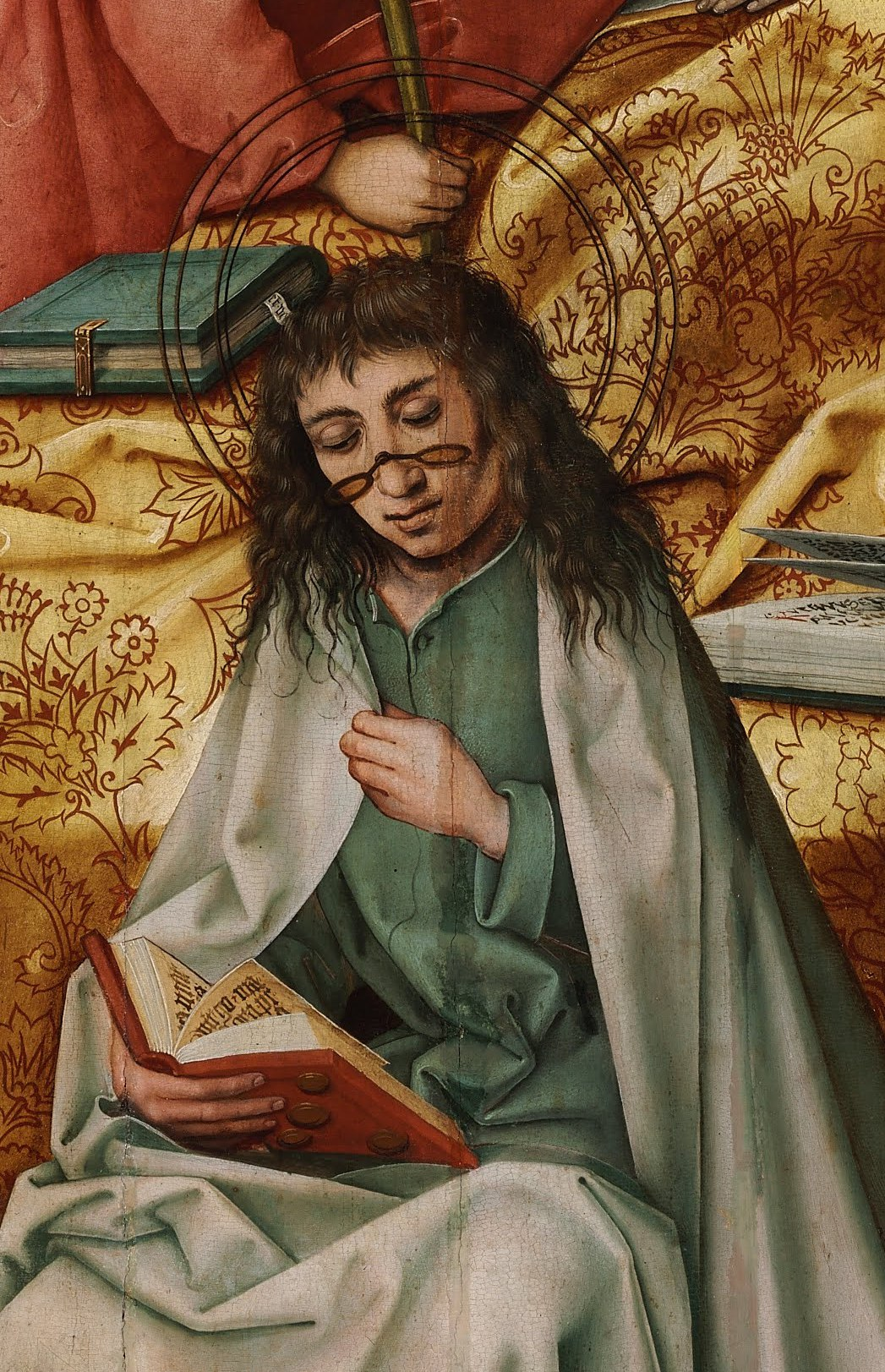

Roughly at the same time the Church Fathers, evangelists and other saints who were partial to studies, started to be depicted wearing spectacles. A prized accessory that allowed intellectuals who lost the vision acuity to continue their works, was invented in Italy in the late 1200s and spread across Europe. As a result, eyeglasses were considered an attribute of lore and book culture, and were introduced into iconography of evangelists and theologians — the Christian masters of word. Later, though, eyeglasses obtained negative connotations and became synonymous to spiritual blindness of sinners and, at times, demons themselves. Yet, at least initially, the artists who painted ancient saints bespectacled definitely knew how recent the invention was.

In the art of the 15th century Netherlands many scriptural events were transplanted into contemporary spaces and interiors that were depicted with the utmost precision. A room where Archangel Gabriel pronounces the Glad Tidings to the Virgin often resembles chambers of a wealthy aristocrat or a burgeois who ordered the painting. Benches with pillows, window blinds, fireplaces, candlesticks, pots, painted engravings of saints (a novelty of the period) and tiled roofs seen outside...

Of course these Flemish Biblical interiors cannot be considered precise depictions of real interiors, nor “portraits” of real rooms. Many items, however common they may seem, had metaphorical meaning and were, as renowned art historian Erwin Panofsky dubbed them, “hidden symbols”. A lily placed in a vase standing somewhere on a table or on the floor meant the purity of Holy Mother; a candlestick with a candle referred to Mary and her divine Baby, etc.

In such scenes contemporary interiors contain theological symbols and details that clearly make the events happen not in the 15th century Netherlands. For example, in a scene of the Last Supper a table could look like the one a viewer had at home. Yet, in strict accordance to the Scripture (Matthew 10:10) the Disciples were painted barefoot, which would be unlikely practice at feasts in Gent or Bruges. Nevertheless such images, where symbols assumed contemporary shapes, created powerful impressions that the events are unfolded here and now or at least in a world very similar to those of a viewer.

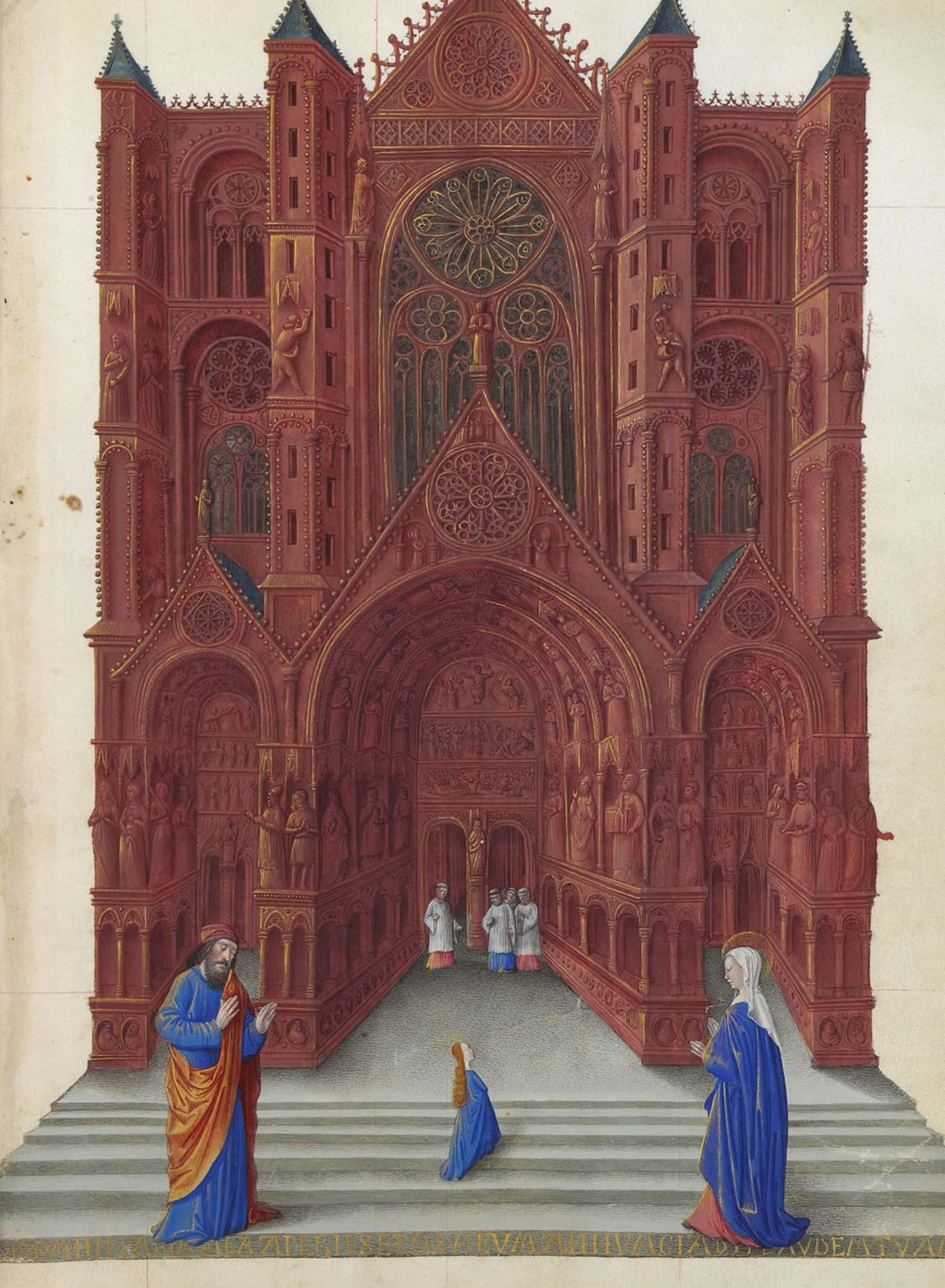

The same can be said of cityscapes. Many Italian, Dutch, French and German artists of the Late Middle Ages painted Jerusalem of Old and New Testament as European cities familiar to them (and their customers). Or, otherwise, imagined their cities as Jerusalem, transferring the familiar spikes and towers into sacred space of Nativity or Crucifixion. In Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry created by Limbourg brothers in 1411–1416, The Magi assemble for the journey to present their gifts to baby Jesus in a Gothic city that is easily recognized as Paris, with its Notre-Dame and Saint Chapelle. In a miniature that was added to that book in the late 1400s, the Temple of Jerusalem (where parents brought young Mary, the future mother of the Savior) looks like a Gothic building strikingly similar to St. Stephan's Cathedral in Bourges.

The signs of present (Gothic spires, knight armor, coats of arms...) neighbored some archaic (like chitons of Antiquity) or oriental (like turbans on the heads of Christ's tormentors) details in the same picture. Present and sacred past joined each other, but did not mix. If we alter many late medieval pictures to make them contemporary to us, we would see the Way to Calvary in front of La Defense in Paris, Guggenheim museum or Manhattan skyline; Roman soldiers in medieval armor with two-way portable radios; Jesus in a chiton being filmed with smartphones by crowd from behind police lines.